Peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg (often abbreviated to Augsburg Religious Peace) is an imperial law of the Holy Roman Empire that permanently granted the adherents of the Confessio Augustana (a confessional text of the Lutheran imperial estates) their vested rights and free exercise of religion. The law was concluded on 25 September 1555 at the Diet of Augsburg between Ferdinand I, who represented his brother Emperor Charles V, and the imperial estates.

The Augsburg Imperial Treaty is composed of two major parts: Those regulations which exclusively determined the relationship between the confessions (Augsburg Religious Peace, §§ 7-30), and those which established more general political decisions (Imperial Execution Regulations, §§ 31-103).

With the Peace of Augsburg, the fundamental conditions for a peaceful and lasting coexistence of Lutheranism and Catholicism in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation were established for the first time through imperial legal resolutions. These included, on the one hand, a far-reaching realization of the parity of the confessions through the principle of equality, and, on the other hand, the implicit proclamation of a land peace, for "in lasting division of religion, a supplementary tractation and act of peace in both, religious, prophan and secular matters, will not be accepted" (§ 13 of the Imperial Decree). Moreover, the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace displaced the idea of a universal Christian emperorship, although it did not exclude the idea of an eventual reunion of the two confessions at a later date. In general, the Augsburg Religious Peace is seen as the provisional conclusion of the Reformation era in Germany, which had been initiated by Martin Luther in 1517.

After lengthy negotiations, agreement was reached on the ius reformandi: by means of the (subsequently introduced) formula Cuius regio, eius religio, the Augsburg Religious Peace empowered the respective sovereign to determine the religion of his subjects; the latter, on the other hand, were granted the right to leave their country by means of the ius emigrandi. In addition to these simple and easily understandable basic regulations, however, the treaty also contained complicated special and exceptional regulations, which were often contradictory and thus made the religious peace a confusing and complicated treaty. This resulted in numerous theological controversies in the following period, which reached their climax especially in the course of the increasing aggravation of the conflict situation from the 1570s onwards.

With regard to the long-term consequences of the Augsburg Religious Peace, it can therefore be stated that, on the one hand, it created legal clarity in some confessional and political matters, thus heralding one of the longest periods of peace in the empire (from 1555 to 1618); on the other hand, however, some problems persisted subliminally, while others were even created anew by ambiguities, contradictions and complications. Together, these contributed to an increase in the potential for confessional conflict, which, together with the latent political causes, was to lead to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618.

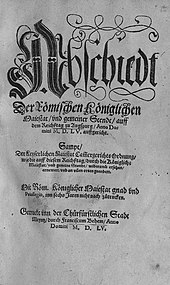

First page of the document printed by Franz Behem in Mainz

Augsburg: The two towers of the Protestant (in the foreground) and the Catholic Ulrich Church stand for religious peace in the city.

Previous story

At the beginning of the 1930s, the Reformation spread to many territories and imperial cities of the Holy Roman Empire. This raised the question of the legal status of Protestantism, whose teachings were officially considered heresy. In the eyes of many Catholics, the Roman-German Emperor had to counter the spread of such "heresies". As a result of the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1530, nothing changed in the imperial legal position of Protestantism, especially since the Confessio Augustana, a fundamental confessional document of Lutheranism, was not accepted by the emperor and the Catholic estates (see also Confutatio Augustana). In order to prevent a possible military recatholicization of Protestant territories, the Protestant imperial estates then founded the Schmalkaldic League on February 27, 1531. In the following years, several religious discussions took place in order to restore the unity of the church. When these failed - also due to political motives - Emperor Charles V decided to take military action against the League and defeated it in the Schmalkaldic War in 1547.

At the "harnessed" Augsburg Diet of 1548 (so called because Charles's troops were still in the empire), the emperor attempted to use his military victory at Mühlberg politically as well: He forced the Protestant imperial estates to accept the Augsburg Interim. The Interim was intended to regulate ecclesiastical conditions until a general council would finally decide on the reintegration of Protestants into the Catholic Church. However, the largely pro-Catholic provisions issued by Charles were not enforced, or were only half-heartedly enforced, except within the direct reach of imperial power in the south of the empire and in the imperial cities.

At the same time, the question arose as to who should succeed Charles V in the empire. This problem also contributed to the intensification of the existing conflict between the Estates and the Emperor: The emperor himself tried to push through his plan of the so-called Spanish succession, that is, the transfer of the Roman-German imperial dignity to his son Philip II of Spain during his lifetime, in the empire. His brother Ferdinand I, on the other hand, who had already been elected Roman king in 1531, wanted to claim the imperial crown for himself and his descendants. The majority of the imperial estates were more inclined to Ferdinand's position in this matter. They feared that a successor from the Spanish line would be a first step towards a hereditary, Habsburg universal monarchy. In addition, this would at the same time considerably limit their Teutonic liberties, their estates' freedoms.

Moritz of Saxony, despite his Protestant faith, had supported the Emperor in the Schmalkaldic War and received the Saxon electorship for this in 1547. Afterwards, Moritz found himself in a difficult position: he was isolated within the Protestant camp, but was aware that the Emperor's strong position could not last. Therefore, he placed himself at the head of a rebellion of princes rebelling against the Spanish Succession. Because of this change of sides, Moritz was called Judas of Meissen by Catholics and the savior of the Reformation by Protestants. The ensuing war between princes caught Charles completely off guard in 1552 and forced him to flee. The Emperor was not present at the negotiations held in Passau to settle the conflict. Ferdinand I acted as mediator and negotiated with the princes.

In general, the longing for peace gradually arose in the Empire after the numerous unrest and confessional wars of the Reformation period. The War of the Princes was immediately followed by the Second Margravial War (1552-1555), triggered by the territorial claims of Albrecht Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. The military and political stalemate between Lutherans and Catholics reduced the hope of being able to further expand one's own sphere of influence. This favored peace inclinations - both sides were willing to make concessions for a comprehensive peace settlement.

Ferdinand I, brother of the reigning Emperor Charles V, had probably come to the realization through the Schmalkaldic War and the subsequent rebellion of the princes that Protestantism could not be defeated by military means. He then convened a Diet in Passau in 1552 to negotiate the relationship between the two confessions with princes and estates of a generation that was now comparatively willing to compromise. The resulting Treaty of Passau, whose provisions were limited in time, was, however, merely a "transitional solution" to religious policy, a "truce". The reason for this was Charles' refusal to sign a treaty that made permanent concessions to the Protestants. Nevertheless, the Treaty of Passau was a step towards a lasting peace, which was to be concluded three years later in Augsburg.

After the Treaty of Passau, Charles V realized that his lofty political goals in the Empire had largely failed and slowly initiated his resignation. He moved to Brussels in 1553 and did not return to the Empire for the rest of his life. He placed imperial politics almost entirely in Ferdinand's hands.

Emperor Charles V after the Battle of Mühlberg, painting by Titian from 1548

The Imperial Diet of 1555

After the imperial estates had assembled in Augsburg, the Diet was opened on 5 February under the leadership of Ferdinand I.

Because of his promise to settle the religious question in the empire at the next imperial diet, Charles found himself on the defensive and tried to postpone it as long as possible. Only after long pressure from the imperial estates did Emperor Charles V give in in 1553. At this Diet, too, the Emperor would have preferred to decree only a provisional settlement, but the Estates of the Empire pressed for a permanent solution. Under no circumstances did the Emperor wish to attend the Diet in person. It is clear from the Emperor's letters that he did so partly out of consideration for his personal salvation, but also for health reasons.

In the Imperial Diet Proclamation, Charles and Ferdinand deliberately avoided any mention of the Treaty of Passau. From their point of view, the focus of the Diet was on comprehensively securing the land peace. This complex of issues had been well prepared by previous consultations and could be concluded relatively quickly. The rather difficult question of religion, on the other hand, was not to be discussed until this complex of topics had been concluded, since the Emperor and his brother feared that the Imperial Estates would not be able to reach agreement and that the entire Diet would end without a result. The imperial estates rejected such a sequence of negotiations and placed the religious peace as the first item on the agenda.

The concept of a political peace, which deliberately excluded religious differences and on which the Augsburg Peace Treaty was ultimately based, originated from a proposal made by Moritz of Saxony during the Passau negotiations. This basic idea was considered promising and an ideal starting point for the solution of the religious question in the empire, since an early agreement on theological-dogmatic questions was very unrealistic. The widespread conviction in the Empire that a reunification of the confessions was a prerequisite for a comprehensive peace settlement was gradually replaced by the insight that a political solution was more important than the elimination of theological differences.

One of the main difficulties during the negotiations was that the legal recognition of the confessional division of the empire was not compatible with canon law. Cumbersome legal formulations were intended to disguise this fact and to make it easier for the Catholic (and especially the ecclesiastical) imperial estates to accept the peace.

The question of whether every person could freely choose their confession or whether this freedom of choice should only apply to the authorities was hotly disputed and was one of the central questions of content. The Protestants in particular demanded the exemption at least for certain groups of persons (the imperial knights, imperial and provincial cities). The agreement finally reached, with freedom of worship in the imperial cities and the ius emigrandi, was an important foundation of the entire religious peace. Medieval legal statutes against heresy were thus effectively abolished.

The toughest and longest negotiations, however, took place around the spiritual reservation. Irreconcilable theological, legal and political differences threatened to cause the negotiations to fail several times. The Protestants could not accept the spiritual reservation, as they saw it as a one-sided advantage for the Catholic side. Ferdinand tried to obtain their consent by means of a secret side agreement - the Declaratio Ferdinandea. In the end, the spiritual reservation was only included in the treaty by virtue of Ferdinand's royal authority - the Protestant estates had not agreed to it. From this they later derived the consequence that they were not bound by it. The Declaratio Ferdinandea, however, was not part of the treaty. The question of its validity remained open.

Shortly before the end of the negotiations, the Emperor made it clear to Ferdinand that he was under no circumstances prepared to share political responsibility for the compromise reached in Augsburg. Charles saw the loss of importance of the office of emperor that a religious division of the empire would bring. He therefore asked his brother to delay the Imperial Diet and to await his personal appearance at the Diet. Ferdinand was glad that a workable consensus had been reached after difficult negotiations, and did not comply with this request. In order not to jeopardize the Reichstag farewell, Ferdinand also concealed his brother's threat of resignation from the imperial estates.

The Religious Peace was part of the Imperial Diet's agreement of September 25, 1555. In addition to the Religious Peace itself, the agreement also contained amendments to the Chamber Court Rules and the Execution Rules to enforce the Land Peace. Lutherans were now also admitted to the Kammergericht as assessors and judges.

.jpg)

Allegory of the Peace of Augsburg 1555, part of the Luther Monument in Worms

Search within the encyclopedia