Oath

![]()

This article explains the legal term oath, for other meanings see Oath (disambiguation).

![]()

The articles oath, swearing, oath formula and oath overlap thematically. Information you are looking for here may also be found in the other articles.

You are welcome to participate in the relevant redundancy discussion or to help directly to merge the articles or to better distinguish them from one another (→ Instructions).

The oath (also called bodily oath) serves the personal affirmation of a statement.

It obliges to tell the truth (e.g. in court proceedings) and to bear the consequences (e.g. in the oath of allegiance) of the oath. The oath is often referred to as a conditional self-cursing, since in an oath with a religious affirmation a deity is invoked as an oath-taker and as an avenger of untruth. Oaths exist not only in the European legal tradition (e.g., among the Greeks, Romans, and Celts), but also in China, ancient Israel, and among numerous ethnologically studied indigenous peoples. The ancient Greek oath of Hippocrates obliged physicians to observe their professional duties and ethical principles (including protecting the sick from harm, observing the duty of confidentiality).

An oath is usually associated with rituals or ceremonial acts intended to express universal awareness of the efficacy of a statement or promise of conduct made under oath. For example, all present or all participants must rise. Culturally different, for example, the left hand is placed on a constitution or a religious scripture and the right hand is shown openly or as an oath hand. Such actions are only in a few cases also standardized in writing, but mostly only traditional consensus.

There was also the superstition that one could at least protect oneself from the "punishment of God" for perjury and that the oath binding would be cancelled, provided that a counter-ceremony, e.g. the crossing of the fingers of the left hand, was performed covertly.

Senator Barack Obama taking the oath of office for the first time as the 44th President of the United States. Obama, like Chief Justice John Roberts, made a few slips of the tongue. To be on the safe side, the oath was repeated on 22 January 2009, this time without a Bible.

History

Ancient Near East

In the ancient Near East, oaths were important in state treaties. Usually a number of gods were invoked to punish the oath-breakers. In the vassal treaty between Asarhaddon and the kings of the Medes, for example, the oath-breakers shall not live to a ripe old age, An shall strike them with sleeplessness, affliction, and disease, Sin shall strike them with leprosy, Šamaš shall blind them, Ninurta shall strike them down with his arrows, their blood shall fill the steppe, a stranger shall possess the womb of their wives, their sons shall not inherit them, and Adad, the dike-count of heaven, shall flood their land. Išḫara, an underworld deity, protected the oath (in the Šuppiluliuma-Šattiwazza treaty, KBo I, nos. 1 and 2, she is specifically named in the curse formula as "mistress of the oath"). In Persia Mithra was the protector of the oath and of justice.

Ancient

In the OT God swears by Himself (Gen 22:16-17 EU) to Abraham to bless his lineage and multiply it like the stars in the sky. In the OT, God calls on people (Deut 19:12 EU) not to swear falsely by His name and (Deut 30:3 EU) after an oath not to break the word, but to do everything as it passed their lips when they swore.

According to Prodi, an innovative element consists in the involvement of the God of the Jews his oath to covenant with Israel, while in other ancient cultures the gods act only as witnesses and avengers (-innen, cf. Erinnyes) of the oath. The biblical term covenant renders the two key biblical terms ברית (Hebrew berīt) and διαθήκη (Greek diathēkē) and includes the meanings of a solemn covenant, treaty, or oath, diathēkē otherwise standing for testament. The (Christian) choice of words New and Old Testament for the main parts of the Bible also go back to this. The Christian theology emphasizes the declaration of God's will, the Jewish interpretation goes rather in the direction of contract or covenant.

In the Old Testament the execution of the oath on the hips of the oath taker points to a usage that was also common among the Romans. They swore by the testis, the (own) testicles - the word relationship of witness, testify and procreation has a similar connection.

Christianity

In the New Testament, Jesus demands in the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5:33-37 EU) not to swear at all, but to keep his word even without an affirmation by oath. Whether Christians may swear an oath was therefore often disputed in church history. Some church fathers of late antiquity rejected the oath altogether; but canon law, which was authoritative for later Catholic doctrine, permitted it and held that it was reasonable for everyone to take. The larger Protestant churches also approve of the oath, while conservative Anabaptist groups, such as the Amish, Old Order Mennonites, Old Colony Mennonites, Hutterites, and Quakers, reject it to this day, citing the Sermon on the Mount.

The prohibition of oaths is also taken into account in the Catholic Church, for example, with the ritual of the vow. This is understood as the thoughtful and freely offered promise to God. This happens with religious vows, which are taken by an ecclesiastical minister (for instance by the bishop or superior) in the name of the church, like private vows. The discussion of the different roles and influences as well as the question of the oath as a political sacrament played an important role in the investiture controversy or the attribution of marriage. The also superordinate community-creating element as well as the Christian scepticism towards the oath led to important differentiations. According to Paolo Prodi's classic, it was the Christian Church itself that, as guarantor of the oath, paved the way for the secularization of politics.

Since David Hume questioned the derivability of an ought from a being (cf. Hume's Law), John Searle made the proposal to derive an ought from a being by means of a promise. This corresponds to the idea of contractual fidelity (cf. Pacta sunt servanda), which is why an oath can be understood as a kind of contract in which the ultimate judge of the fulfilment of the contract can be seen as the one to whom the oath refers (e.g. an oath to God).

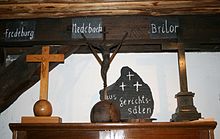

Crosses of oaths in the Bad Fredeburg court museum

Role of different legal cultures

In the early Middle Ages of continental Europe, the oath took up ancient as well as Judeo-Christian traditions; elements of Germanic legal customs were also adopted, as in the Ordalia (judgment by God), and were only replaced by the oath in modern form in a laborious process. The oath also plays an important role in the Anglo-Saxon legal tradition of common law that developed at that time, which emphasizes the right of judges and oral proceedings. It plays a different role depending on the legal circle. In the Anglo-Saxon environment, among other things, an oath was already taken from juvenile freemen not to commit crimes. Up to the present day, cross-examination under oath is part of the administration of justice and, because of its dramaturgical value, also a popular subject of court films.

Oaths were already widespread in Germanic legal culture and served as a means of orally determining the law. In the case of the sumbel (an. sumbl, aeng. symbel, as. sumbal), the oath was administered in the context of a ritual drink or a ritual drinking party. Examples can be found in the Beowulf epic (lines 489-675 and 1491-1500) in the Old Saxon Heliand, as well as in the Edda song Lokasenna, the Heimskringla, in the account of Sven Gabelbart's funeral toast for his father, and in the book about the Norwegian kings, the Fagrskinna. This involved swearing by the chieftain's horn circling during a toast, occasionally including animals.

Germanic oaths were also a popular topic of research as early as the 18th and 19th centuries. They were also used in the völkisch and National Socialist environment to differentiate from Christian-Jewish antiquity and the independent German legal culture. Among other things, the oath formula and the required touching of an object was the subject of discussion. Corresponding rituals, such as the oath of allegiance or public swearing-in and vows in the military, were thus traced back to an early, pre-Christian and Germanic origin.

Prodi now sees the decisive turn in the 5th to 7th centuries, where at councils the pagan oath and the oath made per creaturas were forbidden, while the Christian oath remained and acquired a more clearly sacred and liturgical meaning. These thus found their way into the first penitential books and pontificals. The Vœux du paon, a courtly verse poem (c. 1312) in which jocular oaths to a peacock advance to a courtly social game, is a later reflex of this pagan ritual. At the pheasant festival in Lille in 1454, among other things, a pheasant was sworn at the Burgundian court to undertake a crusade, which, however, did not come about.

Belton and Lupoi see a shift of the oath of the Roman period from the political and legal sphere into broad social spheres as a common phenomenon of (early medieval) European jurisprudence.

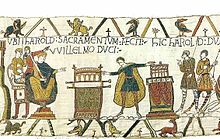

Harold's perjury in the representation of the Bayeux Tapestry (11th century). Witnesses to the scene note the perjury, it goes unnoticed by the king. The carrying sticks of the reliquary point to the Ark of the Covenant.

The peacock game or Voeux du Payon, in which each person present makes an oath (or vow, both documented) to a roasted peacock.

Sven Gabelbart burying his father Harald, 19th century depiction; in the middle an expiatory boar, not mentioned in the report on Gabelbart, but in the Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar.

Harold swears the oath of allegiance to the later William the Conqueror before his throne on a reliquary. Depicted in the 19th c. The forced oath was broken, which is also indicated by the hand posture.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is an oath?

A: An oath is a promise that is spoken out loud in front of witnesses.

Q: How can a person who cannot speak make an oath?

A: A person who cannot speak can make a sign that they are "taking an oath."

Q: What is another way of saying "taking an oath?"

A: Another way of saying "taking an oath" is to say that they are "swearing an oath."

Q: How do people show that an oath is important to them?

A: When a person swears an oath, they often show that the oath is very important to them by calling God to see and remember the promise, and to show that the promise is true and cannot be taken back later.

Q: What are some objects that people use when taking an oath?

A: When a person takes an oath, they sometimes raise their right hand or put their hand on their heart, on the Bible, or on another holy book.

Q: In what situations are oaths used?

A: Oaths are used in many situations when a person needs to be true to what they say.

Q: Can a person promise without taking an oath?

A: Yes, a person can say "I promise that I will do this..." without taking an oath, but an oath is often seen as more formal and binding.

Search within the encyclopedia