Atlantis

![]()

This article is about the island kingdom of Atlantis described by Plato. For other uses of this name, see Atlantis (disambiguation).

Atlantis (Ancient Greek Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος Atlantìs nḗsos 'Island of Atlas') is a mythical island empire first mentioned and described by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428/427 to 348/347 BC) in the mid-4th century BC. It was, according to Plato, a maritime power that subjugated large parts of Europe and Africa starting from its main island located "beyond the Pillars of Heracles". After a failed attack on Athens, Atlantis had finally perished around 9600 BC as a result of a natural disaster within "a single day and an unfortunate night".

Atlantis is a story embedded in Plato's work, which - like the other myths of Plato - is supposed to illustrate a previously established theory. The background of this story is controversial. While ancient historians and philologists almost without exception assume an invention of Plato inspired by contemporary models, some authors suspect a real background of the story and made countless attempts to localize Atlantis (see the article Localization hypotheses on Atlantis).

The possible existence of Atlantis was already discussed in antiquity. While authors such as Pliny denied that the island kingdom in question existed, others, for example Krantor, Poseidonios or Strabon, considered its existence conceivable. The first parodies of the subject also emerged in antiquity.

In the Latin Middle Ages, the myth of Atlantis was more or less forgotten, until it was finally rediscovered and disseminated in the Renaissance, as scholars in Europe now understood Greek again. Plato's descriptions inspired the utopian works of various early modern authors, such as Francis Bacon's Nova Atlantis. The literary motif of the Atlantis myth is still used today in literature and film (see the article Atlantis as a subject).

A painted map of Atlantis from Athanasius Kircher's Mundus Subterraneus of 1665

Description of Plato

Plato describes the island of Atlantis in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written around 360 BC. The Critias remained unfinished. In these works the author lets the two politicians Kritias and Hermokrates as well as the philosophers Sokrates and Timaios meet and discuss. Even though these are historical persons (although only the first three are attested), the conversations attributed to them by Plato are fictional. The Socratic dialogue is used here as a rhetorical figure and is intended to convincingly convey Plato's doctrinal statements by developing them dialectically before the reader's eyes rather than dogmatically prescribing them. While the topic of Atlantis is only briefly touched upon in the Timaeus, a detailed description of the island kingdom follows in the Critias.

The two Atlantis dialogues Timaeus and Critias are only parts of an initially apparently more extensive plan. The dialogue Timaeus immediately follows the dialogue Politeia, whose results it recapitulates. The short Critias breaks off unfinished, and Plato did not even produce the dialogue of Hermocrates announced in the Timaeus. Plutarch gave as a reason for this that Plato had died before completing his work because of his advanced age. The last dialogue in this series is the Nomoi, in which the end of the last natural catastrophe in the sense of Timaeus and Critias is chosen as the starting point for the discussion.

Origin of the Atlantis lore

The presentation of the main features of the Platonic ideal state of the Politeia in the first part of the Timaeus is followed by a wish expressed by Socrates to see the advantages of such a city-state in reality and especially to examine its probation in case of war (Tim. 17a-20c). Critias then reproduces a story which he states his grandfather had told him in his youth (Tim. 20d ff.). The grandfather in turn had heard it from the famous lawgiver Solon, with whom his father Dropides ("Dropides II") had been a friend. Solon had brought the news of Atlantis from Egypt, where he had heard it in Sais from a priest of the goddess Neith (Tim. 23e). This priest had translated the information from "sacred writings". In several places of the story Plato lets Kritias emphasize that his story was not invented, but actually happened (Tim. 20d, 21d, 26e).

Frame story of the Atlantis lore

The content of the story recalled by Critias is one of the supposedly "greatest heroic deeds of Athens", namely the defense against a huge army of the expansive sea power Atlantis. That island empire, which like Athens had existed 1000 years before the founding of Egypt (Timaeus 23d-e), is said to have dominated many islands and parts of the mainland, Europe as far as Tyrrhenia and Libya (North Africa) as far as Egypt, and was about to subjugate Greece as well (Timaeus 25a-b). After the Athenians, who were outstanding in courage and the arts of war, had repelled the attack, first as the leading state of the Hellenes, then fighting alone after the others had fallen away, the "whole warlike race" of the Atlanteans died to a large extent during one day and one night due to heavy earthquakes and floods, and Atlantis sank into the sea due to earth tremors (Timaeus 25c-d; Critias 108e). Only Egypt, which had been founded 8000 years before Solon and from where the tradition of Athens' heroic deed originated (Timaeus 23d-e; Critias 108e, 109d ff., 113a), was spared.

Atlantis

In the Critias Plato describes Atlantis in detail: It had been an empire larger than Libya (Λιβύη) and Asia (Ασία) combined (Timaeus 24e). In Plato's time these terms were understood to mean North Africa without Egypt and the then known parts of the Near East. The main island lay outside the "Pillars of Heracles" in the Atlantìs thálassa, as Herodotus already calls the Atlantic Ocean (Herodotus I 202,4). According to Plato, the "Island of Atlas" was rich in raw materials of all kinds, especially in gold, silver and "oriharukon", a "metal" first mentioned in the epyllion "Shield of Heracles" attributed to Hesiod, which Plato describes as "shimmering with fire" (Kritias 114e). Further, Plato mentions various trees, plants, fruits, and animals, including the "largest and most voracious animal of all," the elephant (Critias 115a). The vast plains of the great islands had been extremely fertile, precisely parcelled out and supplied with sufficient water by artificial canals. By utilizing the rain in winter and the water from the canals in summer, two harvests a year were possible (Critias 118c-e).

The center of the main island formed a plane of 3000 by 2000 stadiums. A Greek "stadium" is about 180 meters, an Egyptian "stadium" is about 211 meters, therefore it is in the order of 400 to 600 kilometers. This plain was surrounded and traversed by canals laid out at right angles, resulting in a multitude of small inland islands. The acropolis of the capital was five stadia wide and built on a mountain that was centrally located on the island. Around this acropolis were three ring-shaped canals, connected to the sea by a wide channel. The inner artificial water belt had a width of one stadium, followed by two pairs of concentric land and water belts, each two and three stadia wide (Critias 115d-116a). The outer two channels Plato describes as navigable.

In the center of Atlantis, according to the dialogues, there was a temple of Poseidon on the Acropolis, which Plato described as "a stadium long, three plethra (that is about 90 m) wide, and of a corresponding height" and covered inside and out with gold, silver, and oriharukon. Around the temple stood golden votive statues. One cult image showed the sea-god as the driver of a six-horse chariot (Kritias 116d-e). Near the central complex was a hippodrome. The dwellings of the rulers were also located in the innermost district, which was enclosed by a wall. The ring-shaped outlying districts of the city housed, from the inside out, the quarters of the guards, the warriors, and the citizens. The entire complex was enclosed by three further ring walls arranged concentrically (Critias 116a-c). The two outermost canals were laid out as harbours, the one further inwards serving as a war port and the outer one as a trading port (Critias 117d-e).

Poseidon had given power over the island to his son Atlas, begotten with the mortal Cleito, who was the eldest of his descendants from five sets of twins (Critias 114a-c). Atlas and his descendants ruled the capital, and the lines of his younger brothers ruled the other parts of the empire. Over time, Atlantis was transformed from an originally rural island into a powerful naval power through ever-expanding construction and upgrades. The descendants of Atlas and his siblings had a unique army and a strong navy with 1200 warships and 240,000 crew for the fleet of the capital alone (Kritias 119a-b). With this force they subdued Europe as far as Tyrrhenia and North Africa as far as Egypt (Timaeus 24e-25b). Only the Athenians, who were far outnumbered, could bring this advance to a halt.

This military defeat of Atlantis is presented as a punishment of the gods for the hubris of its rulers (Timaeus 24e; Critias 120e, 121c). Because the "divine portion" of the Atlantids had visibly diminished through their mixture with humans, they had been seized by greed for power and wealth (Kritias 121a-c). The "Critias" breaks off before the gods assemble for a judgment on the empire, at which further punishments were to be discussed: "But the god of the gods, Zeus, who rules according to the laws and is well able to recognize such things, decided, when he saw a noble race (so) shamefully descend, to inflict punishment on them for it, (121c) so that they, brought to their senses by it, might return to a nobler way of life. He therefore summoned all the gods together to their most venerable abode, which is in the midst of the universe, and affords a survey of all things that have ever been made partakers of becoming; and having summoned them together, he said ...."

Primeval Athens

Next to Atlantis Plato describes in the Critias the "Ur-Athens", although much shorter. In contrast to the real Athens of Plato's lifetime, ancient Athens is a pure land power that dominated Attica as far as the Isthmus of Corinth (Critias 110e). Although located near the coast, it had no harbors and did not engage in seafaring by deliberate choice. Plato's polis Athens is described as an extremely fertile land, covered with fields and forests, and "capable of supporting a large army freed from the business of agriculture" (Critias 110e-111d). The goddess Athena herself had endowed the political structures and institutions in the city-state named after her, which Plato presents as nearly identical to those of his ideal state described in the Politeia. When Athens was attacked by Atlantis, she was able to repel the invaders and even liberated some already subjugated Greek tribes. As a reason why no records, stories or legends of the glorious victory over the Atlanteans exist in ancient Greece, Plato cites earthquakes and floods that repeatedly afflicted the ancient Hellenic tribes. But Plato also mentions a very great and particularly devastating flood that resulted in the downfall of the ruling upper class on the coasts. It left behind only a small portion of illiterate peasants who lived in the mountainous regions. As a result, the complete knowledge that the Greeks had acquired up to that point was lost.

Plato (left) and Aristotle - Detail from "The School of Athens" by Raphael (1509)

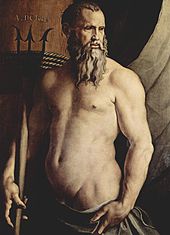

Poseidon - painting by Bronzino (1503-1572)

See also

- Atlantis as a subject (in art and culture)

- Localization hypotheses about Atlantis

Search within the encyclopedia