Plato

![]()

Plato is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Plato (disambiguation) and Plato (disambiguation).

Plato (ancient Greek Πλάτων Plátōn, Latinized Plato; b. 428/427 bc in Athens or Aigina; † 348/347 bc in Athens) was an ancient Greek philosopher.

He was a pupil of Socrates, whose thought and method he portrayed in many of his works. The versatility of his talents and the originality of his seminal achievements as a thinker and writer made Plato one of the best known and most influential figures in the history of ideas. In metaphysics and epistemology, in ethics, anthropology, the theory of the state, cosmology, the theory of art, and the philosophy of language, he set standards even for those who - like his student Aristotle - contradicted him on central issues.

He saw the literary dialogue, which allows the course of a joint investigation to be understood, as the only appropriate form of the written presentation of philosophical endeavors for truth. Based on this conviction, he helped the still young literary genre of the dialogue to achieve a breakthrough and thus created an alternative to didactic writing and rhetoric as familiar means of presentation and persuasion. In doing so, he incorporated poetic and mythical motifs as well as craft contexts in order to convey his thought processes in a playful, descriptive manner. At the same time, with this way of presenting his views, he avoided dogmatic determinations and left many questions that arose open or left their clarification to the readers, whom he wanted to stimulate to their own efforts.

A core theme for Plato is the question of how undoubtedly certain knowledge can be obtained and distinguished from mere opinions. In the early dialogues, he is primarily concerned with using the Socratic method to show why conventional and common ideas about what is worth striving for and what is the right thing to do are inadequate or useless, enabling the reader to trace the step from supposed knowledge to admitted ignorance. In the writings of his middle creative period, he tries to create a reliable basis for real knowledge with his doctrine of ideas. Such knowledge, according to his conviction, cannot refer to the always changeable objects of sense experience, but only to incorporeal, unchanging and eternal realities of a purely spiritual world, inaccessible to sense perception, the "ideas", in which he sees the primordial and model of sense things. To the soul, whose immortality he wants to make plausible, he ascribes participation in the world of ideas and thus an access to the absolute truth existing there. Whoever turns to this truth through philosophical efforts and completes an educational program geared to it can recognize his true destiny and thus find orientation in central questions of life. Plato sees the task of the state in creating optimal conditions for the citizens for this and in implementing justice. Therefore, he deals intensively with the question of how the constitution of an ideal state can best serve this goal. In later works, the doctrine of ideas partly recedes into the background, partly problems arising from it are critically examined; in the field of natural philosophy and cosmology, however, to which Plato turns in his old age, he assigns a decisive role to the ideas in his explanation of the cosmos.

Plato founded the Platonic Academy, the oldest institutional school of philosophy in Greece, from which Platonism spread throughout the ancient world. Plato's intellectual legacy influenced numerous Jewish, Christian, and Islamic philosophers in a variety of ways. His most important disciple was Aristotle, whose school of thought, Aristotelianism, grew out of critical engagement with Platonism. In late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the early modern period, Aristotelianism became the starting point for concepts that partly competed with Platonic ones and partly merged with them.

In modern times, thinkers of the "Marburg School" of Neo-Kantianism (Hermann Cohen, Paul Natorp) in particular exploited Platonic thought. Karl Popper attacked Plato's political philosophy; his accusation that it was a form of totalitarianism triggered a long-lasting controversy in the 20th century.

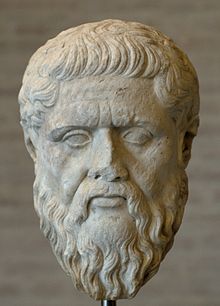

Roman copy of a Greek portrait of Plato, probably by Silanion and placed in the Academy after Plato's death, Glyptothek Munich

Complete editions and translations

Plato's works are still cited today according to the page and section numbers of the edition by Henricus Stephanus (Geneva 1578), the so-called Stephanus pagination.

Total editions without translation

- John Burnet (ed.): Platonis opera. 5 vols. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1900-1907 (critical edition; reprinted several times).

- Platonis opera. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1995 ff. (authoritative critical edition; replaces Burnet's edition, but so far only volume 1 has appeared).

- Volume 1, ed. by Elizabeth A. Duke et al, 1995, ISBN 0-19-814569-1.

Translations (German)

Friedrich Schleiermacher's translation, which appeared in Berlin between 1804 and 1828 (3rd edition 1855), is still widely used in German-speaking countries today and is reprinted - sometimes in a somewhat altered form.

- Otto Apelt (ed.): Plato: Sämtliche Dialoge. 7 vols., Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (without Greek texts; reprint of the Leipzig 1922-1923 edition).

- Gunther Eigler (ed.): Plato: Works in Eight Volumes. 6th, unchanged edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2010 (1st edition 1970-1983), ISBN 978-3-534-24059-3 (critical edition of the Greek texts; slightly edited translations by Schleiermacher).

- Plato: Jubiläumsausgabe sämtlicher Werke, introduced by Olof Gigon, transferred by Rudolf Rufener, 8 volumes, Artemis, Zurich/Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 (without Greek texts).

- Ernst Heitsch, Carl Werner Müller, Kurt Sier (eds.): Plato: Werke. Translation and Commentary. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen from 1993 (without Greek texts; various translators; 22 volumes published so far).

- Helmut von den Steinen: Platonica I. Cleitophon, Theages. An introduction to Socrates. Edited by Torsten Israel. Queich-Verlag, Germersheim 2012, ISBN 978-3-939207-12-2 (metrically formed, scenically designed artistic transmission; further volumes not yet published).

Translations (Latin, medieval)

- Plato Latinus, ed. Raymond Klibansky, 4 vols. London 1940-1962 (vol. 1: Meno, interprete Henrico Aristippo; vol. 2: Phaedo, interprete Henrico Aristippo; vol. 3: Parmenides ... nec non Procli commentarium in Parmenidem, interprete Guillelmo de Moerbeka; vol. 4: Timaeus a Calcidio translatus commentarioque instructus).

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Plato?

A: Plato was one of the most important classical Greek philosophers who lived from 427 BC to 348 BC.

Q: How wealthy was Plato?

A: Plato was a wealthy man, owning at least 50 slaves.

Q: What did Plato create?

A: Plato created the first university school, called "The Academy".

Q: Who was Socrates and what is his relation to Plato?

A: Socrates was a student of Plato (who did not write) and the teacher of Aristotle.

Q: What did Alfred North Whitehead say about philosophy since Plato?

A: Alfred North Whitehead said that all philosophy since Plato has just been comments on his works.

Q: What ideas in philosophy did Plato write about? A: Plato wrote about many ideas in philosophy such as deductive reasoning which are still talked about today.

Q: What university did Aristotle found? A: Aristotle founded another university known as the Lyceum.

Search within the encyclopedia