Pax Romana

![]()

This article describes the peacetime in the Roman Empire. For the Christian organization, see Pax Romana (union).

The Pax Romana ("Roman Peace") or Pax Augusta (Latin for "Peace of Augustus") is the term used to describe a period of the Roman Empire lasting about 200-250 years, which, despite individual revolts and brief civil wars, was characterized overall by internal peace and stability. The emperors (Augusti) acted as guarantors of internal peace. This phase began in 27 BC with the end of the Roman civil wars and the res publica libera under the first Roman emperor Augustus, who established a de facto autocracy (principate), and ended either in 192 AD with the death of the emperor Commodus or in 235 AD with the end of the Severan dynasty (see also Optimum of the Roman period).

The catchword Pax Romana or, more often, Pax Augusta, always meant above all internal peace, i.e. the absence of civil war. Compared to the previous century, when the Roman Republic had perished in long civil wars while in the East the former order of the Hellenistic world was breaking up, and in contrast to the rule of many later emperors, the early Principate actually brought Rome, Italy and most of the provinces a long-lasting period of internal peace, stability, security and prosperity. After the devastation of the civil wars, the economy flourished, as did art and culture. The period produced poets like Virgil, Horace, Ovid and Properz, historians like Titus Livius or architects like Vitruvius.

Rome changed, as Augustus thought, from a city of bricks into a city of marble. Impressive architectural testimonies of this period have survived to this day, such as the Marcellus Theatre, the Pantheon built by Agrippa and renewed under Emperor Hadrian, and last but not least Augustus' mausoleum and the Ara Pacis, the Altar of Peace from 9 BC, which shows a procession of the imperial family in relief and is meant to celebrate the prosperity of the pacified empire.

Contrasting with the internal peace, however, was the series of wars waged on the frontiers, beginning at the latest in 16 BC. The empire expanded under Augustus to an extent never before or since. Besides rich Egypt and Galatia, provinces were added to it on the Rhine and Danube, the conquest of which was comparable only to that of Gaul by Julius Caesar. War against external enemies was not regarded as contradictory to the Pax Augusta. Therefore, Augustus, under whom the empire waged very extensive wars of conquest, was nevertheless able to be celebrated as an emperor of peace.

For there was little sign of war within the empire and the provinces after the year 31 BC. Peace and prosperity were therefore already perceived by contemporaries as a defining characteristic of the epoch. This was the reason why they resigned themselves to the introduction of the monarchy and the end of the republic: The loss of freedom was the price to be paid for the pacification of the empire. Conversely, this meant that the legitimacy of imperial rule depended to a large extent on the Augusti actually fulfilling the promise to ensure peace and security in the empire.

The state stabilized: although the empire continued to face external enemies on its borders, such as the Germanic tribes on the Rhine and Danube and the Parthians in the east, and emperors such as Trajan waged offensive wars of conquest, cultural and economic life flourished in the pacified interior, with the population largely sealed off from external dangers. Many cities no longer had walls. It was not until after the death of Marcus Aurelius and then increasingly during the imperial crisis of the 3rd century that groups of marauding enemies repeatedly broke into the empire, while at the same time the internal stability diminished and civil war broke out again and again. In late antiquity, stabilization was only partially achieved before the Western Empire collapsed in the 5th century after endless internal and external wars.

On coins, the Pax Augusta was propagated as the foundation of imperial legitimacy even into the late Roman period. On the reverse of coins the goddess Pax is often shown with the abbreviated transcription PAX AVG. Where the abbreviation PAX AUGG is found, it is intended to indicate peace secured by two emperors ruling at the same time. The abbreviation PAX AVGG ET CAESS refers to the two senior emperors and their Caesars as junior emperors at the time of the tetrarchy. Rarely, the abbreviation AVGGG is also found for the four tetrarchs.

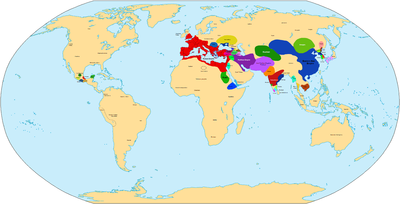

The global situation around the year 200 AD.

The global situation during the Pax Romana around the year 50 AD.

Scope of the Pax Romana - The Roman Empire at the time of its greatest expansion under Emperor Trajan 117

PAX AVGG with Pax, on Antoninian of Emperor Maximianus, Kampmann 120.41

See also

- Roman-Indian relations

- Economy in the Roman Empire

- Roman-Chinese relations

Search within the encyclopedia