Polio

![]()

This article is a redirect from polio. It describes spinal polio. For cerebral palsy, see Infantile cerebral palsy.

Poliomyelitis (from Greek πολιός 'grey', μυελός 'marrow'), often called polio for short, German (spinal) polio, polio disease or Heine-Medin disease, is an infectious disease caused by polioviruses, mainly in childhood. It affects motor neurons and can lead to severe, permanent paralysis. This often affects the extremities. Infestation of the respiratory muscles is fatal; in response, this disease process led to the development of the first machine ventilation techniques. Even years after infection, the disease can recur.

The virus is usually transmitted by smear infection (urine or stool), but droplet infections are also possible. It can only replicate in humans (and some species of monkeys) and can only be transmitted from person to person.

Vaccines against polio have been available since the 1950s. Since then, the number of cases has fallen sharply. Major health organizations, led by the WHO, have been working for years to eradicate polio. The only infectious diseases specifically eradicated by humans in modern times are smallpox and rinderpest. However, there are always setbacks. For example, two children in Ukraine fell ill in 2015, even though Europe was declared completely polio-free in 2002. Currently, polio is spreading in Afghanistan and Pakistan. After four years without a new case of wild poliomyelitis in Africa, the WHO declared Africa "wild polio-free" on 25 August 2020.

Independent of wild polioviruses, so-called live vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) circulate in Africa, a consequence of unimmunized or underimmunized populations with low hygienic standards. As a result, on September 1, 2020, WHO assessed the risk of spread of cVDPVs in Central Africa and the Horn of Africa as "high." More than a dozen countries in Africa, including Angola, Congo, Nigeria and Zambia, continue to fight the disease.

Occurrence

Children between the ages of three and eight are predominantly affected; only occasionally do adults also fall ill. There is no causal treatment for this viral disease. Due to consistent vaccination, polio is now officially considered "eradicated" in Germany.

Poliomyelitis was first described clinically in the 18th century by the English physician Michael Underwood (1736-1820). The disease was described in more detail by the Black Forest orthopaedic surgeon Jakob Heine, who in 1840 published a book entitled Observations on paralytic conditions of the lower extremities and their treatment. What he described he called spinal polio in the second edition of 1860. The Swedish physician and researcher Karl Oskar Medin (1847-1927), who recognized the epidemic character of the disease, followed up on Heine's findings. Hence the further designation of polio as Heine-Medin disease.

According to current knowledge, poliomyelitis existed as an endemic disease until 1880. It was not until around 1880 that this infectious disease appeared in epidemic form, affecting thousands of people every year. Children in particular died from it or suffered permanent physical sequelae. From about 1910 onwards, regional epidemics occurred in Europe and the United States every five to six years. Among the best-known victims was the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who significantly promoted research for a vaccine during his presidency. The introduction of virus culture by J. F. Enders in 1952, thanks to which Jonas Salk developed an inactivated (dead) vaccine in 1954, is regarded as an advance in research into a vaccine. This, however, was insufficiently effective. The live attenuated vaccine developed by Albert Sabin made polio control possible from 1960. As a result, the number of polio cases fell from several 100,000 per year to about 1,000 per year.

In 2010, a severe outbreak occurred in Tajikistan, which also spread to Russia. On 5 May 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared poliomyelitis outbreaks in Cameroon, Pakistan, and civil-war-torn Syria, and the spread from there to Equatorial Guinea, Afghanistan, and Iraq, an "extraordinary event" that required urgent coordinated action to prevent a global resurgence of the disease.

In early September 2015, WHO reported two cases of polio in children in southwestern Ukraine. There is a high risk of the disease spreading there. In that country, only 50% of children are vaccinated against polio. Because of better vaccination rates, there is little risk to neighboring Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia. In August 2019, Nigeria became the last African country to be officially declared poliomyelitis-free. Globally, new cases are reported in the endemic Afghanistan and Pakistan. There were 33 cases there in 2018, and these were joined by 72 new cases in Pakistan in 2019 (as of early October).

Man with atrophied leg due to poliomyelitis

Pathogen

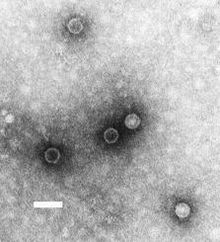

The causative agent of this disease is the poliovirus. It is an unsheathed virus with single-stranded RNA of positive polarity (ss(+)RNA) of approximately 30 nanometers in diameter, belonging to the genus Enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae. Three serotypes are known: Type 1 ("Brunhilde"), which is considered the most paralytic and tends to spread epidemically; it was named after a chimpanzee named Brunhilde who was infected at the time. In addition, there are type 2 ("Lansing") as well as type III ("Leon"), which have not been detected for years and have since been declared eradicated by the WHO. There is no cross-immunity between the three types of pathogen. This means that an infection with one of the three types does not protect against a further infection with one of the other two types. In addition to humans, a few great apes are also infected, and transmission in humans occurs through other humans.

Poliovirus under the electron microscope

Search within the encyclopedia