Odyssey

![]()

This article is about Homer's epic poem; for other meanings, see Odyssey (disambiguation).

![]()

Nostos is a redirect to this article. For other meanings see Nostos (disambiguation).

The Odyssey (Ancient Greek ἡ Ὀδύσσεια hē Odýsseia), the second epic traditionally attributed to the Greek poet Homer alongside the Iliad, is one of the oldest and most influential poems in Western literature. The work was first recorded in written form probably at the turn of the 8th and 7th centuries BC. It depicts the adventures of King Odysseus of Ithaca and his companions as they return home from the Trojan War. In many languages, the term "Odyssey" has become synonymous with a long odyssey.

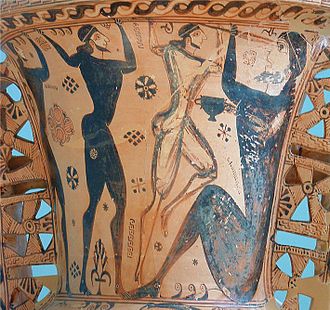

Odysseus and his companions dazzle Polyphemus. Detail of a Proto-Attic amphora by the Polyphemus painter, c. 650 BC, Museum of Eleusis, Inv. 2630.

The contents of the Odyssey

The Odyssey begins with the invocation of the Muse. The opening verses are reproduced here in ancient Greek, in transcription, as well as in the German translation by Johann Heinrich Voß from 1781, which is itself considered classical:

| Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ. πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσε-. πολλῶν δ' ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ' ὅ γ' ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κάτα θυμόν, ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. ἀλλ' οὔδ' ὣς ἑτάρους ἐρρύσατο ἱέμενός περ-. αὐτῶν γὰρ σφετέρῃσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὄλοντο, νήπιοι, οἳ κατὰ βοῦς Ὑπερίονος Ἠελίοιο. ἤσθιον- αὐτὰρ ὃ τοῖσιν ἀφείλετο νόστιμον ἦμαρ. τῶν ἁμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, εἶπε καὶ ἡμῖν. | Ạndra moi ẹnnepe, Moụsa, polỵtropon, họs mala pọlla plạnchthē, epeị Troiẹ̄s hierọn ptoliẹthron epẹrse: pọllōn d' ạnthrōpọ̄n iden ạstea kaị noon ẹgnō, pọlla d' ho g' ẹn pontọ̄ pathen ạlgea họn kata thỵmon, ạrnymenọs hēn tẹ psychẹ̄n kai nọston hetaịrōn. ạll' oud' họ̄s hetaroụs errhỵsato hịemenọs per; aụtōn gạr spheterẹ̄sin atạsthaliẹ̄sin olọnto, nẹ̄pioi, hoị kata boụs Hyperịonos Ẹ̄elioịo ẹ̄sthion; aụtar ho toịsin apheịleto nọstimon hẹ̄mar. tọ̄n hamothẹn ge, theạ, thygatẹr Dios, eịpe kai hẹ̄min. | Tell me, Muse, the deeds of the much-wandered man, Which so far erred, after holy Troy's destruction, ...seen many a city, learned many a custom.., ...and on the sea endured so much unnameable woe.., To save his soul, and his friends return. But friends he saved not, how eagerly he strove; For they themselves by iniquity prepared their destruction: Fools! Who have the cattle of the high Sunbeherschers Slaughtered; behold, the God took away from them the day of their return. Tell us a little of this, daughter of Kronion. |

In 24 cantos consisting of 12,110 hexameter verses, the Odyssey tells how the king of Ithaca, after the Trojan War which lasted ten years, was lost by adverse winds on his way home, wanders for another ten years, and after many adventures finally returns home unrecognized as a beggar. He finds his house full of aristocratic suitors who devour his property, persuade his wife Penelope that he is dead, and try to force her to marry one of their own. In a final adventure, Odysseus must do battle with these suitors. A parallel plot, the "Telemachia," tells how Odysseus' and Penelope's son Telemachus sets out to find his missing father.

The 24 songs

In order to maintain the tension at all times, Homer uses a very complex narrative style. He works, for example, with parallel plots, flashbacks, interpolations, changes of perspective and narrator. The plot is not told chronologically, but begins shortly before Odysseus returns to Ithaca. It is structured as follows:

- 1st to 4th song

The council of the gods decides to enable Odysseus to return home. To this end, the messenger of the gods Hermes is sent to the nymph Calypso, who has kept Odysseus on her island for seven years. Meanwhile, the goddess Athena goes to Odysseus' homeland of Ithaca, where his wife Penelope is besieged by numerous suitors to marry one of them. In the guise of her father's friend Mentes, Athena persuades Odysseus' son Telemachos to go in search of his missing father. The latter then sails to Pylos to see Nestor and then goes to Menelaos in Laconia to obtain information about his missing father. In the meantime, the suitors plan an assassination attempt on Telemachos and prepare an ambush on the island of Asteria between Ithaca and Samos.

- 5th to 8th chant

Hermes succeeds in persuading Kalypso to let Odysseus go. On a self-made raft Odysseus leaves Kalypso's island of Ogygia. But on the 18th day, when the Phaiak land is already in sight, his adversary, the sea god Poseidon, raises a storm that severely damages the raft and causes it to capsize. With the support of the nymph Ino Leukothea, Odysseus swims with his last strength to the coast of Sheria, the home of the Phaiaks. On the beach he meets the king's daughter Nausikaa, who shows him the way to her parents' palace. They welcome Odysseus hospitably.

- 9. to 12. Singing

In the central part of the epic, Odysseus tells the story of his odysseys in the house of the Phaiak king Alkinoos (see below: The odysseys).

- 13. to 16. singing

Now the two storylines, the teleachy and the Odyssey proper, are brought together. Odysseus returns home to Ithaca with the help of the Phaiaks, but must hide in the house of the faithful sowherd Eumaios until he can dare to fight the suitors. For his protection, Athena gives Odysseus the guise of a beggar upon his arrival in Ithaca. Meanwhile, Telemachos sets out from Sparta. Without staying overnight with Nestor, he goes straight to his ship after reaching Pylos in the evening and returns to Ithaca. He is able to escape the attack of the suitors of whom Athena has warned him. He goes to Eumaios and there meets his father Odysseus, whom he recognizes after being transformed back.

- 17. to 20. singing

Again in beggar's guise, Odysseus returns to his house after 20 years, where at first only his old dying dog Argos recognizes him, later also the old maid Eurykleia. Secretly, Odysseus prepares for battle with the suitors.

- 21. and 22. singing

In a bow fight Odysseus reveals himself and with the help of Telemachos and Eumaios kills the suitors as well as the maids and servants who have proved unfaithful.

- 23rd and 24th song

Odysseus sees his wife Penelope again after 20 years. But only after she has put him to the test with a ruse does she recognise him as her husband. Odysseus then visits his old father Laërtes. In the underworld, Achilles and Agamemnon, Odysseus' fellow fighters before Troy, praise his victorious return home. The goddess Athena settles the dispute between Odysseus and the relatives of the slain suitors.

The odysseys of Ulysses

A central role in the epic is played by cantos 9 to 12, in which Odysseus describes his adventures up to his arrival at the Phaiaks. This rather fairy-tale-like part is considered by many scholars to be the original epic, which was later expanded to include the introductory telemachia and the detailed account of the suicide at the end.

Kikons, Lotophages and Cyclopes

After leaving Troy on twelve ships, Odysseus and his companions first attack the Thracian Kikons, who are allied with the Trojans, but are driven off by them. As the ships round Cape Malea, the southern tip of the Peloponnese, on their way to Ithaca, a strong north wind comes up and drives them, past the island of Kythera, out to sea. Eventually they reach the land of the Lotophagi, the lotus-eaters. Three companions, whom Odysseus sends as scouts to the Lotophages, taste of the fruit, which makes them forget their homeland and desire to stay in the land of the Lotophages forever. They then have to be taken back to the ships by force.

Afterwards, Odysseus and his companions land on an island where many wild goats live. The following day, they cross to the nearby opposite coast, which is populated by giants, the Cyclopes. One of them, the one-eyed Polyphemus, captures Odysseus and twelve of his companions who have entered his cave. He kills and eats a total of six of them and threatens to eat the rest as well as Odysseus one by one. Since the Greeks do not have enough strength to move the rock with which Polyphemus has blocked the entrance to the cave, they cannot kill the Cyclops, but must outwit him. Thus Odysseus, asked by Polyphemus for his name, introduces himself as Oútis (Οὖτις) "Nobody." He succeeds in getting Polyphemus drunk and then blinding him with a red-hot stake. When other Cyclopes rush over in response to Polyphemus' cries of pain, he shouts to them that "Nobody" has done something to him, so they turn back. To let his sheep out to pasture, Polyphemus rolls away the stone in front of his cave in the morning, but feels the animals' backs to prevent the Greeks from mingling with the flock. However, by tying three sheep together at a time, with one man clinging to each belly, Odysseus and his companions are able to escape. When Polyphemus notices their escape, he hurls rocks in the direction where he thinks the ships are, but misses them. Haughtily, Odysseus reveals his true name to Polyphemus. In his anger, Polyphemus asks his father Poseidon to let Odysseus perish at sea, or at least to delay his return for a long time.

Aiolos, Laistrygonen, Kirke

The wind god Aiolos, whose island he is heading for next, gives Odysseus a leather tube in which all the winds are locked up except the west wind, which is supposed to drive his ships safely to Ithaca. But when Odysseus' unsuspecting companions open the hose out of curiosity shortly before reaching their destination, all the winds escape and their ships are driven back to the island of Aiolos. The latter then refuses any further help.

Next, Odysseus and his people arrive at Telepylos to the Laistrygons, a giant man-eating people. When their king impales one of two scouts, the Greeks try to flee, but their ships are crushed by boulders in the harbor, which reaches far into the country, by the Laistrygons rushing in from all sides. Only Odysseus manages to escape with his ship and its crew, as he took the precaution of not allowing it to enter the harbour. All the other ships are lost.

With his last ship, Odysseus reaches the island of Aiaia, where the goddess and sorceress Kirke lives with some servants. At her estate are enclosures of tame lions and wolves, in reality humans who have been enchanted by Kirke. Kirke also transforms half of Odysseus' men, whom he has sent out to explore the island, into pigs with a magic potion. Only Eurylochos, who has not entered Kirke's house out of an abundance of caution, escapes to the ship. When Odysseus then goes to Kirke alone, he meets Hermes, the messenger of the gods, who gives him the herb Moly. With its help, he manages to resist the spell. Moreover, Odysseus forces Kirke to swear that she will do no more harm to him or his companions. She turns the companions back into men and shares her camp with Odysseus. After a year, Odysseus, at the urging of his companions, decides to continue his journey home, despite Kirke's courtship.

The sorceress advises him to first consult the soul of the seer Teiresias in the house of Hades, Homer's designation of the underworld, about his further fate. There Odysseus makes a sacrifice and the souls of his mother, who has died in the meantime, of fellow fighters from the Trojan War and of his companion Elpenor, who died in an accident on Aiaia, appear to him. The seer Teiresias gives him advice for the onward journey.

Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis

After visiting the underworld, Odysseus and his companions first return to the island of Kirke to bury Elpenor, who fell to his death immediately before setting off for Hades. Kirke gives Odysseus advice for the journey home, points out the dangers of Scylla and Charybdis as well as an equally dangerous alternative route through the planets, and warns him - like Teiresias before him - not to slaughter the cattle and sheep on the island of Helios. Odysseus and his companions then leave Aiaia. The journey first takes them past the island of the Sirens, whose beguiling songs lure sailors onto the cliffs and thus to their deaths. In order to be able to listen to them safely, Odysseus, on Kirke's advice, has himself tied to the mast tree, but has his companions' ears sealed with wax. They then pass a strait whose shores are ruled by two sea monsters, namely the six-headed, man-devouring Scylla and Charybdis, who causes a whirlpool in which entire ships sink. Odysseus has his companions row as far away as possible from Charybdis and thus close to Scylla, which devours six of them.

Helios, Kalypso and the Phaiaks

Weary, they soon reach Thrinakia, the island of the sun god Helios. Adverse winds prevent them from continuing their journey for a month, and after their supplies are exhausted, they begin to suffer from hunger. Therefore, despite Odysseus' warning, the companions slaughter Helios' sacred cattle. As punishment, they perish after their departure in a storm sent by Zeus at Helios' insistence. Only Odysseus, sitting on the keel of his ship, is able to save himself on the island of the nymph Calypso, Ogygia.

Calypso holds Odysseus for seven years and only lets him go at the behest of the gods. With her help, he builds a raft and after 17 days reaches within sight of the coast of Sheria, the land of the Phaiaks. When Poseidon sees Odysseus, he unleashes a storm that severely damages the raft and causes it to capsize. The nymph Ino Leukothea, however, notices the castaway and takes pity on him. She gives him a veil to tie around himself and advises him to leave his unmanoeuvrable raft. Carried by the veil, he reaches the coast swimming and with great effort.

There Nausikaa, the daughter of King Alkinoos, finds him naked on the beach. She provides Odysseus with clothes and shows him the way to her parents' palace. He succeeds in winning the favor of Alkinoos and his wife Arete, who promise to have him brought to Ithaca in one of their ships. The Phaiaks hold games in his honor and give him rich gifts. When the singer Demodokos recites songs about the Trojan War, Odysseus cannot hold back his tears. Alkinoos notices this and asks the guest to reveal his identity and the cause of his grief. In response, Odysseus recounts his experiences. Finally, Odysseus, presented with more precious gifts, is escorted to the ship that will take him to Ithaca.

The "tall tales" of Ulysses

In addition to the detailed account of his wanderings among the Phaiaks, Odysseus also tells a few made-up stories after his return to Ithaca in order to conceal his true identity - mostly out of caution.

To Athena, who meets him in the form of a young man shortly after landing on Ithaca, Odysseus states in the 13th canto that he comes from Crete. There he had slain Orsilochos, the son of Idomeneus. He went with him to the Trojan War, but not under Idomeneus' leadership, but with his own companions. Orsilochos had wanted to rob him of all the booty from Troy after his return. Therefore he had waylaid Orsilochos at night and killed him with a spear. Afterwards he had immediately gone to a Phoenician ship and offered the Phoenicians a part of his booty in exchange for their taking him to Pylos or Elis. Off the west coast of the Peloponnese, however, the wind drove them away and they arrived at Ithaca. While Odysseus slept on the shore, the Phoenicians unloaded his treasures and sailed to Sidon without him.

In the 14th canto, Odysseus tells the sowherd Eumaios an initially similar, but then greatly differing and longer tall tale, which also takes into account the time gap between the fall of Troy and his arrival on Ithaca: Again, Odysseus claims to be from Crete and to have been the leader of a Cretan contingent in the Trojan War. He pretends to be the son of a rich man and a slave girl, but was loved by his father as much as his legitimate sons. After his father's death he (Odysseus) was compensated by his half-brothers only with a very small part of the inheritance and a house, but thanks to his efficiency and his courage in battle he made it to reputation and wealth. Battles and sea voyages with companions from the hinterland had been dearer to him than domestic work, and he had been very successful in raids. For this reason he was chosen, along with Idomeneus, to lead the Cretans against Troy. After his return from Troy, he was drawn away again after only one month and sailed with some ships to Egypt. Contrary to his order to wait and send out scouts, his companions began to plunder, abduct women and children, and kill Egyptian men. Thereupon, he says, an Egyptian king gathered an army in a nearby town, attacked the Greeks at dawn, and crushed them. Odysseus reports that he threw himself at the feet of the king. The king forgave him and in the following seven years he made a great fortune in Egypt. After that, a deceitful Phoenician persuaded him to come with him to Phoenicia. After a year's stay in Phoenicia, this man had lured him under a pretext onto a ship bound for Libya, with the intention of selling him there. After the ship had passed Crete, it capsized in a storm. Odysseus goes on to say that he clung to a mast and after ten days was driven to the coast of the Thesprots. The Thesprotian king Pheidon took him in and instructed companions to escort him by ship to Dulichion to King Akastos. The Thesprotian sailors, however, planned servitude for Odysseus, stripped him of his clothes and put rags on him, and bound him. At a stopover on Ithaca, he managed to free himself and hide on the island until the Thesprotians moved on. Odysseus also tells in this tall tale that Pheidon hospitably received Odysseus, who then went to Dodona to consult the Zeus oracle there about the most favorable way home to Ithaca. Since then, however, Odysseus had been far away for a long time.

In the 19th canto, Odysseus, still in the guise of a beggar, tells his wife Penelope a tall tale: He claims to be called Aithon, to come from Crete, and to be the younger brother of Idomeneus. When Idomeneus was already on his way to Troy, Odysseus was stranded with his ships on the coast of Crete. He had entertained him and his companions for eleven days, as northerly winds had prevented Odysseus from continuing his voyage, and had prepared gifts for Odysseus as he continued towards Troy. After Penelope put the supposed Aithon to the test and he truthfully told her Odysseus' robes and the appearance and name of his herald Eurybathes, Penelope wept bitterly for the husband she had thought dead. Thereupon Odysseus urges her not to weep, claiming that he has learned that Odysseus is still alive. The latter had lost his ship and all his companions off Thrinakia, but had reached Thesprotia, richly gifted by the Phaiaks, as he had learned from King Pheidon. In what follows the story resembles that which he told Eumaios.

In the 24th canto, immediately before he reveals himself to his father Laertes, Odysseus claims to be from the city of Alybas in Sicily, to be called Eperitos, and to have been whisked away to Ithaca in his ship. He claims that Odysseus has been staying in Sicania and left from there five years ago on a ship bound for home.

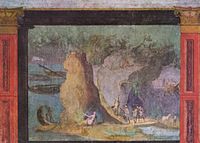

The companions of Odysseus rob the cattle of Helios (Pellegrino Tibaldi)

Odysseus and his companions dazzle Polyphemus. Laconic black-figure bowl by the equestrian painter, ca. 565-560 BC.

Kirke hands Odysseus the drinking cup. Painting by John William Waterhouse (1891)

Roman fresco of the Odyssey (now in the Bibliotheca Apostolica of the Vatican), c. 150-100 BC.

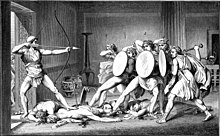

Odysseus shoots his opponents

.jpg)

Odysseus hands the Cyclops Polyphemus a bowl of strong wine

Pieter Lastman, Odysseus and Nausikaa, oil portrait, 1619, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Textual tradition

The transmission of the text as written by the poet of the Odyssey in the late 8th or 7th century BC is not entirely certain, even for antiquity. Of the Odyssey, as of the Iliad, many divergent copies are likely to have been in circulation shortly after its writing. However, the high esteem in which the Homeric texts were held early on meant that text-critical reconstructions of the original version were repeatedly produced; in the Athens of the tyrant Peisistratos at the end of the 6th century BC, this was even done at state expense. Until early Hellenistic times, however, papyri show versions of the text that differ from each other and from the Athenian version.

This changed only after the founding of the Library of Alexandria by Ptolemy I Soter in 288 B.C. The scholars Zenodotos of Ephesus, Aristophanes of Byzantium, and especially Aristarchus of Samothrace, the sixth head of the library, produced canonical versions of both epics through comparisons and text-critical methods, which probably corresponded to the Athenian versions. Although in the course of time the writings of the three library rulers were also largely lost, the copies of both epics up to the end of antiquity and their present textual form can be traced back with some certainty to their work.

This can be explained above all by the aforementioned veneration of Homer throughout the ancient world. The Odyssey and the Iliad belonged to the core of the ancient educational canon, and since the activity of the Alexandrian librarians, care was taken to pass on the texts faithfully. However, complete copies of both works from antiquity have not survived.

The oldest fragmentary textual evidence includes the London Homer Papyrus from the first half of the 2nd century and the Berlin Homer Papyrus from the 3rd century. In July 2018, the Greek Ministry of Culture announced that German and Greek archaeologists had found a clay tablet containing 13 verses from the 14th canto of the Odyssey in ancient Olympia, which initial estimates suggest may date from the Roman period before the 3rd century.

The oldest surviving manuscript of the Homeric complete works comes from 12th century Constantinople. The Greek humanist Demetrios Chalcocondyles was responsible for the first printing of the epics in Florence in 1488. This incunabulum was followed by another printed edition by the Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius in 1504. Thus, almost 2000 years lie between the first written record of the Homeric epics and the earliest text versions, which have been preserved in their entirety to this day. Nevertheless, researchers assume that today's versions essentially correspond to Homer's version thanks to the preparatory work of the ancient scholars.

Book 5, verses 319-350 of the Odyssey (with scholia) in the manuscript written in 1335/1336 Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vaticanus Palatinus graecus 7, fol. 46v

Questions and Answers

Q: What is The Odyssey?

A: The Odyssey is a major Ancient Greek epic poem.

Q: Who is the author of The Odyssey?

A: The author of The Odyssey is Homer.

Q: Who is the hero of The Odyssey?

A: The hero of The Odyssey is Odysseus, or Ulysses as he is called in Latin.

Q: Is The Odyssey a historical or mythological poem?

A: The Odyssey is a mythological poem, not a historical one.

Q: What is the subject of the Iliad?

A: The subject of the Iliad is the Trojan War.

Q: How long is Odysseus's voyage home to Ithaca?

A: Odysseus's voyage home to Ithaca takes ten years.

Q: What are some of the dangers Odysseus and his men encounter during their journey in The Odyssey?

A: Odysseus and his men encounter monsters and many other dangers such as fighting off men who want to marry Penelope, Odysseus's wife, and Telemachos, Odysseus's son, searching for his father during their journey in The Odyssey.

Search within the encyclopedia