Paul the Apostle

![]()

Paulus is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Paul (disambiguation).

Paul of Tarsus (Greek Παῦλος Paûlos, Hebrew name שָׁאוּל Sha'ul (Saul), Latin Paul; * probably before the year 10 in Tarsus/Cilicia; † after 60, probably in Rome) was according to the New Testament (NT) a successful missionary of early Christianity and one of the first Christian theologians. His historicity is considered certain by most researchers.

As a Greek educated Jew and law-abiding Pharisee with Roman citizenship Paul first persecuted the followers of Jesus Christ, whom he never met except for His appearance at his conversion. Since his conversion, however, he saw himself as a divinely appointed apostle of the gospel to the nations (Gal 1:15 f. EU). As such he proclaimed the risen Jesus Christ especially to Gentiles. For this purpose he traveled through the eastern Mediterranean and founded some Christian churches there. Through his letters he remained in contact with them. These oldest preserved early Christian writings, the so-called Pauline Epistles, form an essential part of the later NT.

The essential characteristic of Paul's theology is the concentration of the Christian faith on the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ with constant reference to the promises of the Tanakh. Through the substitutionary fulfillment of the Torah by Jesus Christ, the Son of God, Paul found man's justification and his reconciliation with God established by grace. These themes, in various interpretations, became basic building blocks for the teachings of many Christian denominations.

Orthodox churches, the Roman Catholic Church, the Coptic Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Anglican Communion venerate Paul as a saint. Protestant churches commemorate him with memorial days. His letters have influenced church fathers and leading Christian theologians, and thus greatly influenced European intellectual history. Since the Enlightenment, many historians see Paul as the actual founder of Christianity as an independent religion.

Apostles Paul (right with book, sword and half bald head) and Mark. One of the two panels of the diptych The Four Apostles by Albrecht Dürer 1526.

Apostle Paul by Bartolomeo Montagna 1482.

Apostle Paul, painting by Anthonis van Dyck c. 1618-1620.

Live

Year of birth

An estimate of the year of birth can be based on two statements made by Paul in his genuine letters, although there is a rhetorical component:

- In Phlm 9 he describes himself as an "old man", i.e. over 50 years old. Then he would have been born around the turn of the times.

- In Gal 1,14-15 he compares himself with his peers; here we get the impression that he was a younger man (about 20 years old) when he was called/converted; this gives us a birth year of about 10 AD.

Both of these dates taken together indicate a birth year between 1 and 10 AD.

Origin

According to Acts 22,3 EU Paul came from a family of Pharisees from Tarsus in the Roman province of Cilicia at that time, a stretch of land in today's southern Turkey in the border area to Syria. This port city was then a major commercial center with a larger Jewish diaspora community, as existed in many Mediterranean coastal cities. "Little do we know what it meant to be a Greek-speaking Pharisee in Asia Minor at that time." (Ed Parish Sanders)

Jerome gives several examples of Paul using a Koine dialect typical of Cilicia in his letters, which was still in use in Jerome's time.

According to Acts Paul had the citizenship of the city of Tarsus (Acts 21:39 EU). From birth he was a Roman citizen according to Acts 16:37 EU; Acts 22:28 EU, a right that resembles an upper class characteristic for Tarsus in the early imperial period. It is conceivable that Paul's father had acquired the privilege of citizenship as a freedman of a Roman citizen: unusual for a Jew, but not impossible. Paul's family, for instance, could have been carried off by the Romans through captivity in war and sold into slavery at Tarsus. According to Jerome, Paul's parents came from Gischala in Galilee, one of the centers of resistance against the Romans during the first Jewish revolt. In any case, an original enslavement would most likely explain the fact that a Pharisaic family was found outside the Jewish heartland at all. This, however, would have raised the question for Paul's entire family of origin as to how they were going to stay away from pagan worship in the long run. A move to Jerusalem would have offered a way out here. According to the account in Acts, he later successfully invoked his civil law in conflicts over his mission - for example, when he was imprisoned in the temple in Jerusalem (Acts 21:37-40 SLT; Acts 22:23-30 SLT). However, at no point in his writings does he mention that he was in possession of these rights.

Luke introduces him with the Jewish first name Saul (Acts 7:58 EU; Acts 8:1, 3 EU), which is derived from Saul, Hebrew שָׁאוּל, the first king of Israel. Like the latter, his family came from the tribe of Benjamin (1 Sam 9:1 EU), which was considered the smallest of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. To explain the name Paulos (Greek παΰλος, Latin paulus or paullus means "little", Paulus literally "the little one") various hypotheses are discussed, among them that "the bestowal of the name may be connected with personal relations of Paul's father, for example with his patronus".

In contrast to the Hebrew name Saul, Paul is a name from the Hellenistic-Roman world. Paul himself always used only this name in his letters.

Luke casually speaks of "Saul who is also called Paul" only in Acts 13,9 EU, when Paul blinds the magician Elymas during a missionary journey in connection with the conversion of the governor of Cyprus Sergius Paulus. Saul, then, did not change his name because of his conversion and baptism into the Christian faith, as a popular opinion (cf. Acts 13:9 EU) and the well-known phrase from Saul to Paul suggest. Jews in the foreign environment and in the Diaspora often chose a second name that was immediately understandable to outsiders and sounded as similar as possible to their original name. That Paul adopted this custom can perhaps be seen as an indication that he knew how to move about safely as a Roman citizen, and that his opportunities in "preaching the gospel" (cf. 1 Cor. 15:1-4 EU) were thereby expanded. However, the name Paul was very rare at this time, but it was more common among the patrician gens of the Aemilians in Rome, for example.

"As to the name 'Paul,' it must be said that it was not very common among Romans, but extremely rare among non-Romans, especially in the Greek East, and does not occur at all among Jews elsewhere."

- Martin Hengel

Paul himself emphasized the complete change of character that happened to him through Jesus Christ, but he did not connect it with a change of name. He resolutely refused to misunderstand this change as an abandonment of his Judaism. Later he emphasized his Jewish descent again and again to his inner Christian opponents (for example Phil 3,5 EU):

"[...] one of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews, according to the law a Pharisee"

Education

Paul was already trained as a Torah teacher in his youth. He was a Pharisee and probably did not take up his scriptural studies in the Jewish diaspora, but in Judea and Jerusalem. Although born in Tarsus, according to Acts 22:3 EU, he grew up in Jerusalem and was taught there by the famous rabbi of the time, Gamaliel I. His letters show a solid knowledge of the Tanakh as well as Hellenistic rhetoric, forms of speech, and epistolary schemes. His writings use many terms of the Greek vernacular, especially those of the Stoa. This mode of expression was used and understood everywhere in the Mediterranean. Paul's language is greatly influenced by the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Scriptures. Occasionally he also resorted to the original Hebrew text with which he was familiar. The opposition of Judaism and Hellenism is outdated in the history of research; rather, Paul lived a biculturalism typical for his time, as he also knew Greek and Hebrew (no information is available about a possible competence in Latin, which he would have needed for his intended journey to Spain).

Before the Dead SeaScrolls became known, parallels of Palestinian Judaism were missing for many topics of Paul's letters, so that his insistence on being a Pharisee was incomprehensible. The Qumran scrolls now make it possible to understand Paul's conceptual world against its Jewish background in formulations such as "children of light", "works of darkness", "works of the law", "righteousness of God".

Paul later separated himself as a Christian from the wisdom cultivated in Diaspora Judaism (1 Cor 2:1-4 EU). Luke's stylized speech of Paul on the Areopagus (Acts 17 EU) is therefore judged as a later apologetic reinterpretation of genuine Pauline theology of the cross.

According to Jewish custom Paul learned the trade of a tent maker (Acts 18,3 EU). With this work he later earned his living as a missionary (1 Thess 2,9 EU and 1 Cor 4,12 EU). Thus he was not dependent on having to accept gifts from the Christian churches (Phil 4:14-18 EU and 1 Cor 9:12-18 EU). He could thus maintain the complete independence of his preaching and preach the gospel without remuneration. Ekkehard and Wolfgang Stegemann emphasize that Paul's social status according to his self-testimonies is completely different than according to Acts:

- According to the Acts of the Apostles he has the financial means to rent a school in Ephesus for his preaching work, and his own apartment in Rome. His work in the workshop of Priska and Aquila seems more like a "missionary tactical" approach.

- According to the letters Paul worked hard all day and before or after sunset (1 Thess 2,9), probably for a daily wage. His experiences of suffering with lack of food and insufficient clothing (e.g. 1 Cor 4,8ff.) fit with what is known about the daily life of ancient craftsmen.

So the historical Paul was probably "a member of the lower class above subsistence level."

Persecutors of Christians

How the Jew Paul came into contact with the first Christians is not clear from the book of Acts and the Pauline writings. He reports to the Corinthians that he persecuted the church of God (1Cor 15,9 EU). He openly mentions that he persecuted Christian churches in order to destroy them (Gal 1:13 EU). He zealously advocated the Jewish law (Phil 3:5-6 EU) and turned with hostility against the faith and way of life of the early Christians. He had made the attempt to take away the possibilities of the Christian churches to form and come together.

Until his conversion Paul represented Phariseeism, which demanded that proselytes (Gentiles who had converted to Judaism) were also to be circumcised (cf. Acts 15:5 EU). He saw himself as a "zealot for the law" (Gal 1:14 EU), who had fulfilled its regulations in an exemplary way also towards fellow Jews (Phil 3:6 EU). In this pursuit he became a fierce opponent of the Hellenistic Jewish Christians who missionized in the Jewish diaspora and made it easier for newly baptized Gentile Christians to follow the Torah by not circumcising them.

According to Luke Paul was a witness ("spectator and sympathizer", so Rudolf Pesch) of the tumultuous stoning of the first Christian martyr Stephen (Acts 7,58 ff. EU) in Jerusalem in an act of lynch law. He appeared as the spokesman of that group of Hellenists who were the first to start the mission to the Gentiles in the Jerusalem early church, rejected the temple cult and thereby came into conflict with the Sadducee priest aristocracy.

Paul, on the other hand, writes in Gal 1,22 EU that he was personally unknown to the churches of Judea, especially Jerusalem, until he traveled to Jerusalem three years after his conversion (Gal 1,18 EU). This contradicts Luke's account, which attributes to him an instrumental role in the persecution of Christians (Acts 22:4 EU). Paul's presence at the stoning thus remains questionable. Also, the appearance of a Paul endowed with powers of the high priest who dragged captured Christians bound before the Jerusalem tribunal (Acts 22:5 EU) seems unlikely within the Roman jurisdiction. Rather, Paul probably acted within the framework of the internal punitive power granted to the synagogue communities (scourging, banishment).

Vocation or conversion?

Paul himself describes the appearances of Jesus several times (Gal 1,15-19 EU; Phil 3,7-12 EU; 1 Cor 15,8-9 EU; 2 Cor 4,1.5-6 EU). God had already decided before his birth to reveal his Son to Paul and to call him to be an apostle to the nations (Gal 1:15 EU). He emphasizes that he followed his commission for three years and only then visited the early church in Jerusalem (Gal 1,17-19 EU). There is some evidence that he took over the already fixed original Christian confession formula with the list of resurrection witnesses, which he quotes in 1 Cor 15,3-7 EU and adds his own calling vision in verse 8.

Paul, then, by virtue of his vocational appearance, places himself among the resurrection witnesses reported to him by the eyewitnesses on his first visit to Jerusalem. The formulaic expression ōphthē (ὤφθη 'was seen', 'appeared') refers to visions which, as in Jewish apocalyptic, were experienced and passed on as God's revealed anticipation of end-time events (for example Dan 7:1-14 EU). For Paul here concluded his famous chapter on the resurrection of the dead, a belief he shared with Pharisees, Zealots and Essenes.

God's calling, the knowledge of Jesus Christ as the Son of God, the special commission for the mission to the nations and the certainty of the end-time raising of the dead formed an inseparable unity for Paul. He therefore emphasized that the gospel he preached was "not of human kind" (Gal 1,11 EU), but a message directly revealed by God.

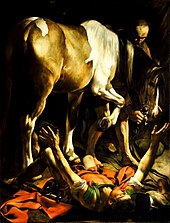

The book of Acts describes the calling of Paul (Acts 9:1-18 EU), the "Damascus experience", as the conversion of the persecutor of Christians. Paul hears on the way to Damascus - surrounded by a heavenly light - the voice of Jesus who asks him why he is persecuting him. He then loses his sight, is led to Damascus, is healed of his blindness there, and is baptized. Paul himself describes the experience in a biographical note in Gal 1,15-16 EU not as a conversion experience, but emphasizes the revelation and calling experience.

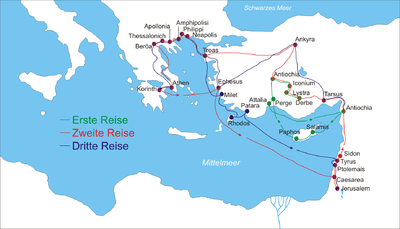

Mission trips

→ Main article: Missionary journeys of Paul

According to his self-understanding as an apostle to the nations, i.e. as a missionary among non-Jews, Paul wanted to spread the gospel of Jesus Christ as far as possible. He and his companions lived as itinerant missionaries who "in a certain (apocalyptic) haste and restlessness" (Norbert Brox) wanted to reach as large areas as possible by heading for the larger cities. The newly founded churches were then largely left to themselves, because the missionaries moved away to found churches elsewhere.

The book of Acts reports several journeys of the apostle, which are usually divided into "missionary journeys", but this does not quite correspond to the account of the book of Acts.

In the "first missionary journey" he visited Cyprus together with Barnabas and his nephew and afterwards the home of the proconsul Sergius Paul[l]us, whose family lived in Antioch near Pisidia. Forced by persecutions, he also traveled to other cities and finally returned with Barnabas to Antioch on the Orontes. Historically, a period of 12 to 13 years can be assumed for this phase of life, which is stylized by Acts as a single journey; neither are letters of Paul from this time known, nor did he comment on it later (possible exception: Gal 1,21).

The "second missionary journey" consisted of a trip to the churches in Galatia founded in the first journey and then to Greece, a longer stay in Corinth and then a trip to Jerusalem and Antioch on the Orontes. Luke describes the latter only briefly; this journey, together with the beginning of the "third missionary journey," forms a brief account of a journey from Corinth to the East and back to Ephesus, which was visited briefly on the outward journey. During the second missionary journey Paul wrote the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, which consequently is his oldest preserved writing.

The "third missionary journey" mainly consisted of a three year stay in Ephesus. This was followed by a round trip through Greece and a trip to Jerusalem, where apparently a collection mentioned in Paul's letters should be delivered (but Luke does not mention this). Paul's plans were to continue on to Rome and from there to mission the western Mediterranean as far as Hispania (Rom 15:22 f. EU). But in Jerusalem he was arrested by the Roman authorities and after a long time he was transferred to Rome where he probably suffered martyrdom.

A comparison with the Pauline letters shows that Paul probably made other journeys not mentioned in Acts. But we can only make assumptions about the details.

On his journeys Paul was accompanied by others; the epistles of Paul and the book of Acts name among others Barnabas, Timothy, Titus, Erastus and Silas. The goal of the missionary journeys was to build Christian churches. As soon as these were able to organize themselves independently, Paul traveled to the next city. The Christian churches in the urban centers became the starting point for further missions in the hinterland. Paul kept letter contact with the important churches; in the letters he deepened the Christian doctrine of faith and addressed problems and current issues.

Suffering and persecution

Paul often describes personal suffering in his letters, which he interprets as a consequence of his proclamation of Christ. According to this he repeatedly met with strong rejection by Jews and Gentiles, which sometimes led to "rebellion": Thus he survived various physical confrontations, attempts of stoning and scourging (cf. 2 Cor 11,24 f. EU; Acts 14,19 EU). This may have permanently affected him physically. As a Roman citizen he could have avoided mistreatment; either the information in Acts about this citizenship is to be judged as unhistorical, or Paul concealed his social status because he wanted to suffer for Christ; possibly he would not have been believed either: "An identity card to be carried in the pocket at all times did not exist then."

Gal 4:15 EU could refer to an eye ailment. In 2 Cor 12,7 EU Paul speaks of a "thorn in the flesh" and "angel of Satan, who must beat me with fists lest I exalt myself". By ancient Greek σκόλοψ skólops is meant, on the one hand, the stake, and on the other, any kind of "troublesome foreign body," e.g., splinter, thorn, spike. This is taken by many exegetes to indicate a disease that occurs in fits and starts with violent, stabbing pains. Suggestions are: chronic rheumatic disease, arthritis, depression, epilepsy, malaria, ocular migraine. Ulrich Heckel suggests trigeminal neuralgia. Largely based on the biblical description of Paul's conversion (Acts 9:1-9 EU), Hartmut Göbel states that the criteria for migraine (IHS code 1.1) are fulfilled:

- Duration of 4-72 hours if untreated (Paul was sick for three days);

- Pulsating pain (see above: "hitting with fists");

- Day activity made difficult (Paul had to be led);

- Reinforcement during normal physical activity (Paul lay down);

- Nausea, vomiting (Paul fasted);

- Photo- and phonophobia (perception of blinding light).

His unsteady lifestyle, especially the long journeys, had provided trigger factors for migraine attacks.

Perhaps Paul alludes to the Septuagint in 2 Cor 12:7 EU with the key word "thorn": "Then there shall be no more in the house of Israel a thorn of bitterness, neither a sting of pain from them that dwell round about them, and have offended them in their honor." This text, the ancient Greek translation of Ez 28:24 EU, is not about sickness, but about an unpleasant situation created by personal attacks.

Prison Stays

Paul was imprisoned several times. Two of his letters were written during a stay in prison (Philippians, Philemon). The book of Acts mentions a short imprisonment in Philippi (Acts 16,23 EU), and a longer stay in Jerusalem and Caesarea. Since the Romans did not know longer prison sentences, but only pre-trial detention and very short stays like in Philippi, it is unlikely that Paul was in captivity for another longer time. From 2 Cor 1:8 f. EU it is better not to read a stay in prison, and other passages in Paul's letters probably refer to the imprisonment in Caesarea or Rome.

In the Epistle to the Romans, the last of the genuine Pauline Epistles, Paul showed concern that he might be persecuted by Jews but also rejected by Jewish Christians during his planned journey to Jerusalem to deliver a collection to the early church there (Rom 15,30 ff. EU). As already at the apostles' convention, where this collection had been imposed on him for the approval of his Gentile mission, Paul obviously wanted to get the personal approval of the early church leaders for the completion of his life's work, the long planned mission also in the west of the Roman Empire. His concern had been well-founded since his departure from Corinth (Acts 20:3 EU): at that time, Paul and his companions chose the overland route via Macedonia and did not board a ship to Palestine until they reached Asia Minor, in order to avoid a planned attack by his Jewish opponents (Acts 20:14 EU). The personal delivery of the collection of money was supposed to strengthen the cohesion of Jewish and Gentile Christians, which was endangered by the increasing pressure of Palestinian Judaism on the early Christians and the turning away of some Gentile Christians from their Jewish roots.

Capture and Roman trial

According to his fear Paul was accused by Diaspora Jews in Jerusalem that he had brought a Gentile into the temple: According to the valid Sadducee Torah interpretation this was punishable by death, which the Romans allowed for such religious offenses. The occasion for this accusation was a ransom ceremony for Nazirites, which Paul wanted to pay according to Jewish custom, in order to demonstrate to the Jews his loyalty to Judaism. To protect him from Jewish lynching, the Roman guard intervened and took him into protective custody (Acts 21:27-36 EU). After a legal dispute of several years, during which Paul proclaimed the message of Christ to the Roman governors and appealed to the emperor as a Roman citizen (Acts 25,9 ff. EU), he was finally brought captive to Rome to present his legal claim.

The book of Acts does not report anything about the end of Paul. Luke used the context to insert dramatic scenes of judgment and Paul's speeches (Acts 20-25) into the account. Their purpose is disputed among today's exegetes. Perhaps Paul actually traveled to Hispania after his release.

Suspected martyrdom in Rome

According to a note first reported in the 1st Epistle of Clement (beginning of the 2nd century), Paul was martyred just like Peter. In the Acts of Paul, written at the end of the 2nd century, it is said that he was executed by the sword in Rome under Emperor Nero. Possibly he met his death in the course of Nero's persecution of Christians in 64. As a Roman citizen he would have been spared crucifixion.

His tomb is said to be in Rome under the church of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. Italian archaeologist Giorgio Filippi claims to have recovered it in June 2005. Excavations under the basilica led by Vatican archaeologists produced a Roman sarcophagus. Previously, it had been assumed that the tomb had been destroyed in a major fire at the basilica in 1823. In 2009, the bone remains found were radiocarbon dated to the first to second centuries. In addition, purple linen and blue cloth decorated with gold were discovered in the stone sarcophagus.

Beheading of St. Paul, ceiling fresco (1768) in Söll (Tyrol)

Missionary journeys of Paul (modern map)

Malta, Valletta: St. Paul's Column

The Conversion of Paul by Caravaggio 1600

Theology

Paul's theology is elaborated in his epistles (especially Romans and Galatians). He adopted the belief of the early Jerusalem church that Jesus of Nazareth was the Messiah (ancient Greek Χριστός Christós, German 'the anointed one') and savior of mankind expected in the Jewish tradition. In contrast to Jesus, Paul did not place the heavenly Father, but the risen Saviour and Mediator Jesus Christ at the centre of his preaching. He taught that with the giving of His Son God had also taken the unclean Gentile nations into His covenant, but in contrast to the "people of the first covenant" only by grace. The only thing necessary to accept this gift of love, he said, was faith in the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. The observance of the Jewish Torah was waived for the believing Gentiles. At the same time, however, they were subject to the chosen people of God. With this he laid the foundation for the separation of Gentile Christianity from Judaism.

See also: Pauline Theology

Basic Features

According to Udo Schnelle, transformation and participation are at the heart of Pauline theology: God did not leave the crucified Jesus of Nazareth in the status of death and remoteness from God, but gave him the new status of God-likeness. This line can then be extended further into the past: Jesus already had pre-existent this closeness to God, but gave it up, went the way of the cross, and returned to closeness to God. According to Paul, man can participate in the transformation of the Christ from death to life.

Whoever affirms the sentence: Christ died "for me" (Gal 2,20 EU) belongs to the group of the redeemed. Therefore Paul also rejects the adoption of the Jewish laws (circumcision among others). For it is not through the observance of laws, but through faith in the saving act of Christ that a person is redeemed. This does not mean that Paul gives all laws freely; instead there is a "law of Christ" (Gal 5 EU; Rom 13 EU) that every believer fulfills.

Crucial for the understanding of Paul's theology is the unconditional expectation of the end time. God will save those who turn to the faith in the saving act of Christ. With this, an important change has taken place in the history of religion: As a Jew, Paul was convinced that the one who fully observes the Jewish law will be saved. Since his call to be an apostle to the Gentiles, Paul has placed a completely different emphasis: it is no longer the observance of the law that saves, but faith. One does not have to be a Jew to be saved. From this follows an urgent command for Paul: All, also the Gentiles, must be informed about it. Paul wants all people to hear the message that faith in Christ saves them.

With this Paul did not want to dissolve Judaism. He only wanted to save the Gentiles, the Gentiles in the sense of that time. Paul allowed the primacy of Judaism to continue (Rom 9-11 EU). But the Gentiles were included in the circle of the saved since the Christ event, as long as they accept faith (Gal 3-5 EU).

Eschatology

Whoever believes in the saving act of Christ is righteous before God according to Paul. Salvation is certain for those who believe. But how is this salvation expressed? For Paul it is a completely new existence that the believing person receives (1 Cor 15 EU). Already influenced by the Holy Spirit in this world, the believer can expect the resurrection after death, which is to be understood as fellowship with Christ, laying aside the "flesh". At present, then, the believing Christian is already in communion with God through the Holy Spirit; for the future, completed redemption is pending. In Christ, believers have entered the new eon (Rom 6 EU), which is expressed for the individual Christian in the gift of the Spirit (Rom 8:23 f. EU). Nevertheless the individual Christian in his mortality remains attached to the old eon, but can live in the eschatological hope of fundamental newness (Rom 8,29 EU), which will come with the return of Christ for all believers and the whole creation of God.

The salvation event

Paul emphasized in Romans (3:27-28 EU) that faith in God's action in Christ's death and resurrection saves from ruin and death regardless of law-keeping or good actions. The importance of faith in Jesus Christ is also emphasized in Gal 2:16 EU, Phil 3:8-14 EU, and Rom 5:1 EU. But Paul also points out the practical-ethical consequences of faith (e.g. Gal 5,6 EU).

Paul is convinced that Christ died "for us". Since God does not cause anything that is not necessary, this death of Christ must have been necessary. It was necessary for the redemption of men. It is in this sense that the apostle's statement, "out of the law shall no man be justified," is to be understood: The redemption of man is possible through faith alone in the saving act. It is not possible out of the law alone. For if it were possible in this way, the death of Christ would not have been necessary according to this view.

The central question of justification by faith in Pauline theology is also exemplified by the example of Abraham (Gal 3,6-14 EU), who is praised by God in the Old Testament as an example of the righteous. However, the Jewish law is introduced later. For Paul, Abraham is the example of becoming righteous before God, even without the Jewish law. The law has above all the function of a protection against sin. But with the sending of Christ the power of sin has fallen and Christ is the fulfillment of the promise of salvation to Abraham.

In contemporary theological research, however, the exact meaning of Paul's statement "by works of the law no one is justified" is highly disputed. Luther had thought that Paul was saying that any attempt to fulfill the law would be a kind of self-righteousness, but today it is rather assumed that Paul wanted to point out the nullity of the law for the attainment of salvation: Whether I fulfill the law or not, it means nothing for salvation. Alternatively the following theses are held:

- The law no longer has a salvation function because there is now Christ (according to Ed Parish Sanders).

- The law has no salvation function, because God also wants Gentile believers to be under salvation (according to James Dunn).

- The law has never had a salvific function (according to Michael Bachmann).

Ethics

Paul is of the opinion that the law given by God cannot lead to salvation. Nevertheless it is a good, holy and righteous law for Paul. Because through the act of faith man is freed from the power of sin and enabled to fulfill the law of Christ. The basis of the law is the love commandment of Christ. No basis on the other hand are external rituals like circumcision.

Marriage and sexuality

Paul rejects sexual permissiveness and prostitution, which he encountered in rich Corinth, as "fornication". Intercourse with a prostitute defiles one's own body, which as the temple of God is the highest value beyond death and therefore in need of protection (1 Cor 6,13 EU). With this he is directed against those who refer to Greek ideals and think that "everything is permitted to me", and counters, "but not everything is useful". Fornication cannot be assigned a special position. Like marriage, the God-ordained unity of man and woman, extramarital sexual intercourse also unites to one body and thereby defiles the body of Christ (1 Cor 6,16 EU).

Those who could not completely abstain from sexuality, like the unmarried, perhaps widowed Paul, should enter into marriage in order to turn away from fornication (1Cor 7:2 EU). Paul emphasizes the value of marriage as a unity provided for in creation that is a part of the body of Christ. Both partners have the common body and are thus dependent on each other (1Cor 7:4 EU), the husband being the head of the wife, just as Christ is the head of the husband (1 Cor 11:3 EU). He does not reject existing marriages with unbelievers because the "unholy" partner can be saved by the believing partner (1 Cor 7:12-14 EU). Paul rejects divorces on the basis of Jesus' prohibition of divorce, unless the initiative comes from the non-Christian partner (so-called Pauline privilege, 1 Cor 7:15 EU). The preservation of the marriage unit is Paul's top priority. However, if the divorce is final, reconciliation should be achieved or the woman should remain celibate (1 Cor 7,10 f. EU).

Unmarriedness is a gift that is not possible for everyone. Whoever has this gift must seize the opportunity and not be deterred by opposition (1 Cor 7,7 ff. EU), as it was the case at the time of Paul against unmarried women. This also applies to widows, who do not have to comply with the obligation to remarry. However, marriage could also be a gift.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who is Paul the Apostle?

A: Paul the Apostle was a Messianic Jewish-Roman writer and rabbi who was also known as Saul of Tarsus.

Q: What is Paul the Apostle often called?

A: Paul the Apostle is often called Saint Paul.

Q: What is the Pauline epistles?

A: The Pauline epistles refer to thirteen books of the Bible that Paul is believed to have written.

Q: Who were the letters addressed to in the Pauline epistles?

A: The letters in the Pauline epistles were addressed to churches and Christians.

Q: Why did Paul write the letters in the Pauline epistles?

A: Paul wrote the letters in the Pauline epistles to encourage the churches and Christians, to help them understand Christian teaching, and to help them to live Christian lives.

Q: What is the religion of Paul before he converted to Christianity?

A: Before converting to Christianity, Paul was a Messianic Jew.

Q: When did Paul the Apostle live?

A: Paul the Apostle lived from 2BC to 67AD.

Search within the encyclopedia