Philosophy

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Philosophy (disambiguation).

Philosophy (ancient Greek φιλοσοφία philosophía, Latinized philosophia, literally "love of wisdom") attempts to fathom, interpret, and understand the world and human existence.

Philosophy differs from other scientific disciplines in that it is often not limited to a specific field or methodology, but is characterized by the nature of its questions and its particular approach to its diverse subject matter.

This article deals with Western (also: occidental) philosophy, which originated in ancient Greece in the 6th century BC. It does not deal with the traditions of Jewish and Islamic philosophy, which have a manifold connection with Western philosophy, or with the traditions of African and Eastern philosophy, which were originally independent of it.

In ancient philosophy, systematic and scientifically oriented thinking developed. In the course of the centuries, the various methods and disciplines of understanding the world and the sciences differentiated themselves directly or indirectly from philosophy, in part also in demarcation from irrational or religious world views or myths.

The core areas of philosophy are logic (as the science of logical thinking), ethics (as the science of right action) and metaphysics (as the science of the first reasons of being and reality). Other basic disciplines are epistemology and philosophy of science, which deal with the possibilities of gaining knowledge in general and specifically with the ways of knowledge of the various individual sciences.

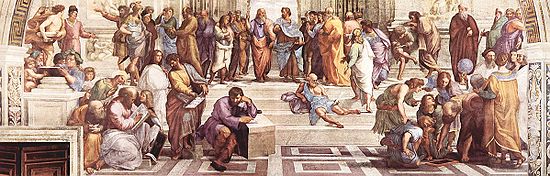

Raphael's School of Athens with the idealized representations of the founding fathers of Western philosophy. Although since Plato primarily a matter of written treatise, animated conversation remains an important part of philosophical life to this day.

Term History

The term "philosophy", composed of Greek φίλος (phílos) "friend" and σοφία (sophía) "wisdom", literally means "love of wisdom" or simply "knowledge" - for sophía originally denoted any skill or expertise, including craftsmanship and technology. The verb philosophize first appears in the Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC) (I,30,2), where it is used to describe the thirst for knowledge of the Athenian statesman Solon (c. 640-559 BC). That Heraclitus already used the term philósophos is not to be assumed. In antiquity, the introduction of the term philosophy was attributed to Pythagoras of Samos. The Platonist Herakleides Pontikos handed down a story according to which Pythagoras is supposed to have said that only a god possesses true sophía, and that man can only strive for it. Here sophia already means metaphysical knowledge. The credibility of this report by Herakleides - which has been handed down only indirectly and in fragments - is disputed in research. Only in Plato do the terms philosopher and philosophizing clearly appear in the sense intended by Herakleides, especially in Plato's dialogue Phaedrus, where it is stated that the pursuit of wisdom (philosophizing) and the possession of wisdom are mutually exclusive and that the latter belongs only to God.

Throughout its history, philosophy has been defined as the pursuit of the good, the true and the beautiful (Plato) or of wisdom, truth and knowledge (Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley). It searches for the highest principles (Aristotle) and aims at the acquisition of true knowledge (Plato). It strives for the knowledge of all things, including the invisible (Paracelsus), is the science of all possibility (Wolff) and of the absolute (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel). It orders and connects all science (Kant, Mach, Wundt), represents the "science of all sciences" (Fechner). The analysis, processing and exact determination of concepts is at its centre (Socrates, Kant, Herbart). At the same time, however, philosophy is also the art of learning to die (Plato), the normative teaching of values (Windelband), the rational pursuit of happiness (Epicurus, Shaftesbury) or the pursuit of virtue and efficiency (Aristotle, Stoa).

From a European perspective, the term philosophy is associated with its origins in ancient Greece. The Asian traditions of thought (Eastern philosophy), which are also thousands of years old, are often overlooked or underestimated. Religious worldviews also belong to philosophy, insofar as their representatives do not argue theologically, but philosophically.

History

→ Main article: History of philosophy

The history of Western philosophy begins in the 6th century BC in ancient Greece. One of its essential characteristics is that new answers to basic philosophical questions have been found, justified and discussed again and again. This can be attributed partly to changing needs of the prevailing spirit of the time, partly to the continuing development of the other sciences. "Progress" in the sense of a definitive refutation or proof of doctrines, however, is hardly made by philosophy in the view of some philosophers. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once characterized the history of European philosophy since Aristotle as mere "footnotes to Plato." Since philosophical ideas and concepts do not become obsolete, the study of its own history is of far greater importance to philosophy than to most other sciences.

enlarge and show information about the picture

![]()

Epochs and currents in the history of philosophy in a chronological overview

Ancient

→ Main article: Philosophy of antiquity

In the cities of ancient Greece, cultural advances and increased contact with neighboring cultures led to growing criticism of the traditional worldview, which was shaped by myth.

It was in this intellectual climate that the history of Western philosophy began with the Presocratics - as the Greek philosophers before or during the lifetime of Socrates are known. Their thought, which has only survived in fragments, is determined by natural philosophical questions about the foundations of the world. By means of a mixture of speculation and empirical observation they tried to understand nature and the processes within it. They wanted to trace all things back to an original principle (Greek ἀρχή arché), and specifically an "original substance". Thus the first known philosopher Thales of Miletus considered water to be this "primordial substance". Empedocles founded the doctrine of the four elements water, fire, earth and air, of which all things are composed, which prevailed in natural philosophy until the 18th century.

In addition to these approaches, there were other models of explaining the world. Pythagoras and his school considered number to be the all-determining principle and thus anticipated an important principle of modern natural science. Heraclitus emphasized becoming and passing away and saw the logos, a unifying principle of opposites, as the basis of reality. The philosophy of Parmenides, who, in contrast, assumed the unity and imperishability of being, is seen as the beginning of ontology.

With the appearance of the Sophists in the middle of the 5th century, man became the focus of philosophical consideration (Protagoras: "Man is the measure of all things"). They were particularly concerned with ethical and political problems, such as the question of whether norms and values are natural or determined by humans.

The Athenian Socrates (469-399 BC) became a model of European philosophy. His method of maieutics ("midwifery") consisted of Socrates, in apparent naivety, pointing out contradictions in his interlocutors' thinking by means of a profound and purposeful questioning technique and leading them to insights ("assisting them in giving birth") that helped them to a philosophically changed view of the world. His demonstrative intellectual independence and non-conformist behavior earned him a death sentence for impiety and corrupting the young (cf. Apology).

Since Socrates himself did not record anything in writing, his image has been largely determined by his disciple Plato (ca. 428-347 BC), in whose work Socrates is of central importance. This work, written largely in dialogue form, forms a central starting point for Western philosophy. Starting with the Socratic what-is question ("What is virtue? Justice? The good?"), Plato created the beginnings of a doctrine of definition. In addition, he was the originator of a doctrine of ideas, which is based on the idea of a two-part reality: The material object, which can be perceived by the sense organs, is opposed on the level of ideas by an abstracted, general correspondence accessible only to the intellect receptive to it. According to Plato's conviction, knowledge of these ideas leads to a deeper understanding of the whole of reality.

Plato's student Aristotle (384-322 BC) rejected the doctrine of ideas as an unnecessary "doubling of the world". For him, the essence of a thing consisted not in an additionally existing idea, but in the form inherent in the thing. His school began to divide, analyze, and scientifically order all of experiential reality-nature and society-into distinct branches of knowledge. Aristotle also founded classical logic (syllogistics), science systematics and philosophy of science. In doing so, he introduced basic philosophical concepts that remained authoritative until modern times.

At the transition from the 4th to the 3rd century BC, two further philosophical schools emerged in Hellenism in Athens, which placed individual salvation at the centre of their endeavours with a clear shift in emphasis compared to the Platonic Academy and the Aristotelian Peripatos: For Epicurus (c. 341-270 BC) and his followers, on the one hand, and for the Stoics around Zeno of Kition, on the other, philosophy served mainly to achieve psychological well-being or serenity by ethical means. Epicurus envisaged a moderately structured, well-dosed life of pleasure, which kept away from all political activity. The Stoics sought peace of mind by maintaining equanimity in the face of all internal and external challenges. This was to be achieved primarily through control of the emotions in conjunction with a fate-affirming attitude in harmony with the order of the universe; at the same time, one was aware of one's obligations to one's fellow men and to the community. This teaching later found its way into leading circles of the Roman Republic.

While the followers of the Pyrrhonian skepticism basically denied the possibility of certain judgments and unquestionable knowledge, Plotinus reshaped Plato's doctrine of ideas in the 3rd century (Neoplatonism). His conception of the gradation of being (from the "One" down to matter) offered Christianity manifold possibilities and was the predominant philosophy of late antiquity.

Medieval

→ Main article: Philosophy of the Middle Ages

The philosophy of the Middle Ages separated itself only gradually from theology and even then remained essentially shaped by religious institutions, ways of life and doctrines. In terms of method and content, it was strongly oriented towards traditions and authorities. In the Christian context, the foundation and reference point were essentially the teachings created by the Patristic Fathers of the Church.

Until the beginning of the late Middle Ages, the views of Augustine of Hippo proved to be decisive. He understood world history as an incessant struggle of the kingdom of evil against the kingdom of good. Society and church, theology and philosophy thus form a unity that leaves no room for doubt about decisions made by the church.

The "last Roman" and "first scholastic" Boethius stood at the beginning of the medieval attempts to form a synthesis between Platonic and Aristotelian thought, founded medieval logic, formed concepts such as "person" or "nature", triggered the universal controversy and drafted a momentous conception of science to which, for example, the School of Chartres followed.

While in the East the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire preserved important parts of ancient knowledge, the fragmentary preservation of the ancient heritage in the "Latin West" was largely confined to the monastic and cathedral schools until the beginning of the late Middle Ages. By 1100, only a few philosophers had emerged, including Anselm of Canterbury, who formulated a purely philosophical proof of God that was to have a lasting after-effect.

Since the late 11th century, Western philosophy experienced an upswing. The dissemination of translated works by Arabic-speaking philosophers, who in turn drew on ancient traditions, played an essential role.

One of the main topics of medieval philosophy early on became the Universalienstreit. This concerned the question of whether general concepts are mere mental abstractions and conventions for the purpose of understanding or whether they denote an independent objective reality, as the Platonic tradition asserts with its doctrine of ideas. In connection with this problem area, many thinkers dealt intensively with the logic of language; the "speculative grammar" arose, which asks for the connection between a theory of grammar and a theory of reality. Many philosophers took mediating positions in the universal controversy, among them Petrus Abaelardus. The latter contributed much to the formation of the scholastic method of contrasting and weighing opposing doctrines.

In the 13th century, numerous works of Aristotle previously unknown in the West became accessible in new translations; to these were added the writings of the Arabic-language commentators on Aristotle. They became the basis of university teaching. Especially Albertus Magnus and his student Thomas Aquinas ensured the spread of Aristotelianism, which eventually prevailed over the hitherto dominant Platonism and Augustinianism, respectively, and remained the authoritative philosophical direction in the academic world until deep into the early modern period. Thomas founded Thomism, a large-scale attempt to merge Aristotelian philosophy with the teachings of the Catholic Church. While the Dominican order was an early adopter of this initially condemned conception, Franciscan thinkers such as John Duns Scotus in particular devised alternatives. Among other things, he recognized the autonomy of philosophy over theology. For him, the object of metaphysics was not God (Averroes), but being as being (Avicenna). Furthermore, he insisted on the difference between the believed God and the God conceived within the framework of philosophy, which made numerous purely philosophical methods of proof - for example, for the immortality of the soul - impossible.

Concepts in which intellectual knowledge was aimed not at the general but at the individual made it possible to establish an experience-oriented science, as another precursor of scientific thought, Roger Bacon, also called for: by turning away from speculation and faith in authority. Another precursor of modernism was the most prominent champion of nominalism, William of Ockham, who blazed a new trail in philosophy in the early 14th century (via moderna). Marsilius of Padua founded a new theory of the state, in which important ideas of the modern era (social contract, separation of church and state) were announced.

The most important representative of Christian mysticism in the Middle Ages was Meister Eckhart, who saw himself as a "life master" and emphasized the importance of the practical implementation of philosophical knowledge in one's own life. Also in this tradition was Nicholas of Cusa, who on the threshold of modern times anticipated many developments of the following centuries. His ideas, ranging from the unknowability of God to the laws and limits of physics or cognition, point ahead to later thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein.

early modern period

→ Main articles: Philosophy of the Renaissance and Humanism and Philosophy of the Modern Era

The transition from the Middle Ages to modern times is marked by the Renaissance and humanism. In this epoch, alongside the broad current of traditional scholasticism, modern philosophy was gradually established.

Political philosophy in particular was set in motion during the Renaissance: Niccolò Machiavelli's thesis that the exercise of political rule should not be judged from a moral but solely from a utilitarian point of view still causes offence today. Thomas More took a completely different direction in his utopia (Utopia, 1516), in which he outlined a state with education for all, with religious freedom and without private property, thus anticipating some of the ideas of modernity.

While the humanist Pico della Mirandola attempted to demonstrate a fundamental agreement between all philosophical traditions, the thinking of men such as Johannes Kepler, Nicolaus Copernicus or Giordano Bruno was determined by the attempt to combine philosophy and the natural sciences. Ideas such as the heliocentric view of the world, that of the infinite cosmos or the belief in all-gods met with fierce resistance from the Church.

The scientific view of the world, the methods of mathematics and the belief in reason determined the philosophy of the modern era in the 17th and 18th centuries. In theory, it anticipated the political upheavals that then culminated in the French Revolution.

The world explanation of rationalism is based on "reasonable conclusions", thus also the Cartesianism founded by René Descartes (1596-1650). His sentence "I think, therefore I am", with which he believed to have found the indubitable origin of all certainties, is one of the most famous philosophical theses. Thinkers such as Spinoza and Leibniz developed his approach further in great metaphysical system designs (cf. Monad). This epistemological approach was applied to all branches of philosophy; one tried to derive even the elementary principles of human morality from "rational" considerations that were as compelling as geometric proofs (Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata, 1677).

In the theory type of empiricism, only those hypotheses are recognized that can be traced back to "sensual perception". Among others, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and David Hume were committed to it. The principle of deriving all knowledge from sensory experience has, as the basis of scientific work, an overriding importance up to the present day. Analytic philosophy is also rooted in this tradition of thought.

The emancipatory bourgeois movement of the Enlightenment elevated reason to the basis of all knowledge and the standard of all human action. It demanded human rights and thought about the restoration of an "unadulterated natural way of life". It advocated the separation of state powers (Montesquieu) and the right of the middle classes in particular to have a say. A theoretical basis for this was the idea of a social contract (e.g. in Jean-Jacques Rousseau); constitutions were to secure the new rights. The French Enlightenment thinkers Voltaire and Diderot criticized the power of the church and absolutist monarchs. The encyclopaedists (d'Alembert) attempted for the first time to summarise all the knowledge of their time in an encyclopaedia. More radical representatives of the French Enlightenment were Holbach, who for the first time sketched a naturalistic view of man in the sense of natural science without God and metaphysics, La Mettrie, who saw man as a machine and pleasure as the goal of life, and Sade, who drew the conclusion from both to deny any generally binding ethics.

Finally, one of the central philosophers of the modern era, Immanuel Kant, elaborated his critique of knowledge, which many contemporaries regarded as revolutionary. It states that we cannot know the things themselves, but always only their appearances, which are preformed by the possibilities offered by the mind and the senses. According to this, all cognition is always dependent on the cognizing subject. Kant's further works on ethics ("categorical imperative"), aesthetics and international law (Zum ewigen Frieden, 1795/96), among others, also had considerable significance for the following centuries.

19th century

→ Main article: Philosophy of the 19th century

Part of philosophy in the first half of the 19th century was characterized by the striving to "complete", "improve" or surpass Kant's insights. Characteristic of German Idealism (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel) are the all-encompassing speculative metaphysical systems, in which the "I", the "Absolute" or the "Spirit" determine the foundations of the world.

Another direction was taken by empiricist currents such as positivism, which wanted to explain the world with the help of empirical sciences alone, i.e. without metaphysics. In England, Bentham and Mill developed utilitarianism, which gave important impulses to economics and ethics through a consistent cost-benefit concept and with the idea of a kind of "prosperity for all" (the principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number). Along with the philosophy of history, economics is also central to the philosophy of Marx, who, following Hegel and the materialists, founded communism. Marx demanded that theoretical reflections be measured against the transformation of concrete social conditions:

"Philosophers have only interpreted the world differently; but what matters is to change it."

- Karl Marx: Theses on Feuerbach, MEW vol. 3, p. 535 (1845)

Prominent thinkers who broke new ground were Arthur Schopenhauer, Sören Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. Schopenhauer, following Indian philosophy, emphasized the priority and supremacy of the will over reason. His pessimistic worldview, informed by the experience of suffering, also draws from Buddhist ideas. Friedrich Nietzsche, who like Schopenhauer had a great influence on the arts, described himself as an immoralist. For him, the values of traditional Christian morality were an expression of weakness and decadence. He addressed ideas of nihilism, the superman, and the "eternal return," the endless repetition of history. The religious thinker Sören Kierkegaard was in some ways a precursor of existentialism. He represented a radical individualism, which does not ask how one can act right in principle, but how one has to behave as an individual in the respective concrete situation.

20th century

→ Main article: Philosophy of the 20th century

The philosophy of the 20th century was characterized by a wide spectrum of positions and currents. In its beginnings, this century was characterized by a strong belief in progress and science. It was not until the second half of the 20th century - which on the social level had brought the experience of the two world wars, the Shoa and the threat to the planet from nuclear weapons, and which had brought to the fore the threat to ecosystems posed by human beings themselves - that the sceptics of progress, who had largely been marginalised after Rousseau, came to the fore again in philosophy as well.

The enormous successes of technology in the 19th century led to a strengthening of neopositivist positions. The logical empiricist Rudolf Carnap pleaded for the complete replacement of philosophy by a "logic of science" - i.e. by the logical analysis of the language of science.

The critical rationalist Karl Popper argued that scientific progress occurs primarily through the refutation of individual theories through experiments ("falsification"). In his view, those scientific theories that come closest to the truth prevail in an evolutionary selection process. Thomas S. Kuhn, on the other hand, considered different theories on the same question to be incomparable in principle, and a superiority of one over the other therefore not objectively justifiable, which would make the dominance of one theory a matter of rhetoric. Paul Feyerabend's plea for methodological freedom went in a similar direction. Finally, for pragmatism, theories must be judged from the point of view of their usefulness and applicability in practice.

As a reaction to the increasing scientification of all areas of life, those currents of thought can be understood that turn to the individual and to life. The basic understanding of the philosophy of life was that the wholeness of life cannot be described by science, concepts and logic alone. Henri Bergson, for example, saw a fundamental difference between individually experienced time and the analytical time of natural science. Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, was similarly critical in calling for the analytical consideration of things to be based first on what appears immediately to consciousness, in order to avoid a rash interpretation of the world. The existential philosophy of his student Martin Heidegger was of great influence. His starting point was the analysis of the general human condition and led him to the question of the meaning of being in general.

Following Heidegger, existentialism, represented in particular by Jean-Paul Sartre, advocated the thesis that man is "condemned to freedom". With each of his actions, he had to make a choice for which he was responsible.

"There is only one really serious philosophical problem: suicide. To decide whether life is worth living or not is to answer the basic question of philosophy. Everything else - whether the world has three dimensions and the mind nine or twelve categories - comes later. These are gimmicks; first you have to answer."

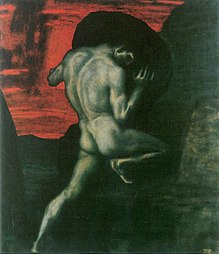

- Albert Camus: The Myth of Sisyphus, chap. "The Absurd and Suicide" (1942)

The 20th century was marked by social upheaval and the conflict between Soviet communism and Western capitalist forms of society. In the course of this conflict, which culminated in the Cold War and assumed worldwide dimensions with globalization, questions of history and social philosophy were strongly accentuated in the philosophical debate.

In Prinzip Hoffnung, Ernst Bloch sought to prove the "kingdom of freedom" envisioned by Karl Marx at the end of all class struggles to be a concrete utopia that had the advantage over all previous utopias of being based on the foundation of dialectical materialism. Herbert Marcuse and the founders of Critical Theory, Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, also developed their philosophical approaches to the problem of alienation against the background of the social analyses of Marx and Engels. With Jürgen Habermas, the Critical Theory, also known as the Frankfurt School, has produced a philosopher who, with his theory of communicative action and the ideal of "discourse free of domination", is also committed to the model of a society freed from dependency relationships, but at the same time appreciates the potential of Western democracies, which is rich in opportunities. The pioneer of communitarianism, Charles Taylor, warns of the dangers of an "atomistic individualism" in modern societies. He sees the way to the preservation or creation of humane social and ecological living conditions in a balance between individual rights and the community obligations of people that has yet to be found.

Present

→ Main article: Contemporary philosophy

Contemporary philosophy faces the problem of grasping its subject matter at all, since a retrospective evaluation of the various approaches cannot yet be made. However, the philosophy of science has been further developed by coining clearer concepts of "confirmation" and "theory reduction".

Since the end of the 19th century, language has been accorded an increasingly central position in philosophy. Ludwig Wittgenstein developed a completely new understanding of language, which he conceived as an unmanageable conglomerate of individual "language games". Philosophy, he argued, only deals with "pseudo-problems", i.e. it merely cures its own "confusions of language". Philosophizing was therefore not an "explanatory" but a "therapeutic" activity:

"Philosophy is a struggle against the bewitchment of our minds by the means of our language."

- Ludwig Wittgenstein: Philosophical Investigations, p. 109 (1953)

Analytic philosophy, initially oriented mainly towards the philosophy of language, dominates the method of academic philosophy in Anglo-Saxon contexts and increasingly also in the German-speaking world. At most universities, however, there is a pronounced pluralism with regard to the philosophical topics and currents taught.

In the German-speaking countries it has received little attention, but neo-scholasticism, especially neo-Thomism, has been an influential current in contemporary philosophy ever since the Catholic Church made it the official doctrine of priestly education at the end of the 19th century.

Postmodernism (e.g. Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Derrida) is a counter-movement to the ideas of modernity and emphasizes the differences of worlds of thought and life. It also assesses human identity as unstable. Feminist philosophy, which is close to postmodernism, aims at the dependence of the interpretation of the world on gender.

Franz von Stuck, Sisyphus (1920). The myth of Sisyphus has been used by Albert Camus to symbolize the meaninglessness of life as perceived by modern man. Sisyphus accepts the absurdity of his existence in a chaotic world ruled by chance.

Adolph von Menzel: "The Iron Rolling Mill" (1872/75). The picture often serves as an illustration of the social catastrophe that industrialization meant for wage workers. This led to the development of philosophical theories that were to determine world history for 150 years.

Detail from Raphael's "The School of Athens" (1510-1511), fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura (Vatican). Among others, Zeno of Kition, Epicurus, Averroes, Pythagoras, Alcibiades, Xenophon, Socrates, Heraclitus, Plato, Aristotle, Diogenes, Euclid, Zarathustra and Ptolemy are depicted. The central perspective layout of the mural in the Vatican aims at the imagined representations of Plato and Aristotle at the center of the composition. Opposite the fresco is the parallel work of Raphael's Disputa del Sacramento, the Disputation on the Sacrament.

Albrecht Dürer: Self-Portrait (1500). The painting has often been interpreted as marking, with its depiction of an individual in the pose of Christ and thus of a god, the fundamental change in the direction of vision from God to the individual human being at the turn of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Benozzo Gozzoli, "Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas over Averroes" (1468/84), detail. Thomas is enthroned between Aristotle and Plato, whose teachings he tried to combine, before him lies prostrate the Spanish-Arab philosopher Averroes. (Fantasy Portraits)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the definition of philosophy?

A: Philosophy is the study of underlying things. It tries to understand the reasons or basis for things and how they should be.

Q: What does "Philosophia" mean?

A: "Philosophia" is the Ancient Greek word for the "love of wisdom".

Q: Who works in the field of philosophy?

A: A person who works in the field of philosophy is called a philosopher.

Q: What does a philosopher do?

A: A philosopher is a kind of thinker and researcher.

Q: Can philosophy also refer to a group of ideas or way of living suggested by philosophers?

A: Yes, it can. Philosophy can also mean a group of ideas or way of living suggested by philosophers.

Q: How can we think about philosophy?

A: We can think about philosophy as a way of thinking about the world, universe, and society.

Q: Was natural science part of philosophy in past times?

A:Yes, natural sciences were once considered part of philosophy in past times.

Search within the encyclopedia