Persepolis

![]()

This article is about the capital of the ancient Persian Empire; for further explanation, see Persepolis (disambiguation).

29.934444444452.8913888889Coordinates: 29° 56′ 4″ N, 52° 53′ 29″ E

The ancient Persian residential city of Persepolis (New Persian تخت جمشيد Tacht-e Dschamschid, DMG Taḫt-e Ǧamšīd, 'Throne of Dschamschid', Old Persian: Parsa) was one of the capitals of the ancient Persian Empire under the Achaemenids and was founded in 520 BC by Darius I in southern Iran in the region of Persis. The name "Persepolis" comes from the Greek for "city of the Persians"; the Persian name refers to Jamshid, a Persian king of mythological antiquity, from whose flying throne crashed remains are said to have formed the site. Another name from the Middle Ages was Čehel-menār (Persian چهل منار) meaning Forty Minarets.

When the former residence Pasargadae was moved here by 50 km, a terrace of 15 ha was built at the foot of the mountain Kuh-e Mehr, or Kuh-e Rahmat (with the same meaning from Arabic). Over 14 buildings were erected on the platform under Darius I and his successors, including Xerxes, Artaxerxes I, and Artaxerxes II. Other palaces were excavated immediately at the foot of the terrace. The palace city was destroyed by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, but its (partly rebuilt) remains can still be visited today. Since the irrigation systems were also destroyed in the destruction, the buildings were largely covered by desert sand and thus preserved. They are part of the UNESCO world heritage and can be visited about 60 km northeast of the city of Shiraz on the plateau of Marvdasht in the province of Fars (900 km south of Tehran).

Detail of a relief of the Apadana stairways

.webm.jpg)

Play media file Animation of the city of Persepolis

Discovery Story

The first European travellers visited the ruins of the palace complexes as early as the Middle Ages (for example, Giosafat Barbaro). Numerous reliefs were brought to European museums in the course of the explorations. The first systematic excavations were carried out from 1931 to 1939 on behalf of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago by archaeologists from Germany, especially Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter and Erich F. Schmidt. Since 1939 Persepolis has been explored by Iranian archaeologists. A significant part of the excavation documentation and find circumstances, copies of inscriptions and an extensive photo archive of the excavations of Persepolis can be found today in the Ernst Herzfeld estate in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Description of the complex

Front steps

Near the northwest corner of the terrace is the entrance staircase. On its underside is a courtyard of cut stones, 10 cm higher than its surroundings. From there, a symmetrical double staircase leads up. After 63 steps, the stairs reach a landing, from where the path leads 48 more steps in the opposite direction. The stairs thus cover almost 12 metres, with steps 6.9 metres wide, 38 metres deep and 10 cm high each. At times, load-bearing animals have been led into the complex via these stairs, but it was probably not permitted to ride horses over the stairs. The staircases were cut from large and irregular limestones, which were joined together with staples, but without mortar. This construction method and the cut of the stones indicate that the stairs were built during the time of Xerxes. In the 1970s, an Iranian-Italian team restored the staircase after it had been damaged by wear and weathering.

Goal of all countries

The Gate of All Lands was a small square palace with a side length of 24.75 meters. It was mostly built and completed during the reign of Xerxes I. It is located about 22 meters from the edge of the terrace and had a height of 18 meters.

The ceiling of the Gate of All Lands was supported on four columns a good 16.5 meters high. The base of these columns was bell-shaped and had vertical fluting. On this base was a torus, a wheel-shaped stone. On top of it sat the cylindrical high shaft with 48 grooves (fluting). On this shaft was the wreath of columns in the form of flowers, and on this wreath in turn sat the capital in the form of a double-headed bull. The main beams of the palace were between the neck and the two heads of the bulls. Two of these columns still stand upright today. Another column was re-erected in the 1960s from pieces lying around and found during the demolition of an adobe wall built later.

The gate of all countries was equipped with three porticoes. The east and west gates were 10 meters high and had a width of 3.82 meters. The west portico had on each side a very large guardian bull similar to the Assyrian tradition, but with four legs instead of five and depicted in motion. Above this protector bull are two inscriptions in three languages, namely Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. In them Xerxes praises the god Ahuramazda, proclaims his lineage, the building of the palace complexes by him and his father, and asks for protection for his city. The east portico has sphinxes on each side with human heads, bull bodies, crescent eagle wings, cylindrical crowns and three pairs of horns. They look towards the east. The south portico is larger than the east and west porticoes, but has no decorations.

The inside of the Gate of All Lands was a large hall with four columns, in which there was a black stone bench for waiting royal visitors. The interior walls were decorated with colored tiles showing rosettes, palm trees and other decorations. Some of these have been preserved and are now in storage at Persepolis. The gates were made of wood, which was probably covered with precious metal plates. Smaller doors were built into the lower part of the wooden gates. The purpose of this building was to be a waiting room for the representatives of all the nations under the rule of Persia, and all their representatives had to pass through the Gate of All Lands before going to the Audience Palace. The entrance to the Gate of All Countries was through the West Gate, which was 22 meters away from the entrance stairs. Iranian dignitaries probably used the east portico to go towards the Hundred Pillars Palace. All other dignitaries exited the Gate of All Countries through the South Portico towards Apadana.

Astronomy

The location and orientation to the Kuh-e-Rahmat seems to have been carefully chosen: On the equinox (21 March), the date of the Persian New Year, the morning sunlight falls through the "gate of all lands" (but an aisle was necessary because of the mountain). Archaeoastronomy suspects other calendrical functions of the site. It presents itself according to several cardinal points - but is west dominated, although actually directions after sunrise would be expected. The "Gate of All Lands" was built by Xerxes I after his accession to the throne, who moved the main access to the palace complex from the south to the west and had a double flight of stairs built for this purpose.

Apadana

The largest palace in Persepolis is the Apadana Palace, built by Darius I around 515 BC and extended by his successors. Xerxes I in particular had numerous changes made to the Apadana. Due to the new main entrance of Persepolis from the "Gate of All Lands", he also moved the main entrance of the palace from the east to the north. For this purpose a new portico was built. Xerxes I then had the so-called "Treasure House Relief", on which he as prince and his father Darius were depicted, removed and brought into the Treasure House. The relief was replaced by 8 Persian soldiers. The Apadana Palace also contained the throne of the king. The gift-bearing delegations of the countries that were part of the Persian Empire are particularly finely carved on the east portico of the Apadana Palace. The representatives of the nations can be seen bringing gifts to the Persian king. It is conspicuous that there is no fighting at all in Persepolis. The delegations of gift-bearers are also led to the king by Persian and Median court officials, alternately "holding hands".

The "Darius Palace" is the best preserved palace in Persepolis. Here the huge door and window frames are still clearly visible. The reason for the good condition of this palace is most likely that the basic structure was built mainly of massive stone blocks. They weigh several tons, and the reliefs on the inside of the door frames are still relatively well preserved.

Via the "Road of the Army" you can get to the palace of Xerxes I, the "Hundred Pillars Hall", located in the east of Persepolis. The palace got its name from the fact that the roof of the hall was supported by one hundred columns. Today, however, none of them is still standing. In the Hundred Pillars Hall most traces of fire were found, burnt materials are exhibited in the museum. This is not surprising in that Alexander the Great had Persepolis set on fire.

While the nearly 15-hectare platform contains only one royal tomb, the others are housed a few kilometres away in a steep rock face, the Naqsh-e Rostam. Only a steep climb leads to the burial chambers of Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The interior was looted early and contains no reliefs (anymore). On the outside, however, parts of the bodyguard from the "10,000 Immortals" can be seen, the elite unit of the Persian Empire, which consisted exclusively of Persians.

Reliefs of the Apadana

The northern, as well as the eastern side stairway to the Apadana are decorated with various wonderful reliefs, whose high-quality stones have largely survived the devastating fire. The representations on both stairways are very similar and differ only in a few points, starting from the north-east corner the motives are point-symmetrically attached to the facades. Whether the differences between the two stairways are of chronological origin or caused by the simultaneous work of different groups of craftsmen remains controversial.

In the following, the representations will be described, starting from the north-east corner of the apadana as the central point of departure. The reliefs on the nearest stairways show soldiers arranged in three registers, high dignitaries, as well as charioteers and horses led by reins. The central stairways in front of each one originally had a relief depicting an audience scene. These were probably replaced by antithetically arranged soldiers during the reign of Artaxerxes I (see photo on the right), the old relief panels were moved to the Treasury House. The outer stairways show in long rows the representations of the 28 nations like Medes, inhabitants of Babylonia, Arabia and Egypt, furthermore Greeks, Scythians and Indians - recognizable by their costumes as well as typical gestures and weapons with which they bring the gifts of their countries to the king for the New Year celebration. There are, for example, long pleated robes from Assyria, some Indians with finely woven cloaks or Syrians with surcoats and stoles.

Hundred Pillars Palace

The Hundred Pillars Palace was the second largest palace in Persepolis. Its central hall ("Hundred Pillars Hall") had dimensions of 68.5 meters wide and 68.5 meters long, making it the largest hall in the ancient world; the central hall of the Apadana was also smaller. The ceiling of the Hundred Pillar Palace was supported by 100 pillars arranged in 10 rows of 10 pillars each. A stone tablet found by Ernst Herzfeld in the southeast corner of the palace records that construction of the palace began in 470 BC under Xerxes I and was completed around 450 BC under Artaxerxes I. The fire which Alexander the Great ordered to be set after the conquest of Persia was so severe that only the bases of the columns and the doorways remain of the palace; they were uncovered under a layer of cedar ash and earth three feet thick.

The columns of the palace consist of a bell-shaped base, a round torus and a fluted shaft on which multiform leaf wreaths sit. At the very top are capitals with double-headed bull protomes. Two surviving capitals have been in Chicago since the 1930s.

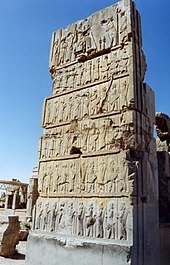

The portals of the two north gates show four times the same audience scene with the king sitting on the throne, a Mede reporting to the king, a courtier with a fly-wing, an armour-bearer and Persian guards. The canopy under which the scene takes place bears the winged ox as a symbol of Iranian rule, flanked by bulls and roaring lions. Below the scene are five rows of soldiers. The west and east gates are much smaller than the north gate. Their portals show the king fighting a winged lion and a bull and a roaring lion, respectively. These reliefs resemble those in the Darius Palace and the Xerxes Harem. The porals of the southern gates bear reliefs depicting King Artaxerxes I being carried into the palace on his throne. The top panel of the reliefs shows the king seated on his throne. Behind him stands a eunuch with a fly-whisk and a sweat-cloth in his hands. Below this relief are fourteen throne-bearers each, resulting in 28 throne-bearers per gate. The throne-bearers are identical to the throne-bearers of the central palace with regard to their arrangement and costumes.

The direction of the king's gaze on the reliefs suggests that the south gates formed the entrance and the north gates the exit. Unlike the Apadana, the Hundred Pillars Palace may have been reserved for the army commanders of the empire.

Other archaeological remains

One good thing came out of the fire: The fire hardened about 30,000 clay tablets and preserved them perfectly for more than 2,500 years. Thus, today's archaeologists can read many details, up to the accounting of the city administration.

Parts of the palace area were apparently already planned before Darius I. The third Achaemenid king, who reigned for 36 years, also had a richly furnished winter palace built in the much milder climate of Susa and a trunk road with 22 post stations at intervals of 24 km constructed. Susa lies 400 km to the west, at the present-day city of Abadan near the Iraqi border. Here, too, most of it has been destroyed, as has the first ancient Persian residence, Pasargadae, near Persepolis.

In addition, the clay tablets proved that Persepolis was not built by slaves. Many of the clay tablets contain notes about food rations and remuneration of the workers, who had been ordered from all over the country especially for this giant project to Persepolis. The basic wage consisted of about 30 liters of barley per month, which made it possible to bake about 1 pound of bread per day. Additional rations were distributed on special occasions or for work well done, in the form of smaller quantities of meat or wine.

Surroundings

Barely 4 km north of Persepolis is Naqsh-e Rostam with a gallery of four rock tombs dating back to the kings Darius I (522-485 BC), Xerxes I (485-465 BC), Artaxerxes I (464-425 BC) and Darius II (425-405 BC). Similar to the two large tombs at Persepolis, these tombs were also carved into vertically sloping wall alignments.

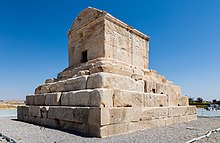

The tomb of Cyrus II the Great in Pasargadae

Column

Relief on the portal of a southern gate of the Hundred Pillars Palace

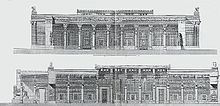

Reconstruction of the palace by Charles Chipiez (1884)

View from the north over the Hundred Columns Palace

Bas-relief on the front staircase of the palace

Apadana hall, above: the sign of Faravahar guarded by Lamassus

Northern stairway to the Apadana (relief detail)

Palace Darius I

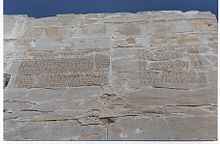

Inscriptions of Xerxes

Persepolis, the palace of Darius, 2005

Front steps

Goal of all countries

Search within the encyclopedia