Oregon Trail

![]()

This article is about the 19th century settler's route across the Rocky Mountains. The computer game of this name can be found under The Oregon Trail.

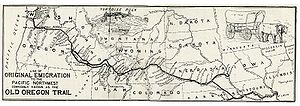

The Oregon Trail was a 2200-mile (3500 km) route used around the mid-19th century by settlers from then-settled parts of the eastern and central United States to travel across the Rocky Mountains to the western United States. The journey was mostly made in covered wagons and took them through steppes, deserts and mountains to settle new regions in the Pacific Northwest. Large portions of the route were also used for treks to other parts of the West.

In the early 19th century, the British, as owners of what would later become Canada, and the United States had agreed to jointly settle the areas west of the Rocky Mountains, but a few years after the first American pioneers arrived, the two states decided in 1846 in the Oregon Compromise to divide the area along the 49th parallel. Settlement of the southern, U.S. half thus really began, and the Oregon Trail grew in importance. Beginning in 1847, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) also moved across the mountains on the Trail, but then branched off on the Mormon Trail to the Great Salt Lake. When the California Gold Rush broke out in 1849, the Oregon Trail evolved into the California Trail, which was identical to the known route until it crossed the Rocky Mountains and only then went more southerly. The days of the treks and the Oregon Trail came to an abrupt end when the first transcontinental railroad connection was completed in 1869. The trail was added to the National Trails System in 1978.

The Oregon Trail was traveled for the most part from east to west. The journey in the opposite direction was incomparably more dangerous, because only in small groups could be traveled and since the Californian gold rush gold was suspected with them. According to one estimate, about 1200 people traveled west to east in 1853 and about 600 to 1000 in 1855. In the same years, more than 35,000 people (1853) and almost 7,000 people (1855) moved from east to west.

History

Thanks to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804/1806, there were first maps of parts of the route. However, the route used by the expedition over Lolo Pass in the Rocky Mountains was too steep for settlers with baggage and covered wagons. In 1810, John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company initiated an expedition to find a supply route for the Fort Astoria fur trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River. Although the expedition and base were a failure, the Astorians returning in 1811 found a far better route through the Rocky Mountains: the South Pass. Their discovery was not mentioned in the official report, however, because the American Fur Company did not operate in the central Rocky Mountains and did not want to announce the pass to its competitors.

Some expedition reports, for example those of Lieutenant Zebulon Pike (1806) and Major Steven Long (1819), described the Great Plains as unsuitable for settlement and called the area "the great American desert." The Great Plains were considered an uninhabitable desert in part until nearly 1880. At the same time, early missionaries reported euphorically from Oregon beginning in 1818. Missionaries, politicians, and early settlers and businessmen in the West, such as Johann August Sutter and John Marsh promoted the West as very fertile and climatically pleasant. They even described travel to the West as a health-giving cure.

Early settler treks

In February 1824, Crow and Cheyenne Indians showed the South Pass to a trapper party from the Ashley & Henry fur trading company (later the Rocky Mountain Fur Company) led by Jedediah Smith. These immediately recognized the importance and the trail was used regularly from then on by fur hunters and traders. They were joined at times by Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries who traveled across the Rockies to Oregon. In the 1830s, news spread through newspapers that fur trader William Sublette had successfully traveled by wagon to a rendezvous at South Pass and back. Until then, the Rocky Mountains were considered an impassable obstacle for wagons. In 1840, Joel Walker and his family became the first settlers to accompany the fur trade caravan west. The realization that the overland route to Oregon was passable received further impetus from a book by missionary Samuel Parker. In it, Parker described how he made the journey as an aging man in 1835. In 1841, the first group of settlers traveled to Oregon unaccompanied by experienced Mountain Men, with them were Jesuit missionaries led by Pierre-Jean De Smet. Some settlers advanced as far as Fort Vancouver in present-day Washington. Not all emigrants reached their destination. For example, in 1841 about ten percent of the travelers turned back.

On May 16, 1842, the first organized wagon train of 100 started from Elm Grove. The following year 900 settlers reached Oregon, 800 of them settling in the Willamette Valley. The settlers formed a provisional government. This brought the U.S. into conflict with the British, who had previously ruled Oregon through the Hudson's Bay Company. Despite the hostilities, John McLoughlin of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver generously supported the new settlers from 1842 to 1845. The British press ridiculed the intention of American citizens to reach Oregon by way of the Rocky Mountains, or doubted the seriousness of the emigration attempts. The British press maintained this attitude to some extent until about 1844, when emigration was long in progress. In 1846 the Oregon Compromise settled the boundary between the British and the United States in the West. On its basis the Oregon Territory was created two years later on the side of the USA. With the border treaty, the British press lost interest in the emigration of American settlers.

The American press, under the influence of Horace Greeley, was also initially critical of emigration to the West and did not see the need, since there was sufficient fertile land available in the East. Emigrants were criticized for putting their families in unnecessary danger. By the mid-1840s, the mood tilted, and skepticism gave way to euphoria about extending the territory of the United States to the west coast of the continent. Henceforth, emigrants were lauded as heroes and the dangers of the journey were downplayed. The explorer and politician John C. Frémont promoted the South Pass as an easier crossing over the Rockies. U.S. President James K. Polk proposed in 1845 to reward successful pioneers who reached Oregon with a free piece of land. His push failed, however.

Soon enterprising individuals were offering their services along the Oregon Trail. In 1843, the first commercially operated ferry was launched on the Kansas River. Because of the high price, however, most emigrants built their own ferries. In Oregon and California, many early settlers helped newcomers, provided medical care, offered shelter, met them with provisions, and patrolled for hostile Indians. Mission stations were also important to immigrants who arrived late in the year and were desperate for a place to spend the winter. In California, John Sutter, with his Fort Sutter, particularly excelled in generously assisting immigrants in need.

In the winter of 1846, one of the greatest disasters in the history of the Oregon Trail occurred: About 90 emigrants under the leadership of George Donner were surprised by early snowfall on their way to California at Donner Pass. About half of the Donner party died and many of the rest survived only thanks to cannibalism. This event was mostly kept quiet in the press, but from this point on the euphoric-romantic reporting gradually changed to a more realistic one and newspapers published useful information about the route as well as letters from settlers in Oregon.

Many hundreds of thousands of emigrants to Oregon and California followed, especially after the discovery of gold in California in 1848. During this time, cholera spread across the prairies. The increasing number of emigrants put more and more pressure on the Indian tribes in the West and tensions between emigrants and Indians increased. Presumably introduced measles, which caused many deaths among the Cayuse and Umatilla Indians, turned them against the white settlers. In 1847, Cayuse and Umatilla Indians perpetrated the Whitman Massacre of missionary Marcus Whitman, his family, and 15 other settlers. The ensuing Cayuse War necessitated military involvement in the Pacific Northwest. The war ended in 1855 with the defeat of the Indian tribes involved and their relocation to Indian reservations.

Expansion and improvement of the trail

The route was steadily improved, shortened and the infrastructure along the route expanded both by the government and private initiative. In 1845, Colonel Stephen W. Kearny had led a U.S. Army troop to South Pass and back east for the first time. The following year, the U.S. Parliament gave money to establish Army posts along the Oregon Trail. Stephen W. Kearny had a first station built on the west bank of the Missouri River, Fort Kearny. Construction of the fort chain was delayed due to the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, and Fort Kearny was also temporarily abandoned.

In 1849, the approximately 600 men of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry Regiment rode the entire length of the Oregon Trail, establishing military posts along the way. After Fort Kearny, Fort Laramie and Fort Hall were the next military posts, with the army buying both forts from private traders and converting them into military bases. Fort Hall was abandoned again the next spring due to difficulty in resupply. In May 1850, Camp Drum was established. During the 1850s, the 3rd U.S. Cavalry Regiment built more army posts in areas with increased potential for conflict with Indians. For Oregon Trail travelers, the military posts provided not only shelter but also opportunities to obtain provisions and spare parts. Often, desperate emigrants even received basic necessities free of charge at army posts. In the 1850s, up to 90 percent of U.S. Army troops were stationed at the 79 army posts west of the Mississippi.

The U.S. government also tried to pacify the trail through negotiations with Indian tribes. In 1848, it paid $2,000 for 600 mi². In 1851, it invited various tribes to a meeting at Fort Laramie. Over 10,000 Indians attended. At this meeting, the Treaty of Fort Laramie defined the boundaries and gave the US permission to build forts and roads. In exchange, the Indians were promised $50,000 worth of trade goods annually for 50 years. However, not all groups of the tribes involved took part in the meeting; they did not feel bound by the agreements.

Around 1850, more and more settlers settled along the way and offered their services. Privately operated ferries, bridges, smithies, trading posts and the like were established. Initially, the trading posts often consisted only of simple tents. As early as 1843, Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez had established Fort Bridger, a private trading post on the Oregon Trail southwest of South Pass. In many cases, workshops settled immediately adjacent to ferry operations. Travelers especially made frequent use of the services of blacksmiths. In the area west of South Pass, the Mormons especially participated in the business activities. In 1849, it cost five dollars to pass a wagon on one of their ferries, and the revenue from this ferry was an estimated $6500 to $10,000 for the entire season. To compete with the ferries, entrepreneurs increasingly built bridges, but these required large initial investments. For example, in 1853, a new bridge was built over the North Platte River at a cost of $14,000 to $16,000. In its first year of operation, however, the bridge brought in $40,000. The difference in prices in the East and West stimulated the business of merchants. Cattle purchased in Missouri, for example, could be sold in California at several times the purchase price. It was worthwhile for cattle traders to drive sheep, steers, cows, and horses westward, even if they faced a loss of 10 to 20 percent along the way. This activity peaked between 1852 and 1854, and for 1853 the number of sheep and cattle driven west overland is estimated at 300,000.

In August 1850, a state monthly letter post service began between Independence and Salt Lake City, and in 1851 an intermediate station was established at Fort Laramie. In the same year, another letter post service was established between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. In many cases the letters arrived late and in some cases not at all. In 1858, the delivery interval between Independence and Salt Lake City was increased to one week. In 1860, private competition emerged in the form of the Pony Express. Just one year later, letter couriers lost importance due to the new telegraph network.

The California Gold Rush changed the composition of emigrant groups. Previously, emigrant families were the main group on the move; with the gold rush, it was primarily men. During the California Gold Rush, the first newspapers in the West sprang up in California and Oregon, demanding increasingly insistent support and military protection of the Oregon Trail from the U.S. government. The early 1850s were climatically difficult, so many emigrants had to leave all possessions behind along the way and reached their destination only with extreme effort on foot. Many of the emigrants headed for California changed their route to Oregon. The superintendents of Washington and Oregon were interested in peace with the Indians. For example, in 1856, groups of the Shoshone received gifts worth $4,500.

In 1854, a cow belonging to an Oregon Trail traveler that strayed to a Lakota Indian camp and was killed there led to the Grattan Massacre. The skirmish was the first armed confrontation between the Lakota and the US Army.

In 1857, Mormon settlers left the Carson River Valley and moved northeast, establishing Salt Lake City and nearly 400 other settlements.

In 1860, Frederick Lander had large reservoirs built at Rabbit Hole Springs and Antelope Springs.

The end of use

Around 1850, ideas for alternative forms of travel emerged, such as travel by balloon, stagecoach or wagons supported by wind sails. Businessmen implemented the idea of a passenger train pulled by draught animals from 1849 onwards. Some of these trains reached much higher speeds. In 1860, one such train made the trip from St. Joseph to Salt Lake City in 19 days. However, traveling by train cost several hundred dollars more than traveling by covered wagon. In addition, passengers could only carry a limited weight of luggage.

Toward the middle of the 1850s, the first calls for a railroad across the American continent emerged. In the East, newspapers in the 1850s reported on the Oregon Trail in a noticeably more objective and less romanticizing or dramatizing way than before. Emigrants were therefore usually better prepared for the journey.

The route was still in use during the American Civil War. The trail became less important when the transcontinental railroad opened in 1869. Its route ran further south.

Demolition of a camp at sunrise. Painting by Alfred Jacob Miller

Oregon Trail Ruts in Wyoming, a National Historic Landmark where you can still see the tracks of horses and wagon wheels in the sandstone

Routing

Great Plains

Various towns in the east competed with campaigns to be the leading town for outfitting and starting westward travel. In the early years of the Oregon Trail Independence occupied a very important position, which it gradually lost to St. Joseph and Kanesville with the gold rush. Kanesville especially served the Mormons as a starting point for their emigration to Utah. St. Joseph, Kansas City, and Kanesville were all located on the Missouri River. The outfitting of settler treks was of great economic importance. In 1849, for example, prospectors spent $150,000 in Independence.

The route from Independence led northwest to the Little Blue River. During the times of active use of the Oregon Trail, the foundation was laid on the way for several towns such as Lawrence (Kansas) and Topeka. West of Marysville (Kansas) the route merged with that from St. Joseph. The settlers followed the Little Blue River roughly to south of present Hastings (Nebraska), where they traveled further northwest to the Platte River. In 1848, the military post of Fort Kearny was established there on the Platte River.

The Oregon Trail now essentially ran along the Platte River through the Great Plains, between Fort McPherson and California Hill the South Platte River, and then roughly to present-day Casper (Wyoming) the North Platte River. Settlers oriented themselves to landmarks such as Chimney Rock, Register Cliff, Laramie Peak, Ayres Natural Bridge, and Independence Rock. At some landmarks, such as Register Cliff, many settlers left their name and a year as a sign and message for those who followed. The terrain rises continuously at a barely noticeable rate on this section of the trail, from the confluence of the North Platte River with the South Platt River at 850 meters to Casper at 1550 meters. Traces of the wagons and draft animals still remain in an eroded sandstone rib on this section at Oregon Trail Ruts for about 800 meters. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

Rocky Mountains and Blue Mountains

After Casper, the settlers moved away from the North Platte River and continued west to the Sweetwater River. With it they reached the Rocky Mountains, which they crossed over the South Pass, situated at an altitude of 2265 meters. The route continued to Fort Bridger, north of Bear Lake via Soda Springs to Fort Hall, where they reached the Snake River at an elevation of about 1350m.

Beginning in 1840, the U.S. government had exploratory expeditions conducted in the Rocky Mountain area, which led to major improvements to the route, especially beginning in 1850. In 1857, the U.S. Congress appropriated $300,000 for a road between Kearny and Honey Lake in California. Under the direction of Frederick Lander, the construction of the road saved five days of travel in time. Overall, improvements by the U.S. government shortened travel from over 130 days to under 70 days in some cases. In 1858/59, James H. Simpson constructed a new route between Camp Floyd and Fort Bridger that saved 288 miles.

Along the Snake River, the traditional route continued through what is now Twin Falls to Glenns Ferry. There, some settlers continued to follow the Snake River, others moved on a route further north via present-day Boise to Fort Boise, where they again encountered and crossed the Snake River. Beginning in 1862, the route shifted. In that year, Shoshone and Bannock Indians blocked the main Snake River route as they resisted whites encroaching on their land. To evade the Indians, the largest settler train ever on the Oregon Trail, with 338 wagons and 1095 people, was led by Tim Goodale via a northern route, known from then on as the Goodale Cutoff and favored in subsequent years as well. This route led along the northern edge of the Snake River Plain and thus avoided the extensive and unexplored lava fields of today's Craters of the Moon National Monument until it met the river again at Bliss and followed it to Boise.

After crossing the Snake River, their route merged with one south of the river, and the settlers could already see the Blue Mountains ahead. The further course of the route to Pendleton, which emerged in the middle of the Oregon Trail phase, roughly coincides with today's Interstate 84. Unlike the latter, they did not move directly to the Columbia River, but traveled further north and did not meet the Columbia until before The Dalles.

Immigrants then had to decide whether to float down the Columbia to Fort Vancouver or take a very steep route, the Barlow Road, to the Willamette Valley. The Barlow road was established as a toll road in 1846. The toll was five dollars for each person and ten cents for each head of cattle. It was named for Samuel K. Barlow, who discovered the route from Tygh Valley in Northern Oregon to Oregon City in 1845. Most settlers continued on to the Willamette Valley. The only alternative was a strenuous and dangerous route across the Columbia River.

Barlow Road was designated a Historic District in 1992. It has been part of the Mt. Hood Scenic Byway since 2005. Today's surface roads run mostly on or beside the trail, such as U.S. Highway 26.

Route improvements reduced travel time from an average of 166 days in 1841-1849 to 129 in 1850-1860.

Oregon and California competed as destinations in much the same way as the starting points. One argument for California until 1846 was the threat of war with England in Oregon. In Oregon's favor was the possibility of traveling by water from The Dalles to Fort Vancouver, Portland, or Oregon City thanks to the Columbia River.

In 1845, a delegation from California traveled to Fort Hall to persuade the Oregon Trail settlers to settle in California. They offered to provide guides for the emigrants and to meet them with provisions. These measures proved successful, so they were repeated the following year. However, Oregon now also sent a delegation to Fort Hall and most of the settlers chose to continue on to Oregon. Both parties were also anxious to improve the route to them.

The end of the Oregon Trail was typically Oregon City. As an alternative to the waterway, Samuel Barlow established the Barlow Road in 1846. The next year, a route from the south to Salem, the Applegate Trail, was created as an extension of the California Trail.

Stone erected by Ezra Meeker in 1906 on South Pass

South Pass in Wyoming, the most comfortable passage over the Rocky Mountains

Oregon Trail

Scotts Bluff in Nebraska

Questions and Answers

Q: Why did people travel on the Oregon Trail in wagons?

A: People traveled on the Oregon Trail in wagons in order to settle new parts of the United States of America during the 19th century.

Q: Where did the Oregon Trail start and end?

A: The Oregon Trail started in Missouri near the area where Kansas City, Missouri is today and ended in the Willamette Valley in Oregon.

Q: How long was the Oregon Trail?

A: The Trail was about 2,170 miles (3,500 km) long.

Q: Why did people go to Oregon?

A: People went to Oregon for many reasons. Some people wanted land. Some thought Oregon would be a better place to live. Most of them went because they wanted a new life.

Q: When was the Oregon Trail first traveled?

A: The Oregon Trail was first traveled around 1841.

Q: When did fewer people begin to travel west in wagons and why?

A: Fewer people began to travel west in wagons once a railroad was built across the United States in 1869, allowing people to take trains to the western United States.

Q: How many people had crossed the Oregon Trail in wagons by the time the railroad was built?

A: By the time the railroad was built in 1869, about 400,000 people had crossed the Oregon Trail in wagons.

Search within the encyclopedia