Avery Brundage

Avery Brundage [ˈeɪvri ˈbrʌndɨdʒ] (* September 28, 1887 in Detroit, Michigan; † May 8, 1975 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany) was a U.S. sports official, entrepreneur, patron of the arts, and track and field athlete. From 1952 to 1972 he was the fifth and to this day only non-European president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). He is best remembered as an unyielding advocate of amateurism in sport and for his controversial role in connection with the 1936 and 1972 Summer Games.

Brundage came from a working-class family in Detroit. When he was five years old, the family moved to Chicago, where his father left his family. Raised primarily by relatives, Brundage studied engineering at the University of Illinois, where he was also successful as an athlete. He competed in the 1912 Olympics, finishing sixth in the pentathlon. Between 1914 and 1918, he became U.S. champion three times. After graduation he founded a construction company, through which he achieved prosperity.

After his active sports career ended, Brundage quickly gained influence as a sports official in various associations. He strongly opposed a boycott of the 1936 Summer Games, which had been awarded to Berlin before the NSDAP seized power. Although Brundage managed to get a US delegation sent there, their participation remained controversial to this day. In the same year he was elected to the IOC and immediately became one of the most influential members of the Olympic movement.

Brundage's election as IOC president followed in 1952. In this capacity, he rigorously pursued violations of amateurism and opposed any commercialization of the Olympics, even as his views became increasingly out of step with the realities of modern sport. His last Games as president in 1972 were overshadowed by the Munich Olympic assassination. Brundage denounced the politicization of sport and refused to cancel the Games ("the Games must go on") - a stance that drew criticism in various circles. As a private citizen, Brundage was a collector of Asian artworks, and his donations founded the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

Brundage (1964)

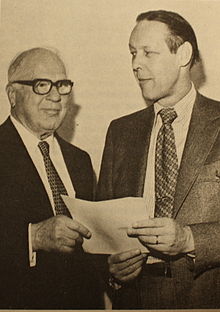

Brundage (left) with John Corbally, president of the University of Illinois, at the announcement of the Avery Brundage Fellowships (1974).

Brundage's signature

Youth and athletics career

Born in Detroit, Avery Brundage was the son of Charles Brundage and his wife Amelia, née Lloyd. The family moved to Chicago when he was five years old. His father, a stonemason, left the family soon after. Avery and his younger brother Chester were raised primarily by aunts and uncles. In 1901, as a 13-year-old, Avery Brundage won an essay contest and was allowed to travel to the second inauguration of President William McKinley. In Chicago, he attended Sherwood Public School and then R.T. Crane Maual Training School, a technically oriented high school. Before taking public transportation in the morning to make the eleven-mile trip to school, he delivered newspapers. Although the school had no athletic facilities, Brundage made his own sports equipment in the school workshop, including a bullet for shot put and a hammer for the hammer throw. In his senior year, newspapers wrote about Brundage, a future track star. According to a 1980 Sports Illustrated article by sportswriter William Oscar Johnson, Brundage was "the kind of man who would have been immortalized by Horatio Alger - the battered and deprived American street kid who rose to flourish in the company of kings and millionaires."

In 1905, after graduating from high school, Brundage enrolled at the University of Illinois, where he mastered an arduous program of engineering courses. Four years later, he graduated with honors. He wrote articles for various student publications and was an active athlete. Brundage played basketball and was a member of the varsity track team; in addition, he participated in various other school sports. In his senior year, he was a major contributor to the University of Illinois track and field championship in the Western Conference, beating, among others, the University of Chicago, coached by Amos Alonzo Stagg.

After graduation, Brundage worked for three years as a site manager for the leading architectural firm Holabird & Roche. During that time, he oversaw the construction of $7.5 million worth of buildings, which was three percent of the total construction in Chicago at the time. Brundage disliked corruption in Chicago's construction industry; his biographer Allen Guttmann points out that the young engineer was in a position that would have allowed him to profit from influence-his uncle Edward J. Brundage led the Republican Party on Chicago's North Side and later served as Attorney General of the State of Illinois. Avery Brundage successfully competed in various track and field events. In 1910, as a member of the Chicago Athletic Association (CAA), he placed third in the American all-around championships (the forerunner of today's decathlon) and continued to train in preparation for the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm.

In his only Olympic Games appearance, Brundage finished sixth in the pentathlon and 22nd in the discus throw. In the decathlon he was far behind the leaders after eight events and dropped out of the competition, something he always regretted later. In the pentathlon, he moved up one place after Olympic champion Jim Thorpe was disqualified. Thorpe had played baseball for money and thus was not considered an amateur. Throughout his tenure as IOC president, Brundage refused to rehabilitate his countryman. The IOC did not do so until 1982, after the deaths of both men. Brundage's refusal led to accusations that he held a grudge because he had been beaten in Stockholm.

Back in Chicago, Brundage took a job as a site manager for John Griffith and Sons Contractors. Among the buildings he worked on for Griffith were the Cook County Hospital, the Morrison Hotel, the Monroe Building, and the National Biscuit Company warehouse. In 1915 he went into business for himself and founded the Avery Brundage Company, of which his uncle Edward was a director (see also the "Contractors" chapter). Brundage continued his athletic career. In 1914, 1916, and 1918, he became the U.S. all-around champion. Later, he began playing American Handball and was one of the top ten players in the country. In 1934, at the age of already 46, he won one of two games against Angelo Trulio, who had been national champion shortly before.

Brundage at the all-around championships 1916 in Newark (New Jersey)

Sports Official

Growing influence

As his athletics career drew to a close, Brundage began to work as a sports official - first with the CAA, then with the Central Amateur Athletic Association (of which the CAA was a member), and from 1919 with the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). The AAU contended with the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) for supremacy in amateur sports in the United States. The athletes themselves suffered most from this dispute, as the two associations threatened to suspend anyone who competed in the rival organization's events. Another source of conflict was the US National Olympic Committee, then called the American Olympic Committee (AOC). This AAU-dominated organization was originally convened only once every four years, just before and during each Olympic Games, to nominate athletes and move them to the venue. In 1920, there was an éclat when the AOC rented a disused troop carrier to bring home the American team from the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. But most team members preferred to book passage on an ocean liner. In response, the AAU formed the American Olympic Association (AOA), which operated between the Games and determined the members of the AOC. In 1928, after the resignation of then AOA president Douglas MacArthur, Brundage succeeded him. He was also elected president of the AOC; a post he held for over 20 years.

In 1925, Brundage was elected vice president of the AAU and chairman of the American Handball Committee. After a year as 1st Vice President, he was elected President in 1928. He held this position until 1935 (with the exception of a one-year hiatus in 1933). In this position he succeeded in reaching an agreement between NCAA and AAU. The former was awarded the right to certify college students as amateurs and was able to provide more representatives on the AOA's executive board.

Brundage quickly exhibited behavior that sportswriter Roger Butterfield called "dictatorial temperament" in a 1948 article in Life magazine. In 1929, track star Charles Paddock stated that Brundage and other officials used him as a spectator attraction to make money for the AOC while treating him poorly. In turn, Brundage accused Paddock of spreading falsehoods and engaging in "sensationalism of the worst kind." Paddock eluded Brundage's influence by turning to professional sports. Soon after track and field athlete Mildred Didrikson won three medals at the 1932 Summer Games in Los Angeles, she appeared in an automobile advertisement and the Brundage-led AAU summarily suspended her amateur status. Didrikson objected that she had not been paid at all and that the rules for maintaining amateur status were too complex anyway. In his first of numerous conflicts with female athletes, which have been played out through the media, Brundage countered that he himself had never had any problems with the rules when he had been an Olympic athlete, adding, "You know, the ancient Greeks kept women out of their athletic contests. They wouldn't even let them on the sidelines. I'm not entirely sure, but I think they were probably right." According to Butterfield, Brundage distrusted female athletes because he suspected some of them were men in disguise. Brundage litigated and lost for the American Olympic Committee against the 1932 Games organizing committee, claiming a share of the Games' surplus. However, the court ruled that the organizing committee did not have to give anything because it alone had borne the financial risk of the games.

Olympic Games 1936

Fight against a boycott

In May 1931, the IOC had awarded the 1936 Summer Games to the German capital Berlin. Several IOC members pointed out that with this step they would support the democratic government, which was coming under increasing pressure from the political extremes due to the world economic crisis. However, after the Reichstag elections on July 31, 1932, implementation appeared uncertain. The NSDAP, led by Adolf Hitler, had become the strongest party and initially showed little interest in international sport. Instead, it preferred "German games" so as not to have to compete against what it considered "inferior races" such as Jews, Slavs and people of African origin. After the National Socialists seized power on January 30, 1933, there were considerations to award the Olympic Games elsewhere.

The Nazis distrusted Theodor Lewald, the chairman of the organizing committee, because he had a Jewish father (his aunt Fanny Lewald was a prominent Jewess), but soon recognized the propaganda potential of the Olympic Games. Lewald had intended to run the Games on a modest budget; now, however, the resources of the state were being poured into the venture. In the face of massively rising anti-Semitism, there were repeated calls for the Olympics to be awarded to another country or boycotted. As a leading member of the Olympic movement in the United States, Brundage received numerous letters and telegrams urging him to act. A broad coalition, which gave rise to the Fair Play Movement, questioned the adherence to and respect for the Olympic Charter and demanded equal opportunities for all participants, regardless of denomination or race. The IOC tried to meet these demands. In 1933, IOC President Henri de Baillet-Latour wrote to Brundage: "I personally do not like the Jews and their influence, but I will not allow them to be molested in any way." According to historian Christopher Hilton, "Baillet-Latour and those around him had no idea what was coming, and if the German [IOC] delegates were continually giving them assurances, what were they to do but accept them?" Baillet-Latour was opposed to a boycott, as was Brundage, who had learned in 1933 that he was being considered for IOC membership. According to Carolyn Marvin, Brundage's political worldview was shaped by the notion that communism was an evil beside which all other evils were insignificant; he had admired Hitler for pushing back communism and restoring prosperity and order in the German Reich.

Assurances by the National Socialists that there was no discrimination in sport stood in stark contrast to their actions, which included in particular the exclusion of Jews from sports clubs. In September 1934, Brundage traveled to Germany to assess the situation. He met with government officials, but was allowed to speak with Jewish representatives only when accompanied. At a meeting in the Hotel Kaiserhof he asked the Jewish delegation whether Jews could become members of German sports clubs. When this was answered in the negative, he replied that "in my club in Chicago Jews were not admitted either". Since he assumed that just as in the USA Jews had their own sports clubs, he could not see any discrimination. Upon his return, Brundage reported, "I received written assurance ... that there would be no discrimination against Jews. One cannot ask for more than that, and I think the guarantee will be fulfilled." Brundage's trip only fueled controversy over the issue of American participation. Congressman Emanuel Celler suggested that Brundage had already made up his mind before leaving America. Regardless, on September 26, 1934, based on Brundage's report, the AOC approved the motion to send a U.S. team to Berlin.

Given the widespread discrimination, it seemed increasingly obvious that no Jew would make the German Olympic team. Brundage commented that so far only just twelve Jews had represented the German Reich and it would therefore hardly be surprising if none at all did so in 1936. Boycott advocates turned their attention to the AAU after the AOC's negative decision. They hoped that this organization, though also presided over by Brundage, would not nominate athletes for Berlin. At the December 1934 AAU meeting, there was no vote on a boycott; Brundage did not seek re-election and the delegates elected Jeremiah T. Mahoney as the new president. The boycott issue temporarily faded into obscurity, but reports of new discrimination against Jews in June 1935 rekindled sentiment, whereupon Mahoney also advocated a boycott. In October 1935, Baillet-Latour urged the three American IOC members, William May Garland, Charles H. Sherrill, and Ernest L. Jahncke, to do everything in their power to ensure U.S. participation. While Garland and Sherrill agreed, Jahncke refused and announced he would support a boycott. At the request of Baillet-Latour, Brundage led the anti-boycott campaign. At the AAU convention on December 8, 1935, delegates finally agreed to participate by a vote of 58 to 56; Brundage had postponed the vote for a day in order to achieve a result agreeable to him with additional delegates who had been summoned. The victorious Brundage called on some of his opponents to resign. Not all complied, but Mahoney did.

Brundage believed the boycott controversy could be used effectively for fundraising. He wrote of it, "The fact that the Jews are against us will arouse the interest of thousands of people who have never been involved before, if properly approached." In March 1936, he wrote advertising mogul Albert Lasker (a Jew) complaining that "a large number of misguided Jews still insist on interfering with the activities of the American Olympic Committee. The result, of course, is increased support by the 120 million gentiles in the United States, since this is a patriotic endeavor." In another letter, which David Large calls "heavy-handed," Brundage felt that by financially supporting American participation in the Olympics, Jews could reduce anti-Semitism in the United States. Lasker did not respond to this blackmail, replying to Brundage: "You gratuitously insult not only Jews but the millions of patriotic Christians in America in whose name you dare to speak without authority and whom you so tragically misrepresent in your letter." He appealed to the American public with a campaign pamphlet, Fair Play for American Athletes, to help fund the sending of teams to Germany.

In Berlin

On July 15, 1936, the U.S. contingent of athletes and officials, led by Brundage, embarked in New York. Immediately after arriving in Hamburg, Brundage made headlines when he and the AOC expelled swimmer Eleanor Holm (1932 Olympic champion in the 100-meter backstroke) from the team for misconduct aboard the Manhattan. There were conflicting rumors and reports about Holm's activities. For example, she was said to have "pulled an all-nighter" with screenwriter Charles MacArthur (who was traveling without his wife, actress Helen Hayes). Brundage discussed the matter with other AOC members and confronted Holm. After unsuccessfully asking to be readmitted, she remained in Berlin as a journalist, even though the AOC tried to send her home. A few years later, Holm claimed that Brundage had suspended her for rejecting him when he made an indecent proposal to her. According to Guttmann, Brundage has always had a reputation for being a "killjoy" ever since. Butterfield goes on to list, due to the efforts of sportswriters who accompanied Holm, Brundage "became famous as a bully, a snob, a hypocrite, a dictator, and a bore," as well as "pretty much the meanest man in the whole sports world."

On July 30, 1936, six days after the U.S. team arrived in Germany, the IOC met in Berlin and unanimously excluded Jahncke because of his support for the boycott movement. Two seats were vacant for the United States because Sherrill had died in June, but the minutes specifically record that Brundage was elected in place of Jahncke.

The U.S. 4-by-100-meter relay team originally included Sam Stoller and Marty Glickman, two Jewish athletes. After Jesse Owens won his third of four gold medals, they were removed from the lineup and replaced by Owens and Ralph Metcalfe. Coach Lawson Robertson justified this by saying that the Germans had strengthened their team. The relay team set a world record in both the prelims and the final, finishing well ahead of the Italians and the Germans in each event. Neither Stoller nor Glickman (the only Jews on the track team) believed their coach's reasoning. Stoller suspected favoritism because the two other relay runners, Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff, were coached at the University of Southern California by Dean Cromwell, an assistant to Robertson. Glickman thought anti-Semitism was more likely, and in later years was convinced that Brundage had ordered the exchange because "he and Cromwell sympathized with the Nazis." After Stoller's death in 1998, then USOC Chairman William J. Hybl said, "I was a prosecutor. I'm used to examining evidence. The evidence was there." What the evidence was, however, he left open. In his final report, Brundage called the controversy "absurd." He pointed out that Glickman and Stoller had finished 5th and 6th, respectively, in the preliminaries in New York and that the relay victory had vindicated the decision.

The road to the IOC presidency

Brundage's first IOC session as acting member was in June 1937 in Warsaw. IOC Vice-President Godefroy de Blonay had died, and Sigfrid Edström of Sweden took his place. Brundage in turn took over Edström's position on the executive board. In the fight against the boycott, Edström had been Brundage's ally. He had written to him that while he did not wish to see the Jews persecuted, as an "intelligent and unscrupulous people" they should have been "kept within certain limits." To a German correspondent, Brundage wrote that he regretted that Leni Riefenstahl's documentary Olympia could not be shown commercially in the U.S. "because the cinemas and film companies are almost all owned by Jews."

The Berlin Games had increased Brundage's admiration for the German Reich. In October 1936, at an American Federation event in Madison Square Garden, he said, "Five years ago they [the Germans] were discouraged and demoralized-today they are united-sixty million people who believe in themselves and in their country ..." In 1938, his construction company was awarded a contract to build a new German embassy in Washington, D.C., but this could not be carried out because of World War II. Brundage joined the Keep America Out of War Committee and became a member of the America First Committee. He resigned from both organizations the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The 1940 Olympic Games were cancelled due to the war. Brundage strove to organize games in the western hemisphere as a kind of substitute. In August 1940, he attended a sports congress in Buenos Aires where the possibility of holding Pan-American Games was discussed. Upon his return, he made arrangements to rename the AOA the United States of America Sports Federation. This in turn would organize the United States Olympic Committee (as the AOC would be renamed), as well as another committee that would be responsible for American participation in the Pan American Games. Brundage was one of the first members of the international Pan-American Games Commission; the staging of the first Games in Buenos Aires was delayed until 1951. Despite his role in their creation, Brundage viewed the Pan-American Games as an imitation, with no real connection to antiquity.

The war fractured the IOC geographically and politically. Baillet-Latour was stuck in German-occupied Belgium, while Brundage and Vice-President Edström did their best to keep the lines of communication open between IOC members. According to Guttmann, Brundage and Edström considered themselves "guardians of the sacred flame, protectors of an ideal in whose name they were ready to take action again as soon as the madness ended." Baillet-Latour died in January 1942; Edström then assumed presidential duties, although he continued to call himself vice president. He and Brundage did not wait for the war to end to rebuild the Olympic movement. Brundage even sent aid packages to IOC members in places in Europe where food was scarce. In 1944, given his advanced age, Edström expressed concern about who would lead the IOC in the event of his death and suggested that a 2nd Vice President position be created for Brundage. A postal vote of those IOC members who could be reached confirmed the appointment the following year. When Edström was elected president in Lausanne in September 1946 at the first IOC session of the post-war period, Brundage moved up as 1st vice-president.

As vice-president Brundage belonged to a commission set up in 1948 by the IOC session in London to examine whether the 1906 Olympic Intermediate Games held in Athens should be recognized as fully-fledged Olympic Games. All three members of what later became known as the Brundage Commission were from the Western Hemisphere and met in New Orleans in January 1949. The Commission concluded that there would be no advantage in recognizing the 1906 Intermediate Games; such a move could possibly set an embarrassing precedent. The IOC adopted the report when it met in Rome that same year.

Edström intended to resign after the 1952 Summer Games in Helsinki. Brundage's rival for the presidency was the Briton Lord Burghley (later Marquess of Exeter), Olympic champion in the 400 metres hurdles in 1928 and president of the IAAF. The election took place at the IOC session before the Games in the Finnish capital. Although Brundage was the executive candidate, he was met with disapproval by some IOC members, while others preferred a European president. Notes written during the vote revealed that Brundage only prevailed over Lord Burghley on the 25th ballot by 30 votes to 17.

Brundage around 1941

Brundage (left) with other officials and Captain Leopold Ziegenbein aboard the Bremen, en route to the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch, Germany

From left to right: Julius Lippert, Avery Brundage and Theodor Lewald in Berlin (1936)

Search within the encyclopedia