Ophthalmology

Ophthalmology (also ophthalmic medicine, also ophthalmiatry; from the ancient Greek ὀφθαλμός ophthalmos, German 'Auge', also 'Sehen') is the study of the structure, function, diseases and dysfunctions of the visual organ, its appendages and the sense of sight and their medical treatment. It is one of the oldest medical subdisciplines. Ophthalmologist (synonym: ophthalmologist) is the professional title (first documented as ougenarzt in 1401) of the specialist who deals with ophthalmology. In the past, ophthalmologists were also referred to as oculists.

The anatomical boundaries of ophthalmology are formed by the eyelid and facial skin at the front and the bones of the orbit at the back. With the examination possibilities of the visual pathway and the visual cortex, they extend beyond this to the back of the skull. There are close relations to otorhinolaryngology, dermatology and neurology. Because of the frequent involvement of the eye in general diseases and the possibility of performing microscopic examinations on living tissue, ophthalmological findings are often used to establish diagnoses for internal medicine and neurology (neuroophthalmology).

Modern ophthalmological examination methods require extensive and expensive technical and instrumental equipment. The most important examination device is the slit lamp, a powerful stereo microscope equipped with special control and illumination mechanics.

Ophthalmology is one of the surgical sub-disciplines, although it has many effective and sophisticated drugs and tools at its disposal. With cataract surgery, ophthalmology is the most frequently performed and, in total, the most costly medical operation in the world.

Slit lamp examination, 2008

History

Ancient Oriental, especially Babylonian and Mesopotamian ophthalmology is already attested in Babylonian cuneiform texts. In the Tablets of the Law of Hammurapi, over 3600 years ago, regulations for eye operations were issued: The Babylonian or Assyrian physician was to receive a reward of 10 shekels for a successful operation, whereas in case of failure (due to ophthalmological malpractice) both hands were to be chopped off.

From the Egyptian medicine of the time from 2500 to 500 BC, when there were already specialist doctors for eye treatments, some papyri, such as the Papyrus Ebers or the Papyrus Carlsberg, are known with ophthalmological therapy instructions. Also around 280 B.C. until about 200 A.D., in Alexandria, the medical centre of the Upper Egyptian, Greek, Indian and Near Eastern world at that time, there were collections of prescriptions for the treatment of eye diseases, which were common in Egypt. Around 500 B.C., the Indian physician Sushruta also wrote ophthalmological texts, some of whose content is found in the 16th-century ophthalmological work Bhavamisra (Bhāvamiśra) by Bhavaprakasa (Bhāvaprakāśa), which summarizes ancient learning. Ancient Indian medicine distinguished 78 eye diseases whose origin depended on certain humors (doshas).

The biblical book of Tobit mentions the treatment of a macula caused by fish bile after corneal burns caused by warm swallow droppings.

Although ophthalmology is not described in detail in the Corpus Hippocraticum of ancient Greece (5th century B.C. to 1st century A.D.), which is mainly attributed to Hippocrates (c. 460-370) and which forms the basis of scientific medicine, there are some references to ophthalmological therapies. Writings on eye anatomy (based on animal eye dissections) were written by Alkmaion of Kroton (c. 500 BC), who was the first to describe the optic nerve, and Herophilos of Chalcedon (c. 300 BC). Knowledge of the eye anatomy of the Alexandrian Greeks has been preserved above all in Galenos (c. 129-201), who wrote a "Diagnostics of Eye Diseases" at an early age. His ocular anatomical description of the retractor bulbi shows that his descriptions are based on animal anatomy.

The first optical correction reported by Pliny the Elder is that the Emperor Nero held a cut emerald in front of his eye in 66 AD because of his short-sightedness as a spectator at a fencing competition, although it remains unclear whether the emerald served more as an ornament or actually as an optical aid and whether it was concave or convex in cut. There is evidence of the treatment of eye diseases or injuries in ancient Rome. Antyllos, an important Greek surgeon at the time, is said to have operated on cataracts in Rome around 140 AD, as well as performing surgical procedures to treat lacrimal fistulas and rolled eyelids. Around 40 AD, Aulus Cornelius Celsus described the typical colouring of the sclera of the eye in jaundice.

The ophthalmologists in Gaul were very much influenced by Greek medicine. A practice of prescribing by Gallic specialists not found among Greek and Roman physicians were, especially from the 2nd to the 4th century, platelets used as stamps, which contained the name of the ophthalmologist, the names of the prescribed eye drops and the expected healing effect.

In the 9th century, Hunain ibn Ishāq (a Christian Arab physician also known as Johannitius) produced a ten-volume work on ophthalmology, which is the oldest Arabic textbook on ophthalmology, was edited in Latin by Constantine of Africa in Salerno, and became the basis of ophthalmology taught at Western universities as Liber de oculis Constantini Africani. Also in the 9th century, Yuhanna ibn Masawaih is said to have written his ophthalmological treatise Kitāb Daġal al-ʿain ("The Defectiveness of the Eye").

Important medieval authors of other Arabic ophthalmological texts were Rhazes (9th/10th century), who mentioned pupillary reaction to light incidence, and Jesu Haly (11th century) as the author of a three-part textbook of ophthalmology, as well as Avicenna in the 11th century. Century and Averroes, who recognized in the 12th century that light is absorbed by the retina, and the ophthalmologist and medical biographer Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa, who was active in the 13th century.

In the 12th century, a widely travelled Jewish author and famous star engraver named Benevenutus Grapheus, who was active in Italy and Occitania (Languedoc), possibly from Jerusalem, also wrote the ophthalmological text Practica oculorum, which appeared in several languages, first in Provençal dialect. Around 1250, the likewise widespread Liber de oculo by Petrus Hispanus, later Pope John XXI, was written.

In the Middle Ages, ophthalmology was mostly practiced by wound physicians and since the Middle Ages eye operations were performed by specialized craft surgeons (by so-called cataract surgeons or oculists), the most famous of whom was Doctor Eisenbarth. By means of a special knife, the cloudy lens of the eye ("cataract") was pushed into the eye. The word "ophthalmologist" is first documented in 1401 (as ougenarzt).

An important German-language work on ophthalmology is the "Pommersfeldener Augenbüchlein" (buchlin von den wetagen der augen und buße dar mede), which was written in Silesia around 1400 (one of two or three authors is named as Master Johannes), cites therein, among others, the authors Arnold von Villanova (Libellus regiminis de confortatione visus) and Jesus Haly (Kitāb Taḍkirat al-kaḥḥalīn of "iesu uz Gelrelant geborn"), and mentions the contemporary traveling ophthalmologist Pankraz Sommer, who traveled from Hirschberg to Silesia and Bohemia, and "etliche jüdische Augenärztinnen." Connected with the Augenbüchlein in a collective manuscript (of the Pommersfeld castle library) is also the announcement of the establishment of the travelling oculist and ophthalmologist Lorenz Thüring (or Doring) from Vienna, who served as personal physician to Emperor Sigismund and King Albrecht II, written around 1445.

After the Pommersfeldener Augenbüchlein from the first third of the 15th century and an anonymous booklet from 1538, the first more comprehensive German-language textbooks on ophthalmology include an appendix to the Practica copiosa by the surgeon Caspar Stromayr published in 1559 and the Lehr- und Handbuch Augendienst by Georg Bartisch published in 1583. Bartisch was also the first to surgically perform an enucleation of the eyeball. Ophthalmology initially belonged to surgery and did not emerge as an independent specialty until the 18th century, and especially the 19th century, and the traveling oculists were eventually ousted from the medical profession from the 18th to the 19th century. Until the 18th century, the anatomy and functioning of the eye was obscure. Beginning in the 19th century, the advent of the microscope revealed details and made them systematically useful for therapy. In 1800 Carl Gustav Himly coined the name ophthalmology, in the same year Thomas Young described astigmatism.

The traditional cataract stitch for the treatment of cataracts was replaced in the middle of the 18th century (Jacques Daviel) by the removal of the clouded lens from the eye.

The first private eye clinic in Germany was established in Dresden in 1782 by the Saxon court oculist Giovanni Virgilio Casaamata (1741-1807). Further clinics were opened in Erfurt and Budapest in the early 19th century. After Joseph Barth, the first full professor of ophthalmology, Georg Joseph Beer (1763-1821) also held a chair of ophthalmology. He had become full professor of ophthalmology in Vienna in 1818, the year in which attendance of ophthalmological lectures also became compulsory for students at the University of Vienna. Prior to this, he had opened the first university clinic for eye patients in Vienna in 1813, where ophthalmology had already been separated from surgery in 1812.

The first lectures on ophthalmology in Great Britain were given by the surgeon and ophthalmologist George James Guthrie (1785-1856) at the Royal Westminister Ophthalmic Hospital, which he founded in 1816. After French, German and Italian textbooks were still the most authoritative in ophthalmology at the beginning of the 18th century, British textbooks such as on the pathology of the eyes by James Wardrop (1782-1869) or the first complete textbook of ophthalmology by Benjamin Travers (1783-1858) gained importance in the 19th century. The first American textbook of ophthalmology was published by E. Frick in Baltimore. One of the first important scientific ophthalmologists in the United States was Jakob Knapp (1832-1911) in New York.

Groundbreaking inventions in the field of diagnostics were those of the ophthalmoscope by Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894) in 1851 and the perimeter by Richard Förster (1825-1902). The physiologist Frans Donders was also one of the pioneers of ophthalmology at this time. Major advances were the surgical treatment of glaucoma by Albrecht von Graefe (1828-1870), who is considered the "father of ophthalmology", the introduction of anesthesia into ophthalmology by Henry W. Williams (Boston, 1850), and the first successful transplantation of the cornea (keratoplasty) in 1905 by Eduard Zirm (1863-1944). The Copenhagen physician and lecturer in microscopic anatomy Adolf Hannover (1814-1894), who was awarded the Montyon Prize of the Paris Academy in 1856 and 1878, also contributed to the knowledge of the exact structure of the eye, its functions and its diseases in the mid-19th century. In 1928, the then fundamental monograph Syphilis and the Eye by Josef Igersheimer (1879-1965), professor of ophthalmology in Frankfurt, Istanbul (1933-1939) and Boston, was already published in its second edition (The important 1937 Ophthalmological Congress in Vienna was hosted by Igersheimer). A pioneer in the field of corneoplasty was the Russian researcher Vladimir Petrovich Filatov.

A decisive advance for ophthalmology was the discovery in 1884 of the anaesthetic effect of cocaine on the conjunctiva and cornea by Koller, who used a two-percent solution for cocaine anaesthesia.

In 1961, the Polish ophthalmologist T. Krawitz developed the cryoextraction technique for cataract surgery, in which the eye lens hardened by cold could be removed without bursting (intracapsular technique, in which the lens capsule is also removed), which was then replaced by the extracapsular extraction. This technique, unlike the intracapsular one, allowed the preservation of the lens capsule for the placement of the intraocular lens. The lens nucleus was initially delivered through a wide incision, and since the 1970s has been disrupted by ultrasound (phacoemulsification). In the 1990s, this became the standard procedure. Later, the femtosecond laser-assisted surgical technique was added.

Further milestones in the development of ophthalmology since the middle of the 20th century are

- the development of the intraocular lens, which made cataract glasses obsolete

- the discovery of sunlight coagulation in 1949 by Gerhard Meyer-Schwickerath, the forerunner of laser coagulation as a way of treating diabetic retinopathy, which has reduced the blindness rate among patients with diabetes mellitus to less than 1/10 of previous levels

- the development of vitrectomy (removal of the vitreous body), with which numerous diseases previously leading to blindness can now be treated.

- the introduction of occlusion (temporary and, if necessary, alternating covering of one eye) for the successful treatment or prophylaxis of amblyopia (early-acquired, functional amblyopia), especially in strabismus.

- the development and specification of eye muscle operations for the treatment of strabismus, nystagmus and ocularly caused head restraints, in particular by Curt Cüppers.

- the development of anti-VEGF factors (e.g. Ranibizumab), which are injected into the vitreous body and which can significantly slow down the progression of diseases leading to blindness, such as exudative (wet) age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy, or cause regression in diabetic macular edema.

In recent times, electronically controlled laser systems have been increasingly used, for example in refractive surgery or in the diagnosis of the retina and the optic nerve (optical coherence tomography).

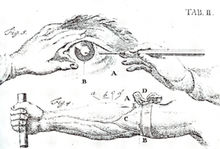

Schematic representation of the "Starstich" (1764)

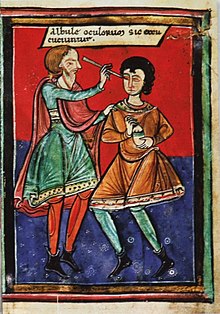

Eye surgery (cataract) in the Middle Ages; the text says: "The whitish opacities of the eyes are thus removed."

Major eye diseases and dysfunctions

- of the anterior and middle sections of the eye: (eyelids, lacrimal apparatus with lacrimal glands and draining lacrimal ducts, conjunctiva and "tear film", sclera, cornea, iris, crystalline lens and vitreous body):

- Eyelids, lacrimal gland and lacrimal ducts

- Dermatochalasis (sagging of the eyelid skin)

- Ectropion (outward rotation of the eyelid edge)

- Entropion (inward rotation of the eyelid edge)

- Inflammations (blepharitis, dacryoadenitis, dacryocystitis, stye, erysipelas, lid abscess)

- Lagophthalmos: incomplete lid closure

- Marcus Gunn syndrome: coinnervation disorder of oculomotor nerve and mandibular nerve

- Ptosis (drooping of the eyelids)

- Lacrimal duct obstruction (congenital or acquired)

- Tumours (basal cell carcinoma, chalazion, squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma of the corneal gland, hidrocystoma, melanoma, Kaposi's sarcoma)

- Injuries (with and without eyelid edge involvement)

- Xerophthalmia (drying of the ocular surface due to lack of tear production)

- conjunctiva (conjunctiva) and "tear film":

- Degenerations (Pinguecula, Pterygium)

- Hemorrhages (Hyposphagma)

- Inflammations (conjunctivitis)

- keratoconjunctivitis epidemica

- Xerophthalmia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (see also Sjögren's syndrome)

- rare tumours (lymphoma, melanoma)

- Injuries (conjunctival tear)

- Sclera

- inflammation (scleritis), usually in the context of an autoimmune disease

- Injuries (accident, surgical)

- Cornea:

- Degenerations (Arcus senilis, Terrien's degeneration, ligamentous degeneration)

- Dystrophies (epithelial: Map-Dot fingerprint dystrophy, stromal: e.g. lattice corneal dystrophy, endothelial: Fuchs endothelial dystrophy)

- Inflammation (keratitis), ulcer (corneal ulcer)

- Keratitis photoelectrica = blinding: damage to the corneal surface (epithelium) by ultraviolet radiation, typically after welding without protective goggles, corresponds pathophysiologically to sunburn

- Snow blindness in snow-covered regions when exposed to strong sunlight for a long time

- Keratoconus, keratoglobus, cone- or spherical deformation mostly of the central cornea, genetically caused

- Burns

- Injuries caused by foreign bodies (iron filings, small stones, glass, plant thorns, etc.), epithelial defects (erosio corneae)

- Iris

- Defective coloboma, traumatic or congenital

- Inflammation (iritis), usually endogenous in the context of an autoimmune disease, e.g. Bekhterev's disease

- Disorders of the pupil and pupillomotor function, miosis (narrow), mydriasis (wide), rounded pupil (traumatic, due to synechiae)

- Eye Lens:

- Aphakia: the absence of the lens of the eye (often after surgery, rarely congenital)

- Cataract: clouding of the eye lens, cataract, mostly degenerative, rarely traumatic

- Lens luxation: tearing off of the lens from its suspension

- Vitreous:

- Vitreous detachment: common, physiological (not pathological) phenomenon, sometimes leading to mouches volantes and rarely to retinal detachment.

- Mouches volantes: Perception of vitreous opacities

- Synchisis scintillans: rare form of vitreous opacities

- of the posterior segments of the eye: Retina, Choroid and Optic Nerve.

- Retina:

- Arterial and venous vascular occlusion of the retina (central retinal artery occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion and branch retinal vein occlusion)

- diabetic retinopathy in the context of diabetes mellitus

- Inflammations (retinitis) such as toxoplasmosis retinitis

- hypertensive retinopathy in the context of arterialhypertension

- Macular degeneration, e.g. age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- Retinal detachment as a result of fluid ingress between the layer of light receptors and the pigment epithelium

- Retinoblastoma

- Retinopathia centralis serosa (Chorioretinopathia centralis serosa)

- Retinitis pigmentosa (= Retinopathia pigmentosa)

- Choroid

- uveal melanoma

- Inflammation (choroiditis), e.g. due to herpes viruses, autoimmune disease

- Optic nerve:

- Inflammation of the optic nerves, e.g. in multiple sclerosis

- Glaucoma: damage to the optic nerve caused by the intraocular pressure.

- Ischemic optic neuropathies e.g. anterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- Optic atrophies due to various causes, e.g. after neuritis nervi optici, as a result of a congestion papilla, toxic, hereditary (e.g. Leber's optic atrophy)

- of the remaining structures of the eye socket (orbit)

- Orbital floor fracture: fracture of the bony floor of the orbit, e.g. after blunt injury: squash ball, champagne cork, fist blow

- Orbitaphlegmone: inflammation of the orbit usually caused by bacteria, typically streptococci

- the position and mobility of the eyes:

- Abducens palsy, trochlear palsy, oculomotor palsy: Eye muscle paralysis

- Brown syndrome, orbital floor fracture: mechanical motility disorders

- Duane syndrome: congenital abducens paresis with coinnervation disorder of oculomotor nerve and abducens nerve

- One and a half syndrome: combination of pre- and supranuclear palsies

- endocrine orbitopathy, orbital apex syndrome, fissura-orbitalis-superior syndrome, myasthenia gravis: inflammation-related motility disorders

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia: prenuclear palsy

- Convergence excess, convergence spasm, convergence insufficiency: convergence disorders of different causes

- Nystagmus: uncontrolled eye tremor

- Obliquus superior myokymia: microtremor of the obliquus superior muscle, V. a. a neurovascular compression syndrome

- Oculomotor apraxia: central disturbance of fixation perception

- Strabismus: latent or manifest malposition of one or both eyes (strabismus)

- supranuclear gaze palsies including Parinaud syndrome

- the sensory system of binocular vision

- Diplopia and confusion: double image perception

- Suppression: suppression of the visual impression of an eye

- anomalous retinal correspondence: disturbances in the neurophysiological relationship system of both eyes

- subnormal binocular vision: reduced quality of binocular vision (e.g. reduced spatial vision)

- Horror Fusionis: irreparable central fusion disorder

- Deformities and maldevelopments of the visual organ

- Amblyopia: Functional amblyopia usually developed in early childhood, e.g. as a result of strabismus or anisometropia.

- Colour blindness: congenital absence of the function of one or more visual pigments

- Night Blindness

- Peters-Plus-Syndrome = Peters' anomaly

- Systemic diseases that also manifest themselves in the eye, e.g.:

- Diabetes mellitus: can damage almost all tissues of the eye, but diabetic retinopathy is the most common.

- Misperceptions as a result of circulatory disorders of the visual pathway, the visual cortex or the central nervous system (flickering scotoma, migraine, hallucinations)

- Flammer syndrome, a generalized disorder of vascular regulation which predisposes to normal tension glaucoma in the eye, but has also been described in association with retinopathy pigmentosa.

- Vascular occlusion as a result of arteriosclerosis.

- Horner syndrome: in case of damage of the sympathetic nervous system with typical triad of miosis, ptosis and apparent enophthalmos

- Marfan syndrome (genetically caused connective tissue disease with giant stature - prominent example: Abraham Lincoln -, typical: loosening of the eye lens, lens luxation)

- Marchesani syndrome (genetically caused connective tissue disease, loosening of the eye lens, lens luxation, short stature, skeletal malformations)

- Graves' disease (endocrine orbitopathy)

- Giant cell arteritis (also called arteritis temporalis, Horton's disease or arteritis cranialis). It is a vasculitis that can lead to blindness due to involvement of the central retinal artery (CAA) or anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION).

- Sjögren's syndrome (dry mucous membranes in the context of a mostly rheumatological disease)

- Disorders of the pupil due to diseases of the central nervous system

- Deviations of the optical image (ametropias) and near adaptability (accommodation) of the eye

- Ametropias (depending on their extent and cause, these are not regarded as actual diseases, but as physiological variants)

- Astigmatism: astigmatism

- Hyperopia: Farsightedness

- Myopia: nearsightedness

- Disturbances of accommodation

- Aphakia: loss of the natural lens (usually after cataract surgery or due to trauma)

- Hyper- and hypoaccommodation with and without disturbed AC/A quotient

- Ophthalmoplegia interna: isolated, internal oculomotor nerve palsy with absolute pupillary rigidity and paralysis of accommodation

- Presbyopia: physiological presbyopia, extensive loss of accommodation due to loss of elasticity of the lens

Search within the encyclopedia