Race (human categorization)

Race theories (collectively also referred to as racial science or race theory) are theories that divide humanity into different races. They were particularly influential in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but are now considered outdated and scientifically untenable. The races were primarily distinguished typologically on the basis of external (phenotypical) characteristics such as skin colour, hair or skull shape, but additional differences in the character and abilities of corresponding individuals were also frequently assumed or claimed.

In different social and political milieus and at different times, the term "race" has had different uses in attempts to group or classify people. In anthropology, race was used from the late 17th century until the end of the 20th century as a term for classifying people, and since the 19th century it has often been used synonymously with people. In addition, concepts of race related to human beings also emerged in ethnology and sociology.

Such subdivisions of mankind were in part only neutral attempts at classification, but in part they were also connected with evaluations, in that one allegedly differentiated between superior and inferior human races (racism) and claimed connections between racially determined characteristics and cultural development.

In biology today, the species Homo sapiens is neither divided into races nor into subspecies. Molecular biological and population genetic research since the 1970s has shown that a systematic division of humans into subspecies does not do justice to their enormous diversity and the fluid transitions between geographical populations. Moreover, it has been found that the obvious phenotypic differences in race theories are caused by very few genes, and that the majority of genetic differences in humans are instead found within a so-called "race". Moreover, skin color, for example, is an evolutionarily very labile trait, meaning that it has changed in relatively short periods of time as human populations have migrated across different latitudes. This is due to the fact that skin colour is under strong selection pressure. For example, anthropologists now believe that the first modern humans to migrate to Europe (Cro-Magnon man) were dark-skinned.

The division of humans into biological races thus no longer corresponds to the state of science. Nevertheless, the term is still sometimes used in biomedical research and in official language in some countries (such as the USA and Latin America). In this context, the word race is not used in a biological sense, but as a social category that is largely based on a self-assessment by the individuals concerned.

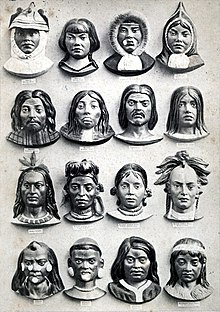

A systematic division of people into races, typical for the 19th century (after Karl Ernst von Baer, 1862).

Term History

The use of the word race is sporadically attested in Romance languages since the early 13th century. It became more common in the 15th century, mainly in the description of noble families and in horse breeding. In the following period, it was increasingly used for various types of human collectives, such as religious communities ("Christian race") or humanity as a whole ("human race"). It was probably first used to classify people in the sense of an anthropological taxonomy by François Bernier in 1684. In French and English, the term race "advanced to become a central concept in historiography" (Geulen); in German, on the other hand, it initially remained rather insignificant and only gained greater popularity in the late 19th century. Germany was (also in this respect) "a belated nation".

In biological anthropology, the division of the species Homo sapiens into different races was common until the late 20th century. In the post-war literature after the Second World War, the population-genetic definition of race predominated ("A race is a group of related, intermingling individuals, a population distinguished from other populations by the relatively great commonality of certain heritable characteristics"). Since the 1970s, however, genetic studies have increasingly cast doubt on the legitimacy of speaking of human races. In 1995, following the UNESCO conference "Against Racism, Violence and Discrimination" in Schlaining, eighteen internationally renowned human biologists and geneticists issued a "Statement on the Question of Race" in which they judged that the concept of race had "become completely obsolete" in its application to human diversity and called for it to be replaced "by views and conclusions based on today's understanding of genetic diversity". There is no longer any reason, from a biological and genetic perspective, to continue using the term "race." In 1996, the American Association of Physical Anthropologists published a statement that the concept of race as a definable group of people composed mainly of representatives with typical characteristics was scientifically untenable.

Encyclopaedias such as the Brockhaus or Meyers Lexikon refer to such typological/racial categories as "outdated" in their current editions (Brockhaus as of 2006). On the basis of recent scientific findings, in 2008 the German Institute for Human Rights spoke out against the use of the term "race" in legal texts in particular.

It continues to be used in Article 3 (3) of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. This also applies to Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as well as to Article 1, paragraph 1 of the 14th Additional Protocol to this Convention, which dates from 4 November 2000 and entered into force on 1 April 2005. However, these references to the term "race" are not to be regarded as legislative confirmations of a racial theory, but rather express that different treatment of people on the basis of their assignment to different races is discriminatory and therefore to be rejected. The explanatory memorandum to the General Equal Treatment Act states that the law does not assume the existence of human races, but that the person who behaves in a racist manner assumes this. The Act to Improve Inclusion Opportunities in the Labour Market of 20 December 2011 uses (in Art. 2 No. 18) the term "race".

In Norway, the term 'race' was removed from national laws dealing with discrimination by the legislator in 2010, as the term is considered problematic and unethical. The Norwegian law against discrimination only uses the terms ethnic and national origin, descent and skin colour.

In July 2018, the French National Assembly removed the word "race" from the constitution on the grounds that it was outdated.

For more on the usage and etymology of the word race, see race.

Criticism and overcoming

An early critic of the racial theories of Linné, Kant, and Blumenbach was Johann Gottfried Herder, who in his Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (1784-1791) rejected a division of humanity into races.

Around 1900, critical voices emerged in the German-speaking world that attributed to racial biology a share of the responsibility for increasing anti-Semitism and addressed anti-Semitic phenomena within biology and anthropology. However, the existence of human races was not fundamentally called into question; the criticism was directed specifically against the assumption of an Aryan and a Semitic (Jewish) race and against the valuation of races as higher or lower.

In response to the racist policies of the Nazis, Julian Huxley and Alfred C. Haddon wrote their 1935 book We Europeans: A Survey of Racial Problems, in which they argued that there was no scientific basis for the assumption of different, distinct races of people within Europe. They rejected such classifications based on phenotypical or somatic characteristics and assessments based on them as pseudo-scientific. They demanded that the term "race" be removed from the scientific vocabulary and that instead of human races we speak of "ethnic groups", since these have no biological reference but are defined sociologically. The biological systematization of European human types was a subjective process and the myth of racism merely an attempt to justify nationalism. However, they adhered to the subdivision of the whole of humanity into three major groups, although they suggested that in this case, too, we should no longer speak of races but of subspecies.

Until the 1990s, however, talk of human races remained common in biology. For example, Kindler's Encyclopedia Der Mensch (1982) contains two chapters on "The Racial Diversity of Mankind" and "Racial History and Racial Evolution," and in the Herder Encyclopedia of Biology from 1983 to 1987, reprinted in 1994, the entry Human Races begins with the words: "Like other biological species, today's Homo sapiens (man) is also divided into relatively uniform races with characteristic gene combinations in each case." Accordingly, historian Imanuel Geiss, in his 1988 History of Racism, also called the existence of human races "undeniable in their elementary nature as a real-historical reality."

Population geneticists such as Richard Lewontin and Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza have argued since the 1970s that external differences such as skin and hair color, hair texture, and nose shape are merely adaptations to different climates and diets, determined by only a small subset of genes. In fact, North American Indians resemble Europeans more than South American Indians in the external characteristics traditionally used to distinguish races, although they are much more closely related to the latter in origin, and Australian Aborigines, long isolated from the rest of humanity, appear relatively similar to black Africans.

The geneticists used the biological concept of population. To distinguish it from the unsuitable concept of race, however, Cavalli-Sforza defined it for humans more statistically than biologically: "A group of individuals inhabiting a precisely defined space, of whatever kind." A (human) population thus corresponds to the heterogeneous population of an area and not to a (supposedly homogeneous) race. An arbitrarily chosen delimitation is chosen, which does not refer to any typological characteristics. It may be irritating that the old race designations are nevertheless found in human genetic studies. Here, the boundaries of populations were deliberately drawn according to racial theories in order to subsequently disprove them. Cavalli-Sforza writes in this connection: "Of course, one must select the populations to be studied in such a way as to obtain interesting results."

In the Declaration of Schlaining in 1995, a group of scientists declared that the distinction of human races as inherently homogeneous and clearly distinguishable populations had proved untenable due to recent advances in molecular biology and population genetics. The genetic diversity of mankind is only of a gradual nature and does not reveal any major discontinuities. Therefore, any typological approach to the subdivision of mankind is unsuitable. Furthermore, the hereditary differences between different groups of humans were only small compared to the variance within these groups. To assume fundamental genetic differences on the basis of external differences, which are only adaptations to different environmental conditions, is a fallacy. The American Association of Anthropologists issued a statement in 1998 that was consistent in tenor but tailored to the special, historically conditioned circumstances in the USA.

Population genetic studies showed that about 85 % of the genetic variation is found within such populations as the French or the Japanese. By contrast, the genetic differences between the "races" traditionally distinguished on the basis of skin colour are comparatively small, at around 6 to 10 %. In addition, even these supposedly race-specific differences do not reveal clear boundaries when the geographical distribution is examined more closely. The transitions between the "races" (with the exception of the Australian Aborigines) are fluid. These empirical findings, made possible by advances in DNA and protein sequencing, have led the vast majority of anthropologists today to reject a division of humanity into races.

The discrepancy between the difference in external appearance and the uniformity of the genetic make-up is explained by Luca and Francesco Cavalli-Sforza in their book Different and yet the same (1994) as follows:

"The genes that respond to climate [in the course of evolution] affect the external features of the body because adaptation to climate requires, above all, a change in the surface of the body (which is, so to speak, the interface between our organism and the outside world). Precisely because these features are external, the differences between races are so striking that we believe equally glaring differences exist for all the rest of the genetic constitution. But this is not true: With respect to the rest of our genetic constitution, we differ from one another only slightly."

The argument that the genetic variance within a group of Homo sapiens is greater than that between different groups was criticised in 2003 by the geneticist and evolutionary biologist Anthony W. F. Edwards: The statement is only true if one considers alleles at a single gene locus. However, if intercorrelation patterns between different genes and the resulting gene clusters are considered, as they can be obtained using modern methods such as cluster analysis or principal component analysis, the picture is reversed. Edwards argues that it is possible to assign an individual to a specific, biologically defined group if a certain number of genes are considered instead of just individual genes. The article in which he presented his reasoning was called "Lewontin's fallacy" in reference to his colleague. In 2007, his colleague David J. Witherspoon was able to confirm this thesis experimentally by recording several hundred loci simultaneously using multilocus sequence typing. However, it remains questionable to what extent references to the socio-cultural "concept of race" can be derived from these genetic variations.

Edwards' critique was rejected by biological anthropologist Jonathan M. Marks. Race theory sought to discover large clusters of people homogeneous within their own group and heterogeneous to other groups. Lewontin's analysis showed that such groups do not exist in the human species, and Edwards' critique does not contradict this interpretation.

The anthropologist Ulrich Kattmann is of the opinion "that the racial classifications of anthropologists from the beginnings until today are not based on natural science, but originate from everyday ideas and socio-psychological needs". Moreover, they are fundamentally associated with judgmental discrimination and are therefore racist. As an example of the social-psychological conditionality, Kattmann cites the largely arbitrary construction of skin colours. Thus, since Linné, the Chinese have been called "yellow", although their skin is by no means yellow, but corresponds in average pigmentation to that of "white" southern Europeans. Neither are the Indians, the indigenous peoples of America, red.

In the German-speaking world, as the historian of science Veronika Lipphardt writes, racial biology "in the historical retrospect of National Socialism [...] became virtually the epitome of pseudoscience." In this context, "race theorists," namely Gobineau and Chamberlain, are considered "non-scientific," and from them "a direct line" leads to Hitler's Mein Kampf and to the extermination policies of the Nazi state. Since the defeat of National Socialism in 1945, racial biology had been exposed as a false doctrine and overcome. However, two findings speak against this narrative, Lipphardt continues. On the one hand, racial biology in Germany and elsewhere "had been called a pseudoscience long before 1945," and on the other hand, the history of racial biology did not end with the defeat of the Nazi regime, either in Germany or elsewhere. The concept of population offered new possibilities for studying human diversity. A division of humanity into a few groups had survived in various academic and non-academic contexts.

Cavalli-Sforza proposes 38 geographically distinct human populations according to their genetic relatedness and their membership in 20 language families, following Merritt Ruhlen's classification.

Since 2013, Brandenburg - like Thuringia from the beginning - dispensed with the concept of race in its constitution. Article 12(2) of the Constitution of the State of Brandenburg now reads: "No one may be favoured or disadvantaged because of descent, nationality, [...] or for racial reasons." Article 2(3) of the Constitution of the Free State of Thuringia reads: "No one shall be favoured or disadvantaged on account of origin, descent, ethnicity, [...]."

In 2019, the German Zoological Society under Martin S. Fischer, Uwe Hoßfeld, Johannes Krause and Stefan Richter adopted the Jena Declaration, according to which the concept of race is "the result of racism and not its precondition". Other prominent members, such as the criminal biologist and politician Mark Benecke, welcomed the resolution and called for an amendment to Article 3 of the Basic Law. An article in Die Zeit saw the declaration primarily as a political signal at a time when racist ideas were moving further and further into the centre of society. Felix Klein, the German government's anti-Semitism commissioner, also advocated removing the term "race" from the Basic Law, arguing that the term was "a social construct." On the other hand, Andrea Lindholz (CSU), chairwoman of the Bundestag's Committee on Interior and Home Affairs since 2018, expressed strong opposition to deleting the word "race" from the German constitution, calling it a "rather helpless[n] sham debate." A deletion could also complicate the administration of justice, she said. According to Stephan Hebel, however, this "racism of the middle" makes her "exemplary for a behavior that favors racist structures by tolerating them and refuses to resist them."

Global distribution of skin colors among indigenous populations, based on von Luschan's color scale.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the definition of the term race or racial group?

A: The term race or racial group refers to dividing the human species into groups based on visual traits such as skin color, cranial, facial features, or type of hair.

Q: What are the most widely used human racial types?

A: The most widely used human racial types are those based on visual traits such as skin color, cranial, facial features, or type of hair.

Q: What does modern biology say about the existence of human races?

A: Modern biology says that there is only one human race.

Q: What is the meaning of the word race in sociology?

A: In sociology, the word race refers to how people react differently to individuals based on their visual traits, such as skin color.

Q: Why do census forms sometimes ask people to describe their ethnic origin?

A: Census forms sometimes ask people to describe their ethnic origin as a way of asking "what racial group do you think you are?"

Q: Is it accurate to divide humans into races based on visual traits?

A: No, modern biology states that there is only one human race, and dividing humans into races based on visual traits is not accurate.

Q: Why do people react differently to individuals based on their visual traits, such as skin color?

A: People react in different ways to individuals based on their visual traits, such as skin color, due to societal factors, such as stereotypes and prejudices.

Search within the encyclopedia