Prison

This is the sighted version that was marked on June 6, 2021. There is 1 pending change that needs to be sighted.

![]()

This article discusses prisons as buildings; for the film of the same name, see Prison (1949).

A prison (in Austria also Kriminal) is any place where people are held against their will (cf. the definition of "places of detention" visited by the Committee for the Prevention of Torture). The term is therefore broader than that of correctional institution (in Germany), prison (in Austria) or penal institution (in Switzerland), which refers only to prisons used for the execution of justice, i.e. institutions for the placement of pre-trial and sentenced prisoners as well as persons in preventive detention.

In terms of construction, a prison generally consists of an extensive area with external protective facilities (fencing or wall with watchtowers) and, on the inside, buildings to accommodate the prisoners, the guard staff and social facilities. The open areas, which are easily visible, serve not only to allow prisoners to stay outside temporarily, but also to improve monitoring of the fence accesses.

A wall surrounds the prison building to prevent escapes.

Designations

Prison used to be an official term in German criminal law. Today, prisons in Germany are called correctional facilities; there, until the reorganization by the Great Criminal Law Reform in 1970, prison was officially a special kind of deprivation of liberty in contrast to, for example, penitentiary and workhouse.

In Switzerland, prisons are called penal institutions, correctional institutions or prisons, depending on the canton or function; in Austria, they are called correctional institutions. In Liechtenstein, the national prison is the only detention facility.

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment also uses the term place of detention.

Colloquially, prison stands for any kind of criminally prescribed deprivation of liberty. In addition, there are numerous other expressions, including mocking names: (der) Knast (from the Yiddish "knassen" for "punish"), (hinter) schwedische Gardinen, Café Viereck, (das) Kittchen, (hinter) Gitter, (im) Kahn und (im) Bau, in Austria also (der) Häfen, Zieglstadl, (der) Tschumpus or Gesiebte Luft (breathe). In Switzerland and Germany the prison is also called "Kiste". In former times, the prison was also called Büttelēy or Bütteley in some areas, because it was under the supervision of the Büttel, who often also had his apartment there.

History

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Prisons already existed in ancient times, but their function and significance differed greatly from today's prisons. In fact, the imprisonment of criminals played only a minor role in the catalogue of punishments until the beginning of modern times. Instead, a variety of different sanctions were imposed, such as fines, shameful punishments (pillories), banishment from the city (especially against vagrants and petty criminals), draconian corporal punishments (beatings, cutting off of limbs, blinding, cutting off of ears, ...) or death sentences (decapitation, hanging, burning, wheeling), which were usually carried out in public.

Imprisonment as a punishment in its own right basically did not exist; people were usually only locked up in prisons temporarily, either in the sense of pre-trial detention or until they received their actual punishment.

Primarily, therefore, prisons were used for security purposes, for example to hold defendants until the beginning of their trial or to hold convicts until the execution of their death sentence. A prominent example is Socrates, who spent the time until his execution in prison. A prominent detainee of Roman prisons is the apostle Paul, who suffered several prison terms under Roman officials, including about two years in Caesarea, to be interrogated over and over again until he was finally questioned in Rome by the emperor himself and ultimately sentenced to death. The Bible records this in places, as do ancient historians. Debtors were also imprisoned until they paid their creditors (see also debtors' prison). As late as the 19th century in England, up to 50 percent of the prison population consisted of debtors.

In the Middle Ages, prisons were often castle dungeons, cellars of town halls or towers that were part of the city walls (hence the expression "türmen" for a prison break). Another form of deprivation of liberty outside prisons was forced labor, such as in mines or on galleys. With the discovery of new continents at the beginning of the early modern period, criminals were also exiled overseas to the newly founded colonies.

Prisons were not infrequently places of torture, which was used, for example, in the times of the Inquisition to force confessions. Death sentences imposed on heretics could in some cases (such as when the accused recanted) be commuted to life imprisonment.

early modern period

It was not until the late 16th century that the first forerunners of modern prisons in the form of workhouses and penitentiaries emerged in many European countries. One of the first institutions of this kind was the workhouse at Bridewell Castle, established by Edward VI at the instigation of the Anglican Church in 1555. In 1555 at the instigation of the Anglican Church. It became the model for similar workhouses, often called "bridewells" in English-speaking countries. In the Netherlands, the Amsterdam Tuchthuis (penitentiary) was established in 1596. It was one of the models for the Schallenhaus, the first prison in Switzerland, founded in 1615. However, a large proportion of the inmates of workhouses and penitentiaries were not criminals, but mainly beggars and vagrants, i.e. social fringe groups who caused offence in public.

The Reformation had changed society's relationship to poverty: Whereas poverty had once been considered a God-given fate that had to be alleviated through almsgiving, Calvinism in particular saw poverty as self-inflicted. In the course of the moral renewal of the Reformation, society also focused more on combating vice. Therefore, penitentiaries were, as it were, "moral prisons" in which drunkards, prostitutes and adulterers were also imprisoned and were supposed to mend their ways through hard work and religious instruction.

From the end of the 16th century, numerous penitentiaries were established in Germany: in Nuremberg in 1588, in Bremen in 1609, in Lübeck in 1613, in Hamburg in 1622, in Danzig in 1629, in Frankfurt in 1679, in Munich in 1682, and in Berlin in 1712. Often workhouses and penitentiaries were run by families who lived off the cheap labor of the inmates as well as public subsidies. Workhouses for women were often called "spinning houses" because they were mainly used for weaving, spinning and sewing clothes.

In the course of time, the penitentiaries developed more and more into "normal" prisons, in which actual criminals were also locked up. At the same time, the prisons, which often had to finance themselves, became more and more dilapidated in the 17th and 18th centuries. The numerous death and corporal punishments had been increasingly criticized as a result of the Reformation and later the Enlightenment, which had led to a decline in these punishments. Prisons were seen as a humane alternative, but this led to increasing overcrowding.

18th and 19th century

The first comprehensive critique as well as reform proposals for the prison system were proposed by the English Calvinist John Howard: in 1773 he became High Sheriff of Bedfordshire, as such he was also responsible for the local prisons. Howard was appalled by the conditions there, but his complaints to the higher authorities had no effect. In the years that followed, Howard made many trips throughout Britain and Europe, visiting numerous prisons. In 1777, he published The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, in which he described the prisons of the time as "... cesspool, school for criminals, brothel, gambling den, and liquor house, except an institution in the service of criminal law and crime."

Howard called for prisons to be reformed in key ways:

- Meaningful work for prisoners and fair remuneration

- Fight against laziness, gambling and alcohol

- Healthy diet

- Hygienic conditions due to the installation of bathrooms, etc.

- A tiered prison system in which prisoners can gain prisoner relief through good behavior.

- solitary confinement to prevent criminal infection

- Sufficient payment of the guards

- Regular inspections of prisons by the supervisory authorities

Many of Howard's proposals were taken up and implemented by the English legislature in the course of time. In Germany, Howard's ideas were spread primarily by the Protestant institutional clergyman Heinrich Balthasar Wagnitz.

Parallel to Howard, there were also prison reforms in the United States, which were, among other things, a model for reforms in Germany. Important impulses came from the Quaker religious community, which demanded the abolition of death sentences and beatings and drew attention to abuses in prisons. Pennsylvania was a Quaker stronghold, and in 1787 the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons was founded here. In 1821, it enforced the construction of the Eastern State Penitentiary, where the prisoners were to find their way back to a life with God according to the religious ideas of the Quakers.

This was to be achieved through strict isolation: The prisoners were housed in solitary cells, were not allowed to communicate with each other and only received visits from prison chaplains. The only permitted reading was the Bible. The prisoners were supposed to achieve repentance and conversion in solitude. Charles Dickens, who had visited the prison in 1842, criticized the "Pennsylvania system" as "cruel and wrong."

The Eastern State Penitentiary was one of the first prisons of panopticon design, in which cells (wings) are grouped radially around a center (see #Bauweise von Gefängnissen). In 1848 the first German prison in panopticon design was opened in Bruchsal, followed by Berlin-Moabit in 1849.

Unlike the "solitary system" in the Eastern State Penitentiary, the "silent system" applied in Auburn State Prison in New York, which opened in 1818: the prisoners were not allowed to communicate with each other, but were not isolated for this purpose. Instead, they were threatened with corporal punishment for the slightest infraction. Only at night were they housed in single cells; during the day they had to work together. In the USA, the "Auburn system" prevailed for most prisons.

In 1842, Pentonville Prison was opened in London on the model of the Eastern State Penitentiary. Here the multi-level "progressive system" applied: only at the beginning of their sentence did prisoners have to be held in solitary confinement, after which they could ascend or descend three levels of lighter confinement depending on their behaviour and could also be released earlier if they behaved well.

Michel Foucault located the development of the modern prison between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries: while it was still common in the 18th century to brutally execute criminals in public, this practice almost disappeared only a century later. In its place was a complex, systematic, and total prison system that hid delinquents and their suffering from public view. "Punishment has gradually ceased to be a spectacle," Foucault states for the early 19th century.

Development in Germany

In Prussia, corporal punishment was largely replaced by imprisonment after the introduction of the Prussian Land Law of 1794. Inspired by developments in England and the USA, the Prussian Ministry of Justice drafted the "General Plan for the Introduction of a Better Criminal Court Constitution and for the Improvement of Prisons and Penal Institutions" in 1804. This was based on the following basic principles:

- Distinction between reformable offenders and incorrigible criminals

- separation of pre-trial and trial detention

- first approaches of a graduated penal system

- Emphasis on education and improvement

- Work as the preferred method of education

- Support after discharge

At the beginning of the 19th century, the first private prison societies and prisoner welfare associations were founded, for example Theodor Fliedner's "Rheinisch-Westfälische Gefängnisgesellschaft". These societies, most of which were religiously motivated, were intended to provide educational opportunities and religious renewal for prisoners and those released from prison.

After the unification of the Reich, the Reich Penal Code came into force in 1871, which provided for four types of imprisonment:

- Penitentiary with compulsory labour (1 year to life)

- Prison with right to work (1 day to 5 years)

- Fortress Prison

- Workhouse for vagrancy, drunkenness, work-shyness, professional fornication (up to 2 years)

Fortress imprisonment was a previously existing prison sentence for members of the higher classes: Politicians, officers, and nobles guilty of misdemeanors were sometimes imprisoned in guarded rooms that could be quite comfortable.

The prison system was scientifically examined in the 19th century by the Hamburg physician Nikolaus Julius, among others, who lectured in the 1840s on the subject of "Prison Science or on the Improvement of Prisons". The jurist Franz von Liszt advocated a gradual system of imprisonment and distinguished three essential goals of prisons ("Marburg Programme" of 1882):

- Rehabilitating offenders who are able and willing to improve their situation

- Deterring offenders who are unwilling to reform.

- Custody of offenders who are not capable of improvement

Weimar Republic and National Socialism

In 1923, the states of the Weimar Republic agreed in the Reichsratsgrundsätze that the penal system should no longer be subject to deterrence and retribution. Dark confinement and beatings as a means of discipline were abolished. Prisoners were classified and the execution of sentences proceeded in stages.

This development was abruptly reversed in 1933 after the National Socialists came to power: Now the penal system was again primarily oriented towards retribution and deterrence. The prisons filled up, among other things because of several tightenings of criminal law and the introduction of new offences. While fines decreased, imprisonment increased, and death sentences became much more common. Concentration camps developed in parallel with the regular prison system, but the boundaries between the two systems became increasingly blurred during the Nazi era. Especially against political prisoners arbitrariness prevailed.

Postwar period to present

The prisons of the post-war period were often overcrowded, the staff unqualified. With the introduction of the Basic Law in 1949, the death penalty was abolished in the FRG. In 1957, the sentence of probation was introduced. In 1970, the Great Criminal Law Reform abolished the various custodial sentences such as penitentiary etc. and introduced a uniform custodial sentence, which was now executed in correctional institutions. Until 1977, the penal system in the Federal Republic was regulated only by administrative regulations. This changed with the Prison Act (Strafvollzugsgesetz, StVollzG), which came into force in 1977: prisons were now primarily to serve the purpose of resocialisation, which is why life in prison was to be largely brought into line with living conditions outside prison. In addition, the harmful effects of deprivation of liberty were to be reduced.

Particularly with regard to the idea of resocialisation, there are currently various forms of mitigated prison sentences and open prison: in the latter, prisoners only spend the night in prison and can go to their family and pursue their work during the day. In this way, the prisoner remains socially integrated. Another variant is the "leisure sentence", which is used in Switzerland and the Netherlands: It provides that prisoners only have to go to prison on weekends.

The Swiss jurist Benjamin F. Brägger sees a humanisation of the penal system from the Middle Ages to the present day, which is not yet complete: "Just as the custodial sentence once pushed back the death and corporal punishments, we are now in a phase in which new, non-custodial sanctions are increasingly limiting the use of the custodial sentence, even replacing it. We need only briefly mention community service, electronically monitored house arrest, or criminal mediation."

Eastern State Penitentiary (1855)

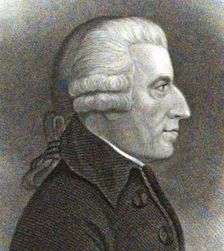

John Howard (1726-1790)

Women prisoners processing hemp in Bridewell Prison (William Hogarth, 1732)

Schuldturm in Nuremberg: towers that belonged to the city wall were often used as prisons

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a prison?

A: A prison is a building where people are forced to live if their freedom has been taken away, usually as punishment for breaking the law.

Q: How do people end up in prison?

A: People can end up in prison after being convicted of a crime in court and receiving a prison sentence. They may also be held in pre-trial detention or remand before their trial. In times of war, captured soldiers may become prisoners of war and civilians may be placed in an internment camp. In some countries, prisons are also used for political prisoners (people who disagree with the country's leader or government).

Q: Are there different kinds of prisons?

A: Yes, there are different kinds of prisons depending on the country and region. In the US, "jails" are run by local governments and hold people who have not yet had their trial or who have been convicted for a minor crime. US "prisons" or "penitentiaries" are run by state or federal governments and hold people who are serving long sentences for serious crimes. Outside of North America, "prison" and "jail" mean the same thing.

Q: What happens to inmates' possessions when they enter prison?

A: Inmates have most or all their personal possessions confiscated until release when they enter prison in developed countries such as the United States. They must wear prison uniforms while incarcerated as well.

Q: Is there slang for prisons?

A: Yes, there is slang for prisons such as gaol (pronounced like jail) or correctional facility.

Q: Are jails and prisons different things in the US?

A: Yes, jails and prisons mean separate things in the US - jails are run by local governments and hold people who have not yet had their trial or who have been convicted for a minor crime; whereas prisons/penitentiaries are run by state or federal governments and hold people serving long sentences for serious crimes

Search within the encyclopedia