Pantheon, Rome

The Pantheon (Ancient Greek Πάνθειον (ἱερόν) or Πάνθεον, from πᾶν pān "all", "total", and θεός theós "God") is an ancient building in Rome that was converted into a church. As a Roman Catholic church, its official Italian name is Santa Maria ad Martyres (Latin Sancta Maria ad Martyres).

After a form of name Sancta Maria Rotunda, which has been in use since the Middle Ages, the building in Rome is also colloquially called La Rotonda.

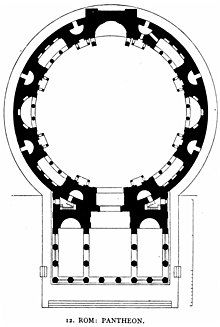

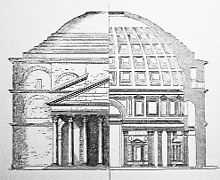

Possibly begun under Emperor Trajan around 114 AD and completed under Emperor Hadrian between 125 AD and 128 AD, the Pantheon had the largest dome in the world by internal diameter for more than 1700 years and is generally considered to be one of the best-preserved structures of Roman antiquity. The Pantheon consists of two main elements: a pronaos with a rectangular floor plan and temple façade to the north, and a circular, domed central structure to the south. A transitional area mediates between the two parts of the building, the resulting spandrels of the interfaces were used for staircases.

Built on the Field of Mars, the Pantheon was probably a sanctuary dedicated to all the gods of Rome. The historian Cassius Dio reports that statues of Mars and Venus as well as other gods and a statue of Gaius Iulius Caesar, who was included among the gods as Divus Iulius, were erected there. Which gods were to be worshipped here is, however, disputed, especially since it is not completely clear whether the Pantheon was originally a temple or an imperial representative building that served secular purposes despite its elements borrowed from sacred architecture.

On May 13, probably in the year 609, the Pantheon was converted into a Christian church after the Emperor Phocas had given it to Pope Boniface IV, and it was consecrated to St. Mary and all the Christian martyrs. Masses are celebrated in it, especially on high feast days. The church was elevated to the title of deaconry by Pope Benedict XIII on July 23, 1725. Pope Pius XI transferred it on 26 May 1929 to the church of Sant'Apollinare alle Terme Neroniane-Alessandrine, 400 metres away. Santa Maria ad Martyres has the title of basilica minor and is attached to the parish of Santa Maria in Aquiro. The building belongs to the Italian State and is maintained by the Ministry of Cultural Assets and Tourism.

The influence of the Pantheon on the history of architecture, especially in modern times, is enormous. Today, the term Pantheon is also generally applied to a building in which important personalities are buried, which stems from the later use of the Roman Pantheon.

Facade of the Pantheon

Floor plan of the Pantheon completed under Hadrian

Dome of the Pantheon seen from the hill Gianicolo on the right bank of the Tiber river

The Pantheon by night

Building description

The Pantheon of Agrippa

Agrippa had his building erected on the Field of Mars on the site that had previously belonged to Pompey, then to Marcus Antonius. Other building projects planned and financed by him were built in the immediate vicinity, such as the Agrippa Baths or the Saepta Iulia, a large assembly hall, the construction of which Caesar had already begun. Agrippa's Pantheon anticipated the basic features of Hadrian's complex. It had a broad rectangular pronaos of ca. 44 m × 20 m. In the south a round building adjoined it. The older pronaos, the remains of which were discovered during excavations carried out in 1892/1893 as well as in 1996/1997, was situated at the same place as the successor building, but was somewhat wider. In former times it was assumed that Agrippa's building was oriented exactly the other way round compared to Hadrian's building existing today and referred to the Augustus Mausoleum lying to the north, the results of the excavations in the 1990s suggest that under Hadrian there was no new orientation of the new building, but Hadrian's architect followed the Augustan Pantheon in this respect. This had either a ten-columned front or an eight-columned one between protruding antennas. Statues of Augustus and Agrippa were placed in the pronaos. In the area of the rotunda a circular wall was found during the excavations, which enclosed the same area as the later circular building. In contrast to the successor building, however, this part of the building was not roofed over. It was a circular building or open courtyard about 44 m in diameter, surrounded by a wall about two metres high and paved with slabs of pavonazzetto (a marble from the quarries of Dokimeion), white marble and travertine. Its interior design is unexplained. Cassius Dio tells us that statues of the gods (he mentions Mars and Venus by name) and a statue of Caesar were placed here.

This building of Agrippa was damaged by fire in 80 and is listed among the buildings restored by Domitian. The complete redesign in Hadrianic times was preceded by an extensively destructive fire in 110 under Trajan.

The Pantheon of Hadrianic times

The forecourt

North of the Pantheon today is the Piazza della Rotonda with the Egyptian obelisk erected there. In Hadrian's time, the street level was between 1.50 and 2.50 m below today's level. Leading to the north entrance of the building was a square measuring about 60 × 120 m, paved with travertine slabs and enclosed at right angles on the west, north and east by porticoes. The halls were supported by columns of grey granite and were based on a series of five steps of marble (giallo antico). The pronaos of the Pantheon was connected to the porticoes on the west and on the east by a fountain basin of Prokennesian marble. The two statues of the river gods Tiber and Nile, which today are placed in the Capitoline Square, may have originally served here as fountain figures.

Due to the modern development of the area north of the Pantheon, the archaeological evidence for the entire forecourt is rather sparse. Thus, for example, the exact location and appearance of the northern portico remain pure speculation, since no findings exist in this regard. A structure that was located in the center of the square can no longer be clearly identified today.

The Pronaos

The pronaos in front of the rotunda in the north gives the impression of a typical Roman podium temple. It has a rectangular ground plan measuring 33.10 × 15.50 metres and is only accessible from the northern side. While today a three-step staircase runs along almost the entire north side of the pronaos, its podium, which is around 1.50 metres high, was originally only accessible via two staircases, each 7.30 metres wide. The north façade is divided by a colonnade of eight unchannelled Corinthian columns of grey Egyptian granite from Mons Claudianus with column bases of marble, while the remaining columns of the pronaos were worked in red granite. The short sides are two columns deep. The inscription on the frieze mentioning Agrippa dates from Hadrianic times. A second inscription still mentions a restoration of the building in 202 AD by the emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla. The gable field above is empty today, but in antiquity it was probably decorated with an eagle holding the Corona civica in its fangs.

The interior of the pronaos is divided into three naves by four unchannelled Corinthian columns, reminiscent of the typical Etruscan-Roman temple. The floor is covered by slabs of marble, granite and travertine, forming simple circular and rectangular patterns. The two side aisles end in the south with an apse, where statues of Augustus and Agrippa were probably originally placed. The south wall of the pronaos is richly decorated with marble slabs and is divided by Corinthian marble pilasters. The wooden beams of the roof truss were covered with bronze plates in ancient times. The central nave, which is wider than the side naves, ends with a 6-metre-high bronze door, which could be the reused door from Agrippa's building. Through it one enters the rotunda.

From the outside one can see that the gable roof of the pronaos rises up to the height of the dome attachment point. On the narrow sides of the pronaos, the architrave, frieze and geison are continued up to the rotunda, and the lateral colonnade ends in marble pilasters. Above the pronaos, the building has no further incrustations and is only divided by a tympanum between two cornices.

The Rotunda

The most important building component of the Pantheon is a vaulted circular structure with an internal diameter and height of 43.30 m (i.e. 150 Roman feet). The load-bearing masonry consists of opus caementicium, a cast masonry, with bricks as lost formwork interrupted by balancing layers. The balancing layers consist of travertine and tuff in the lower area, bricks in the middle area and mostly tuff in the upper area, so that the weight decreases with the height. In the dome the aggregate consists of light lapilli tuff. The load-bearing walls rest on a 7.50 m wide and 4.60 m deep annular foundation of cast masonry with travertine as balancing layers. The exterior façade of this rotunda is simple in design and is articulated only by three cornices. Clearly visible are semi-circular relief arches made of bricks, which absorb the enormous pressure of the dome. There are no traces today that would indicate that the façade would have been covered with marble slabs in ancient times.

The rotunda conveys a completely different sense of space than the pronaos. Its typical structure of a rectangular Roman podium temple is contrasted by the circular interior dominated by the dome, which has no model in Roman temple architecture in terms of dimensions. The original, rich decoration of the interior with different coloured stone from all parts of the Mediterranean region has been preserved in its basic features to this day. The floor picks up the design in the pronaos and is covered with a pattern of large squares and circles of porphyry, grey granite and giallo antico (the much sought-after yellow marble from Simitthu) framed by bands of pavonazzetto. The surrounding wall is divided into two decorative zones. In the lower zone, the wall is divided by seven niches and the entrance portal. Only the barrel vault above the entrance and the calotte of the southern niche cut into the upper wall zone. The niches have alternating semicircular and rectangular ground plans. They are framed by corner pillars with Corinthian capitals. Two fluted Corinthian columns are set into each niche. Except for the southern niche, there are three aedicules in each of the other niches. In antiquity, statues of deserving Romans from the Republican period may have been placed here. There are also aedicules between the individual niches. The exposed parts of the wall in the lower decorative zone are covered with a geometric pattern of circular and rectangular fields of different coloured stone. Towards the top, the lower zone ends with a richly decorated entablature. The incrustation of the attic zone above is not preserved in its original form today, but can be reconstructed in a short section according to drawings by Baldassare Peruzzi and Raphael. It was covered with a similar, but more delicate pattern than the lower zone.

A dome forms the ceiling of the building. It has a diameter of about 43.45 m at approximately half the height of the stitch. Completed into a sphere, it would pass about half a metre below ground level. The Roman concrete of the dome was made of light volcanic tuff and pumice mixed together. To further save weight, the dome is articulated by five concentric rings of 28 cassettes each, with the cassettes of each ring getting smaller and smaller towards the top. The division of the cassettes does not correspond to that of the wall below, but is slightly offset. Originally, the inside of the dome was painted and each cassette bore a bronze, possibly gilded star or rosette. At the apex of the dome is a circular opening nine metres in diameter, the opaion, which is the only source of light in the interior apart from the entrance portal. In order to drain off the rainwater that penetrates through it, the floor of the domed hall slopes slightly towards the centre and is provided with 22 small drains at convenient points. On the outside, the wall below the dome is higher than in the interior, so that the dome - seen from the outside - does not represent a complete hemisphere. On the outside, the dome is covered with bronze plates, the antique originals of which, however, are no longer preserved.

Sectional view of the rotunda of the Pantheon, James Ferguson, A History of Architecture in All Countries, London 1893

_-_Dome.jpg)

View into the dome of the Pantheon

_entrance_door.jpg)

Entrance area with 6 meter high bronze door

The Pantheon in Piazza della Rotonda with the Obelisco Macuteo in the foreground

Portrait of Agrippa (Louvre)

Portrait of Hadrian (Museo Nazionale Romano)

Interior of the Pantheon today

Interpretation

The name Pantheon, which is only attested a few times for antiquity, suggests a consecration to all or at least several gods. Exactly which deities were worshipped in the pantheon remains unclear. Statues of gods erected within the sanctuary are mentioned by Cassius Dio (53, 27), but he only mentions Mars, Venus and the Divus Iulius by name. One possibility would be to reconstruct the worship of all celestial or weekly gods, i.e. also of Sol, Luna, Mercurius, Jupiter and Saturnus. It is also conceivable that Agrippa had planned a sanctuary for Augustus and his family, the Julian-Claudian dynasty, as well as their divine ancestors and patrons. This is supported by the erection of a statue of Caesar, Augustus' deified adoptive father, in the sanctuary, as mentioned by Cassius Dio. A comparable complex, the Nemrut Dağı, is known from the small Hellenistic kingdom of Kommagene, but here in connection with royal burials. Cassius Dio further reports that Augustus ordered that his statue be placed not in the sanctuary but outside, in the pronaos. A divine veneration of his person during his lifetime would hardly have fit the image of the primus inter pares that Augustus had propagated of himself.

A round, open courtyard, enclosed by a wall and entered via a gateway with a rectangular ground plan, is already known as a sanctuary from Roman architectural history from the time before Augustus. It seems to be a particularly venerable old Italian type of building, which is why Agrippa chose it for his monument. By adding the temple-like pronaos and the unusual size, however, he gave it a monumentality that comparable older structures had not possessed. The same approach of combining ancient Italic building forms with precious materials or monumental dimensions is also found in other buildings from the time of Augustus, such as the Ara Pacis or the Mausoleum of Augustus.

When Hadrian had the Pantheon rebuilt, he refrained from having his name affixed to the building and named Agrippa as the builder in the inscription on the frieze of the Pronaos. This is entirely in accordance with the policy of Hadrian, who was thus able to enact his virtuous reserve. There is no reason to suppose that the Hadrianic Pantheon did not serve fundamentally the same purpose as its Augustan predecessor. However, the now chosen construction form of the domed central room finds no models in the temple architecture of the time. Wolfram Martini therefore put forward the thesis that Hadrian's Pantheon was not originally a sacred building, but an imperial assembly hall, an audience and court room, as part of an imperial forum. He draws parallels to domed halls in imperial palace architecture, for example to Nero's Domus Aurea, but does not include Agrippa's predecessor building and its significance in his thesis. The spherical dome depicting the heavens, the opaion as an opening to the heavenly bodies, the light of which travels over the dome in the course of the day, and the seven niches in the walls indicate that the Hadrianic pantheon was used as a temple for the celestial deities. The opaion also establishes in the new building the direct connection to the open sky, which had been an important element in Agrippa's pantheon and which threatened to be lost through the erection of the dome.

Since the late 1990s, research approaches outside classical antiquity and building research have claimed that the metrics of the building follow the attempt of neo-Pythagorean philosophy to integrate the sciences of the quadrivium - i.e. arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy - into a harmonious whole. The Pantheon would thus be an image of the Pythagorean cosmos in mathematical implementation.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Pantheon?

A: The Pantheon is a building in Rome that was originally built as a temple to the gods of Ancient Rome.

Q: When was the Pantheon rebuilt?

A: The Pantheon was rebuilt about 126 AD during Hadrian's reign.

Q: What is the design of the Pantheon attributed to?

A: The design of the Pantheon is sometimes credited to Trajan's architect Apollodorus of Damascus, but it may also have been Emperor Hadrian's architects who designed it.

Q: Has the Pantheon always been used?

A: Yes, since it was built, the Pantheon has always been used.

Q: What is the Pantheon used for today?

A: Since the 7th century, the Pantheon has been used as a Roman Catholic church.

Q: What is notable about the Pantheon's dome?

A: The Pantheon dome is the largest dome made mainly of unreinforced concrete. It does, however, contain other materials and is the oldest standing domed structure in Rome.

Q: What is the meaning of the term "pantheon"?

A: The term pantheon is sometimes used for a building where well-known dead people are buried, but in this case, it refers to the Temple of all the gods.

Search within the encyclopedia