Racism

Racism is an ideology according to which people are categorized and judged as a "race" on the basis of external characteristics - which suggest a certain ancestry. The characteristics used for differentiation, such as skin colour, body size or language - sometimes also cultural characteristics such as clothing or customs - are interpreted as a fundamental and determining factor of human abilities and characteristics and are classified according to value. In doing so, racists usually regard people who are as similar as possible to their own characteristics as having higher value, while all others are discriminated against (often on a graded basis) as having lower value. Such outdated racial theories were and are used to justify various actions that contradict today's general human rights.

The term racism emerged at the beginning of the 20th century in the critical examination of political concepts based on racial theories. In anthropological theories about the connection between culture and racial characteristics, the concept of race was mixed with the ethnological-sociological concept of "people", e.g. by the völkisch movement. In this context, racism does not target subjectively perceived characteristics of a group, but questions their equal status and, in extreme cases, their right to exist. Racist discrimination typically attempts to refer to projected phenotypical differences and personal differences derived from them.

Regardless of their origin, everyone can be affected by racism. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination does not distinguish between racial and ethnic discrimination. An expanded concept of racism can also include a variety of other categories. People with racial prejudices discriminate against others on the basis of such affiliations; institutional racism denies benefits and services to certain groups or privileges others. Racist theories and patterns of argument serve to justify relations of domination and to mobilize people for political goals. The consequences of racism range from prejudice and discrimination to racial segregation, slavery, pogroms, so-called "ethnic cleansing" and genocide.

Biologically, a subdivision of the recent species Homo sapiens into "races" or subspecies cannot be justified. In order to investigate certain geographically divergent human characteristics, human biology instead delimits individual populations, which are only related to the characteristic under investigation or are made arbitrarily in advance. Even if insights into the descent history of humans are gained from this and the layperson believes to recognize apparent similarities to racial concepts, they are neither suitable for taxonomic purposes nor do they substantiate the biosystematic subdivision of humans into subgroups.

The concept of racism overlaps with that of xenophobia and can often be distinguished from it only imprecisely. Parts of social science distinguish between xenophobia and racism.

Play media file Video: When did racism start?

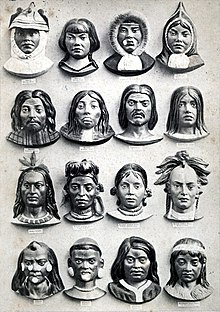

A systematic division of people into races, typical for the 19th century (after Karl Ernst von Baer, 1862).

General

Racism, in the strict sense of the word, explains social phenomena by means of pseudo-scientific analogies from biology. As a reaction to the egalitarian claims to universality of the Enlightenment, it attempts a seemingly inviolable justification of social inequality by reference to scientific findings. Culture, social status, aptitude and character, behavior, etc. are considered to be determined by hereditary-biological endowment. A supposedly natural or God-given, hierarchical-authoritarian order of rule and the constraints on action that follow from it serve to justify discrimination, exclusion, oppression, persecution or annihilation of individuals and groups - both on an individual and institutional level. Differences in skin colour, language, religion and culture stabilise the demarcation between the various groups and are intended to secure the primacy of one's own over the foreign. The civilisational progress of modernity is interpreted as decadent, contradicting a natural inequality of people.

The historian Imanuel Geiss sees in the historical foundations of the Indian caste system the "oldest form of quasi-racist structures". According to Geiss, they took their beginning at the latest with the conquest of North India by the Aryans around 1500 BC; "light-skinned conquerors pressed subjugated dark-skinned people as 'slaves' into the apartheid of a racial-caste society, which could not be maintained in the original form in the long run, but led to the extreme fragmentation and segregation of the castes as insurmountable communities of life, occupation, living, eating and marriage" (ibid.). In ancient Greece, the barbarians were not regarded as "racially inferior", but "only" as culturally or civilisationally retarded, but here, too, some historians speak of prototypical or "proto-racism".

"Modern" racism emerged in the 14th and 15th centuries and was originally based more on religion (Fredrickson, p. 14). Beginning in 1492, after the Reconquista, the reconquest of Andalusia by the Spanish, Jews and Muslims were persecuted and expelled from Spain as "foreign invaders" or simply as "marranos" (pigs). While the formal option of (more or less voluntary) baptism existed to escape expulsion or death, it was assumed or implied that conversos (converted Jews) or moriscos (converted Moors) continued to practice their faith in secret, effectively depriving converts of the opportunity to become full members of society. The "Jewish" or the "Islamic", but also the "Christian", was declared to be the inner being, the "essence" of man, and religious affiliation thus became an insurmountable barrier. The idea that baptism or conversion was not enough to erase the taint essentialized or naturalized religion and is therefore considered by many historians to be the birth of modern racism. The notion that a Jew or Muslim retains his Jewish or Muslim "essence" even after he has changed his religion - that it is in his blood, so to speak - is racist at its core. "The old European belief that children have the same 'blood' as their parents was a metaphor and a myth rather than an empirical scientific finding, but it sanctioned a kind of genealogical determinism that turns into racism when applied to whole ethnic groups" (Fredrickson, p. 15). The Estatutos de limpieza de sangre ("Statutes of the Purity of Blood"), first set down in 1449 for the council of the city of Toledo, are considered by some authors to anticipate the Nuremberg Race Laws. The racist doctrine of "purity of blood" stigmatized an entire ethnic group on the basis of criteria that those affected could not change either through conversion or assimilation.

The Christian community of faith, to which everyone actually belonged who became a part of the community through baptism, had become a community of descent, a racial equivalent - a process in which, almost 500 years before National Socialism, the racist ideologem of the "people's body" with its accompanying ideas, for example, of the "impurity of Jewish blood", was heralded.

This medieval racism, however, initially remained embedded in the context of mythical and religious ideas; there was no reference to a biology based on natural science. Only when religious certainties were called into question and the separation between body and soul was abolished in favor of a materialistic-scientific worldview, were the intellectual-historical preconditions for a modern-style racism given. "Racism was able to develop into a complex form of consciousness to the extent that racist elements of consciousness were able to "emancipate" themselves from the theological ties of the Middle Ages." Pseudo-scientific theories of race are, in a sense, a "waste product of the Enlightenment," whose seemingly scientific argumentation was also and especially received by great Enlightenment thinkers. "With their passionate, sometimes bordering on fanaticism, desire to order the world 'logically,' with their mania for classifying everything, Enlightenment philosophers and scholars helped give centuries-old racist ideas an ideological coherence that made them attractive to anyone inclined to think abstractly."

Thus Voltaire wrote in 1755: "The race of the negroes is a species of man entirely different from ours, as that of the spaniels differs from that of the greyhounds [...] It may be said that their intelligence is not simply of a different nature from ours, it is far inferior to it." Originally metaphysically and religiously based, racism received another, a secular foundation through the Enlightenment.

If in 1666 the Leyden professor Georgius Hornius divided mankind into Japhetites (whites), Semites (yellows) and Hamites (blacks), because he believed according to biblical tradition that all mankind descended from the three sons of Noah, Japhet, Shem and Ham, then less than 20 years later, in 1684, the French scholar François Bernier presented a racial system in which he categorized people on the basis of external characteristics such as skin color, stature and facial shape into four to five unequally developed races. Whereas previously blacks had been cursed by Ham and Jews had been collectively "guilty of the murder of God", now "scientific" reasons were given to "prove" their "racial" otherness or inferiority.

Naturalists such as Carl von Linné, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, Immanuel Kant and many others catalogued and classified the animal and plant kingdoms, but also humanity as it was known at the time, thus creating the foundations of the "natural history of man", anthropology. But their work was burdened from the beginning by inherited myths and prejudices. In particular, the Scala Naturae, the "Ladder of Beings," handed down from medieval theology and adopted into secular modern science, played a weighty role. This concept assigned all life a fixed place in a hierarchy of "lower" and "higher" beings. On the one hand, it contributed to the formation of theories about evolution and higher development, but on the other hand, when applied to humans, it led to the differentiation of older and younger "racial strata", which were equated with "primitive" and "advanced". Thus the genus Homo was introduced in 1758 by Carl von Linné in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae. He had already distinguished four spatially separated varieties of anatomically modern humans on the basis of skin color, but now he expanded the characterization of these four geographic varieties of humans to include the traits of temperament and posture: Europeans, according to him, were distinguished from the other human varieties by the characteristics white, sanguineous, muscular ("albus, sanguineus, torosus"), Americans by the characteristics red, choleric, erect, ("rufus, cholericus, rectus"), the Asiatics by the characteristics yellow, melancholic, rigid ("luridus, melancholicus, rigidus"), and the Africans by the characteristics black, phlegmatic, flaccid ("niger, phlegmaticus, laxus"). "If anthropologists had confined themselves to classifying groups of men according to their physical characteristics, and had drawn no further conclusions from them, their work would have been as harmless as that of the botanist or zoologist, and merely its continuation. But it turned out at the very outset that those who made the classifications arrogated to themselves the right to sit in judgment on the characteristics of the groups of men they defined: by making extrapolations from physical characteristics to mental or moral ones, they established hierarchies of races." "Whatever Linné, Blumenbach, and other eighteenth-century ethnologists had intended, they were in any case the pioneers of a secular or "scientific" racism" (Fredrickson, p. 59).

By valuing phenotypic traits on the basis of aesthetic criteria and linking them to intellectual, character or cultural abilities, the racial typologies elaborated in the 18th century prepared the ground for the fully developed biological racism of the 19th and 20th centuries (cf. Fredrickson, pp. 61-63). Joseph Arthur Comte de Gobineau, whom Poliakov calls the "great herald of biologically colored racism," is considered the inventor of the Aryan master race and the founder of modern race theory, or the theoretical mastermind of modern racism, with his four-volume Attempt on the Inequality of the Human Races. The French nobleman explained the decline of his class as a consequence of racial degeneration. In addition, he predicted that the mixing of the blood of different races would inevitably lead to the extinction of mankind.

In the 20th century, distinctive forms of racism emerged in many countries, some of which became official ideologies of the respective states - examples are:

- The Jim Crow laws, the period of racial discrimination in the U.S. that peaked between 1890 and 1960

- the racial laws of the National Socialists in Germany and in other European countries between 1933 and 1945

- the apartheid regime in South Africa, which took its most extreme development after 1948

- the policy of the Australian government towards Aborigines

Since the UNESCO Declaration against the "race" concept at the UNESCO Conference Against Racism, Violence and Discrimination in 1995 in Stadtschlaining, Austria, not only any biological but also any sociological derivation of race-like categories has been outlawed. This outlawing is justified as follows:

- Criteria on the basis of which races are defined are arbitrarily selectable.

- The genetic differences between people within a "race" are on average quantitatively greater than the genetic differences between different "races".

- There is no correlation between distinctive physical characteristics such as skin colour and other traits such as character or intelligence.

The eminent Italian population geneticist Cavalli-Sforza, professor at Stanford University in California, concludes in his monumental work "The History and Geography of Human Genes" that there is no scientific basis for the differentiation of human races. The division of humanity into taxonomic subgroups is essentially arbitrary and cannot be reproduced by statistical methods. The minor genetic differences that are detectable at all between certain populations are very small due to the short evolutionary age of modern humanity and, moreover, presumably blurred almost beyond recognition by migrations and subsequent intermingling. Moreover, the visually conspicuous differences, such as skin color, do not correlate at all with these genetically defined population clusters. No population has its own genes, and even its own alleles are meaningless; significant differences exist only in their frequency. Depending on the genetic marker chosen, the genetic clusters are also defined differently and are not stable.

March 21 is the International Day Against Racism. In 2018, the focus there was on promoting tolerance, inclusion and respect for diversity. The UN Special Rapporteur on racism and xenophobia is E. Tendayi Achiume.

General current phenomena

In German-speaking countries, it is sometimes assumed that racism mostly takes the form of xenophobia (from Greek ξενοφοβία "fear of the foreign", from ξένος xénos "foreign", "stranger" and φοβία phobía "fear"). However, racism and xenophobia are not simply synonymous. Social scientist Dieter Staas points out that xenophobia can be racially motivated, but it does not have to be: When two social groups compete with each other for resources or have had bad experiences with each other, they are often hostile towards each other without devaluing the other in a racist way. However, a clear separation of the terms is only possible analytically; in reality, xenophobia often contains racist elements. The historian Georg Kreis also sees no sharp boundaries between racism and xenophobia: from the victim's point of view, it is of little importance to which analytical category an act is attributed. Both forms of discrimination merge into each other.

Racism is often not perceived as such, but as xenophobia. This assumption is supported by research in Switzerland, where, based on a study by the Federal Commission against Racism, it can be assumed that racism in the narrower sense is much more widespread in Switzerland than originally assumed. Thus, despite assimilation, integration and naturalization, blacks are still socially marginalized after decades and are rejected in job applications, sometimes even clearly citing skin color as a pejorative factor. In Germany, too, racism is considered a widespread phenomenon on the labour market, in vocational schools, in public authorities, on the housing market or in the public sphere, which makes it much more difficult for those affected to participate in society.

According to the Austrian cultural anthropologist Christa Markom, the term xenophobia is rejected in social science research because the word component -phobia trivialises or legitimises racism, as if racists were only guided by fear and therefore not in control of their actions.

In racism research, it is increasingly pointed out that racism is not an individual problem, but that racist knowledge is determined by social discourses. According to Arndt, racism is "linked to social conditions that are very resistant and resilient, perhaps even irreparable." This means that racism is "(k)now an individual problem" and therefore "cannot be dealt with individually." It also involves "realizing that sociopolitical identities have grown through the omnipresence of racism, past and present - that at the heart of racism is the construction and hierarchization of blacks and whites." Arndt describes the social aspects of these constructions, "In socialization shaped by racism, these constructs were mediated and underpinned global relations of power and domination. A reality of sociopolitical identities was created. We are not born Black or White, but made into them. This necessitates noticing and representing Black and White experiences and perspectives. Where this is ignored, racism cannot be overcome."

Since the 1990s, a change of perspective has also been taking place in academia. Thus - as in Critical Whiteness Studies - it is not primarily the objects of racism that are the object of research, but the structures that make racism possible.

In 2020, racism researchers Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter see a resurgence of racism in the Western world into the mainstream. However, (left-)liberal media, politicians and academics blame only the voters of right-wing parties, who often come from the working class and are themselves marginalized. This obscures how structural racism itself exists in the current capitalist-neoliberal version of the prevailing liberalism, while at the same time it has failed to deliver on its promise of social justice. In the media, the extreme right has often been reported as the "voice of the people", antagonistic to the currently supposedly perfect, tolerant and liberal society. In fact, however, the extreme right is merely a continuation and enhancement of the capitalist-neoliberal system. Real alternatives to the currently existing system - such as those presented by Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn and Jean-Luc Mélenchon - have not been presented as a valid alternative by the liberal mainstream and have even been more strongly opposed than the extreme right itself.

The United Nations Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide reported in early 2013 that the risk of religiously and ethnically motivated violence worldwide may be higher than ever before, citing tensions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sudan, and Syria as examples.

Racism in football

→ Main article: Racism in football

Questions and Answers

Q: What is racism?

A: Racism is the belief in the natural superiority of one race over another. It may involve prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism against people of a different race or ethnicity.

Q: How did racism manifest during the Holocaust?

A: During the Holocaust, Nazis in Germany believed that some races did not even deserve to exist and used this racist belief to justify killing many people who belonged to those races.

Q: How long has racism been around?

A: Racism has existed throughout human history.

Q: What are some of the consequences of racism?

A: Racism has caused wars, slavery, the creation of nations, and laws.

Q: How have leaders used racism to justify their actions?

A: Leaders often use racism as a way to make their actions seem all right by suggesting that certain groups are less than human. For example, Nazis used this idea to take over Slavic countries while white people in America used it to treat African Americans as property.

Q: Are there any other causes for wars and slavery besides racism?

A: Although racism has played a role in causing wars and slavery, it is not the only cause.

Search within the encyclopedia