October Revolution

![]()

This article is about the Russian Revolution in October 1917, for other October uprisings see October Uprising.

The October Revolution (Russian Октябрьская революция в России, Oktyabrskaya revolyuziya v Rossii) of 25 Octoberjul. / 7 November 1917greg. was the violent seizure of power in Russia by the Communist Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. It eliminated the dual rule of the socialist-liberal Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky and the Petrograd Soviet that had emerged from the February Revolution. It led to several years of civil war and, after its end in 1922, to the founding of the Soviet Union, a dictatorship of the Russian Communist Party.

In real socialist countries usually called the Great October Socialist Revolution (Russian Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция Velikaja Oktjabr'skaja socialističeskaja revolucija) and glorified as a turning point in human history, the opponents of the Bolsheviks regarded the October events as a mere coup d'état, the results of which were consolidated only after a bloody civil war.

The term October Revolution was deliberately coined in order to elevate the event in comparison to the preceding February Revolution, which had after all brought about the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the end of the Russian monarchy. The designation of both events after the months of February and October is based on the Julian calendar still used in Russia at that time. According to the Gregorian calendar used in the rest of Europe, which was 13 days ahead of the Julian calendar but was not introduced in Russia until January 1918, both events fell in the respective following months. Therefore, the anniversary of the October Revolution in the Soviet Union was always celebrated on November 7.

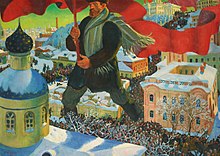

The Bolshevik , oil painting by Boris Kustodiev (1920)

The overthrow

Preparation

There was a dispute among the leadership of the Bolshevik Party as to whether it should participate in the elections to the Constituent Assembly or instead rely on violent insurrection. Lenin, in his Finnish hideout, urged the party to assume sole governmental power, believing the time was right to exploit the government's weak position. In a letter in mid-September he wrote:

"It would be naive to wait for a 'formal' majority of Bolsheviks. No revolution waits for that. Kerensky and Co. are not waiting either; they are preparing to hand over Petrograd [to the Germans]. The very miserable vacillations of the Democratic Conference must and will break the patience of the workers of Petrograd and Moscow! History will not forgive us if we do not seize power now."

Most of the other leading Bolsheviks, however, were in favor of transferring power democratically to the soviets and wanted to wait for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets for this purpose. All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which had been convened for 20 Oct. Jul. / 2 Nov. 1917greg. Although the Central Committee had instructed him to remain in Finland, Lenin secretly returned to Petrograd on 9 Oct. yul. / 22 Oct. aggreg. At two Central Committee meetings on 9 Jul. / 22 Oct. aggreg. and on 15 Jul. / 28 Oct. aggreg. he was able to win the majority of the party leadership to his side: He was opposed only by Grigory Zinoviev (1883-1936) and Kamenev, who denied that the conditions for socialist revolution were already in place and feared that an insurrection begun too soon would be crushed. Enraged, Lenin retorted that to wait was "consummate idiocy or consummate treason." One should not be guided "by the mood of the masses; it is fickle and cannot be accurately calculated". On the contrary, it was necessary to present the All-Russian Congress with a fait accompli and have it legitimize the revolution. The Central Committee finally adopted, by nineteen votes to two, a resolution committing all party cadres to "prepare all-sidedly and energetically for the armed insurrection." To organize the uprising, a center was formed of Andrei Bubnov (1883-1938), Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926), Moissei Uritsky (1873-1918), Yakov Sverdlov (1885-1919), and Josef Stalin. No date was given; "the day of the uprising," Stalin is reported to have said, "is determined by circumstances." On 16 Jul/29 Octgreg the date of the II All-Russian Congress of Soviets was postponed by the moderate socialist groups to 25 Oct Jul/7 Nov 1917greg. They apparently wanted to give Kerensky time to act against the Bolsheviks before then. But without this postponement, Lenin's intention to take power before the Soviet Congress convened could not have been realized.

This military-revolutionary center, however, had only symbolic significance. The real strategist of the overthrow was Leon Trotsky. By decision of the Petrograd Soviet, he had set up a military organization, the Military-Revolutionary Committee (MRC), on 8 Oct. Jul. / 21 Oct. 1917greg. Lenin later wrote:

"After the Petrograd Soviet passed into the hands of the Bolsheviks, Trotsky was elected its chairman, and in this capacity he also organized and led the October 25 uprising."

Pro forma, the MRK was meant to prepare the city's defense against counterrevolution; in reality, it served to thwart the transfer of revolutionary troops to the front, which Kerensky had ordered a few days earlier. The soldiers saw this not as a contribution to the defence of the fatherland, but as an attempt to remove revolutionary elements from Petrograd. Thus the MRK became the instrument of the Bolsheviks' military seizure of power. The troops were limited to some 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers from the Petrograd garrison, the Kronstadt navy, who had subordinated themselves to the Military-Revolutionary Committee, the Red Guards, and a few hundred detachments of militant Bolsheviks drawn from the workers' committees. According to other accounts, they had only 6,000 men.

On 22 Oct. Jul. / 4 Nov. 1917greg. the commander of troops of the Petrograd district refused to place his staff under the control of the commissars of the MRK. Thereupon, at the instigation of Trotsky and Sverdlov, it assumed command of the capital's garrisons. From now on the Military-Revolutionary Committee inspected all barracks, arsenals and staff posts in the city, all military orders had to be countersigned by it. The transfer of troops ordered by Kerensky on 20 Oct. Jul. / 2 Nov. 1917greg. was thus prevented.

Military coup

Kerensky was aware that the Bolsheviks and the MRK were now openly posing the question of power. As a first countermeasure, he ordered the closure of all Bolshevik printing plants on the night of 24 Oct. Jul. / 6 Nov. 1917greg. Thus he gave Trotsky the pretext to strike out. On that day units of the MRK, supported by the Red Guards, occupied strategic points in the city. This was not noticed until later in the day, when it was reported in the commandant's office that no more orders were being carried out. Kerensky then fled to headquarters in Tsarskoye Selo to organize loyal troops to regain power. There, however, he fell on deaf ears because several of the generals loyal to the Tsar hoped for a Bolshevik coup that would soon collapse and clear the way for a dictatorship they sought.

Meanwhile, at a meeting of the Petrograd Soviet in the Smolny Institute, Trotsky and Lenin declared that the Kerensky government had been overthrown, that power was in the hands of a Revolutionary Military Committee and that the "victorious uprising of the proletariat of the whole world" was imminent. During the day the first posters also informed of the change of power. Around the Winter Palace, where the remnants of the Provisional Government were meeting, there were some exchanges of fire, with which the loyal soldiers also repelled looters. Then during the night a blind shot was fired at the seat of government from the Peter and Paul Fortress, located on the other bank of the Neva, and the cruiser Aurora also fired shots without doing any lasting damage to the building. When it became clear during the night that resistance was no longer to be expected, members of the MRK occupied the Winter Palace, which they entered through the unlocked main gate. They arrested the assembled ministers, later releasing them after they signed a statement that they would withdraw from politics. The student officers gathered for their protection were sent home on assurances of goodwill, and some members of a women's battalion, accused of firing on the MRK members, were imprisoned, abused, and in some cases raped. Thus the city was completely in the hands of the Bolsheviks.

The term "Storming of the Winter Palace", which persists in the collective memory, goes back to the bestseller Ten Days that Shook the World by the American journalist John Reed, who was present at the arrest of the government members. It was intended to place the October Revolution on a par with the French Revolution with the Bastille Storm, but represents a strong dramatization of the action, which on the whole was less than spectacular.

The overthrow was less peaceful in Moscow, where the Bolsheviks were only able to prevail after a week of bloody fighting. Several hundred people were killed and part of the Kremlin was damaged. But here too the decisive factor was the passive behaviour of the garrison, which refused to take up arms for the February regime. In the rest of the country, the transfer of power was similarly peaceful as in Petrograd, as often local groupings of the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries were willing to cooperate.

The II All-Russian Congress of Soviets

At the II All-Russian Congress of Soviets (II Russian Всероссийский съезд советов; transcription: Vtoroi Vsjerossijski sjesd sowjetow), which opened late in the evening of 25 Oct. Jul. / 7 Nov. 1917greg. after some temporizing by Lenin, the Bolsheviks held 300 of the 670 seats. The Social Revolutionaries provided 193 delegates, many of whom belonged to the left wing of the party, which cooperated with the Bolsheviks. The Mensheviks had 82 seats, the remaining delegates belonging to smaller socialist groups. The vast majority, 505 delegates, agreed to the slogan "All power to the councils!" on a questionnaire distributed in advance, but whether this was accompanied by agreement to military action by the Bolsheviks was by no means a foregone conclusion. The Menshevik and Social Revolutionary delegates who opposed it were not united among themselves and made it easy for the Bolsheviks by resorting to a boycott strategy: in protest, the Mensheviks refrained from taking the four seats on the Congress Executive Committee to which they were entitled; eventually, more and more Menshevik and Social Revolutionary delegate groups left the meeting hall in protest. The stenotypists also stopped work, which is why there are no minutes of the congress. Trotsky sneered after the Menshevik politician Martov:

"The uprising of the masses needs no justification. What happened was an uprising and not a conspiracy. [...] The masses of the people followed our banner, and our uprising was victorious. And now they propose to us: Renounce your victory, agree to concessions, make a compromise. With whom? I ask: With whom shall we make a compromise? With miserable groups who have gone out or who are making this proposal? [...] After all, behind them there is no one left in Russia. No, there is no compromise possible here. To those who have gone out and to those who are making proposals to us, we must say: you are pitiful bankrupts, your role is played out; go where you belong: to the dustbin of history!"

Late in the evening Lenin appeared, whom most of the delegates saw for the first time in their lives. He read out the so-called overthrow decrees: the Decree on Peace, which offered an immediate opening of negotiations for a "just peace" on condition of a general renunciation of annexations and war reparations, and the Decree on Land, which expropriated large estates without compensation, thus legitimizing land appropriation by the peasants, much of which had already taken place. The delegates, to whom the texts had not been submitted in writing, voted unanimously or by a large majority. On the morning of 26 Oct. Jul. / 8 Nov. 1917greg. the Congress also acclaimed the decree on the establishment of the Council of People's Commissars, the new government of Russia, of which Lenin became the head. The assembly sang the International and dispersed.

The Small Nikolai Palace in the Kremlin, damaged during the fighting.

Members of the women's battalion that defended the Winter Palace

Cruiser Aurora

.png)

Leon Trotsky. Passport photograph in a French travel document, 1916 or 1917

Russian soldiers at a demonstration in Moscow in early November 1917, the banner has the inscription "Communism".

After the overthrow

council of people's commissioners

→ Main article: Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR

The Council of People's Commissars (Russian Совет Народных Комиссаров; Soviet Narodnych Komissarov, abbreviated Zovarkom) was to be grassroots, non-bureaucratic, and flexible, according to the decree that established it as the government. To this end, it was to rely on "commissions" to provide technical expertise and be responsible to the All-Russian Soviet Congress and its Executive Committee. In reality, these commissions were never established; rather, the People's Commissars moved into the previously existing ministries and largely took over their civil service apparatus. More than half of the employees and civil servants in the Sownarkom authorities had already worked there before the October coup. Nor did effective control by the Soviets materialize. Instead, the People's Commissars followed the dictates of the Bolshevik Party, which had not even been mentioned in the founding decree.

The Sovnarkom initially consisted only of Bolsheviks. Important portfolios were held by Trotsky (Foreign Affairs), Stalin (Nationalities), Alexei Rykov (1881-1938; Interior), Vladimir Milyutin (1884-1937; Agriculture) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko (1883-1938), Nikolai Krylenko (1885-1938) and Pavel Dybenko (1889-1938): the latter three were collectively responsible for the military and navy. After successful coalition negotiations, seven Left Social Revolutionaries moved into the government on Dec. 9-Jul. 22, 1917greg. Lenin and the People's Commissars set about the work of government with great zeal - by the end of 1917 alone they had issued 116 different decrees. Most of these were handwritten by Lenin himself. From 1917 to 1922 he is said to have written, dictated or edited a total of 676 laws, decrees and instructions, an "incredible workload", as Gerd Koenen comments.

- On 27 Octoberjul. / 9 November 1917greg. censorship was reintroduced. The Sovnarkom passed the decree on the press, which provided for the closure of all newspapers that called for disobedience to the new government. This was tantamount to banning all press organs of the non-socialist parties in Russia.

- The Decree on Workers' Control of 1 November-Jul. / 14 November 1917greg. established workers' control of industrial enterprises. Since the envisaged cooperation between enterprises and workers did not work, nationalizations were the result, contrary to the text of the decree. This process was already completed by the middle of 1918, and since then all of Russia's industrial enterprises have been in state hands.

- In the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia of 2 Novemberjul/15 November 1917greg. all the peoples of Russia were granted the right of self-determination, all forms of national and religious discrimination were abolished.

- On 2 Novemberjul. / 15 November 1917greg. the privileges of all Christian confessions were abolished, and on 11 Decemberjul. / 24 December 1917greg. religious instruction in schools. This was followed on 20 Januaryjul. / 2 February 1918greg. by the law on the separation of church and state. After a brief and relatively quiet period of consolidation, all denominations and religious communities were massively persecuted. The security authorities arrested numerous pastors, committed laymen, and ordinary believers; a large number of them perished in camps, among other places. See also Religion in the Soviet Union.

- On 24 Nov. Jul. / 7 Dec. 1917greg. the Extraordinary Commission for the Struggle against Counterrevolutionaries and Sabotage (abbreviation: Cheka) was founded under the leadership of Dzerzhinsky. The aim of this secret police was the elimination of political opposition through terrorist violence and the nationwide enforcement of the party's monopoly on power. It worked to the so-called revolutionary tribunals, since it was not allowed to pass or execute sentences until the decree of September 26, 1918. Soon it was used not only against the opposition, but also against speculation and corruption.

- A decree of 28 November-Jul. / 11 December 1917greg. ordered the arrest of the leaders of the Cadets, who were the only non-socialist party with a mass following, "as a party of enemies of the people".

The dissolution of the Constituent Assembly

→ Main article: Russian Constituent Assembly

Although the Bolsheviks could not be sure of obtaining a majority, they nevertheless set the elections to the Constituent Assembly for 29 Octoberjul/11 November 1917greg. These should originally have taken place in September, but the Provisional Government had postponed them, from which the Bolsheviks' propaganda had profited argumentatively. Lenin had already argued for another postponement of the elections on the day of the coup, but had been overruled by the CC and Executive Committee.

In the elections 48.4 million votes were cast, the turnout is estimated at about 60 %. The Social Revolutionaries became the strongest party with 19.1 million votes, followed by the Bolsheviks with 10.9 million votes - the greatest electoral success in their history, but nevertheless a heavy defeat, since the ruling party was distrusted by more than half of the voters. The Cadets received 2.2 million votes, the Mensheviks 1.5 million, and the non-Russian socialist parties more than 7 million, most of them from Ukraine. In the morning, after a demonstration by a "Committee for the Defence of the Constituent" had been shot up by Kronstadt sailors on Dybenko's orders, the Constituent Assembly met in the Taurian Palace on 5 Jan. Jul. / 18 Jan. 1918greg. The deputies rejected the Bolsheviks' motion to accept Soviet power as a given and instead followed an agenda proposed by the Social Revolutionaries. Their founder, Victor Chernov (1873-1952), was elected speaker of parliament. A continuation of their work was prevented by Bolshevik military force by force of arms the following day. By way of justification, the Sovnarkom, in its decree of January 6/January 19, 1918greg. pointed to the fact that in the meantime the Left Social Revolutionaries, who had been part of the coalition government, had also split off organizationally from the rest of the party: At the time of the election, therefore, the people had not been able to distinguish between the two at all. Moreover, only class institutions like the soviets, and not representatives of all the nation's citizens, were in a position to "break the resistance of the propertied classes and lay the foundations of socialist society.

The establishment of Bolshevik autocracy

Since the rule of the soviets was a very popular idea, its expansion over large parts of the country was quite easy. Where the Bolsheviks could not count on a cohesive industrial workforce, as in Petrograd, Moscow or the mining districts of the Urals, they relied on the garrisons. The spread of the revolution was more difficult in rural areas, where the village soviets competed with the traditional self-governing units, the semstvos, in which social revolutionaries dominated. By the beginning of spring 1918, soviets existed in over 80% of all localities in Russia. The seizure of power by local soviets was combined with the socialization of the means of production and the elimination of real or suspected opponents. The disorderly violence that accompanied this process was quite deliberate on the part of the Bolsheviks. Thus, in December 1917, in his posthumously published pamphlet How to Organize Competition, Lenin described as a common goal the "cleansing of the Russian soil of all vermin, of the fleas-the crooks, of the bugs-the rich, etc., and so on." The manner of this cleansing may well be different:

"In one place they will put ten rich people, a dozen crooks, half a dozen workers who shirk work [...] in jail. In another place they will be made to clean the lavatories. In a third place, after they have served their prison sentences, they will be given yellow passports so that the whole nation may watch them as harmful elements until they are reformed. In a fourth place, one in ten who are guilty of parasitism will be shot on the spot."

In the late winter of 1918, the coalition of the Bolsheviks, who had shortly before renamed themselves the Russian Communist Party (B), with the Left Social Revolutionaries disintegrated. The occasion was the dispute over the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty, which the People's Commissar for External Affairs Trotsky had signed on March 3, 1918-a dictatorial peace that required Russia to unilaterally demobilize its army and relinquish its Finnish, Courland, Lithuanian, Polish, and Ukrainian territories. It thus lost more than one-third each of its population, agricultural land, and railroad network, as well as three-quarters of its deposits of coal and iron ore, and virtually all of its tapped oil reserves and acreage of cotton. This no longer seemed acceptable to the patriotic Left Social Revolutionaries. Having failed to prevail against the Bolsheviks at the Fifth All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which met at the Bolshoi Theatre on July 4, 1918 (in March 1918 the Sovnarkom had moved the capital to Moscow ahead of the approaching German troops), they reverted to the method of individual terror which had distinguished the Social Revolutionaries before 1917. On July 6, 1918, they assassinated the German ambassador Wilhelm von Mirbach-Harff, triggering the revolt of the Left Social Revolutionaries, which was bloodily put down and led to the banning of the party.

Moderate Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had already been declared counterrevolutionary by the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets on June 14, 1918, whereupon members of these parties were expelled from all Soviet organs. This amounted to a ban on these parties: from the summer of 1918, Russia was a one-party regime.

On July 8, 1918, the III All-Russian Congress of Soviets adopted a constitution for Soviet Russia. It was to be valid only for a transitional period and was based on a draft by Lenin in January 1917. Russia was declared to be a federal republic of soviets of workers', soldiers' and peasants' deputies, to whom all state power belonged. There was no separation of powers. Article 9 stipulated:

"The main task [...] consists in the establishment of the dictatorship of the urban and rural proletariat and of the poorest peasantry in the form of the powerful all-Russian Soviet power for the complete suppression of the bourgeoisie, for the abolition of the exploitation of man by man, and for the establishment of socialism, under which there will be neither division into classes nor state power."

The right to vote applied irrespective of origin, religious affiliation or gender, but was limited to people who "earned their livelihood from productive and socially useful work" or were in dispute. The executive was the Sovnarkom, whose decisions could be suspended at any time by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. On the other hand, a Bolshevik circular letter of May 29, 1918, showed how far off this distribution of power really was: "Our party stands at the head of Soviet power. The decrees and measures of Soviet power emanate from our party."

Civil War

→ Main article: Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War had already begun in January 1918 with the uprising of the Don Cossacks under General Alexei Kaledin (1861-1918). In it, national, political, social and religious lines of conflict overlapped to form an economic and humanitarian catastrophe of unheard-of proportions. Between 1918 and 1922, 12.7 million people died on the territory of the former Russian Empire, compared with 1.85 million in the First World War. More than half of the civil war victims died of hunger or epidemics. A major victim group were the Jews in Russia, who were persecuted and murdered mainly by opponents of the Bolsheviks. It is estimated that about 125,000 people fell victim to these pogroms. Over 20,000 Jews emigrated to Palestine ("Third Aliyah").

Russia disintegrated into various unstable units that fought each other to the death, brutalization was general on all sides. Here the national secessions in the West and in the Caucasus are to be mentioned, German troops advanced as far as Kharkov, the Social Revolutionaries established a short-lived dominion of their own in Samara on the Volga (Komutsch), anarchists around Nestor Machno (1888-1934) defended a "free rayon" in eastern Ukraine for several years, Green armies and the peasants of Tambov resisted forced grain requisitions under wartime communism, the Czechoslovak Legions fought their way along the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok, British, French, American and Japanese intervention forces occupied the ports of Odessa, Vladivostok, Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. The decisive centres of power, however, were the "Red" dominions of the Bolsheviks in central Russia and the "White" dominated areas in southern Russia and Siberia. These were right-wing military leaders such as Anton Denikin (1872-1947), Alexander Kolchak (1874-1920), Pyotr Wrangel (1878-1928) or Nikolai Yudenich (1862-1933), who sought a restoration of the monarchy or a military dictatorship. Because they were at odds with each other, because they did not want to make firm commitments to the rural population on the agrarian question, and because of the weak infrastructure of the areas they ruled, they were structurally inferior to the "Reds".

A major factor in the Bolsheviks' victory was the establishment of the Red Army, which Trotsky set up beginning in January 1918. He used former tsarist officers as advisers, whose families he held hostage in order to secure their loyalty. On May 29, 1918, conscription was also reintroduced, rank insignia, military forms of salute, disciplinary sanctions up to and including the death penalty were added. Trotsky proved to be a gifted military strategist, rushing from theater of war to theater of war with his famous railroad train, taking advantage of the inside line.

Another success factor proved to be the Red Terror, which the Sownarkom decided on September 5, 1918. The occasion had been two assassinations. On August 30, 1918, Moissei Uritsky, who had resigned from the Sovarkom in protest against the peace of Brest-Litovsk and was now working as Petrograd's Cheka chief, fell victim to the bullets of a former cadet seeking revenge for the execution of friends; at the same time, Lenin narrowly escaped a revolver attack on him by the social revolutionary Fanny Kaplan. The Sovnarkom then declared it necessary "to rid the Soviet Republic of class enemies, for which reason they are to be isolated in concentration camps. All persons related to White Guard organizations, conspiracies and insurrections are to be shot." The Cheka's repressive apparatus was expanded, and its extrajudicial powers were increased. The death penalty, which the Bolsheviks, like all socialist parties, had hitherto consistently rejected, became a normal means of repressing class enemies, a term which included not only industrialists, landowners, priests or cadets, but also workers and peasants. The decision remained in force until 1922; it is estimated that several hundred thousand people fell victim to the Red Terror.

During the period of the Civil War, the new government also waged wars against Poland, Finland (27 January to 5 May 1918) and Latvia. After the end of the Civil War, the independent power of the Soviets was not restored, which was opposed by the Kronstadt sailors' uprising in March 1921. The sailors, who had sided with the Bolsheviks during the upheaval, now demanded free elections to the soviets and the restoration of freedom of speech, press, and association. The Bolsheviks portrayed the rebellion as a White Guard conspiracy directed from abroad and had it bloodily suppressed by the Red Army. In an unprecedented criminal court, hundreds of Kronstadt sailors were shot on the spot, over 2000 were sentenced to death, thousands received prison sentences or were sent to the newly established camps in Cholmogory or on the Solovetsky Islands. 2500 civilians from Kronstadt were exiled to Siberia.

At the end of the Civil War, the Bolsheviks had succeeded in regaining most of the secessionist territories. By 1922, they controlled 96% of the territories of the Russian Empire. In December 1922, a new state was founded on this territory, which was to leave its mark on the 20th century as a superpower: the Soviet Union.

Oath-taking by Red Army soldiers, 1919

Russian and German soldiers celebrate the end of the war on the Eastern Front (1918)

Search within the encyclopedia