Reformation

Reformation (Latin reformatio "restoration, renewal") refers in a narrow sense to an ecclesiastical renewal movement that led to the division of Western Christianity into different denominations (Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed).

The Reformation started in the early 16th century from the two centres of Wittenberg and Zurich. Its beginning is generally dated to 1517, when Martin Luther is said to have posted his 95 theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg. Geneva developed into the third center of the Reformation in the 1540s, with Europe-wide influence. The Reformation came to an end within the Holy Roman Empire with the Peace of Augsburg (1555); outside the empire, however, developments continued into the 17th century.

The essential points of the Reformation, which are still the common denominator of the churches that emerged from the Reformation, are often expressed with the so-called exclusive particles, the four soli (Latin solus "alone"):

- sola gratia: It is by the grace of God alone that the believing person is saved, not by his works.

- sola fide: Man is justified by faith alone, not by good works.

- sola scriptura: Scripture alone is the basis of the Christian faith, not church tradition.

- solus Christus: The person, work and teaching of Jesus Christ alone can be the basis for man's faith and salvation.

The exclusive particles memorably formulate the central Reformation doctrines (justification and the Scriptural principle) from which all other theological doctrines are determined.

The Reformation movement was diverse from the beginning. Lutheranism emerged from the Wittenberg Reformation, and the Reformed church family, which includes Presbyterians and Congregationalists, emerged from the Swiss Reformation. The Anabaptist movement, which arose in the environment of the Swiss Reformation, pursued the restoration of the New Testament church of Jesus. Believer's baptism, which they practiced exclusively and which their opponents called rebaptism, was only a part and - strictly speaking - a consequence of their ecclesiology. Church for them was the community of believers in which social barriers had fallen. They practiced the priesthood of all believers and elected their elders and deacons in a "democratic" way. They advocated the radical separation of church and state, demanded religious freedom not only for themselves, and refused to take the oath in large parts of their movement. Above all, this made them suspect to the authorities, who could not accept their dissenting theological views so much as their criticism of the secular authorities and therefore resorted to harsh countermeasures and persecution. Among them today are the Mennonites, the Hutterites, and the Amish.

Anglicanism arose in England and Unitarianism in parts of Eastern Europe. The Reformation in Transylvania is regarded as a "special case of church history".

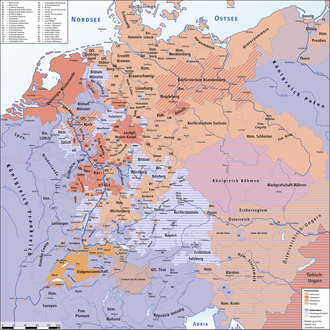

The Confessions in Central Europe around 1618

Explanation of terms

In the late Middle Ages, the Latin term reformatio denoted a return to an idealized order of the past, but also reform measures. The rebellious peasants took up the traditional reformatio term; in contrast, it is rarely found in Luther, Zwingli or Calvin. From the middle of the 16th century it became customary to refer to the now-deceased masterminds as reformers. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 brought the term ius reformandi, and reformed became a (controversial) denominational self-designation.

The term "Reformation" had the broader meaning of "reform" until the mid-19th century and has since been narrowed to the religious conflicts of the 16th century. Leopold von Ranke (German History in the Age of Reformation, 1839-1847) first treated the Reformation as a historical period. The fact that a multi-layered process was thus given the name of a historical epoch shows how strongly Protestant-dominated German historiography was in the early 19th century.

The Catholic church historian Hubert Jedin saw within the Roman Catholic Church a great reform movement from the late Middle Ages to the Enlightenment, in which he placed the Protestant Reformation, which he regarded as heresy and therefore put in inverted commas, as well as the Counter-Reformation.

Roland Bainton coined the term "left wing of the Reformation" in 1941 for groups such as the Anabaptist movement and the Spiritualists because they had been willing to make a more radical break with tradition. Because of the misleading political connotations, George Huntston Williams proposed the term Radical Reformation for these groups, which has become widely accepted in the English-speaking world.

Since the middle of the 20th century, the term "Second Reformation" has come to refer to the development of Reformed churches associated primarily with the name of Calvin. However, it poorly expresses the fact that the Swiss Reformation did not begin after the Wittenberg Reformation, but at about the same time as it.

Prerequisites

Humanism

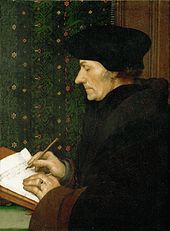

Humanism was an educational movement radiating from Italy since the 14th century, which advocated a revival of ancient scholarship. After the conquest of Constantinople (1453), Byzantine scholars had fled to Italy and given new impetus to the study of the Greek language and ancient authors. Renaissance humanists such as Erasmus of Rotterdam and Willibald Pirckheimer read works of Greco-Roman antiquity in the expectation of finding something valuable in them for personal life and social order. The church had emerged in this ancient context; and humanists assumed that pagan and Christian authors of the time were fundamentally complementary.

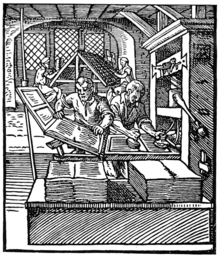

Letterpress

The history and the course of the Reformation are also media history, in which Luther, especially at the beginning, was also directly involved. For example, he distributed printing orders to various printers, examined the printing quality and often complained about poor results. By disseminating his writings, i.e. by making them public, Luther and his comrades-in-arms succeeded in bringing the theological discourse to a larger readership.

After book printing had become more and more widespread since the middle of the 15th century, there was a certain stagnation in publishing and printing around the turn of the century. This changed, among other things, due to the beginning of the Reformation: within a very short time, the circulation figures increased immensely. Thus, Pettegree (2016) and Pettegree and Hall (2004) saw the successful combination of book printing, the vernacular, the increased use of illustrations, such as from the workshop of Lucas Cranach, but also the decentralized distribution of printed matter as important pillars for the spread of Reformation ideas. While the existing or developing networks of letters were the central information exchange medium for humanist and Reformation content among the educated elite, print media opened these messages to an ever-widening circle of the literary readership. Luther had initially held back on print publications after assuming the Wittenberg professorship, lectura in biblia in 1512. It was not until unauthorized reprints of his "95 Theses on Indulgences," which had appeared in Nuremberg, Leipzig, and Basel after 1517, that there was apparently a change in publication strategy.

In 1520, at the height of Luther's publishing career, some 500,000 of his writings and pamphlets appeared on the market in the German-speaking world, although illiteracy was high at the time. It is estimated that only a little more than one million of the nearly twelve million inhabitants of the Holy Roman Empire could read. One of Luther's best-selling pamphlets, An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation (To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation), was published fifteen times in 1520, with up to 4,000 copies per edition.

In the context of the Reformation movement that started in Wittenberg, other authors also came to the fore. According to calculations, in 1524 alone, about 2,400 pamphlets were published with an estimated total of 2.4 million copies.

The spread of the Reformation was essentially based on the involvement of the vernacular readership. It learned of the entire development, starting with the criticism of indulgences and later to the church reform proposals, only when Reformation authors consciously addressed them with vernacular texts, especially with pamphlets. Thus, in the years 1518 to 1519, Luther had noticed that Latin and German-language texts reached two intellectually as well as socially different circles of recipients. He distinguished between scholars, by whom he understood Latin-literate people, especially theologians, and laypeople, who constituted by far the larger part of the subjects in the Holy Roman Empire and possessed at most vernacular reading skills.

Social and economic factors

The 16th century was marked by profound processes of social transformation. One reason for this was the increasing importance of the cities. Through trade, a middle class had formed in the cities that had considerable financial power. In this context, one also speaks of early capitalism. The patricians in the cities, e.g. the Fuggers in Augsburg, often surpassed with their economic power the rural nobility, who were engaged in agriculture. Agriculture was based on the work of the peasants, who formed the bulk of the population. They usually lived at the subsistence level and suffered from taxes, duties, indentured servitude and serfdom. In addition, the steady influx of precious metals from the Spanish colonies in America caused the value of money to fall (inflation). The purchasing power of the population fell, in some cases dramatically, so that economic historians speak of a "price revolution." In addition, the population grew. It is assumed that between 1500 and 1600 the population of the German Empire increased from 12 to 15 million. As a result of the population increase, food became more expensive while labor became cheaper. This socially and economically precarious situation led to repeated uprisings from the end of the 15th century, culminating in the German Peasants' War in 1525.

Political factors

Imperial Constitution

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation consisted of many individual territories, so it was not a centralized state like England or France. The emperor as the highest authority in the empire was elected by the seven electors (Mainz, Cologne, Trier, Saxony, Palatinate, Brandenburg, Bohemia), but had to grant them the preservation of their territorial rights in the so-called Electoral Capitulation. The highest legislative body of the empire were the imperial diets, which were convened by the emperor, usually when he needed money. The emperor could not pass laws on his own, but needed the approval of the Imperial Diet, where the electors, the high nobility in the Imperial Council of Princes, and the imperial cities were entitled to vote. For this reason, one speaks of dualism between the emperor and the imperial estates. This was a major factor in the spread of the Reformation. Due to the lack of a central authority in the empire, the fate of the Reformation was decided on a territorial level. This led to a confessional fragmentation of the empire, which the emperor wanted to prevent but could not because of his lack of power. Another reason was that in the first years after Luther's publication of the theses, Charles V was rarely in the empire and was busy with wars against France and the Ottoman Empire, so he could pay little attention to affairs in the empire. Moreover, the introduction of the Reformation was often in the interest of the individual sovereigns, who could thereby emancipate themselves from the emperor and the pope.

Political situation in Europe

In addition to the constitutional problems in the empire, there was the political situation in Europe. This was primarily shaped by the opposition between the Habsburgs and France. Emperor Charles V and the French King Francis I fought three Italian wars between 1521 and 1544, with only brief interruptions, for supremacy in Upper Italy and dominion over the Burgundian hereditary lands, to which both laid claim. The Habsburg Empire extended over the empire in central Europe, Spain (with southern Italy), and the Spanish colonies in the New World. France was embraced by two Habsburg territories. Charles V's goal was to link the empire to Spain by annexing southern France. Francis I wanted to prevent this at all costs. The Pope also feared Habsburg superiority and at times allied himself with the French king.

In addition, there was the constant threat of the Turks in southeastern Europe. In 1526 the Ottomans had defeated the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohács and in 1529 laid siege to Vienna, which was part of the Habsburg hereditary lands. The emperor was forced to raise money and troops to meet this threat. To do so, he needed the consent of the imperial estates, which weakened his position in the empire.

Due to his numerous obligations outside the empire, Charles V was abroad in 1521-1530 and 1532-1541. During this time, the Reformation was able to spread throughout the empire.

Religious factors

According to Berndt Hamm, the feeling of living in a time of crisis was widespread around 1500. The power of sin, death at any time and the expected severe judgment of God were constantly present as a sense of threat. People responded by seeking securities: "access to divine mercy, protection from the diabolical powers, preservation in the hour of death, salvation in judgment, and mitigation of the punishments of purgatory." Attractive were ideas of structuring the personal conduct of life and the organization of the polity consistently according to the commandments of God. The church, it was believed, administered the merits of Christ and the saints as a treasury of grace, and it provided opportunities to obtain God's forgiveness. It was recognized in this role in the late Middle Ages, more so than in other periods of church history. The bipolar model of externalization/internalization has been readily used in the history of research for the transition from the late Middle Ages to the Reformation period, which is not without problems.

Cathedral chapters and monasteries served to provide for the offspring of the sons of the nobility, who lived according to their status; the lower clergy adapted to the "lifestyles of their milieu" in the countryside, for example through concubinage or by running an inn. Characteristic of late medieval piety were endowments, masses for souls, pilgrimages, processions, and the acquisition of indulgences, which were intended to shorten the time in purgatory. All these services could be purchased from the church in exchange for money - a "fiscalization" of religion. This provoked criticism: on the one hand of the clerical proletariat, which lived more poorly than well from the masses for souls, and on the other hand of the lifestyle of the high clergy (bishops, canons), who accumulated benefices but delegated the duties associated with them without much concern for the pastoral care of the respective parishes. Hans-Jürgen Goertz uses the term "anticlericalism" as an explanatory model for the early phase of the Reformation because of this widespread criticism of the clerical class. Nicole Grochowina suspects a "participation crisis" of the laity, especially in the urban bourgeoisie, on the eve of the Reformation: the lifestyle of the clergy was no longer convincing; on the other hand, they continued to be privileged over the laity in their access to the sacred. Seen in this light, it was perhaps Luther's doctrine of the priesthood of all the baptized that won many people over to the Reformation (more than the Reformation doctrine of justification). It offered the possibility of taking responsibility for one's own salvation.

The reformers referred positively to actors of the 14th and 15th centuries, whom they regarded as precursors. According to their own perception, they had taken up and further developed their points of criticism and reform ideas:

- John Wyclif was a scholastic theologian who taught at Oxford University, where he emerged as a sharp critic of the church (especially 1372-78). The official church sought a heresy trial against him several times, but this failed. He lost his position at the university, however, and retired to Lutterworth as a country priest. Wycilf relativized the authority of the visible church, its hierarchy, and its sacraments. For him, belonging to Christ was shown in concrete acts of discipleship. To the king, he said, clergy also owed obedience. He called indulgences a "pious fraud" (pia fraus). With his doctrine of the Lord's Supper he met with massive opposition. For he rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation and taught that Christ was present in heaven as his own and in a spiritual way in the Eucharistic gifts, which he interpreted as an efficacious sign (signum efficiax). For Wyclif, the Bible was the law of God, Christ its messenger. He encouraged an English translation of the Bible. The Council of Constance condemned him posthumously as a heretic in 1415; his bones were exhumed and burned. His ideas lived on in England in the Lollarden movement and were communicated to Prague by Oxford students. Puritanism in particular referred to Wyclif as the "Morning Star of the Reformation".

- Jan Hus came into contact with the ideas of Wyclif at the University of Prague. Hus studied theology and became a professor at the university. He openly criticized the greed and secularization of the clergy and argued for a fundamental reform based on the Bible. He also did not recognize the Pope as the highest authority in matters of faith. Hus' criticisms were met with great popular acclaim, to the alarm of the Church. In 1408 he was deposed from his office and excommunicated in 1411, whereupon riots broke out in Prague. Hus continued to work as an itinerant preacher and drafted a doctrine of the church as a hierarchy-free community under the head Christ. In 1414 Hus was summoned before the Council of Constance, where he was to recant his statements. Against the promise of free passage by King Sigismund, Hus was burned as a heretic in 1415. Subsequently, numerous currents were formed which referred directly to Jan Hus and were therefore called Hussites. From 1419 to 1436 there were wars in Bohemia between these groups and the Bohemian king (Hussite Wars).

The Near Death: Dance of Death (1493)

Erasmus of Rotterdam

sixteenth-century printing

Charles V, c. 1548 as Holy Roman Emperor, Sacrum Romanum Imperium (from 1520 to 1556)

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Protestant Reformation?

A: The Protestant Reformation was a series of events that happened in the 16th century in the Christian Church. It was triggered by corruption in the Catholic Church, which led to some people trying to change how it worked. This resulted in a split between Catholics and various Protestant churches.

Q: Who were some of the key figures involved in the Protestant Reformation?

A: Key figures involved in the Protestant Reformation included Erasmus, Huldrych Zwingli, Martin Luther and John Calvin.

Q: When did The Ninety-Five Theses start the Protestant Reformation?

A: The Ninety-Five Theses started the Protestant Reformation in 1517 when they were posted at Wittenberg by Martin Luther.

Q: How did John Knox bring Luther's ideas to Scotland?

A: John Knox brought Luther's ideas to Scotland and founded the Presbyterian Church.

Q: What wars broke out because of different countries adopting Protestant ideas?

A: Wars broke out between Catholic and Protestant factions and countries due to different countries adopting Protestant ideas. These wars included the Thirty Years' War and Eighty Years' War, although they were not just about religion but also political disputes over state religions.

Q: How did recent inventions help spread awareness of abuses within the church?

A: Recent inventions such as printing presses helped spread awareness of abuses within the church by allowing for translations of Bibles into local languages like English (John Wycliffe & William Tyndale) or German (Martin Luther).

Q: What agreement ended religious wars between Catholics and Protestants?

A: The Peace of Westphalia ended religious wars between Catholics and Protestants by recognizing Protestants when signers agreed not to interfere with each other's internal affairs including chosen religion.

Search within the encyclopedia