Paul Hindemith

![]()

Hindemith is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Hindemith (disambiguation).

Paul Hindemith (* 16 November 1895 in Hanau; † 28 December 1963 in Frankfurt am Main) was a German composer of modern music (New Music). In his early creative period he shocked classical concert audiences with provocatively novel sounds (abrupt rhythms, glaring dissonances, incorporation of jazz elements), which earned him the reputation of a "citizen shocker". During the National Socialist era, his works were banned from performance, to which he finally reacted by emigrating, first to Switzerland, then to the USA. In the meantime, his compositional style developed towards a neo-classical style, which dealt with classical forms such as the symphony, sonata and fugue in a new way. In doing so, he distanced himself from the Romantic image of the artist as a genius inspired by inspiration and saw the composer and musician more as a craftsman. The emphasis on craftsmanship is also reflected in his theoretical writings, especially his instruction in composition. His theoretical system can be briefly described as free tonality, distinct from both traditional major-minor tonality and Schoenberg's twelve-tone atonality. He advocated "Gebrauchsmusik" (music for use) and saw it as the composer's duty to face social challenges and not to compose purely as an end in itself.

Hindemith particularly embodies the type of a universal musician who is equally adept in theory and practice. For example, he had rich experience as an orchestral (violin and viola) and chamber musician (as violist in the Amar Quartet). As a conductor (especially of his own works) he profited from his absolute ear and his largely professional mastery of all common orchestral instruments.

Paul Hindemith at the age of 28 (1923)

Paul Hindemith 1945, during his exile in the USA

Live

As the son of the house painter Rudolf Hindemith and his wife Sofie (née Warnecke), Hindemith came from a working-class family. He spent his early childhood in Rodenbach near Hanau. From the age of three to six, Paul Hindemith lived with his Hindemith grandparents in Naumburg am Queis in Silesia. In 1900 the family moved to Mühlheim am Main, where Paul completed his elementary schooling and received his first violin lessons. In 1905 he moved with his family to Frankfurt am Main; there he finished elementary school at the age of fourteen.

His family roots lie in Silesia. He came from an old-established Silesian family of merchants and craftsmen from the districts of Jauer and Lauban. His father Rudolf was born in 1870 in Naumburg am Queis, Silesia. He left his homeland as a young man and settled in Hanau around 1890, where he worked as a house painter. His father had his three children, Paul, born in 1895, sister Antonie (Toni), born in 1898, and brother Rudolf, born in 1900, taught music from an early age and had them perform under the name "Frankfurter Kindertrio". He gave them the education that had been denied to himself despite his musical disposition. His son Rudolf Hindemith, who found recognition as a cellist at a very early age, later also took up the profession of conductor and composer, but stood in the shadow of his famous brother Paul. His father, despite his advanced age of 44, enlisted as a war volunteer in 1914 at the beginning of the First World War. He was killed as an infantryman in hand-to-hand combat in the Battle of Champagne at Souain-Perthes in September 1915.

Childhood and competition of two brothers

As children, the two highly musical brothers Paul and Rudolf (1900-1974) were the family's figurehead; in their youth they began to play music together professionally in the Amar Quartet, one of the leading groups in the new music scene of the twenties. The younger Rudolf (cello) soon dropped out because he often felt left behind Paul, switched to the genre of brass band music and jazz and, unlike Paul, remained in Germany as a conductor.

Musical career

Paul had been learning the violin since the age of nine. Following a recommendation from his violin teacher Anna Hegner, he attended the Hoch Conservatory from 1908 and studied in Adolf Rebner's violin class. From 1912 he received composition lessons from Arnold Mendelssohn and Bernhard Sekles, with whom Theodor W. Adorno also studied. During the summer holidays he played in spa orchestras in Switzerland; in 1913 he was engaged as concertmaster at Frankfurt's Neues Theater.

From 1915 to 1923 he held the position of concertmaster at the Frankfurt Opera. Hindemith was transferred to Alsace during the First World War on 16 January 1918 as a military musician in an infantry regiment. From April his unit was stationed in northern France and Belgium, where Hindemith experienced the horrors of war. He was discharged from military service on 5 December 1918.

In the Amar Quartet, founded in 1921, he sat at the viola desk until 1929. In 1923 Hindemith fulfilled the wish of the pianist Paul Wittgenstein for a piano concerto for the left hand. However, the pianist did not perform the work. It was not until more than 80 years later, following the surprising discovery of the score in 2002, that the work was premiered by the Berlin Philharmonic in 2004.

One of Hindemith's favourite pianists at the time was the wife of the Frankfurt art historian Fried Lübbecke, Emma Lübbecke-Job, who had already performed his Quintet in E minor (Opus 7) in 1918 with the Rebner Quartet (see above); he dedicated his Kammermusik No. 2 (Opus 36) to her in 1924.

In the same year he married the musician Gertrud Rottenberg, daughter of the conductor of the Frankfurt opera orchestra Ludwig Rottenberg and granddaughter of the former mayor of Frankfurt Franz Adickes.

Hindemith came into contact with the new medium through his friend and brother-in-law, the radio pioneer and then director of the Frankfurt station, Hans Flesch, from 1924. On Flesch's initiative, Hindemith subsequently wrote a number of commissioned works for radio, including the musical audio picture Der Flug der Lindberghs (The Flight of the Lindberghs) in 1929, a joint production with Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. The Berlin Hochschule für Musik appointed Hindemith professor of composition in 1927. From 1929 Hindemith also taught at the Neukölln Music School, founded in 1927.

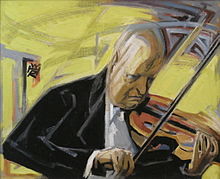

The composer's circle of friends included the Frankfurt painters Reinhold Ewald (1890-1974) and Rudolf Heinisch (1896-1956). Ewald, who lived in Hindemith's neighbourhood during his childhood, designed title pages for scores (for example Sancta Susanna). Hindemith remained close friends with Heinisch until his death. Heinisch was also his best man, drew his Amar Quartet and painted Paul Hindemith about fifteen times between 1924 and 1956. His best-known painting of Hindemith, which had been in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt since 1929, hung in the Nazi exhibition "Degenerate Art" in 1938 in the category "Technically Skilled, Sentiments Judaized" and was subsequently destroyed as "unusable".

In the meantime, several of his works were (premiered) at the ISCM World Music Days and the Donaueschinger Musiktage. When Hindemith's 3rd String Quartet Opus 16 was premiered there by the Amar Quartet in 1921, it earned him the reputation of Europe's most influential and respected modern musician at the age of barely thirty. He was artistic director of the Kammermusiktage from 1923 to 1930, together with Heinrich Burkard and Joseph Haas, and made it one of the most important forums for new music. From this time on, Hindemith was one of the most important, but also most controversial, trendsetters of contemporary music in Germany.

Unusual music

For example, many of his choral works and songs still sound rough and unusual today and are - for example for choirboys - an interesting challenge. The texts he chose, which include many Christian poets in addition to Luther, also aroused rejection during the rise of National Socialism. The majority of his nearly 100 piano songs have remained undiscovered by performers to this day.

Hindemith's rather short-lived interest in the new electric instruments, which were in the first stages of development, falls into this period. First confronted with Jörg Mager in Donaueschingen in 1926, he became particularly interested in the development of the trautonium and encouraged its first presentation in Berlin in 1930. His interest accompanied the development until his 40th birthday, when his third and at the same time last composition for this instrument was performed for the first time by Oskar Sala.

Confrontation with the "Third Reich

In the 1930s Hindemith increasingly shifted his musical activities as a violist to other European countries, and concert tours took him to the USA from 1937. His work was increasingly hindered by the NSDAP. NS supporters did not doubt Hindemith's musical ability as a "great man of his time", but agitated against his "intolerable attitude". Adolf Hitler had already complained about the fifth picture of the opera Neues vom Tage in 1929. Parts of his works were removed from the programmes under the verdict of "cultural bolshevism" or as "degenerateart". As early as 1934, his works were banned from broadcasting on German radio. In the same year, Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels publicly described him as an "atonal noisemaker". Wilhelm Furtwängler's article Der Fall Hindemith (The Hindemith Case) in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung on 25 November 1934 effectively drew attention to Hindemith's situation: No one of the younger generation had done as much for the reputation of German music abroad as Hindemith. One could not afford to do without him. Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels reacted angrily.

As a sign of his solidarity with those persecuted by the regime, Hindemith played pieces by Bach on the viola on Christmas Eve 1933 in the Berlin remand prison Moabit, where his brother-in-law Hans Flesch, among others, was imprisoned at the time. Between 1934 and 1935 he lived in Lenzkirch, Baden, where he completed Mathis der Maler.

In 1935, under protest from his students, Hindemith went to Turkey on behalf of the German Reich government to establish the Ankara Conservatory. He had taken leave of absence from his position. From 1936, the performance of his works was forbidden, which led him to resign his position in 1937. The climax of his confrontation with the Nazi system was the National Socialists' "Degenerate Music" exhibition in 1938. In it, explicit reference was made to the Jewish ancestry of his wife Gertrud.

Emigration and return

In 1938 Hindemith and his wife went into exile, initially to Switzerland. The couple left the country again in 1940 to take exile in the USA. They settled in New Haven, Connecticut, where Hindemith taught as a professor at Yale University until 1953. In 1940 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and in 1947 to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1946 he received American citizenship.

At the end of the 1940s Hindemith made a career as a conductor, mainly for classical music. Worldwide tours had him performing in musical centers, such as with the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras. In 1950 Hindemith accepted an honorary doctorate from the Free University of Berlin; he also became an honorary member of the Vienna Konzerthausgesellschaft. 1950 Honorary member of the International Society for Contemporary Music ISCM. In 1951 he received the Bach Prize of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg.

At the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM World Music Days) Hindemith is one of the most frequently performed composers. The following works by him were performed successively at the ISCM festivals: 1923 in Salzburg Clarinet Quintet op.30 (world premiere), 1924 in Salzburg the String Trio op. 34 (world premiere), 1925 in Venice the Chamber Music No. 2 op. 36/1, 1926 in Zurich the Concerto for Orchestra op. 38, 1928 in Siena the Suite for Piano op. 37, 1934 in Florence the Heckelphon Trio op. 47, 1938 in London excerpts from Mathis der Maler, 1942 in San Francisco the Symphony in E-flat! , 1946 in London the String Quartet in E-flat, 1957 in Zurich the Chamber Music No. 1 op. 24/1 and 1964 in Copenhagen the Concert Music op. 41. Hindemith also performed as a chamber musician at the ISCM World Music Days 1922-24 with the Amar Quartet.

Alternating with Yale, Hindemith also taught in Zurich from 1951, where a chair was established for him. In 1953 he moved back to Switzerland and lived in his villa La Chance in Blonay near Vevey on Lake Geneva. In 1954 he conducted the unofficial debut of the Concentus Musicus Wien with Monteverdi's Orfeo at the Vienna Konzerthaus. In 1955 he was honoured with the Goethe Plaque of the city of Frankfurt am Main and awarded the Wihuri Sibelius Prize. In 1962 he received the Balzan Prize for Music and was inducted into the American Philosophical Society.

In 1957 Hindemith ended his teaching career and then went his own musical way as a composer and conductor. He devoted himself more to conducting and went on tours to Asia and the USA. After the premiere of his last composition in Vienna on 12 November 1963, Hindemith returned first to Blonay to the Villa La Chance. On his birthday he fell seriously ill and was admitted to the Marienhospital in Frankfurt am Main at his own request. There he died of pancreatitis on 28 December.

Students

Hindemith trained numerous composers. However, there were also critical voices about his pedagogical work. The Austrian composer Gottfried von Einem was critical:

"Hindemith was a really great master, we all know that, but he was a terrible teacher. Nothing came out of it because he tied people to him. So the opposite of Blacher."

Peter Ré, who studied with Hindemith at Yale University, comments in an interview:

"He was very selective about his students. I was fortunate to be one of them. [...] We were very worried about whether we were able to answer questions that he had for us, because he was ahead of us in a way. And we learned a lot of new things that we never had before in our back training. It was a wonderful experience but he was a very tough teacher and he would certainly harshly criticize you if you didn't know what you were doing. [...] He was very clear in correcting us when we showed him what we were doing. We were always amazed at his knowledge. [...] You loved and you hated him. It could be terribly difficult with him. But the fact that he selected you was always a safety thing."

"He was very particular about his students. I was lucky enough to be one of them. [...] We were very concerned about whether we could answer questions that he asked us because he was ahead of us, in a sense. And we learned a lot of new things that we never had in class before. It was a wonderful experience, but he was a tough-as-nails teacher, and he certainly criticized you harshly if you didn't know your stuff very well. [...] He clearly corrected us when we showed him our work. His knowledge always amazed us. [...] One loved him and one hated him. He could be terribly difficult to deal with. But the fact that he had chosen one always gave one a sense of security."

- Peter Ré

The Hindemith researcher Gerd Sannemüller also stated:

"Inwardly preoccupied with the expansion of his strict tonal theory and unwilling to compromise, he [Hindemith - T.E.] left his students little room to work more freely. The exclusive attitude to this tonal system was often seen as a restriction of the possibilities for artistic development; Adorno uses the harsh word 'Gleichschaltung' for this. A distance from students who had other ideas was therefore at times unmistakable in Hindemith's 13-year North American teaching career."

- Byeongso Ahn, South Korean violinist, conductor, composer and pedagogue

- Howard Boatwright, US-American composer and musicologist

- Siegfried Borris, German composer

- Arnold Cooke, British composer

- Carlos Ehrensperger, Swiss composer

- Dietrich Erdmann, German composer

- Lilli Friedemann, German violinist and improviser, inventor of group improvisation

- Lukas Foss, American pianist and composer

- Zoltán Gárdonyi, Hungarian composer and musicologist

- Harald Genzmer, German composer

- Guillermo Graetzer, Argentine composer, music educator and musicologist of Austrian origin.

- Artur Grenz, German composer and conductor

- Bernhard Heiden, German-American composer

- Andrew Hill, US jazz pianist and composer

- Walter Kraft, German composer and organist

- Felicitas Kukuck, German composer

- Werner Kaegi, Swiss composer

- Heinrich Konietzny, German bassoonist and composer

- Walter Leigh, British composer and pianist

- Ernst Hermann Meyer, German composer

- Hans Friedrich Micheelsen, German composer and organist

- Konrad Friedrich Noetel, German composer

- Hans Otte, German pianist, composer and music mediator

- Franz Reizenstein, German-Jewish composer and pianist

- Oskar Sala, German composer and physicist

- Hans-Ludwig Schilling, German composer

- Ruth Schönthal, German-American composer and pianist

- Robert Strassburg (1915-2003), American composer/educator

- Josef Tal, Israeli composer

- Tan Xiaolin, Chinese composer

- Johannes Paul Thilman, German composer

- Friedrich Tilegant, German conductor

- Heinz Zeebe, German conductor

- Rudolf Zink, German composer

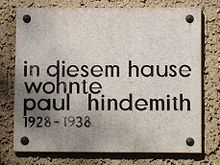

House in Lenzkirch with memorial plaque (2010)

Memorial plaque in Lenzkirch

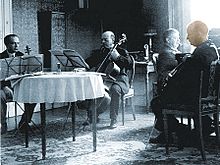

Paul Hindemith (right) making music (with viola) in Vienna in 1933. f. l. t. r.: Bronisław Huberman (violin), Pau Casals (cello), Artur Schnabel (piano)

Paul Hindemith with viola (1956), painting by Rudolf Heinisch

Amar Quartet (1922) from left to right: Maurits Frank, Licco Amar, Walter Caspar and Paul Hindemith

Hindemith's residence 1923-1927 in the Kuhhirtenturm in Frankfurt am Main

Commemorative plaque on Berlin's Brixplatz

Stamp for the 100th birthday 1995

Hindemith Awards

To date, two Paul Hindemith Prizes have been endowed by the Hindemith Foundation, to which the Hindemith Music Centre also belongs, in honour of Paul Hindemith: the Hindemith Prize awarded within the framework of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival since 1990 and the Paul Hindemith Prize of the City of Hanau since 2000.

Search within the encyclopedia