Pangolin

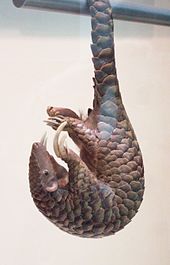

The pangolins or pine cones (Manidae) are a family of mammals that also forms its own order, the Pholidota. The family consists of three recent genera with eight species, four of which live in East, South and Southeast Asia and four in sub-Saharan Africa. They are insectivorous animals specializing in ants and termites, adapted to this mode of feeding by digging claws, a tubular snout with toothless jaws, and a long tongue. Unique among mammals is their body covering of large, overlapping horny scales. Pangolins live on the ground or in trees, depending on the species, and are usually nocturnal. However, their exact lifestyle is poorly understood. They prefer forests as well as partly open landscapes in lowlands and middle mountain heights. In case of threat they can curl up into a ball. This characteristic is also referred to by the original Malayan word peng-guling, whose variation pangolin is mainly used in English and French as a colloquial term for a pangolin.

The present family name Manidae was introduced in 1821. In the early history of research in the 19th and early 20th centuries, pangolins were considered close relatives of anteaters and armadillos. With the former they share the toothless mouth and the long tongue. It was mainly the lack of teeth that led to the creation of a taxon called Edentata, in which all three animal groups were listed for a long time. It was only in the mid-1980s that modern molecular genetic studies revealed that the pangolins were more closely related to the carnivores. The similarities with anteaters and armadillos are therefore based on convergence. The loss of teeth, but also the specialized way of life further causes that pangolins are rarely fossilized. The earliest representatives of the Manidae are known from the Pliocene about 5 million years ago, but forms close to them already appeared in the Middle Eocene about 47 million years ago.

All eight current species of pangolins are considered to be more or less endangered and are internationally protected. The main reasons for the threat are the sale of the meat as an exotic food speciality on the one hand and the use of the scales and other body parts in local ritual customs as well as in traditional Chinese medicine on the other. As a result, pangolins are not only intensively hunted, but are also among the most illegally traded mammals worldwide.

Features

Exterior physique

Pangolins have an elongated body with short limbs, small, pointed head and long tail. The head-torso length varies depending on the species, in smaller representatives such as the white-bellied (Phataginus tricuspis) and the long-tailed pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla) it is between 25 and 43 cm; the largest species is the giant pangolin (Smutsia gigantea) with 67 to 81 cm. The tail becomes again between 25 and 70 cm long. In the tree-dwelling pangolins the tail exceeds the rest of the body length, in the others it is of equal or shorter length. Weight varies from 1.6 to 33 kg, with males usually larger than females. Fossil Manis palaeojavanica occurred in the Pleistocene of Southeast Asia, a species that reached about 2.5 m in total length, representing the largest pangolin species known to date.

The head of the pangolins is small and conical in shape. The eyes are also small and protected by bulging, gland-free eyelids. Ear pinnae are absent in African species, and often only a thickened crest is present in Asian species. The nose is closable by a skin fold (plica alaris), which is advantageous when the animals insert their snouts into insect burrows to feed.

The eponymous feature is the body covering, unique among mammals, of large horny scales covering the top of the head, the trunk, the outer sides of the limbs (in some species without the forearms) and the upper and lower sides of the tail. Only the face, abdomen, and inner side of the limbs are unscaled and have gray, coarse skin covered with white, brown, or black hairs. In African pangolins the scales on the back of the tip of the tail are irregular or arranged in pairs, while in Asiatics they are always regular in only one row. On the underside of the tail tip, however, arboreal pangolins have a free area covered with horny skin; in ground-dwelling ones the armor is closed. Single hairs grow between the scales of the dorsal armor only in Asian species.

The limbs appear short and stout, each ending in five toes (pentadactyl). The forelegs show adaptations to a digging way of life, in that the middle three fingers are provided with long, curved claws, of which the middle one is again considerably larger. In contrast, the claws of the first and fifth fingers are reduced in size and are not used when digging. The hind legs are stronger and somewhat longer, and the five toes also have claws. In general, the forefoot claws of ground-dwelling pangolins are longer and less curved than those of tree-dwelling ones; the latter, in turn, have much longer hindfoot claws, which aid in locomotion in the trees.

Skull features

The skull reaches lengths between 6 and 16 cm. It is generally conical in shape with a tubular rostrum that narrows somewhat towards the front and is slightly elongated. Since the food is not chewed, the masticatory musculature is regressed, whereby only a few bone elevations are formed as muscle attachment points. This makes the skull appear very smooth, making it one of the most simply built skulls within the mammals.

A striking characteristic is the not fully formed zygomatic arch, a feature that the pangolins share with the anteaters of South America, which also specialize in ants and termites, and is often considered an adaptation to this diet. However, closed zygomatic arches sometimes occur in some pangolins, such as the Chinese pangolin. Other general characteristics are found in the elongated nasal bones and the large frontal bones compared to the parietal bones.

Teeth are completely absent, the mandible is formed only as a simple bone brace with weakly developed, posteriorly pointing and spherically shaped joint ends, which allow little room for mandibular movement. The symphysis of the mandible forms a flat surface over which the tongue can slide. However, as a characteristic of all pangolins, a pair of bony, conically pointed projections occurs at the posterior end of the symphysis, bearing resemblance to a canine tooth.

Scale armour

The scale armour, together with the rest of the skin, makes up about a quarter to a third of the total body weight. It consists of 160 to 290 individual scales, of which just under half are on the tail. They are mobile and overlap each other like roof tiles. They are arranged in rows, the number of which varies between 13 and 25 on the trunk. The coloration of the scales ranges from dark brown to olive green to yellowish. They are triangular to V-shaped; large scales have lengths and widths of 7 to 8 cm. Longitudinally directed ribs are found on the surface, and they also have sharp margins. The largest scales are usually on the back with the tip pointing backwards. When rolled up, the sharp ends stick out similar to a half-open pine cone. The scale armor does not so much protect against ant or termite bites or skin parasites as it does against injuries caused by larger predators or while burrowing underground.

The scales are keratinized formations of the epidermis, which sit on rearwardly bent protuberances of the dermis. In cross-section, three layers can be distinguished: The upper dorsal plate (dorsal plate) occupies about one-sixth of the thickness and consists of oblate, highly keratinized cells. The intermediate plate, which occupies the largest space, is formed of less flattened, keratinized cells. The ventral plate (abdominal plate) forms the underside of the scale and is only a few cells thick. All three plates form from different epidermal germinal areas. The absence of filaments indicates that the scales do not correspond to agglutinated hairs, as previously thought. They can rather be compared in structure with the fingernails of primates, and like these they grow constantly, which compensates for wear. This also distinguishes them from the scale skin of the pangolin, which sometimes has to be changed annually.

It is assumed that the scaled carapace was formed early in the evolution of pangolins - the oldest evidence comes from Eomanis from the Middle Eocene, about 47 million years ago, found in the Messel Pit in Hesse. Possibly a scaling of the tail was formed first, which could be seen as a homologous development to some representatives of rodents like the house mouse or the nutria or also the tree shrews, only later a complete armouring of the body took place.

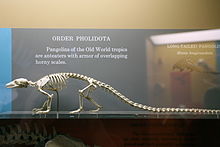

Skeletal features

The number of vertebrae varies from species to species and ranges from 48 in the steppe pangolin (Smutsia temminckii) to over 70 in the long-tailed pangolin. Overall, the spine consists of 7 cervical, 12 to 15 thoracic, 5 to 6 lumbar, 2 to 4 sacral, and 21 to 50 caudal vertebrae, depending on the species. The animals can curl up well, because the pelvis is very short and the ilium is bent outwards and the lumbar vertebrae are elongated. The tail vertebrae have chevron bones on the underside, which serve as an attachment surface for the powerful tail muscles, as the tail is wrapped around the body like a shield when curled up. The sword process at the rear of the sternum is enlarged to the pelvic region and serves as an attachment site for the complex tongue muscles.

Above all, the humerus is particularly strongly developed for the digging and tree-climbing way of life. It has a very broad elbow joint and - typical for pangolins - a strong crista deltoidea, which embraces the shaft as a bony crest and functions as an attachment point for the shoulder muscles. On the femur, the third trochanter tertius, another muscle attachment point on the shaft, is set far down at the ends of the joints and is thus barely visible. In very primitive Pholidota this is clearly higher and prominent on the shaft. A further special characteristic are the respective last limbs of the toes of the front and hind feet (in each case phalanx III), which show an elongated form and possess deep notches at the end, in which the claws adhere.

Internal organs

Very characteristic is the worm-shaped tongue covered with sticky saliva, with which the food is taken. It can be up to 70 cm long in the giant pangolin and stretched out up to 25 cm, in the Chinese pangolin it becomes up to 41 cm long with a diameter of up to 1.1 cm. Its complex musculature consists of longitudinal and radial muscle fibers. When at rest, the anterior part of the tongue lies curled up in the mouth, the surface roughened by conical papillae in the anterior region, with mushroom-shaped taste buds at the tip. The tongue is not connected with the hyoid bone as in other mammals, but with the posterior part of the sternum by an external muscular system, which is partly homologous to the hyoid muscles. The hyoid bone has a different function in pangolins: it is used to scrape off insects adhering to the tongue at the entrance to the esophagus. The salivary glands are enlarged and extend into the thoracic and axillary regions.

The muscular stomach performs the mechanical crushing of insects. It is equipped with horny and stratified squamous epithelium, which protects it from the bites and poison of ants and termites. The greatly enlarged pyloric muscles grind the swallowed food and are provided with ossified spines (pyloric spines) for this purpose for better comminution - small pebbles are also swallowed. The gastric glands are very long and tubular; they form glandular packets which empty through a central duct towards the pylorus. The entire intestinal tract reaches a length of 5.2 m and a diameter of about 1 cm in the Chinese pangolin. It is tubularly coiled and shows no differences between the small and large intestines, only in some individuals is there a slight thickening or coiled formation in the posterior region, possibly indicating the transition from small to large intestine. A caecum is not formed. Pangolins have anal glands whose scent secretion is used for communication and possibly defense. Females have a two-horned uterus (uterus bicornis). Males have a small penis but no scrotum - the testes lie under the skin.

The brain is very simply built and small, for example in the Malayan pangolin it makes up only about 0.2 to 0.5% of the body weight. Only the olfactory bulb is well developed, accordingly the sense of smell plays an important role in the search for food and in communication with conspecifics. According to the structure of the brain - here mainly related to the cerebellum - Asian species are somewhat more primitive than African.

Skeleton of a long-tailed pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla)

Single scales of the scale carapace

Dissected Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla): The large digging claws of the front feet and the muscular tail, which can carry the weight of the animal, can be seen.

Pangolin (Manis crassicaudata)

Skull of the white-bellied pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis)

Distribution and habitat

Pangolins live in sub-Saharan Africa and in South, Southeast Asia and southern East Asia. In Africa, their range extends from Senegal and Sudan to South Africa. In Asia, they are distributed from Pakistan and Nepal to India and the Indochinese Peninsula to southern China and from the Malay Peninsula to Borneo and the Philippines. The pangolins thus primarily inhabit tropical regions.

Their habitat includes a variety of landscape types, such as riparian and swamp forests, but also rainforests, open savannahs and scrublands, and mosaic vegetation areas. They also tolerate secondary landscapes used by humans, such as plantations, garden landscapes and farm areas, which must contain enough shelter in the form of trees or rocks and burrows. However, the animals avoid human settlements and farmlands and are sensitive to pesticides. Thereby the pangolins use lowlands and highlands, in the Nilgiri Mountains in India the Near Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata) has been recorded up to altitudes of around 2300 m. The basic prerequisite for the presence of the pangolins is, apart from a dense underground vegetation, sufficient food resources of ants and termites as well as water.

Due to the diverse use of landscapes and partial specialisation on different food groups, overlapping of the individual ecological niches used by sympatric species is rare. In individual cases, however, an increased niche formation takes place. For example, the long-tailed pangolin increasingly uses water areas in regions with the simultaneously occurring white-bellied pangolin. The Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) continues to live in northern Vietnam, where the Malayan pangolin (Manis javanica) is also common, principally at altitudes above 600 m. Also with other highly specialized insectivores, for example the African aardvark (Orycteropus), there is hardly any overlap in the same used landscapes due to the strong niche formation.

Distribution of the pangolins Species in Asia pangolin pangolin Malayan pangolin Palawan Pangolin Species in Africa Tumbleweed White-bellied Pangolin Giant Scaled Animal Long-tailed Pangolin

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a pangolin?

A: A pangolin (or scaly anteater) is a mammal that lives in Africa and Asia. It has scales on its skin, which makes it the only mammal with this adaptation.

Q: What do pangolins eat?

A: Pangolins eat ants and termites, which they catch using their tongues. They do not eat anything else.

Q: How long is the gestation period of a mother pangolin?

A: The gestation period of a mother pangolin is between 120 and 180 days.

Q: What are the main predators of pangolins?

A: The main predators of pangolins are wild cats, hyenas and humans.

Q: How does a pangolin defend itself from predators?

A: When threatened, a pangolin can curl up into a ball with its overlapping scales acting like armour while it tucks its face under its tail. The scales are also sharp, providing extra defence from predators.

Q: Why are they smuggled into China?

A: Pangolins are smuggled into China on the black market because their scales are used as an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine.

Q: Are they endangered species?

A: Yes, they are critically endangered species due to being hunted and trafficked all across Asia and Africa for their scales, meat and medical properties.

Search within the encyclopedia