North America

North America

.svg.png)

![]()

North America is the northern part of the American double continent. To the north lies the Arctic Ocean, to the east the Atlantic Ocean, to the south the Caribbean Sea and to the west the Pacific Ocean. North America is the third largest continent on earth after Asia and Africa and covers an area of 24,930,000 km² including Greenland, the Central American land bridge and the Caribbean. From a geological point of view, part of Iceland and eastern Siberia up to the Chersky Mountains also belong to North America.

North America has a population of around 529 million and is the most urbanized part of the world (81 percent), with Mexico City, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago and Toronto among the largest metropolitan areas.

South America and North America were named after Amerigo Vespucci. He was the first to realize that the land that Christopher Columbus discovered and considered India was a separate continent. Connecting North and South America is the isthmus of Panama. Occasionally Central America is mentioned as a separate continent, but the prevailing opinion is that it is a region such as Western Europe and belongs to North America.

The Pan-Indian name for North America is "Turtle Island". The term originates from the Algonquin and Iroquois languages and goes back to similar creation myths in which the primeval continent came into being on the back of a turtle. Then, as now, the term is closely associated with the spiritual ties of North American Indians to their homeland.

Geography

Nature area

North America includes Greenland, which is autonomously part of Denmark, Canada, the USA, Mexico, Central America and several Caribbean island states.

Almost the entire area of North America is located on the North American Plate, a part lies on the Pacific Plate. This is mainly the Lower California Peninsula in Mexico and the coastal strip of California from San Diego to north of San Francisco. The break between the Pacific and North American plates is called the San Andreas Fault. Both plates are steadily drifting northward, the Pacific plate at a faster rate. This causes the two plates to slide past each other. Since this does not happen smoothly, both plates get caught in different places and earthquakes occur in the area.

In the western part are the Alaska Range, the Rocky Mountains, the Western Cordillera and the Sierra Madre Occidental, which were formed mainly by the pressure of the Pacific Plate on the North American Plate about 80 million years ago. The highest peak in North America is Denali (Mount McKinley, 6190 m), located in the Alaska Range. In the north, Greenland with its inland ice and further south between Canada and the USA the Great Lakes are worth mentioning, which are legacies of the last ice age. Here is the second largest lake in the world after the Caspian Sea, Lake Superior, with an area of about 82,000 square kilometres. On the eastern side are the Appalachian Mountains, which are among the older mountains in the world, dating back some 400 million years. Between the Appalachians and the Rocky Mountains are the Great Plains, a central lowland plain through which the Missouri River and the Mississippi River flow. The Mississippi Valley is also called Tornado Alley because of the tornadoes that occur here.

Since 1931, Rugby, North Dakota has been considered the geographic center of North America. The position was marked with a 4.5 m high stone obelisk.

Geology

North and South America are geologically distinct continents and were joined relatively late at the Central American land bridge. In earlier Earth history, North America was part of the primordial continent Laurasia, while South America (with Africa and India) was part of Gondwana.

In the course of continental drift, the Atlantic Ocean opened so that North America was separated from Europe. The same happened with South America and Africa. The long, north-south running mountain ranges of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes are a consequence of this drift and are not found in such a pronounced form on any other continent.

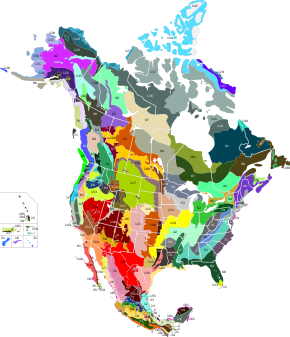

An overview of the distribution of the most important rock types is given in the figures below.

·

Magmatic rocks (plutonites)

·

Magmatic rocks (vulcanites)

·

Sedimentary rock

·

metamorphic rocks

NASA satellite image, ca. 2002

Geological map of North America

Climate

Classification

Due to its large north-south extension, the climate of the North American continent is characterized by strong contrasts. In the area of the northern Canadian islands and Hudson Bay, a polar tundra climate prevails, which is bordered to the south and west by the boreal zone. The Hudson Bay as "America's icebox" and the cold Labrador Current on the Atlantic coast cause an extension of the polar climate to the south on the east coast of the continent. This polar zone is joined in the south by temperate climates, which, however, are mainly located on the territory of the USA. These are the central continental steppes and prairies, and the humid continental climates in the northeast, which change southward to desert climates in the southwest and humid subtropical climates in the southeast, respectively. For the Cordillera region, a high mountain climate is characteristic in large parts. It has a decisive influence on the climatic condition of the surrounding areas. While on its windward side in the west an oceanic climate with intensive rainfall in winter and dry, cool summers (southwestern Canada and northwestern USA) or a Mediterranean to desert-like climate (California and southern California) prevails, on the leeward side it causes an arid climate due to its function as a precipitation bar and thus favors a dry-hot desert climate in the southwestern states of the USA.

Temperature

A rough overview of the course of the isotherms in North America shows the following: In the center of the continent, the average temperature rises relatively uniformly from north to south, as might be expected. Deviations from this pattern result from topographical features, such as Hudson Bay or the Great Lakes. The large temperature amplitudes caused by the continental climate are typically pronounced and reach up to 45 K in northern Canada. On the Pacific coast, the maritime influence prevents such extreme differences in the course of the year and the annual amplitudes drop to low double-digit values, such as in Vancouver with 14.2 K, down to single-digit values in San Francisco with 7.6 K.

On the east coast of the continent, however, with the exception of Florida, the picture is completely different. Here, the annual cycle of temperatures is characterized continental despite the proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. This is due on the one hand to the cold Labrador Current, which provides very low winter temperatures up to 35° N, and on the other hand to the location of the North American continent in the west wind zone, which also leads to quasi-continental conditions on the east coast.

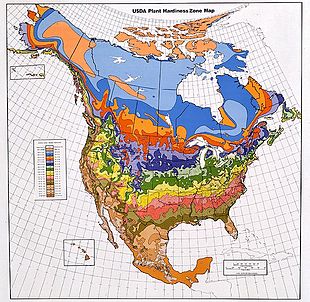

See also: USDA climate zones

Precipitation

The strong oceanic influence ensures very high precipitation in the west on the Pacific coast with a summer maximum. The areas with the highest precipitation are to be found on the windward side of the British Columbia Cordillera, while precipitation decreases significantly towards the south and reaches its relative minimum in the semi-arid climate of southern California. Within the Cordillera, precipitation distribution is strongly influenced by regional topography, yet a clear gradient from windward to leeward is evident here as well. The western part of the continent outside the Cordillera region is relatively poor in precipitation, ranging from arid regions in the southwestern states of the USA to the semi-arid steppes and the continental boreal zone in Canada with a maximum of 500 mm annual precipitation. In the east, the maritime influence is clearly noticeable. Relatively high annual totals are recorded along the entire east coast of the North American continent, with intensity increasing from north to south. Especially along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, annual totals well above 1000 mm are common. The tropical maritime air masses that trigger this precipitation affect the precipitation intensity of the entire southeastern United States. In the area of the Great Lakes there is also a maritime influence, the lake effect, due to their size.

Air masses and wind systems

The weather pattern of the North American continent is influenced by several factors. On the one hand, its location in the area of the westerly wind zone is significant, the main axis of which runs roughly along the 48th parallel and reaches high altitudes. Due to the barrier effect of the Cordilleras, these air masses are fed to the Aleutian low in the north and the Pacific high in the south. On the eastern side of the continent, the weather pattern is influenced by the Icelandic low and the Azores high. Also of great importance is the geomorphology of the continent. The absence of a mountain barrier in the west-east direction allows an unhindered meridional exchange of air masses. When the tropical-warm and polar-cold air masses with different humidity levels meet, cyclones are formed which move across the continent from west to east following the influence of the westerly winds. The unhindered meeting of these opposing air masses is also the most important prerequisite for most extreme climatic events and is the reason for the great danger to the North American continent from so-called climatic hazards.

Climate extremes

→ Main article: Climate extremes in North America

The aforementioned topographical structure with the Rocky Mountains along the west coast and the Appalachian Mountains on the east coast, which funnel the continent southwards, as well as the adjacent Pacific Ocean in the west, the Atlantic Ocean in the east and the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico in the south, cause the large-scale and frequent occurrence of extreme weather events, which also makes the North American continent appear in this respect as a "land of unlimited possibilities". The occurrence of these climatic hazards is concentrated primarily on the continental territory of the United States of America and only in exceptional cases also affects southern Canada and, in the case of hurricanes, the entire Caribbean region and Central America. All extreme events are seasonal in nature, but vary greatly in terms of their distribution area or the size of the region affected. Thus, tornadoes in the central United States and teleconnections of El Niño events occur in spring, sultriness and heat waves, drought and heavy rain in summer, hurricanes in late summer and autumn, and blizzards, snowfalls and frosts in winter.

The damage caused by these climatically induced events in the USA varies greatly from year to year, averaging US$ 10.47 billion per year between 1975 and 1998. In addition, climatic hazards claimed about 8200 lives over the entire period. In addition, however, there are spectacular individual events which are not included in the above-mentioned period and which can exceed the long-term average many times over. These include, for example, the Tri-State tornado of 18 March 1925, which claimed the lives of 695 people, the Johnstown Flash Flood, which claimed around 2,200 victims in the state of Pennsylvania in May 1889, and, the most recent example, Hurricane Katrina, which set completely new standards in this respect, claiming 1833 lives and causing financial losses of over US$ 100bn. However, the calculation of damage is subject to many uncertainties, and estimates often differ significantly, especially with regard to financial damage. This is particularly true if, in addition to the direct damage caused by actual destruction, the indirect and economic damage is also taken into account. In this context, large-scale events such as droughts, floods and hurricanes are more difficult to analyse in terms of damage than smaller-scale events such as tornadoes or flash floods. There are also significant discrepancies in determining the number of casualties for large-scale events. Cold snaps and heat waves are particularly worthy of mention here, where the distinction between direct victims and natural fatalities requires complicated statistical calculations. In principle, however, it can be stated that flooding is the most damaging consequence of climate extremes, followed by hurricanes and tornadoes. What is surprising, however, is that in the period from 1975 to 1998, for example, the second most dangerous weather event for life and limb was lightning strikes.

Hardiness zones of North America (extreme minimum temperature)

Hurricane "Katrina" over the Gulf of Mexico, August 28, 2005

The terrestrial ecological regions of North America (detailed legend to the colours in the map description)

Search within the encyclopedia