Prussia

![]()

This article is about the Prussian state. For other meanings, see Prussia (disambiguation).

Prussia was a country on the Baltic Sea, between Pomerania, Poland, and Lithuania, that had existed since the late Middle Ages. After 1701, its name was applied to a much larger state that grew out of Brandenburg-Prussia and eventually encompassed almost all of Germany north of the Main River and lasted until the end of World War II.

Originally, the name Prussia only referred to the core of the Teutonic Order state in the former tribal territory of the West Baltic people of the Prussians and the dominions outside the Holy Roman Empire that had emerged from it. After the Hohenzollern Elector of Brandenburg, as Duke in Prussia, had assumed the title of King in Prussia in 1701, the overall designation of the Kingdom of Prussia became established for all the possessions of his house within and outside the empire. In the middle of the 18th century, the country rose to become the second German and fifth major European power and subsequently played a significant role in the concert of powers.

A member state of the German Confederation since 1815, the Kingdom of Prussia became the pre-eminent power of the North German Confederation in 1866 and the driving force behind the founding of the German Empire in 1871. After 1918, in the Weimar Republic, it was considered a "bulwark of democracy" as the Free State of Prussia. After the Prussian Strike of 1932 and the Gleichschaltung of the Länder during the National Socialist era, the Free State lost its autonomy. In 1947, the Allied Control Council also declared Prussia de jure dissolved.

The capital of the Duchy and later Kingdom of Prussia was Königsberg, the capital of the whole state was Berlin.

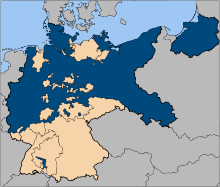

The situation of Prussia and Austria within and outside the German Confederation (1815-1866) Border of the German Confederation 1815

.svg.png)

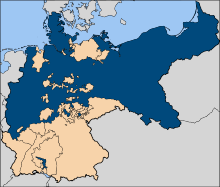

The greatest expansion of the Prussian state (1866-1918)

.svg.png)

Flag of the Kingdom of Prussia existing from 1701 to 1918

.svg.png)

Flag of the Free State of Prussia existing from 1918 to 1933

Overview

The original historical landscape of Prussia, named after its Baltic natives, the Pruzes, corresponded roughly to the later East Prussia. After the Teutonic Order had subjugated the Prussian land, for which it was not subject to any secular feudal lord due to the Papal Bull of Rieti (1234), it formed, together with Pomerelia, the centre of the Teutonic Order state. Its territory was divided in 1466 in the Second Peace of Thorn: into Royal Prussia, which was directly subordinate to the Polish crown and included Pomerelia, and into the Restordensstaat, which had to recognise Polish feudal sovereignty. The secularization of the latter in 1525 created the secular Duchy of Prussia, which fell by inheritance to the Electors of Brandenburg in 1618. They now ruled both lands in personal union.

Elector Frederick William was able to free the duchy from Polish feudal dependence in 1657. Since it lay outside the imperial borders, he was now a sovereign ruler there. His son Elector Frederick III took advantage of this to crown himself King of Prussia as Frederick I in 1701. The centre of the Hohenzollern dominion remained the Mark Brandenburg. In the Silesian Wars initiated by Frederick II, the state now known as the Kingdom of Prussia rose to become the second major German and fifth major European power. In the same epoch Prussia developed into a centre of the Enlightenment in Germany. After its defeat by Napoleonic France, Prussia lost large parts of its territory in 1806, but only a few years later, as a result of Stein-Hardenberg's reforms and its victorious participation in the wars of liberation, it gained more power and prestige than before.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 brought Prussia considerable territorial gains, especially in western Germany. In the newly founded German Confederation, it was the most important power after Austria. In the course of the March Revolution of 1848, the idea of a unification of the German Empire under Prussian leadership arose for the first time. Although King Frederick William IV declined the imperial crown offered to him by the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1849, the national liberal movement increasingly pinned its hopes for a united Germany on Prussia. Prussia's victory in the German War in 1866 led to Austria's exclusion from Germany and the dissolution of the German Confederation. In its place, Prussia formed the North German Confederation with the German states north of the Main River. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the southern German states, with the exception of Luxembourg, also joined the Confederation. Prussia was since then the dominant federal state of the newly founded German Empire and its king bore the additional title German Emperor as its head.

After the fall of the monarchy in the November Revolution of 1918, the kingdom became the republican Free State of Prussia, which proved to be a bulwark of democracy during the Weimar Republic. However, in the so-called Preußenschlag, its state government was stripped of its power by the Reich government in 1932. The Prussian ministers were replaced by Reich commissioners and their ministries were merged with the corresponding Reich departments in 1934 as part of the National Socialist policy of Gleichschaltung. With Control Council Law No. 46 of 25 February 1947, the Allied Control Council of the four occupying powers in Germany decreed the legal dissolution of Prussia. De facto, it had already ceased to exist as a state at the end of the war in 1945.

Both the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany and many of their states have continued Prussian traditions. The territories that formed the Prussian state until 1918 - at the time of its greatest expansion - now belong to Germany and six other states: Belgium, Denmark, Poland, Russia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic.

History

The later Kingdom of Prussia developed essentially from two parts of the country, both ruled by princes from the House of Hohenzollern: from the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which belonged to the seven electorates of the Holy Roman Empire, and from the Duchy of Prussia, which in turn had emerged from the state of the Teutonic Order.

Teutonic Order State and Duchy

→ Main article: Teutonic Order State and Duchy of Prussia

After several unsuccessful attempts to conquer the tribal territories of the pagan Prussians, the Polish Duke Conrad of Mazovia called on the Teutonic Order for help in 1209 and was prepared to grant it land rights in the territories to be conquered. These plans took shape after in 1226 Emperor Frederick II entrusted the Grand Master of the Order, Hermann of Salza, with the so-called "heathen mission" in Prussia in the Golden Bull of Rimini. In 1234 the rights of the Order were also confirmed by the Pope. With the year 1226 the formation of the Order's state in Prussia began, which was connected to the Holy Roman Empire, but was not a part of it.

After the forcible Christianization of the Prussians and the conquest of their land were completed, the knights of the Order increasingly fell into a crisis of legitimacy. In addition, there were conflicts with the neighbouring countries of Poland and Lithuania. In the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410, the Knights of the Order finally suffered a decisive defeat against Poland and Lithuania. In 1466, in the Second Peace of Thorn, the Order had to cede the west of its territory and to acknowledge the feudal sovereignty of the Polish Crown for the rest. From then on, West Prussia and Warmia were directly subject to the Polish crown as Royal Prussia.

The remaining territory of the Order's state comprised approximately the later East Prussia without the Warmia. The Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach initially waged war against Poland, especially against Royal Prussia with Warmia. When the hoped-for support from the Empire failed to materialize, he changed his policy: On the advice of Martin Luther, he converted the territory of the Order into a secular duchy hereditary to the House of Hohenzollern, introduced the Reformation and took it in fief from the hand of the Polish King Sigismund I in Krakow on April 8, 1525. Like the duke, his subjects also became Protestants.

Since the Pope and the Emperor did not recognise either the second Peace of Thorn or the secularisation of the Order's state, the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order continued to be formally regarded as sovereigns of the Prussian territories at the Imperial Diet for a long time.

The Mark Brandenburg and the Hohenzollerns

→ Main article: Mark Brandenburg and Hohenzollern

The actual nucleus of the later Hohenzollern state of Prussia was the Mark Brandenburg. It had been founded in 1157 by the Ascanian Albrecht I, after he had finally conquered the territory settled by Slavs. Albrecht regarded the territory as an allodial possession and since then called himself "Margrave in Brandenburg". After the death of the last Ascanian Margrave Waldemar in 1320, the land first fell to the Wittelsbach dynasty, then in 1373 to the Luxembourg dynasty.

The fact that Brandenburg finally fell to the then comparatively insignificant House of Hohenzollern was due to the disputed election of king in 1410. After the death of King Ruprecht, Sigismund of Luxembourg and his cousin Jobst of Moravia stood for election. In addition, both claimed the title and vote of Elector of Brandenburg. Sigismund sent his brother-in-law, Burgrave Frederick VI of Nuremberg, as his representative to the Electoral College to cast the Brandenburg vote for him. Thus he initially prevailed against his cousin, who was considered the favourite, with 4:3 votes for the course. On October 1, 1410, however, the other electors recognized Jobst's claim to the Electorate of Moravia as legitimate, so that he was elected Roman-German king. However, Jobst of Moravia died on 18 January 1411 for unknown reasons. The crown now finally went to Sigismund. In gratitude for Frederick's services in the first election, and to pay off his debts to him, King Sigismund granted Hohenzollern the hereditary dignity of Margrave and Elector of Brandenburg in 1415. In 1417 he formally enfeoffed him with the Kurmark and the office of arch chamberlain. In return, the wealthy Frederick granted his brother-in-law loans with which he could cover his war expenses in Hungary.

Frederick was descended from the Franconian line of the Hohenzollerns and had been Burgrave of Nuremberg since 1397. In the years after 1411, he secured his supremacy in the country in years of fighting against the reluctant aristocracy of the Mark. As Frederick I of Brandenburg, he combined the titles Elector of Brandenburg, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. He founded the Brandenburg line of his house, which was later to provide all the kings of Prussia and, from 1871 to 1918, the German emperors.

Brandenburg-Preußen (1618-1701)

→ Main article: Brandenburg-Prussia

In 1618, the ducal Prussian line of the House of Hohenzollern became extinct in the male line. Their heirs, the Margraves and Electors of Brandenburg, ruled both lands in personal union from then on. They were thus in fealty to both the Emperor and the King of Poland. The designation Brandenburg-Prussia for the widely separated Hohenzollern dominions is not contemporary, but has become common in historiography to designate the transitional period from 1618 to the founding of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 and at the same time to emphasize the continuity between the Electorate of Brandenburg and the Kingdom of Prussia.

Thirty Years' War

A few years before the Thirty Years' War, Brandenburg had also been able to secure rule over the Duchy of Cleves and the counties of Mark and Ravensberg in the west of the empire in the Jülich-Klev succession dispute. The country was initially spared from the war itself. In 1625, however, the Danish-Lower Saxon War broke out, in which several Protestant states of northern Germany, led by Denmark and supported by England and the States General, opposed the Catholic League and the Emperor. After the defeat of the Danish army at Dessau in April 1626, imperial troops invaded the Mark. Elector George William, who had no forces to speak of, retreated to the Duchy of Prussia, which lay outside the empire, and in 1627 was forced to form an alliance with the emperor. From then on, Brandenburg served as a deployment and retreat area for the imperial troops.

On 6 July 1630 the Swedish King Gustav Adolf landed on Usedom with 13,000 men. This marked the beginning of a new phase of the Thirty Years' War. When Gustav Adolf entered Brandenburg in the spring of 1631, he forced the Elector, his father-in-law, into an alliance. After the Swedish troops were crushingly defeated at the Battle of Nördlingen on September 6, 1634, the Protestant alliance broke apart. Brandenburg entered into a new alliance with the emperor. The Kurmark was now occupied alternately by enemies and allies. The Elector again retreated to Königsberg in Prussia, where he died on December 1, 1640.

The new Elector was his son Frederick William. The primary goal of his policy was to pacify the country. He tried to achieve this through a settlement with Sweden, which was valid for two years from 24 July 1641. In negotiations with the Swedish Imperial Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, the Brandenburgers succeeded in negotiating a treaty on May 28, 1643, which formally returned the entire country to the electoral administration. However, until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, individual strongholds in Brandenburg remained occupied by the Swedes. In the Peace of Westphalia, Brandenburg-Prussia was then able to acquire Hinterpommern, the High Diocese of Halberstadt and the Principality of Minden, as well as the claim to the Archdiocese of Magdeburg, which accrued in 1680. The territorial gains together amounted to about 20,000 km².

Consolidation and reform policy of the Great Elector

Brandenburg was one of the German territories most affected by the Thirty Years' War. Vast areas were devastated and depopulated. To spare the state from being the plaything of more powerful neighbors in the future, Frederick William, later called the Great Elector, pursued a cautious seesaw policy between the great powers after the war, as well as building up a powerful army and an efficient administration. He built up a standingarmy that made Brandenburg a sought-after ally of the European powers. This enabled the Elector to receive subsidy payments from several sides. He pursued the establishment of his own Electorate of Brandenburg navy and in later years pursued colonial projects in West Africa and the West Indies. After the foundation of the fortress of Groß Friedrichsburg in 1683 by the Brandenburg African Company in what is now Ghana, Brandenburg participated in the international slave trade.

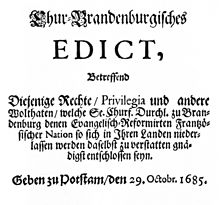

Domestically, Frederick William carried out economic reforms and initiated extensive peupling measures to develop his economically weakened state. Among other things, in the Edict of Potsdam in 1685 - his response to King Louis XIV's Edict of Fontainebleau - he invited thousands of Huguenots expelled from France to settle in Brandenburg-Prussia. At the same time, he disempowered the estates in favor of an absolutist central administration. He thus laid the foundation for the Prussian civil service, which since the 18th century enjoyed a reputation for particular efficiency and loyalty to the state.

The Elector succeeded in 1657 in the Treaty of Wehlau to release the Duchy of Prussia from Polish suzerainty. In the Peace of Oliva of 1660, the sovereignty of the Duchy was finally recognized. This was a decisive prerequisite for its elevation to a kingdom under the son of the Great Elector. Victory in the Swedish-Brandenburg War (1674-1679) enabled the country to further expand its position of power despite failing to gain land. During his reign, Frederick William had made Brandenburg, which had previously been comparatively insignificant, the second most powerful territory in the empire after Austria. This laid the foundation for the later kingdom.

At the instigation of Frederick William and his Oranian wife Luise Henriette, eminent Dutch scholars, especially from Leiden University, contributed to the modernization of the Brandenburg-Prussian state. "Through the Leiden philosopher Justus Lipsius there was an effective contact between Calvinism and Neo-Stoicism, which, with their demand for active engagement, hard performance of duty, and inner discipline, henceforth became elements of officialdom, the elite of which was trained almost without exception in Holland. In Leiden, Samuel von Pufendorf had also adopted the basic features of natural law thought from Hugo Grotius."

Kingdom of Prussia (1701-1918)

→ Main article: Kingdom of Prussia

Achievement of the royal dignity by Frederick I (1701-1713)

The rank, reputation and prestige of a prince were important political factors in the age of absolutism. Elector Frederick III therefore used the sovereignty of the Duchy of Prussia to seek its elevation to a kingdom and his own to king. In doing so, he sought above all to maintain equality of rank in relations with Saxony with the Elector of Saxony, who was also King of Poland, and with the Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg ("Elector Hanover"), who was a pretender to the English throne.

Since there could be no crown within the Holy Roman Empire other than that of the Emperor, Elector Frederick III sought the kingship for the Duchy of Prussia and not for the actually more important part of the country, the Mark of Brandenburg. Emperor Leopold I finally agreed that Frederick should receive the title of king for the Duchy of Prussia, which did not belong to the Empire. Elector Frederick III crowned himself on 18 January 1701 in Königsberg and became Frederick I, King in Prussia.

The restrictive title "in Prussia" was necessary because the designation "King of Prussia" would have been understood as a claim to rule over the entire Prussian territory. However, since Warmia and western Prussia (Pomerelia) were still under the sovereignty of the Polish crown at the time, this would have provoked conflicts with the neighbouring country, whose rulers still claimed the title of "King of Prussia" until 1742. From 1701 onwards, however, the name Kingdom of Prussia gradually became established in common German usage for all territories ruled by the Hohenzollerns - whether located within or outside the Holy Roman Empire. The centres of the Hohenzollern state remained the capital Berlin and the summer residence Potsdam. All royal coronations, however, traditionally took place in Königsberg.

Frederick I largely left the political business to the so-called Three Counts Cabinet. He himself concentrated on a lavish court life of the Prussian Court based on the French model, which brought his state to the brink of financial ruin. He financed the pomp and circumstance at court by, among other things, leasing Prussian soldiers to the Alliance in the War of the Spanish Succession. When Frederick I died on 25 February 1713, he left behind a mountain of debt amounting to twenty million talers.

Centralization and militarization under Frederick William I (1713-1740)

Frederick I's son, Frederick William I, was not ostentatious like his father, but thrifty and practical. Consequently, he cut court expenses to a minimum. Everything that served courtly luxury was either abolished or put to other uses. All the king's austerity measures were aimed at the development of a strong standing army, in which the king saw the basis of his power both internally and externally. This attitude earned him the nickname "Soldier King". Nevertheless, Frederick William I led a short campaign only once during his reign, in the Great Northern War during the siege of Stralsund. In its aftermath, Prussia gained not only part of Western Pomerania, but also international prestige thanks to the prestigious victory over the Swedes.

Frederick William I revolutionized the administration, among other things, with the establishment of the Directorate General. He thus centralized the country, which until then had still been territorially fragmented, and gave it a unified state organization. Through a mercantilist economic policy, the promotion of trade and commerce, and a tax reform, the king succeeded in doubling annual state revenues. To attract the necessary skilled workers, he introduced compulsory education and established chairs of economics at Prussian universities, the first of their kind in Europe. In the course of an intensive peupling policy, he had people from all over Europe settled in his sparsely populated provinces.

When Frederick William I died in 1740, he left behind an economically and financially stable country. With him, however, also began the militarization of Prussia, although its extent and effects are disputed.

Rise to great power under Frederick II (1740-1786)

On 31 May 1740 his son Frederick II - later called Frederick the Great - ascended the throne. In the very first year of his reign, he ordered the Prussian army to march into Silesia, which belonged to Austria and to which he laid claim. This was the beginning of the Prussian-Austrian dualism, the struggle of the two leading German powers for supremacy in the empire.

The three Silesian Wars (1740-1763) succeeded in securing the newly won province for Prussia. In the third, the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Prussia, allied with Great Britain, faced a coalition of Austria, France, Russia, and Saxony and, despite great military successes, came to the brink of collapse. It was saved from defeat only by the failure of Austria and Russia to conquer Berlin together after Frederick's crushing defeat at the Battle of Kunersdorf ("Miracle of the House of Brandenburg"), and by the death of Tsarina Elizabeth. Her successor, Tsar Peter III, was an admirer of Frederick and detached Russia from the alliance. His enemies were thus compelled to come to an understanding with Frederick, and in the peace of Hubertusburg conceded to him the final possession of Silesia. Prussia, whose army was now considered one of the best in Europe, had risen to become the fifth great power.

Frederick II was a representative of enlightened absolutism and saw himself as the "first servant of the state". Thus he abolished torture, reduced censorship, laid the foundation for the General Prussian Land Law and brought more exiles into the country by granting complete religious freedom. Under his reign, the expansion of the country was pushed forward, as was the peopling of previously largely unsettled areas, such as the Oder and the Netzebruch.

Together with Austria and Russia, Frederick pursued the partition of Poland. In the first partition in 1772, he acquired Polish Prussia, which was incorporated into West Prussia, the Netzedistrict and the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia, which became part of East Prussia. Thus the Hohenzollern territories of Pomerania and East Prussia were no longer separated by Polish territory. In addition, all Prussian territories now belonged to the Hohenzollern state, so that Frederick could now call himself King "of Prussia". He died on 17 August 1786 at Sanssouci Palace.

Stagnation and end of the Prussian feudal state (1786-1807)

After the death of Frederick II, his nephew Frederick William II (1786-1797) ascended the Prussian throne. In the 1790s Berlin grew into a respectable city influenced by classicism. Here, as throughout the empire, the growing educated middle classes took a mostly positive view of the French Revolution. Since 1794, Prussia had been governed by the General Law of the Land, a comprehensive body of laws, the drafting of which had already begun under Frederick II.

In foreign policy, Prussia forced Austria into a separate peace in the Russo-Austrian Turkish War in 1790 through an alliance with the Ottoman Empire. Frederick William continued the policy of partition towards Poland, so that Prussia was able to secure further territories as far as Warsaw in the second and third partitions of Poland (1793 and 1795). From them the new provinces South Prussia (1793), New East Prussia and New Silesia (both 1795) were formed. The population thus initially grew by 2.5 million, but the new acquisitions were lost again after the defeat by France in 1806.

The French Revolution brought about a rapprochement between Austria and Prussia. Although the Prussian government had initially viewed the revolution favorably, it formed a defensive alliance with Austria on February 7, 1792. Because of the Pillnitz Declaration in favor of King Louis XVI, France declared war on both countries on April 20, 1792. In the First Coalition War, the initial rapid advance after the Cannonade of Valmy was followed by the withdrawal of Prussian and Austrian troops from France. Subsequently, French revolutionary troops advanced as far as the Rhine. After the Peace of Basel in 1795, Prussia left the anti-French alliance for more than a decade. Frederick William II died on November 16, 1797, and was succeeded by his son Frederick William III. (1797-1840) on the throne.

Between 1795 and 1806, Prussia benefited from a foreign policy that favored France. With France's support, it became the de facto superpower of northern Germany. In the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, it received as compensation for losses on the left bank of the Rhine a large part of the Hochstift Münster, the bishoprics of Hildesheim and Paderborn, and other territories. This increased its territory by about 3 and its population by about 5 percent. In addition, Prussia briefly occupied the Electorate of Hanover, which was associated with Great Britain.

When negotiations with France on the division of the spheres of power in Germany failed in 1806, war broke out again. In the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt, Prussia suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Napoleon I's troops, which meant the demise of the previous old Prussian state. In the Peace of Tilsit in 1807 Prussia lost about half of its territory: all areas west of the Elbe as well as the gains from the second and third Polish partition. In addition, the country had to accept a French occupation, supply the foreign troops and pay high tribute payments to France. Prussia effectively lost its position of great power and was, in terms of size and function, only a buffer state between France and Russia.

State reforms and wars of liberation (1807-1815)

→ Main article: Prussian reforms

However, the conditions of the Peace of Tilsit, which were perceived as intolerable, also brought about a renewal of the state. The fundamental reforms undertaken after 1807 were aimed at changing the conditions that had led to the defeat of 1806 in terms of domestic policy and at shaking off French hegemony in terms of foreign policy. The Stein-Hardenberg reforms, led by Freiherr vom Stein, Scharnhorst, and Hardenberg, modernized the state. In 1807 the serfdom of the peasants was abolished, in 1808 local self-government was introduced and in 1810 freedom of trade was granted. The envoy Wilhelm von Humboldt, who had been recalled from Rome, reshaped the education system and founded the first Berlin University in 1809, which today bears his name. The army reform was completed in 1813 with the introduction of universal conscription.

Prussia took part in Napoleon's Russian campaign of1812 as an ally of France. After the defeat of the "Grande Armee", however, the Prussian Lieutenant General Count Yorck concluded the Convention of Tauroggen with the General of the Russian Army Hans von Diebitsch as early as 30 December 1812. It provided for an armistice and stated that Yorck should withdraw his Prussian troops from the alliance with the French army. Yorck acted on his own initiative, without orders from his king, who continued to waver for several months between enforced loyalty to the alliance with France and a policy friendly to Russia. The Convention of Tauroggen was understood in Prussia as the beginning of the revolt against French foreign rule. Finally, Frederick William also forced himself to change his policy. When he called for a liberation struggle on March 20, 1813, in the Silesian privileged newspaper with his appeal "To My People", dated March 17, 300,000 Prussian soldiers (6% of the total population) were ready. Universal conscription was introduced for the duration of the impending war. Prussian troops under Blücher and Gneisenau made decisive contributions to the victory over Napoleon in the Battle ofLeipzig in 1813, in the Allied advance to Paris in the Spring Campaign of 1814, and in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

From the Restoration to the March Revolution (1815-1848)

→ Main article: German dualism

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Prussia regained most of the territory it had held since 1807. The rest of Swedish Pomerania and the northern part of the Kingdom of Saxony were added. Prussia also gained considerable territories in the west, which it soon combined with former western territory to form the Province of Westphalia and the Rhine Province. In the new provinces in the west, mighty fortresses were built in Koblenz, Cologne and Minden, built in the New Prussian fortification style, to secure the Prussian supremacy. Although Prussia regained the formerly Polish province of Posen, which had become part of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, it lost territories from the second and third Polish partitions to Russia. Since then, the Prussian state consisted of two large but geographically separate blocks of states in eastern and western Germany. Prussia became a member of the German Confederation.

Frederick William III did not keep the promise made to his people during the wars of liberation to give the country a constitution. Unlike in most other German states, Prussia also did not create a people's representation for the entire state. Instead of a Landtag for the whole of Prussia, only provincial Landtage were convened. The law of 5 June 1823 granted them the right to have a say. Conditions therefore prevailed as in a Ständestaat, because apart from the influential nobility in the provinces, the towns had self-administration, although there was a certain degree of state supervision.

The royal government thus believed that it could prevent liberal aspirations for a constitutional monarchy and democratic participation rights. On the foreign policy level, the Holy Alliance, which Frederick William III established together with the Tsar of the RussianEmpire and the Emperor of Austria, served the goal of suppressing democratic efforts throughout Europe.

However, the royal government's efforts to combat liberalism, democracy and the idea of unifying Germany were countered by strong economic constraints. Due to the division of its territory into two parts, the economic unification of Germany after 1815 was in Prussia's very own interest. The kingdom was therefore one of the driving forces behind the German Customs Union, of which it became a member in 1834.

Due to the success of the Zollverein, more and more supporters of German unification pinned their hopes on Prussia replacing Austria as the leading power of the Confederation. The Prussian government, however, did not want to commit itself to the political unification of Germany.

The hopes that Frederick William IV's accession to power had initially raised among liberals and supporters of German unification were soon dashed. (1840-1861) had initially aroused among liberals and supporters of German unification were soon disappointed. The new king also made no secret of his aversion to a constitution and an all-Prussian Landtag.

However, the large amount of money needed for the construction of the Eastern Railway, which was demanded by the military, required the approval of budgets from all provinces. That is why the United Diet was finally convened in the spring of 1847. Already in his opening speech, the king made it unmistakably clear that he regarded the Diet only as an instrument for the appropriation of money and that he did not want to see any constitutional questions discussed. However, since the majority of the Landtag demanded from the outset not only budgetary appropriation but also parliamentary control of the state's finances and a constitution, the body was dissolved again after only a short time. Prussia thus faced a constitutional conflict even before the outbreak of the March Revolution.

After the popular uprisings in southwestern Germany, the revolution finally reached Berlin on March 18, 1848. Frederick William IV, who had initially had the insurgents shot, had the troops withdrawn from the city and now seemed to bow to the demands of the revolutionaries. The United Diet met once again to decide on the convening of a Prussian National Assembly, which met from 22 May to September 1848 in the Sing-Akademie in Berlin.

The Prussian National Assembly had been given the task by the Crown of working out a constitution together with it. However, the National Assembly did not agree to the government's draft for a constitution, but worked out its own draft with the Waldeck Charter. The constitutional policy of the Prussian National Assembly also led to a counter-revolution: the dissolution of the assembly and the introduction of an octroyed (decreed) constitution on the part of the head of state. This oktroyierte constitution retained some points of the Charte, but restored on the other hand central prerogatives of the crown. Above all, the introduced three-class suffrage decisively shaped the political culture of Prussia until 1918.

In the Frankfurt National Assembly, the proponents of a Greater German nation state initially prevailed, who envisaged an empire including the German-speaking parts of Austria. However, since Austria was only willing to agree to an imperial unification with the inclusion of all its territories, the so-called small German solution was finally adopted, i.e. a unification under Prussian leadership. Democracy and German unity failed in 1849, however, when Frederick William IV refused the imperial crown that the National Assembly had offered him. The revolution was finally put down in southwest Germany with the help of Prussian troops.

From the Revolution to the Founding of the Confederation (1849-1866)

While the revolution was still being suppressed, Prussia made another attempt at unification, but with a more conservative draft constitution and closer cooperation with the Mittelstaaten. Meanwhile, Austria attempted to impose a Greater Austria. After the political-diplomatic dispute between the two great German powers had almost led to war in the autumn crisis of 1850, Prussia finally abandoned its Erfurt Union. The German Confederation was restored almost unchanged.

During the era of reaction, Prussia and Austria again worked closely together to put down democratic and national movements; however, Prussia was denied equal rights. King William I ascended the Prussian throne in 1861. With War Minister Roon, he sought army reform that included longer terms of service and rearmament of the Prussian army. However, the liberal majority of the Prussian parliament, which had the budgetary power, did not want to approve the necessary funds. A constitutional conflict ensued, in the course of which the king considered abdicating.

As a last resort, Wilhelm decided to appoint Otto von Bismarck as prime minister in 1862. The latter was a vehement supporter of the royal claim to autocracy and ruled for years during the conflict period against the constitution and parliament and without a legal budget. Realizing that the Prussian crown could only gain popular support if it placed itself at the forefront of the German unification movement, Bismarck pursued an offensive policy that led to the three wars of unification.

With the so-called November Constitution of 1863, the Danish government attempted - contrary to the provisions of the London Protocol of 1852 - to bind the Duchy of Schleswig more closely to the Kingdom of Denmark proper, excluding Holstein. This triggered the German-Danish War in 1864, which Prussia and Austria fought together on behalf of the German Confederation. After the victory of the troops of the German Confederation, the Danish crown had to renounce the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg in the Peace of Vienna. The duchies were initially administered jointly by Prussia and Austria.

Soon after the end of the war with Denmark, a dispute broke out between Austria and Prussia over the administration and future of Schleswig-Holstein. Its deeper cause, however, was the struggle for supremacy in the German Confederation. Bismarck succeeded in persuading King Wilhelm, who had long been hesitant for reasons of loyalty to Austria, to adopt a belligerent solution. On Prussia's side, the Kingdom of Italy joined the war (→ Battle of Custozza and Naval Battle of Lissa), along with a number of small northern German and Thuringian states.

In the German War, Prussia's army under General Helmuth von Moltke won the decisive victory in the Battle of Königgrätz on 3 July 1866. In the Peace of Prague of August 23, 1866, Prussia was able to enforce its demands: Austria had to acknowledge the dissolution of the German Confederation, renounce participation in the "new shaping of Germany," and recognize the "closer federal relationship" that Prussia entered into with the German states north of the Main River. While Prussia incorporated several member states of the dissolved German Confederation, Austria remained territorially untouched at Bismarck's insistence and against King Wilhelm's opposition. This was a decisive prerequisite for the later alliance with the Danube Monarchy.

North German Confederation and the founding of the German Empire (1866-1871)

As a result of the German War, Prussia significantly increased its power. First, it formed a defensive alliance with its allies on August 18, 1866. The August alliance prepared the foundation of the North German Confederation. With the annexations of October 1866, Prussia officially annexed the territories already occupied during the war: the Kingdom of Hanover, the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel, the Duchy of Nassau, the Free City of Frankfurt and all of Schleswig-Holstein. From then on, almost all of northern Germany formed a closed Prussian territory. In addition, Prussia entered into so-called protective alliances with the formerly opposing southern German states of Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden. The only exceptions were Austria and Liechtenstein.

Domestically, Bismarck ended the Prussian constitutional conflict that had been smoldering since 1862 with the Indemnity Act. It granted the Prussian parliament the right to approve the budget, while granting Bismarck immunity from prosecution for his unconstitutional government actions. The right-wing liberals, later the National Liberals, supported the bill and worked closely with Bismarck. The left-wing liberals remained in opposition. Likewise, conservatives split on the question of whether to support Bismarck and his policies.

Prussia's policy towards Austria had only been possible because France remained neutral. Therefore, Bismarck had persuaded Napoleon III to tolerate this policy with vague promises to eventually surrender Luxembourg to France. Now, however, France was faced with a strengthened Prussia, which no longer wanted to know anything about the earlier territorial promises. In 1870, the dispute over the Spanish candidacy for the throne of the Catholic Hohenzollern Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen escalated, which Bismarck used to provoke a war with France. Following Bismarck's publication of the so-called Ems Dispatch, the French government declared war on Prussia. For the southern German states of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt, which was still independent south of the Main River, this was the beginning of an alliance.

After the rapid German victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing national enthusiasm throughout Germany, the southern German princes now also felt pressured to join the North German Confederation. Thereupon the foundation of the German Empire took place in the small-German version, which had already been planned by the National Assembly in 1848/49 as a model of unification. The Imperial Constitution, which came into force on 1 January 1871, entrusted the Federal Presidency to the Prussian King. In a proclamation in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, Wilhelm I assumed the title of "German Emperor" on January 18, 1871, the 170th anniversary of Frederick I's coronation as king. Therefore, not the 1st, but the 18th of January was later celebrated as the official Founding Day of the German Empire.

In the German Empire (1871-1918)

In the German Empire (1871-1918), German and Prussian politics always remained closely linked; for the King of Prussia was at the same time German Emperor and the Prussian Prime Minister - except for the brief terms of Botho zu Eulenburg and Albrecht von Roon - was always also Reich Chancellor.

Between 1871 and 1887, Bismarck led the so-called Kulturkampf in Prussia to push back the influence of Catholicism. However, resistance from the Catholic population and the clergy, especially in the Rhineland and in the former Polish territories, forced Bismarck to end the struggle without result. In the eastern parts of Prussia, most of which were inhabited by Poles, the Kulturkampf was accompanied by an attempt at a policy of Germanization.

Wilhelm I was succeeded in March 1888 by Frederick III, who was already seriously ill. He died after a reign of only 99 days. In June of the "Three Emperors' Year" Wilhelm II ascended the throne. He dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and from then on largely determined the politics of the country himself. This only changed in the course of the First World War, when both the Emperor and the Imperial Government largely ceded policy-making authority to the Supreme Army Command under Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff. The victorious powers, however, saw the Kaiser as one of the main culprits for the outbreak of war. In several notes in response to the German request for an armistice in October 1918, they urged him to abdicate. Wilhelm II initially considered abdicating only as German Emperor, but not as King of Prussia. Because of his hesitation, the revolutionary situation in Berlin intensified. To defuse it, Reich Chancellor Max von Baden announced on November 9 that the emperor would renounce both crowns without his consent. This was the de facto end of the monarchy in Prussia and Germany. On 28 November Wilhelm II also formally abdicated from exile in the Netherlands. The Prussian royal crown is now kept at Hohenzollern Castle near Hechingen.

See also: Silver column (Aron)

Free State of Prussia in the Weimar Republic (1918-1933)

→ Main article: Free State of Prussia

Prussia was proclaimed an independent Free State within the Imperial Union at the end of the Empire and was given a democratic constitution in 1920.

The territorial cessions of Germany stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles concerned - with the exception of the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine formed after the Franco-Prussian War and parts of the Bavarian Palatinate - exclusively Prussian territory: Eupen-Malmedy went to Belgium, Northern Schleswig to Denmark, the Hultschiner Ländchen to Czechoslovakia. Large parts of the territories of West Prussia and Posen, which Prussia had received as part of the partitions of Poland, as well as East Upper Silesia went to Poland. Danzig became a Free City under the administration of the League of Nations, and the Memelland came under Allied administration. As before the Polish partitions, East Prussia was separated from the rest of the country by Polish territory. It was accessible from the territory of the Reich by ship - with the East Prussia Maritime Service -, by air or by rail through the Polish Corridor. The Saar region, now administered by the League of Nations for 15 years, was also formed predominantly from Prussian territorial parts.

The annexation of the Free State of Waldeck represents a Prussian territorial addition during the Weimar Republic. This small state had already lost part of its sovereign rights to Prussia in 1868 through an accession treaty. After a referendum in 1921, the Waldeck district of Pyrmont initially became part of the Prussian province of Hanover. The cancellation of the accession treaty by Prussia five years later led to major financial problems in the remaining part of Waldeck, which was then finally incorporated into the Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau in 1929.

From 1919 to 1932, Prussia was ruled by governments of the Weimar Coalition (SPD, Zentrum and DDP), extended by the DVP from 1921 to 1925. Unlike in some other states of the Reich, the majority of democratic parties was not threatened in elections in Prussia until 1932. Otto Braun of East Prussia, who ruled almost uninterruptedly from 1920 to 1932 and is still regarded as one of the most capable Social Democratic politicians of the Weimar Republic, implemented together with his Minister of the Interior Carl Severing several pioneering reforms that were later exemplary for the Federal Republic. These included the ConstructiveVote of No Confidence, which made it possible to vote out the Prime Minister only if a new Prime Minister was elected at the same time. In this way, the Prussian state government could remain in office as long as no positive majority formed in the state parliament, i.e. a majority of those opposition parties that actually wanted to work together.

The Landtag election of 24 April 1932 also failed to produce a positive majority, as the radical parties KPD and NSDAP together received more mandates than all other parties combined. Because no coalition capable of governing was formed in parliament, the Braun government remained in office on a caretaker basis. This gave Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen the pretext for the so-called "Prussian coup". With this coup d'état, the Reich government deposed the Prussian state government by decree on July 20, 1932, under the pretext that it had lost control of public order (see also: Altona Bloody Sunday). Welcomed by most of the state apparatus, von Papen himself took power as Reichskommissar in Prussia, which until then had been able "to a certain extent [...] to live up to its role as a bulwark of Weimar democracy". The removal of the most important democratically-minded state government decisively facilitated Adolf Hitler's seizure of power six months later. The National Socialists thus had the Prussian government's means of power - above all the police apparatus - at their disposal from the very beginning.

| Results of the state elections 1919-1933 | ||||||||||||

| Year | 1919 | 1921 | 1924 | 1928 | 1932 | 1933 | ||||||

| Party | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats |

| SPD | 36,4 | 145 | 25,9 | 109 | 24,9 | 114 | 29,0 | 137 | 21,2 | 94 | 16,6 | 80 |

| Center | 22,3 | 94 | 17,9 | 76 | 17,6 | 81 | 15,2 | 71 | 15,3 | 67 | 14,1 | 68 |

| DDP/DStP | 16,2 | 65 | 5,9 | 26 | 5,9 | 27 | 4,4 | 21 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,7 | 3 |

| DNVP | 11,2 | 48 | 18,0 | 76 | 23,7 | 109 | 17,4 | 82 | 6,9 | 31 | 8,9 | 43 |

| USPD | 7,4 | 24 | 6,4 | 27 |

|

|

|

| ||||

| DVP | 5,7 | 23 | 14,0 | 59 | 9,8 | 45 | 8,5 | 40 | 1,5 | 7 | 1,0 | 3 |

| DHP | 0,5 | 2 | 2,4 | 11 | 1,4 | 6 | 1,0 | 4 | 0,3 | 1 | 0,2 | 2 |

| SHBLD | 0,4 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| KPD |

| 7,5 | 31 | 9,6 | 44 | 11,9 | 56 | 12,3 | 57 | 13,2 | 63 | |

| WP |

| 1,2 | 4 | 2,4 | 11 | 4,5 | 21 |

|

| |||

| Poland |

| 0,4 | 2 | 0,4 | 2 |

|

|

| ||||

| NSFP |

|

| 2,5 | 11 |

|

|

| |||||

| NSDAP |

|

|

| 1,8 | 6 | 36,3 | 162 | 43,2 | 211 | |||

| CNBL |

|

|

| 1,5 | 8 |

|

| |||||

| VRP |

|

|

| 1,2 | 2 |

|

| |||||

| DVFP |

|

|

| 1,1 | 2 |

|

| |||||

| CSVD |

|

|

|

| 1,2 | 2 | 0,9 | 3 | ||||

| The 100 % shortfall in votes was accounted for by groups not represented in parliament. | ||||||||||||

National Socialism and the End of Prussia (1933-1947)

After Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor, Hermann Göring became Reich Commissioner for the Prussian Ministry of the Interior. This meant that the executive power of the Prussian state government was at the disposal of the National Socialists when they came to power. A few weeks later, on 21 March 1933, the so-called Potsdam Day took place. On this occasion, the Reichstag, newly elected on March 5, was symbolically opened in the presence of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg in the Potsdam Garrison Church, the burial place of the Prussian kings. The propagandistic event, in which Hitler and the NSDAP celebrated "the marriage of old Prussia with young Germany", was intended to win over Prussian monarchist and German nationalist circles to the National Socialist state and to persuade the conservatives in the Reichstag to vote for the Enabling Act, which was due two days later.

From 1933 onwards, the Reich government created the National Socialist unitary state by means of Gleichschaltung laws. The Reich Governor Act of 7 April 1933 and the Act on the Reconstruction of the Reich of 30 January 1934 did not formally dissolve the Länder, but deprived them of their independence. All state governments were placed under the control of Reich governors. An exception to this was Prussia, where, according to the law, the Reich Chancellor himself was to exercise the "rights of the Reich Governor." However, Hitler transferred the exercise of these rights to the Prussian Prime Minister Göring by decree as early as 10 April 1933. At the same time, the (party) Gaue gained increasing importance for the implementation of national policy at the regional level. The Gauleiters were appointed by Hitler in his capacity as leader of the NSDAP. In Prussia, this anti-federalist policy went even further: since 1934, almost all of its state ministries had been merged with the corresponding Reich ministries. Only the Prussian Ministry of Finance, the archives administration and a few other state authorities remained independent until 1945.

The spatial extent of Prussia hardly changed between 1933 and 1945. In the course of the Greater Hamburg Act, even smaller territorial changes took place. Prussia was expanded on 1 April 1937 to include, among other things, the hitherto Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck. The Polish, formerly Prussian, territories annexed during the Second World War were for the most part not incorporated into neighbouring Prussia, but assigned to so-called Reichsgauen.

On 8 May 1945, the Second World War ended in Europe. With the subsequent occupation of the special area of Mürwik on 23 May, the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein was also completely occupied and the last Reich government located in the special area was arrested. After the end of National Socialist rule, Germany was divided into occupation zones and its eastern territories beyond the newly established Oder-Neisse border were incorporated into Poland and the Soviet Union. Thus the state of Prussia de facto ceased to exist in 1945. De jure it still existed until its formal dissolution by Control Council Law No. 46 of 25 February 1947, in which the Allied Control Council stated:

"The State of Prussia, which has always been the bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany, has, in reality, ceased to exist. Guided by the interest in maintaining peace and the security of the peoples and filled with the desire to secure the further restoration of political life in Germany on a democratic basis, the Control Council enacts the following law:

Article 1

The State of Prussia, its central government and all subordinate authorities are hereby dissolved."

- Allied Control Council on 25 February 1947

Even before the enactment of this law, Länder had been formed throughout the western occupation zone on territory that had previously been Prussian. After the decision of the Control Council, the dissolution of Prussia also continued in the Soviet occupation zone: The provinces of Saxony(-Anhalt) and Brandenburg, which until then had only existed as administrative units, were transformed into Länder, and the addition "Vorpommern" was removed from the name of the Land of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in 1947, so that in official usage, people from Greifswald, for example, were called "Mecklenburger". In the same way, inhabitants of the former Lower Silesian Upper Lusatia became "Saxons". At the same time, in the SBZ and later in the GDR, the use of the terms "Pomerania" and "Silesia" for the parts of these former Prussian provinces that remained German was officially considered undesirable.

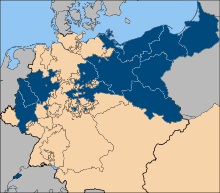

Prussia after the First World War (dark blue)

Otto Braun, the Social Democratic Prime Minister of the Free State of Prussia from 1921 to 1932

.svg.png)

Flag of the Free State of Prussia

.svg.png)

Standard of the King (1871-1918)

.jpg)

The Proclamation of the German Empire (18 January 1871) , oil painting by Anton von Werner, 1885

Prussia with its territorial gains from the German War of 1866 (dark blue) in the borders of the German Empire of 1871

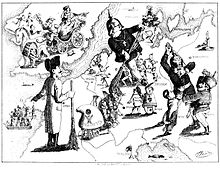

Round painting of Europe in August MDCCCXLIX , political cartoon by Ferdinand Schröder in the Düsseldorfer Monathefte, 1849: Prussia, personified as a military man in a pimple cap, "sweeps" out of Germany with a brush broom the Forty-Eighters, defeated in the German Revolution, who flee to Switzerland and embark for emigration to the New World.

Forcible dissolution of the Prussian National Assembly

Prussia after the Congress of Vienna 1815 (dark blue)

Rejoicing revolutionaries after barricade fights in Berlin, 18 March 1848

Prussian Landwehr Cavalry in the Wars of Liberation

Prussian residual state after the Peace of Tilsit 1807 (brown)

Queen Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1776-1810), popularly revered wife of Frederick William III and mother of Emperor William I.

Frederick II inspects potato cultivation on an inspection tour (oil painting The King Everywhere by Robert Warthmüller, 1886)

Prussia's territorial gains under Frederick II, 1740-1786 (green)

Replica of the coronation crown from 1701

Tobacco College of Frederick William I of Prussia (1736)

Edict of Potsdam 1685

Elector Frederick III crowns himself King Frederick I in Prussia, Königsberg 1701

The Great Elector at the Battle of Fehrbellin, 1675

Brandenburg-Prussia around 1700 (red and green) Map from F.W. Putzger's Historical School Atlas, 1905

Frederick I was the first Hohenzoller to take over the rule of the Mark Brandenburg in 1415.

This subsequently coloured map of Prussia from 1751 shows the ownership structure of Prussia as it existed between 1525 (creation of the Duchy of Prussia) and 1772 (First Polish Partition): the Duchy (later Kingdom) of Prussia and Pomerania are coloured yellow, and the royal Prussia under Polish sovereignty is coloured pink.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Prussia?

A: Prussia was a series of countries that originated in 1525. It was mostly used to refer to the Kingdom of Prussia, which was located in northern Europe and included land in Poland, France, and Lithuania.

Q: What are some different meanings associated with the name "Prussian"?

A: The name "Prussian" has had many different meanings over time. These include the land of the Baltic Prussians, lands of the Teutonic Knights, part of the lands of Polish Crown (Royal Prussia), a fiefdom of the Kingdom of Poland (Ducal Prussia), all Hohenzollern land inside or outside Germany, an independent Kingdom from 17th century until 1871, and finally as part of German Empire, Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany from 1871 to 1945.

Q: Where does the name "Prussia" come from?

A: The name Prussia comes from the Borussi or Prussi people who lived in the Baltic region and spoke Old Prussian language.

Q: How did Ducal and Royal Prussia relate to Poland?

A: Ducal Prussia was a fiefdom of the Kingdom of Poland until 1660 while Royal Prussia was part of Poland until 1772.

Q: What values were important for German-speaking prussians during late 18th century?

A: During late 18th century German-speaking prussians valued perfect organization, sacrifice (giving other people something you need) and obeying law.

Q: How did Chancellor Otto von Bismarck contribute to power dynamics between Germany and Northern Europe?

A: Chancellor Otto von Bismarck dissolved German Confederation which allowed him to annex almost all northern Germany into one state. In 1871 he created German Empire with Kings Of Prussia being Emperors Of Germany thus making it center point for power dynamics between Germany and Northern Europe.

Q: When did Allies abolish state Of prusssia ? A: Allies abolished state Of prusssia in 1947 , dividing its territory among themselves & new States Of germany .

Search within the encyclopedia