Augustine of Hippo

![]()

Augustine is a redirect to this article. For the given name Augustine see Augustine (given name).

Augustine of Hippo, but usually without addition Augustine or Augustin, occasionally also Augustine of Thagaste or (probably not authentic) Aurelius Augustine (* 13 November 354 in Tagaste, today Souk Ahras/Algeria; † 28 August 430 in Hippo Regius near today's Annaba/Algeria) was a Roman bishop and church teacher. Along with Jerome, Ambrose of Milan and Pope Gregory the Great, he is considered one of the four Latin Church Fathers of the patristic age of the early Church, whose consensus on dogmatic and exegetical questions was accorded canonical (binding) validity.

Critical writings against competing Christian sects and polytheistic beliefs, anti-Judaism (Tractatus adversus Judaeos), the belief in just wars of God and a sexual ethic hostile to the body had an impact until modern times. Augustine was first a rhetor in Tagaste, Carthage, Rome, and Milan. After being a Manichaean for years, he was baptized a Christian in 387 under the influence of the preaching of Bishop Ambrose of Milan; he was bishop of Hippo Regius from 395 until his death in 430. His day of commemoration in the liturgical calendar of the Roman Catholic Church is August 28, as it is in the Protestant and Anglican churches.

Augustine produced an extremely extensive body of theological, exegetical and homiletical writings, a large part of which have been preserved and have provoked an extraordinarily broad and sustained reception and impact. These writings are admittedly not free of contradictions, which he was not able to completely resolve even in the revisions (Retractationes) he presented out of this insight. Nevertheless, this did not prevent him from regarding them as a unity; he saw the Christian faith as the basis of all knowledge (crede, ut intelligas: "believe so that you may know"). The work Confessions is one of the most influential autobiographical texts in world literature. Augustine's philosophy contains elements derived from Plato, but modified in a Christian sense. These include in particular the tripartite division of reality into the world of supreme being, accessible only to the spirit, the spirit-soul of man, and the lower world of becoming, accessible to the senses. The first biography of Augustine is by Possidius of Calama, who knew him well as a student.

As one of the most influential theologians and philosophers of Christian late antiquity or patristics, he shaped the thinking of the West. In the Orthodox Church, on the other hand, he remained practically unknown; when his teachings became known in the 14th century through Greek translations also in Constantinople, they met with rejection, as far as they did not correspond to the consensus of other church fathers anyway. His theology influenced the teaching of almost all Western churches, Catholic and Protestant. The term Augustinianism characterizes its reception in religion, philosophy and historiography.

Church window with fantasy image of St. Augustine in Cologne Cathedral.

Oldest known artistic fantasy depiction of Augustine in the tradition of the author's image (Lateran Basilica, 6th century)

Contemporary historical background

The 4th century, when Augustine was born, was a troubled time for the Roman Empire. Emperor Constantine the Great had privileged Christianity and pushed back the influence of traditional god cults ("Constantine's Turn"). Constantine's sons, who succeeded him together in 337, had both to fend off the external threat of the Germanic tribes and the Neo-Persian Sassanid Empire on the frontiers and to keep the peace internally: the empire was repeatedly plagued by civil wars. At the time of Augustine's birth, Constantius II, the only one of Constantine's sons to survive the power struggles, ruled the empire. Stronger than his father and brothers, Constantius had set out to transform the Christian church into an imperial church. At the same time, there were fierce theological disputes, since Constantius adhered to the so-called "Arianism" (in its Homoean form), which was rather rejected, especially in the West. In the end, Constantius had not achieved his goal of adopting a uniform creed for the entire imperial church.

Augustine's youth coincided with the short but remarkable reign of Julian (361 to 363), who was the last emperor to be a follower of the traditional belief in the gods and who vainly strove to renew it. The succeeding emperors were all Christians. Theodosius I would eventually declare Christianity the state religion by law (380) and ban polytheistic god cults (391/92). In addition to administrative sanctions, an increasing intolerance and tendency to violent means of individual Christian groups in the form of book burnings, expropriations, destruction of temples and sacred objects became apparent on a regionally limited basis.

When the so-called migration of peoples began around 375, the Germanic tribes pushed away by the Huns pressed harder than before on the borders of the empire. At the same time, the Western Roman Empire sank deeper and deeper into civil wars, and the opposing parties summoned Germanic mercenaries, foederati. In 406/07 several warrior units crossed the Rhine frontier and invaded Gaul (see Rhine Crossing of 406). At the end of his life Augustine was to see the Vandals cross into Africa and conquer city after city. In 476 the Western Roman Empire finally fell (see also Late Antiquity). Roman Africa was to be lost to the empire until the "Reconquista" by the Eastern Roman commander Belisar in the 530s.

The period of cultural upheaval falls within the phase of climatic change described by Harper (2017) of the "Roman Transitional Period", English Roman Transitional Period (RTP) from c. AD 150 to AD 450, which followed the efflorient and prosperous period of the Optimum of the Roman period. Due to the increasing volatility of the Mediterranean climate, the general compensatory capacity of the Imperium Romanum (resilience) was successively destabilized, both in economic and administrative-political terms.

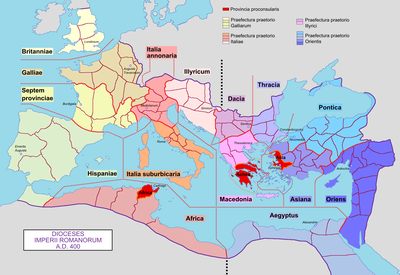

Map of the Roman Empire with its dioceses, c. 400 AD.

Theology

Trinity

His main dogmatic work is the 15 books De Trinitate ("On the Trinity"). Augustine does not deny a difference between the individual persons, whom he sees as equally eternal, equally perfect and equally omnipotent; he does not want to be a modalist, but he approaches modalism strongly. He sees the persons primarily as "relations" within the divine being.

The doctrine of the origin of the Spirit from the Father and the Son was first put forward by him. Later this statement led to the Filioque controversy.

Even after his death, his teaching made a decisive contribution to the Council of Chalcedon (451), since Pope Leo the Great, in his Tomus to the Assembly, made a key Christological statement that originated with Augustine: "two natures in one person", that is, Jesus was both God and man.

From premillenarianism to amillenarianism

Augustine is a proponent of amillenarianism and spoke out against the premillenarianism that characterized early eschatology.

First he assumed that the 5000 years from Adam to the incarnation of God according to Revelation of John (Rev) 20:1-10 were followed by the millennial kingdom. He then argued, under the influence of the allegorical interpretive tradition of the fourfold sense of Scripture, that the "millennial kingdom" did not mean an earthly kingdom, but "symbolically" denoted the period between Jesus' first and second coming. Augustine also noted that the prospect of carnal pleasures and feasting in an earthly kingdom discouraged serious observance of the commandments. Through Augustine, amillenarianism spread throughout the Western church.

Predestination

Augustine is known as a representative of predestination, in which man is predestined to eternal life by God. In his late work On the State of God (De civitate Dei), before the creation of man, he assumes two angelic states, the state of evil angels (civitas diaboli) and the state of good angels (civitas dei), some of the angels "turned away" from God "without cause" and became evil. After the creation of man, these two states were transitioned into the earthly state (civitas terrena) and the divine state (civitas coelestis), again in a dualistic orientation. After the Last Judgment, the circle closes; in the end, there are again two states: Civitas Mortalis, that is, the punishment of hell for eternity and, on the other hand, Civitas Immortalis, the eternal reign with God (heaven). The number of people who go to heaven corresponds exactly to the number of fallen angels, so that the initial state is restored:

"The other rational creature, man, who had been entirely lost through inherited and his own sins and punishments, was to supplement from his restored part what the fall of the demons had taken from the fellowship of angels."

Augustine's doctrine of double predestination - with its implicit rejection of free will to decide for God or against him by man - was not adopted by the Catholic Church as early as the 5th century, but exerted a very great influence on reformers such as Martin Luther and, above all, John Calvin and the drafting of the so-called five points of the Calvinist churches (TULIP in English). Catholics and Arminians, on the other hand, teach the necessity of the cooperation of man's free will, notwithstanding their differing views on man's justification.

The concept of the two civitates had a significant influence on the medieval two swords theory, which identified the two civitates with the ecclesiastical and secular powers, and on the two kingdoms and regiments doctrine of the Lutheran Reformation.

Doctrine of original sin and free will

Augustine had a great controversy with Pelagius, who advocated the theory of free will and accused Augustine of still being caught in the snares of Manichaeism. Pelagius was condemned in 418 in the spirit of Augustine, but found his successor in Julianus of Eclanum. It was in this even more heated controversy that Augustine developed the doctrine of original sin. In this Augustine adopted the interpretation of Rom 5:12 EU (ἐφ᾿ ᾧ πάντες ἥμαρτον) introduced by Hilarius: "In him [Adam] all have sinned," as if all had been contained in Adam (quasi in massa). This Augustinian interpretation of the pronoun ἐπί might be philologically questionable (for it actually says there, "out of" (= because of) him all sinned) and then it would also be theologically controversial. His interpretation is attributed to the fact that he had little command of biblical Greek. Unlike Pelagius, Augustine believed that original sin was physically transmitted. Augustine argued that only those who received the grace of God completely undeservedly would be able to escape this original burden and receive eternal life. For Augustine it was clear that

"God worketh in the hearts of men to incline their wills whithersoever he will: either to good according to his grace, or to evil according to their evil merits."

And he taught that of the minority who would escape hell, only a few would escape a painful purification after death.

Doctrine of Hell

Augustine believed that one must suffer endless torment in a hell. He interpreted passages like Mt 25:46 EU in such a way that the aeonian (aeternam) life as well as the aeonian punishment must be endless:

"If both are eternal, inevitably both are also either long-lasting but finite, or both are everlasting and endless."

When asked if an endless punishment for finite transgressions was not disproportionate, he replied that man deserved "eternal evil" because of original sin. Augustine denied that a judgment could have a purifying character and postulated that it alone was punitive.

In this way, Augustine, like John Chrysostom and older church teachers such as Ambrose of Milan or Jerome or Hippolytus of Rome, Origen's contemporary, strongly distanced himself from Origen's doctrine of apocatastasis. Augustine's pattern of argumentation had a great influence on Western theology that reaches to the present day.

Relationship with the Jews

Augustine directed attacks against the Jews for decades. In the sermon Against the Jews, a guide to their conversion, written toward the end of his life, he blamed the Jews of his day for the crucifixion of Jesus: "In your fathers you killed Christ." He called the Jews vicious, savage, and cruel. In the lectures on the Gospel of John from 414 to 417, he compared them to wolves, reviled them as "sinners," "murderers," "wine of the prophets degenerated into vinegar," "a bleary-eyed multitude," "stirred up filth." They were guilty of the "monstrous offense of ungodliness." Already in a Good Friday sermon of 397 he had denied them the Old Testament: "They read it as blind men and sing it as deaf men."

Augustine formulated the idea of the "servitude" of the Jews, their "servitus", which was declared "perpetual" (perpetua) by Pope Innocent III in 1205 and codified in 1234 in Gregory IX's collection of decrees, while at the same time, on the imperial side, the so-called chamber servitude of the Jews was established, based on the same ideas.

In Augustine's eyes, the Jews had a positive function for Christianity because, by not believing in the biblical prophecies about Jesus, they testified to their authenticity; "and precisely because of this testimony, which they bear to us against our will by possessing and preserving the texts, they themselves are scattered among all nations as far as the Church extends. Because they are necessary as witnesses for the Church and are intended by God, they must not be killed; they bear a mark of Cain on their foreheads. Christian rulers had to protect them, but to keep them in a subordinate position.

Pascal planned to use Augustine's argument in the chapter Proofs of Jesus Christ of his Apology of the Christian Religion, he notes in the Pensées (1670): "(...) and it (the Jewish people) must continue to exist to prove him, and it must be in misery because they crucified him".

Conflict with the Donatists

Augustine was one of the pioneers against the Donatists, represented here above all by Donatus Carthaginiensis, a rigorist group that had split off from the Catholic Church and saw itself as a church of the "pure" and "holy". In contrast, Augustine saw the Church as a community full of sinners. Together with his Metropolitan Aurelius of Carthage, they sought internal church unification. He portrays it as the field where wheat and tares grow. In addition, he claims against the Donatist demand for holiness that even the saints, as long as they live in the body, remain subject to sin, even if it is only a minor offense.

In 411 there was a religious discussion, the so-called collatio, as a result of which the influence of the Donatists decreased. As the Donatists' propensity for violence increased, he advocated putting an end to this evil through harsh punishments, strict police enforcement, and prohibition of access to courts. Augustine used as justification a phrase from a parable of Jesus, "Compel the people to come in" (Lk 14:23 LUT), which is translated in the Vulgate Latin translation as "compel them to enter" (compelle intrare) (Lk 14:23 VUL). "Toleration" in this context Augustine called only "unprofitable and void" (infructuosa et vana) and welcomed the "conversion" of many "by salutary compulsion" (terrore perculsi). The Donatists were "coerced" by the Roman state through expropriation, loss of hereditary rights, and banishments of the clergy from Africa. In 411 Honorius fined the Donatists, which was increased in 414 for high-ranking Romans, and had their bishops and priests banished from Africa. In 420 Augustine's last anti-Donatist writing Contra Gaudentium appears.

This advocacy of violence against schismatics was seen as justification for their actions when the Inquisition was introduced in the Middle Ages.

The Doctrine of Just War

After the sack of Rome in 410 by the Visigoths, then again in 455 by the Vandals under Geiserich and in 472 by Ricimer, many refugees from Rome came to the North African provinces, which at that time were considered safe from incursions by Germanic "barbarians". Since the Christianization of Rome, however, fewer and fewer Roman citizens had agreed to defend Rome, and Germanic mercenaries had to be accepted in the army. At the same time, there was still a culminating skepticism among parts of the elite against the Christianization of the empire. Even around 410, a part of the social elite (albeit a diminishing one) professed belief in the traditional gods, although this was often based on a conservative attitude and less on religious conviction. Against this reaction to the circumstances of the time, Augustine wrote his book De civitate Dei, in which he justified his theory of peace, considered inappropriate at the time, built into philosophical and theological considerations, according to which peace, not war, was the true law of nature. Pressed by further threatening circumstances of the time, which also called into question the security of North Africa (shortly after his death Hippo was also reached by the Vandals), Augustine tried besides to link this doctrine with the justification of defensive wars. He developed those theses on which the well-known doctrine of "just war" (Latin bellum iustum), further developed by Thomas Aquinas and others, was based. Following on from the approaches already existing with Cicero, he clearly emphasized that a just war, declared by a legal authority, should only have as its goal the defense of legitimate rights violated by the aggressor and should not cause greater misery than it eliminates. Augustine emphasized that war results from an unjust and inhumane attack. But he who must wage a just war should grieve over it:

"But, they say, the wise man will only fight just wars. As if, feeling humanly, he should not grieve much more over the necessity of wars! For if they were not just, he should not wage them, so there would be no wars for the wise man. Only the injustice of the opposing side compels the wise man to wage just war. ... Let him, then, who sorrowfully contemplates these great, ghastly, devastating evils, confess that they are a misery."

Augustine rejected war in several places of his work, among others with the for that time unheard-of sharp sentence that "one cannot prove that people are happy who always live in war hardships and wade in the blood of citizens or enemies, in any case in the blood of men ..." Moreover, he taught - probably for the first time in human history - that peace (and not war) was the natural law - created by God - (XIX,12,13) and the ultimate goal (XIX,14) of mankind. Everything that existed existed only in so far as peace was in it, but war was a misery.

In view of the necessity since Constantine (that is, after the end of the persecution of Christians) of also assuming state offices and Roman military service, he formulated the following compromise:

"To make war, and to enlarge the empire by subjugating nations, appears to the wicked as happiness, to the good as compulsion. But because it would be worse if the unjust ruled over the just, that too is not inappropriately called happiness."

In the context of his polemic against Manichaeism, however, Augustine himself fundamentally contradicted these thoughts:

"What, indeed, is so wrong with war anyway? That people die who will eventually die anyway, so that those who survive can find peace? A coward may whine about it, but people of faith do not [...]. No one should ever doubt the justification of a war commanded in God's name, for even that which arises from human greed cannot harm the uncorruptible God or his saints. God commands war to exorcise, crush, and subdue the pride of mortals. To endure war is a trial of the patience of the faithful to humble them and accept his fatherly rebukes. For no one possesses power over others unless he has received it from heaven. All authority is exercised only by God's command or permission. And so a man may fight righteously for order even when he serves under an unbelieving ruler. Whatever he does is either clearly not against God's ordinance, or at least not clearly against it. Even if giving an order should make the ruler guilty, the soldier who obeys him is innocent. How much more innocent must there be a man who wages a war commanded by God, who, after all, can never command anything wrong, as everyone who serves him knows?"

This work Contra Faustum Manichaeum is still not available in German translation; its contents did not have much influence on European intellectual history outside of Great Britain (and the USA). Only a short section of the work refers to the wars at the time of Moses, which according to the Bible were commanded by God himself, and which Augustine tries to defend: According to Augustine, it follows from God's omnipotence that ultimately there can be no war on earth against God's will. But if there are also just wars, war is not per se bad. But Christians may also fight for pagan or unjust rulers, because all power on earth is granted by God (neque enim habet in eos quisquam ullam potestatem, nisi cui data fuerit desuper), and even more so in every war that is waged in God's name, since God can never command anything evil (quem male aliquid iubere non posse). One should not doubt the justice of such wars (dubitare fas non est).

Defense against God's enemies was therefore justified for him even if it was just as cruel as a war waged for selfish reasons. Augustine presupposed a natural order of the "good" who would stand together against the "bad" partly as commanders, partly as obeyers; he considered it necessary to defend this order also militarily. Iusta autem bella definiri solent, quae ulciscuntur iniurias: such wars were definable as just, avenging crimes. He also declared war against heretics or schismatics like the Donatists to be just, in order to preserve the unity of the Church with the help of the state army. To be sure, the keynote of Augustine's work is the pursuit of peace, which should also define just war.

Augustine's criteria for a just war of the Christian-influenced Roman Empire were:

- He must serve and restore peace (iustus finis).

- It may only be directed against a wrong committed against the enemy - a serious violation or threat to the legal order - which continues to exist because of the enemy's conduct (causa iusta).

- A legitimate authority - God or a prince (princeps) - must order the war (legitima auctoritas). In doing so, the prince must preserve the domestic order, that is, the given structures of commanding and obeying.

- His war command must not violate God's command: The soldier must be able to see and carry it out as a service to peace.

The Church as Mediator

In his doctrine of the church (ecclesiology), Augustine emphasized the role of the church as mediator between God and man. He wrote:

"I wouldn't even trust the gospel if I wasn't moved to do so by the authority of the church."

Augustine's ecclesiology came to the conclusion that the church must have interpretive sovereignty and mediatorial character. It is excluded for him that man can become blessed and faithful through the believing reception of biblical words alone as an individual without the organization church. A standardizing authority was needed to determine which of the many possible interpretations was the correct one. Doctrines laid down in councils under the sovereignty of the church therefore have the same status as the faith tradition and the biblical text, and claim to represent the only correct view of the faith. If one wants to believe "rightly", one must believe the teachings of the church.

With this approach Jesus Christ was retained as the sole mediator between God and the individual, but the church as "salvation organization" was placed beside it as equally indispensable for the personal salvation of the individual.

Demonology

The idea of demonic forces is regularly found in ancient thought and Greek mythology, where they were first assumed to be the cause, in the sense of supernatural beings, of all natural phenomena. In his writing "De Civitate Dei contra Paganos" Augustine dealt in detail with the doctrine of demons of Apuleius Madaurensis and his writing "On the God of Socrates" and criticized it from his perspective.

Although Augustine seeks distance to the "ancient demonology" and contradicted for instance the demon doctrine of a Middle Platonic philosopher Apuleius of Madaura and of the Neoplatonist Porphyrios, there are nevertheless common starting points in Augustine's thinking and thus also various similarities with the late antique conception of demons. Thus Augustine distinguishes, for instance, between "good" and "evil angels", of which the former live close to God in the higher spheres, but the latter are distant from God and separated from the good angels. The foundations of "Christian demonology" were developed by Augustine, he was influenced by dualistic Manichaeism, his doctrine of the two realms was based on a dualism, namely the civitas Dei and the civitas Diaboli.

In evangelium Ioannis , 1050-1100 ca., Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence

Search within the encyclopedia