Ottoman Empire

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/NAME-German

The Ottoman Empire (Ottoman دولت علیه İA Devlet-i ʿAlīye, German 'der erhabene Staat' and from 1876 officially دولت عثمانيه / Devlet-i ʿOs̲mānīye / 'the Ottoman State', Turkish Osmanlı İmparatorluğu) was the empire of the Ottoman dynasty from ca. The term Ottoman Empire, which is obsolete in German-speaking countries but still found in English- and French-language literature, derives from variants of the Arabic form of the name Uthman of the dynasty's founder Osman I.

It emerged at the beginning of the 14th century as a regional dominion (Beylik) in northwestern Asia Minor in the border region of the Byzantine Empire under a leader of presumably nomadic origin. This broke away from dependence on the Rum Seljuq Sultanate, which had fallen under the domination of the Mongol Ilkhanate after 1243 and had forfeited its power. Capital was from 1326 Bursa, from 1368 Adrianople, finally since 1453 Constantinople (Ottoman Kostantiniyye; since 1876 officially called Istanbul).

At the time of its greatest expansion in the 17th century, it stretched from its heartlands of Asia Minor and Rumelia northward to the area around the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, and westward far into southeastern Europe. For centuries, the Ottoman Empire claimed a major European power role politically, militarily and economically alongside the Holy Roman Empire, France and England. In the Mediterranean, the empire fought with the Italian republics of Venice and Genoa, the Papal States and the Order of Malta for economic and political supremacy. From the late 17th century until the late 19th century, it wrestled with the Russian Empire for dominance over the Black Sea region. In the Indian Ocean, the empire challenged Portugal in the struggle for primacy in long-distance trade with India and Indonesia. The history of the Ottoman Empire is closely linked to that of Western Europe through its uninterruptedly intense political, economic and cultural relations.

In the Near East, the Ottomans ruled the historical heartlands of Islam: Syria, the area of present-day Iraq, and the Hejaz (with the holy cities of Mecca and Medina). In North Africa, the area from Nubia through Upper Egypt westward to the middle Atlas Mountains was under Ottoman rule. In the Islamic world, the Ottoman Empire represented the third and last major Sunni power after the Umayyad and Abbasid empires. After the Safavid dynasty in Persia had imposed Shia as the state religion, both empires continued the old inner-Islamic conflict between the two Islamic confessions in three major wars.

In the course of the 18th and especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, the empire suffered considerable territorial losses in conflicts with the European powers as well as through national independence efforts in its Romanian heartlands. Its territory was reduced to European Thrace and Asia Minor. Within the few years from 1917 to 1922, the First World War led to the end of the four great monarchies of the Hohenzollerns, Habsburgs, Romanovs and Ottomans, which had shaped the history of Europe for centuries.

In the Turkish War of Liberation, a national government under Mustafa Kemal Pasha prevailed; in 1923, the Republic of Turkey was founded as the successor state.

Concept of empire, political and social order

Devlet-i ʿAlīye - the sublime dominion

From its beginnings until the reforms of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was characterized by diverse forms of governance and a wide variety of relationships between the center and regional forces. In contrast to the linguistically, culturally or ethnically uniform nation state, the term world empire or empire is used for this organizational form of "state" power. According to Klaus Kreiser, this way of exercising power was less the result of a conscious political decision than an expression of the lack of means to organize such a large and diverse territory uniformly and centrally. Kreiser therefore speaks of the Ottoman Empire as an "empire against its will". The Islamic term "al-daula" (Arabic الدولة, DMG al-daula 'cycle, time, rule', Turkish devlet) is associated primarily with a "house" or dynasty, and thus with the person and family of the ruler, less with the institutions of a state administration. In the course of the centuries, state structures had developed more distinctly in the Ottoman Empire than in the rest of the Islamic world.

The House of Osman exercised its rule through the control of strategic points such as cities, fortifications, roads, and trade routes, as well as through its ability to claim resources for itself and demand obedience. In so far as in the course of imperial history different territories were added to the empire at different times, rule was not exercised uniformly everywhere, but varied from region to region. In the process, the empire had various options for action in the newly conquered territories: The subjugated territories could be fully incorporated or run as vassal states with varying degrees of allegiance, or even enjoy partial autonomy. In any case, loyalty to the person of the sultan, the payment of tribute and the provision of troops were demanded.

Since the medieval and early modern empire lacked fast and effective means of communication, a standing army, and regular revenues in sufficient quantities to enforce a uniform central structure throughout the empire, the central government was dependent on the cooperation of local rulers. Relations with them were based on principles similar to those of the later colonial "indirect rule": the central government maintained independent relations with the regional rulers, who were entrusted with "state" tasks such as the collection of taxes and their payment to the state treasury, but rarely interfered in local administration. In contrast to the colonial model of rule, however, it was in principle possible for any Ottoman subject to rise to the social elite and up to the sultan's court in the capital. Historians such as Karen Barkey see this flexible and pragmatic ruling structure as one of the reasons for the empire's long existence under a single ruling dynasty.

The sultans organized their rule starting from Istanbul as the center in a form comparable to the modern hub-and-spoke model. In this way, the central government largely prevented regional forces from allying and acting against it. In the 16th and 17th centuries, this model of government proved its worth during several Celali uprisings. By the end of the 18th century and with the beginning of the 19th century, however, the rulers in the provinces (ayan or derebey) had gained extensive autonomy from the central government. In 1808, their political influence had reached a peak with the agreement of the Sened-i ittifak under Grand Vizier Alemdar Mustafa Pasha. De facto, the ayan and derebey at this time acted like local ruling dynasties with considerable military power. The authority of the sultan was limited only to Istanbul and its environs. The Balkan provinces in particular, with their large estates and commercial ventures, benefited from better links to the world market and only loose control by the central government. Pamuk suspects that it is therefore no coincidence that it was precisely in these provinces that the political disintegration of the Ottoman Empire began, with the Serbian independence movement from 1804 and the Greek Revolution of 1821.

In contrast, the empire sought to compensate for losses elsewhere. After regaining direct rule over Tripolitania, the Ottomans annexed Fessan as a base for further advance into the Sahara and sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, the Ottomans strengthened their control over Arabia and re-established direct rule over Yemen. In the same vein, the expansion of the Ottoman-dependent Egyptian dynasty of Muhammad Ali extended the borders of Egypt, and thus the Ottoman Empire, across Sudan into what is now Uganda, the Congo Basin, and what is now Somalia.

Other designations

In Western Europe, the country was also known as "Turchia" ("Turkey" or Turkish Empire) from the 12th century onwards, after the ethnic descent of the dynasty.

Society and administration

The social order of the empire followed military principles: The elite class of the askerî comprised the non-taxable ranks of the Ottoman military, members of the court and the imperial administration, as well as the spiritual elite of the ʿUlama'. Subordinate to these was the Reâyâ, which paid taxes and duties. For many centuries, Ottoman society was characterized by the coexistence of various ethnic and religious groups under the suzerainty of the sultan and the central government. High officials and important artists and craftsmen did not come only from the Islamic Turkish population, for Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and other groups contributed to the culture of the Ottoman Empire. In the last decades of its existence, a nationalism that was also understood in ethnic terms led to the demise of this tradition of coexistence that had been fruitful for centuries.

Sultan

→ Main article: List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire

At the center of power were the sultan (from Arabic سلطان, DMG sulṭān 'ruler') and his dynasty, whose values and ideals legitimized their rule, determined the organization, policies, and procedures within the administrative apparatus, and created the elites who worked within it. From the 15th century onward, the empire was organized as a sultanate patrimonial, as well as an order of estates, Islamic in its values and ideals, shaped according to the notion of a vast extended household with the sultan at its head. The sultan's rule was fundamentally bound only by the sharia (Turkish Şeriat or şer-i şerif, "the noble law"), within limits also by laws of his predecessors. A special interpretation of the sharia according to the Hanafite school of law also legitimized political power religiously.

Marriages of the sultans often served to consolidate foreign and domestic political alliances: Until about 1450, sultans mostly married women from neighboring dynasties, and later from the Ottoman elite itself. Children - and thus possible successors - were predominantly born of relationships with concubines. The mother of a ruling sultan (valide sultan) thus acquired a rank and political importance that did not correspond to her original social status. During the period of "female rule" from the end of the 16th to the middle of the 17th century, influential sultan mothers secured the power of the dynasty.

A division of inheritance of the empire was unknown. A male descendant of the sultan inherited the entire empire. Until the second half of the 19th century, there was no explicit and comprehensive regulation on succession to the throne; therefore, at the latest on the death of a sultan, there was often a dispute between his descendants. From about the end of the 14th century, an Ottoman prince (şeh-zāde) was given an Anatolian sandzak to administer at an age of about fifteen, so that he could gain experience in administrative matters and learn the art of government as a prince-stateholder (çelebi sulṭān) under the guidance and supervision of an educator (lālā). The sultan could try to influence the succession by giving his favored son the governorship nearest the capital. The victor in a succession dispute usually persecuted the losing brothers and relatives and had them murdered. This custom was considered problematic by the sultans themselves and their contemporaries: Selim I's first act as ruler was to order the execution of his brothers and all his nephews. In order not to force his son, the later Suleyman I, to do likewise, he refrained from fathering any more sons. The Selim-nāme of Şükri-i Bidlisi, the first of a series of historical works dealing with this period, had, among other things, the purpose of propagandistically downplaying the sultan's violent accession to the throne and his role in history. With Murad III. (from 1562 to 1574) and Mehmed III. (from 1583 to 1595), only the eldest sultan's sons were still appointed as presumptive successors in fact and not just nominally as governors (in Manisa), while the other princes, too young for governorship, remained locked up inside the Topkapı Palace. This ensured that the ruler-designate could ascend the throne uncontested and have his (half-)brothers, who were in the palace, executed without difficulty. Finally, after Mehmed III's accession in 1595, no princes were sent away at all, but were kept in the part of the sultan's palace originally called şimşīrlik or çimşīrlik (roughly 'boxwood garden') and later ḳafes 'cage'. In the event of an unforeseen change of power, for example in the case of Mustafa I after the death of his brother Ahmed I, the new sultan took office completely unprepared.

Central government

→ Main article: List of the Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire

Characteristic of the Ottoman elites was their recruitment from the ruled peoples. A hereditary nobility in the European sense was largely unknown, although there were influential families such as the Çandarlı, who provided several grand viziers such as Çandarlı II. Halil Pasha (vizierate 1439-1453). Until the end of the 16th century, many high administrative officials came from Christian families in Rumelia, who had been forcibly recruited in the course of the boy selection and, after their conversion to Islam, enjoyed a thorough education that qualified them for the highest offices of state.

As was common in many Islamic states, the sultan was assisted by a Dīwān of viziers. Several times a week the imperial council (Ottoman همايون ديوان İA dīvān-ı hümāyūn, German 'großherrliche Versammlung') met. In later times, the Dīwān was usually presided over by the grand vizier, rather than the sultan himself. The other viziers were also called 'dome viziers' (Kubbealtı vezirleri) after the domed hall in the Topkapı Palace where this assembly was held. The governors of Cairo, Baghdad and Buda also held the rank of vizier, and they were called "outer viziers". Since Suleyman I, the role of the grand vizier as the absolute representative (vekīl-i muṭlaḳ) of the sultan has been established. Representing the sultan, he became the head of the civil and military organization and supreme judge. In the event that the sultan did not lead a campaign himself, the grand vizier held the role of commander (serdār). Only the household of the grand vizier and the Islamic scholars were exempt from his command. Upon his appointment, the grand vizier was given the imperial seal (mühr-i hümāyūn, 'the exalted seal'). From 1654 he had his own residence, the High Gate (Ottoman پاشا قاپوسى İA Paşa ḳapusı, German 'Gate of the Pasha', later Ottoman باب عالی Bâbıâli, German 'High Gate', rarely also called باب اصفی / Bāb-ı Āṣefī).

The members of the military and administration were considered direct subjects (ḳul) of the sultan, who was obliged to support them, but also exercised direct jurisdiction over them. In this way, the sultans strengthened their rule. After the 17th century, the central government in the provinces lost its direct political influence to regional rulers (ayan or derebey), who could act largely independently as long as their loyalty to the sultan was not in question. The sultans thus remained the guarantors of political legitimacy. With reforms since the beginning of the 19th century, the government attempted to bring the administration and economy back under central control.

The Ottoman administration had two other important institutions: Court Chancellery and Tax Office. The Court Chancellery dealt with correspondence, which grew in volume over time, issued charters, and documented the decisions of the Court Council, which it published in the form of decrees (fermanen). The most important office was that of the nişancı, the tughra draughtsman. His task was to draw the tughra over important documents and thus authenticate the document. In accounts of European diplomats, this official is often referred to as the "chancellor." The scribes of the court chancellery were presided over by the reʾīsü 'l-küttāb, the chief scribe. All documents produced were registered in the central registry, the defterhane, which was under the direction of a chief registrar (defter emini).

The Ottoman Empire financed itself predominantly through taxes. As early as the second half of the 15th century, Mehmed II placed the financial officials (defterdars) directly under the Grand Vizier. The Defterhane was located in the Topkapı Palace right next to the room where the Council of State met. Among the most important duties of the defterhane was the quarterly payment of wages for the askerî. The head of the financial administration was the defterdar. At first there was only one defterdar; from about the time of Bayezid II a second was appointed to be responsible for Anatolia, while the first, the başdefterdar, retained responsibility for the European part of the empire. After the conquest of the Arab territories, a third was added, based in Aleppo, Syria. The officials of the financial administration used a special script (siyāḳat) for their records, which could only be read by the officials of the authority, and which was forgery-proof mainly because of the special numerical signs used.

Social elites

The ruling social elite in the Ottoman Empire was divided into four institutions: The official scholars of the empire (ilmiye), the members of the court (mülkiye), the military (seyfiye), and the administrative officials (kalemiye).

From the late 16th century onward, the Ottoman sultans appointed a head (mufti) of the ʿUlamā' in each eyalet, headed by the chief mufti or "shaykhülislam" (Turkish Şeyhülislâm) in Istanbul. In this way, the sultan was able to exert greater influence on the ʿUlamā', which formally remained superior to the sultan due to its privilege of interpreting the sharia. In the case of unwelcome decisions, the sultan could simply replace one mufti or the Şeyhülislâm with another. With the bureaucratization of the ʿUlamā' in the group of the Ilmiye, a further step toward the centralization of power in the person of the ruler had been taken.

Mahmud II's reforms further weakened the political influence of the ʿUlamā': the Şeyhülislâm was now given the position of a state official who had to follow instructions from the sultan. The newly established Ministry of Religious Endowments controlled the finances of the Vakıf endowments, thus depriving Islamic scholarship of control over significant financial resources.

Subjects, equality, "fatherland" in the 19th century

Until the reforms of the 19th century, subjects subject to levies were regarded as reâyâ ("flock"), from whom loyalty and obedience were expected. The Tanzimat decrees aimed to make all inhabitants of the empire equal in principle and to endow them with equal rights: The Gülhane decree in 1839 conceded legal security to all subjects, and the Hatt-ı Hümayun in 1856 replaced the term 'reâyâ' for the first time with 'tebaa' (from Arabic tabiʿ, 'belonging', 'dependent'). Reâyâ remained as a term only for non-Muslim subjects in the Balkans and unchanged in Arabic, there without reference to religious confession. Tebaa nevertheless described less the politically participating citizen or citoyen, but continued to serve to distinguish the subject from the sovereign, the sultan. The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 finally declared equality ('müsavet', from Arabic مساواة, DMG musāwāt 'fair treatment, equality') of all tebaa before the law. Since Islam remained enshrined in the constitution as the state religion, this was contrary to the principle of equality.

The new term "Osmanlı" was used for the first time in the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 to refer to all inhabitants, no longer just the elites. Based on the thoughts of European philosophers such as Montesquieu and Rousseau, Ottomanism defined membership in the Ottoman state politically, not ethnically or religiously. With the Tanzimat reforms, the term "vatan" (from Arabic الوطن, DMG al-Watan 'homeland, fatherland') came to refer to the empire. Vatan initially had more of a non-political, emotional meaning, similar to German terms. In 1850, for example, the district governor of Jerusalem called on all non-Muslims to contribute to the support of the poor and elderly, "since we are all brothers in the fatherland (ikhwān fīʿl waṭan)." From about 1860, it was used more frequently in the context of patriotism and sultan loyalty.

Rukiye Sabiha Sultan's wedding anniversary in 1920, from left to right: Fatma Ulviye Sultan, Ayşe Hatice Hayriye Dürrüşehvar Sultan, Emine Nazikeda Kadınefendi, Rukiye Sabiha Sultan, Mehmed Ertuğrul Efendi, Şehsuvar Hanımefendi.

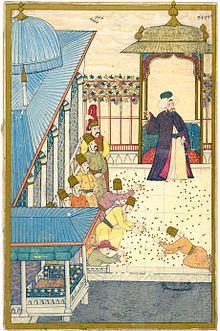

Sultan Ahmed III, Surname-i Vehbi, 1720, f.174b

Population and religion

Population

The Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic state. The total population of the Ottoman Empire is estimated at 12 or 12.5 million people for 1520-1535. At the time of its greatest spatial expansion towards the end of the 16th century, there were - though the uncertainty is enormous - about 22 to 35 million people living in the Ottoman Empire. Between 1580 and 1620, the population density rose sharply. In contrast to the Western and Eastern European countries, which experienced strong population growth after 1800, the population of the Ottoman Empire remained almost constant at 25-32 million. In 1906, about 20-21 million people lived in the empire's territory (which had been reduced in size due to territorial losses in the 19th century).

Migration

Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire was a transit space that offered a variety of opportunities for networking and identity formation in the interplay of identification and demarcation. Trade routes by sea and land connected distant territories. Cities served as hubs for trade and cultural exchange. As a rule, inhabitants of different religions, languages and ethnic origins lived in the cities and regions. Because of their connections to their places of origin, the inhabitants were able to maintain areas of communication and trade even beyond the borders of their dominions. At the same time, independent social structures and identities developed in the new place, often characterized by multilingualism.

The history of Constantinople offers an example of this: After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the heavily depopulated city had to be repopulated. This was done at the invitation of the authorities, but also through forced migration and deportation (sürgün). Muslims settled in the majority, but also Jews from the Balkans. From 1492 the Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain by the Alhambra Edict followed, after 1496/1497 also from Portugal. A decree of Sultan Bayezid II welcomed them. Armenians and Greeks continued to live in the city. In his historical work Künhü'l-aḫbār, the Ottoman historian Gelibolulu Mustafa Âlî (1541-1600) described how newly immigrated Turkish and Tatar tribes had mixed with the resident population, Arabs and Persians, as well as formerly Christian Serbs who had converted to Islam. The social elite, at least, saw themselves as "Rûmi".

Growing population pressure in certain regions or social unrest such as the Celali uprisings of the 16th and 17th centuries each triggered massive population shifts. Pastoral nomads, mostly Turkmen, Kurds or Arabs, migrated to western Anatolia and Cyprus, the Aegean islands or the Balkans in search of better pastures or under pressure from stronger nomadic groups. In addition, the Ottoman government pursued a policy of active deportations in order to get rid of unpopular populations or to repopulate an area that was important to the state. In the early 18th century, Muslim Bosnians fled from Hungary back to Bosnia. At the same time, the Ottoman administration sought to push Turkmen and Kurdish nomads to the border of Syria, where they would be settled as a counterweight to the Bedouins who were increasingly migrating to Syria in the 18th century. The Balkan wars were accompanied by devastating epidemics and famines that further reduced the population. In the 18th and 19th centuries, refugees from the Russian-conquered Balkan territories, Circassians, and displaced persons from the Crimea were admitted. The settlement of Albanian mercenaries on the Morea led to the flight of parts of the Greek population in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Ottoman administration repopulated these areas with Anatolian settlers, and a temporary exemption from the land tax (charaj) served as an incentive. By the end of the 18th century, oppression and exploitative taxation by local rulers led to a pronounced rural exodus. The French consul general de Beaujour reported that in the period from 1787 to 1797 there were only two rural inhabitants for every urban inhabitant in Macedonia. At the same time, the Western European population was divided 1:5-6 between town and country. Famines and natural disasters reduced the population in many parts of the country in the 18th century.

Religious communities

Until the second half of the 15th century, the empire had a Christian majority and was under the rule of a Muslim minority. As Sunni Muslims, the sultans followed the Hanafi school of law. Since the conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt in 1517, they also held suzerainty over the Hejaz and the holy Islamic cities. In the 18th century, this fact was invoked to justify the Ottoman Caliphate. In addition, Christianity (Orthodox, Armenian and Catholic), Judaism (see Sephardim), Alevism and Shiite Islam, Jesidism, Druze and other denominations and religious communities were represented in the empire.

In the late 19th century, the non-Muslim share of the population began to decline considerably - not only because of territorial reductions but also because of migratory movements. Muslims accounted for 60% of the population in the 1820s, gradually rising to 69% in the 1870s and then to 76% in the 1890s. By 1914, only 19.1% of the empire's population was non-Muslim, mainly Christians, and some Jews.

| Population distribution of millets in the Ottoman Empire in 1906, according to the census. | |||||||||

| Millet | Inhabitants | Share | |||||||

| Muslimea | 15.498.747–15.518.478 | 74,23–76,09 % | |||||||

| Greeksb | 2.823.065–2.833.370 | 13,56–13,86 % | |||||||

| Armenianc | 1.031.708–1.140.563 | 5,07–5,46 % | |||||||

| Bulgarians | 761.530–762.754 | 3,65–3,74 % | |||||||

| Jews | 253.435–256.003 | 1,23–1,24 % | |||||||

| Protestantend | 53.880 | 0,26 % | |||||||

| Andered | 332.569 | 1,59 % | |||||||

| Total | 20.368.485–20.897.617 | 100,00 % | |||||||

| Note: a The Muslim Millet included all Muslims including Turks, Kurds, Albanians and Arabs. | |||||||||

Muslims who were considered heretics, such as Alevis, Ismailis and Alawites, had a lower rank than Christians and Jews. In 1514, Sultan Selim I, called "the Grim" for his cruelty, ordered the massacre of 40,000 Anatolian Kizilbash (Shiites) whom he considered heretics, declaring that "killing one Shiite would bring the same reward in the hereafter as killing 70 Christians."

See also: Religion in the Ottoman Empire and Alevi Persecution in the Ottoman Empire

Reform of the Millet system in the 19th century

The Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane (1839) had guaranteed individual rights and thus implied the equality of all citizens of the Ottoman Empire. The Hatt-ı Hümâyûn of 1856 proclaimed the idea of a "heartfelt band of patriotism" ("revabıt-ı kalbiye-ı vatandaşî"), but challenged the resistance of Muslims in Syria and Lebanon, for example, who saw their privileged status guaranteed by the sharia endangered. With the reorganization of the millet system in the Edict of 1856, the Ottoman government reacted to the fact that more and more non-Muslim religious communities were claiming millet status for themselves, as well as to the corruption prevailing in the millets. New directives came into force in 1860-62 for the Greek Orthodox Church, in 1863 for the Armenian Church, and in 1864 for the Jews. On the one hand, the drafting of sets of laws (nizam-nāme) for the non-Muslim communities raised hopes for a general imperial constitution. On the other hand, however, the practice of separate legislation for individual religious communities disregarded the ethnic differences that formed the basis of the nationalist currents of the nineteenth century. As a result, the reform projects promoted political separatism rather than reinforcing the idea of a common Ottomanism ("osmanlılık").

In the clash of Enlightenment, Islamic and Turkish nationalist schools of thought, the cohesion of the various religious and ethnic groups, and ultimately the empire itself, broke down. The political dominance of the Young Turks led to a nationalist redefinition of citizenship and ultimately to the emigration, deportation, and genocide of groups that had been part of Ottoman society for centuries. In the 20th century, the 1915 Deportation Law triggered a resettlement campaign that eventually led to the Armenian genocide; the Greek population, which had been native to Asia Minor since antiquity, was also forced to emigrate in 1914-1923.

Ottoman Jews

Ethnological map 1910, the Ottoman Greeks in blue

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the official name of the Ottoman Empire?

A: The official name of the Ottoman Empire was the Sublime State of Ottomania (in Ottoman Turkish: دولت عالیه عثمانیه, in Turkish: Devlet-i Aliyye-i Osmâniyye).

Q: When did the Ottoman Empire exist?

A: The Ottoman Empire existed from 1299 to 1923.

Q: Who founded the empire?

A: The empire was founded by Osman I around 1299.

Q: When was it most powerful?

A: The empire was most powerful from around 1400 to 1600.

Q: Who was one of its most powerful rulers?

A: Suleiman the Magnificent was one of its most powerful rulers.

Q: How were conquered countries governed within the empire?

A: Conquered countries were governed by governors appointed by the Sultan with titles such as Pasha or Bey.

Q: What caused its weakening in later years?

A: In later years, the Ottoman Empire began to weaken due to internal and external factors such as economic decline and military defeats in World War I which ultimately led to its dissolution.

Search within the encyclopedia