Printing press

![]()

This article deals with the mechanical printing press. Colloquially, any other form of printing machine is also called a printing press.

A printing press is a mechanical press used to transfer an image, usually text, onto a substrate by means of an inked printing forme, resulting in an impression. Widely considered the most significant event of the second millennium AD, the invention and spread of the printing press revolutionized the field of communication and information and, as a transmitter and multiplier of knowledge and ideas, significantly ushered in the world epoch of early modernity.

This letterpress printing process was developed around 1440 in the Holy Roman Empire by Johannes Gutenberg from Mainz; Gutenberg modified existing techniques such as the screw press and combined them with his own groundbreaking inventions to create a closed printing system. With the help of his specially created hand-casting instrument, movable type could be produced quickly and accurately in large quantities for the first time, a prerequisite for the economic viability of letterpress printing as a whole.

The mechanization of the art of printing using the letterpress led to the first mass production of books in history. A single printing press at the time of the Renaissance could print 3,600 pages in a working day, compared to forty by hand printing and a few by copying; works by intellectual or secular authorities such as Luther or Erasmus were sold by the hundreds of thousands during their lifetimes.

Starting from a single town, Mainz in Germany, knowledge of printing spread to over two hundred towns in a dozen countries in Europe within just a few decades. By 1500, printing presses scattered throughout Western Europe had already produced over 20 million printed works. As the new printing technology became more widespread, total production increased tenfold in the course of the 16th century to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies. The upkeep of a printing press went hand in hand with the operation of a printing press to such an extent that the name of the device was transferred to the new media branch of the press. As early as 1620, the English statesman and philosopher Francis Bacon wrote that the printing press had given things a new face all over the world.

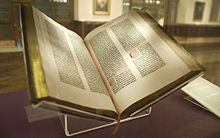

Since its beginnings, book printing has also been considered and practiced as an art form, dedicated to high aesthetic and artistic standards, such as in the famous Gutenberg Bible. Today, incunabula are among the best-kept treasures of great libraries.

The unprecedented influence of letterpress printing in the wake of Gutenberg on the long-term development of the history of Europe and the world is difficult to grasp in its entirety. Analytical approaches include the idea of a genuine printing revolution and the emergence of a Gutenberg galaxy. The wide availability of the printed word at affordable prices promoted the education of the masses and laid the foundation for the emergence of the modern knowledge society.

In Renaissance Europe, the printing press with movable type heralded the age of mass communication, which was accompanied by a profound process of social change: Relatively unhindered access to information and (revolutionary) ideas overcame state borders, gripped the masses in the Reformation, and threatened the time-honored power position of political and religious elites; the steep rise in the literacy rate broke the monopoly of the literate upper class on intellectual formation and education and strengthened the right of the aspiring middle class to have a say. Printing was not limited to books; any information could be disseminated on printed paper. Across the continent, the growing cultural self-confidence of the peoples led to the emergence of proto-nationalism, which was given additional impetus by the gradual displacement of Latin as the lingua franca in favour of the vernacular languages.

Numerous detailed improvements to printing presses were invented and used. The 19th century saw the transition to industrial mass production with the introduction of steam-driven and later electrically driven printing presses, as well as the invention of the high-speed cylinder press and rotary presses. Printing presses and machines spread all over the world and Western letterpress technology became the basis for the mass printing of our time.

Columbia press from 1820, exhibited in the DASA in Dortmund

Stanhope press from 1842

Printing press from 1811, exhibited in Munich

History

Economic conditions and intellectual climate

See also: Medieval University

The rapid economic and socio-cultural development at the end of the Middle Ages provided favorable conditions for Gutenberg's invention: The entrepreneurial spirit of early capitalism promoted economic thinking in business life and encouraged the rationalization of the traditionally artisanal mode of production. The demand for books increased due to the growing need for education and the increasing spread of the ability to read in middle-class circles to such an extent that the traditional, time-consuming method of copying by hand could no longer meet the demand. In this situation, the decentralized state of the late medieval world opened up a certain amount of room to advance individual solutions without intervention from political and religious authorities.

Technical factors

See also: History of typography

At the same time, the development of a number of medieval products and technical processes had progressed to the point where their use for printing purposes became potentially interesting. Gutenberg's merit is to have recognized these widely scattered products and processes in their value for letterpress printing, to have brought them together into a complete and functioning printing system, and to have perfected them through a number of his own fundamental inventions and innovations:

The screw press allows direct pressure to be applied to a flat surface. Introduced by the Romans in the 1st century AD, it already had a long history of diversification in Gutenberg's time: As a winepress, it was common in both Mediterranean and medieval agriculture for extracting juice from grapevines and oil from olive pits and other oil seeds. Very early on, screw presses were also used in the urban textile trade as cloth presses. Gutenberg may also have been inspired by the paper presses that became widespread in the German lands from the late 14th century onwards and worked on the same mechanical principle.

By adopting the basic design for his printing press, Gutenberg was able to mechanize the printing process, a crucial prerequisite for the mass production of printed works. However, printing placed different demands on the machine than pressing out. Gutenberg adapted the design so that the platen exerted a pressure on the paper that was both uniform and springy. To speed up the whole process, he introduced a flat and movable lower table on which the sheets could be changed quickly.

The idea of movable type was not entirely new in the 15th century; sporadic references to knowledge of the typographic principle have appeared in Europe since the 12th century at the latest. Medieval examples of typographic text production, i.e. the continuous reuse of letters to create an entire text, range from Germany (Prüfeningen consecration inscription) to Italy (Pilgrim II's altarpiece) and England (letter bricks). However, the practical suitability of the various techniques (stamps, hallmarks and the stringing together of individual letters) was too limited to become widely accepted.

Gutenberg succeeded in decisively improving the printing process by establishing typesetting and printing as two separate work steps. A goldsmith by trade, he cast his letter metal from a lead alloy that proved so suitable for letterpress printing that it is still used today. The mass production of metal letters was made possible by his key invention of a special hand-casting instrument that was excellently suited for the rapid reproduction of identical types. The use of the Latin alphabet was an enormous advantage, as it allowed the typesetter to reproduce any text using only about two dozen letters and various punctuation marks.

Another important factor that had a favourable effect on the emergence and spread of printing was the codex format in which books had been published since Roman times. In a centuries-long process that is considered the most significant development in the history of the book before the invention of printing itself, the codex had completely replaced the ancient scroll by the beginning of the Middle Ages (around 500 AD). The codex has considerable practical advantages over the scroll: it is more convenient to read (by turning pages), more compact, less expensive, and above all, unlike the scroll, recto and verso can be used for writing and printing.

A fourth development was the rapid mechanization of medieval papermaking. The introduction of water-powered paper mills, which are securely attested from 1282, enabled European papermakers to greatly expand production, displacing the laborious manual work common in China and the Muslim world. The number of papermaking centres rose steeply in the late 13th century in Italy, where the price of paper fell to one-sixth that of parchment, and fell still further; about a hundred years later the first paper mills also began operating in Germany.

Nevertheless, the final breakthrough of paper as a writing medium seems to have been no less dependent on the rapid spread of printing with movable type. In this context, it is revealing that parchment codices, whose quality as a writing material is considered unsurpassed, still made up a substantial part of Gutenberg's edition of the 42-line Bible. Only after numerous attempts did the Mainzer succeed in overcoming the difficulties that the conventional water-based inks caused by wetting the paper, and in finding a composition for an oil-based printing ink that was suitable for high-quality printing with metal type.

A paper codex of the much-lauded B-42, Gutenberg's magnum opus.

Early modern wine press. Screw presses of this type were used in the craft and agricultural sectors for many purposes and served Gutenberg as a model for his printing press.

Course at a medieval university in the 14th century

Letter sorted into a set box and clamped in an angled hook

Gutenberg Press

→ Main article: Johannes Gutenberg and platen printing press

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a printing press?

A: A printing press is a machine used to print books, newspapers and other documents. It uses separate alloy letters screwed into a frame which are then moved over paper and ink, leaving an impression of the letters in the form of text or illustrations.

Q: How was woodcut printing done?

A: Woodcut printing involved whole pages being cut into wood with words and pictures.

Q: Who improved the process in the 15th century?

A: Johannes Gutenberg improved the process in the 15th century by using separate alloy letters screwed into a frame.

Q: What was this process called?

A: This process was called typesetting.

Q: What two ideas altered the design of the printing press entirely during industrial revolution?

A: During industrial revolution, two ideas altered the design of the printing press entirely - firstly, using steam power to run machinery; secondly, replacing flatbeds with rotary motion of cylinders.

Q: Who designed a machine for hot metal typesetting?

A: Linotype Inc designed a machine for hot metal typesetting which turned molten lead into type ready for printing.

Q: How has cost of printing changed compared to other commodities over time?

A: The cost of printing has fallen significantly compared to other commodities due to inventions such as steam power and cheaper paper production from wood pulp instead of rags. Nowadays, price of books or magazines are less determined by their production costs and more by factors such as marketing.

Search within the encyclopedia