New Deal

![]()

This article is about the American economic and social reforms from 1933 to 1938. For the social program in the United Kingdom conceived in 1998, see New Deal (United Kingdom).

The New Deal (AE: [nuː diːl]) was a series of economic and social reforms enforced between 1933 and 1938 under U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to the Great Depression. It represents a major upheaval in the economic, social, and political history of the United States. The numerous measures have been divided by historians into those intended to alleviate hardship in the short term (relief), those intended to stimulate the economy (recovery), and those intended for the long term (reform). Relief included aid for the many unemployed and poor, recovery included changes in monetary policy, and reform included, for example, the regulation of financial markets and the introduction of social insurance.

The question of how successful the New Deal was is still disputed today. The desolate state of the American economy was overcome, but on the other hand full employment was not achieved until 1941. The Social Security Act of 1935 laid the foundation of the American welfare state, but social security for all and an "equitable" distribution of income and wealth were not achieved. It is undisputed that the state's massive intervention policy gave new hope to a discouraged and disoriented nation. Unlike the German Reich and many other countries, democracy was preserved in the United States during the Great Depression. The market economy was saved by creating a more stable economic order, primarily through regulation of the banking system and securities trading.

Since the New Deal, liberalism in the United States has been associated with pro-worker policies rather than the defense of corporate freedom. Since the 1960s, "liberals" have been those citizens and politicians who invoke the New Deal tradition, pursue pro-worker policies, and advocate the expansion of civil liberties.

New Deal is a figure of speech in the English language meaning "redistribution of the cards". Roosevelt initially used the phrase in the 1932 presidential campaign only as a suggestive slogan. New Deal subsequently became accepted as a term to describe economic and social reforms.

A school feeding program to combat child malnutrition was one of the measures taken to alleviate the need.

Prehistory (1929-1933)

financial and economic crisis

Beginning with the stock market crash of 1929 (Black Thursday), the Great Depression developed, reaching its peak in 1932/33. Along with the German Reich, the United States was one of the countries hardest hit. From 1929 to 1933, the gross domestic product had almost halved. As a result of the financial crisis, 40% of the banks (9,490 out of an original 23,697 banks) had to be liquidated due to insolvency. The agricultural sector was also in crisis, with a large number of farmers unable to pay interest on loans. In addition, from 1930 to 1938, the Great Plains were hit by the Dust Bowl period, in which many villages and farms were buried under dust. As a result of the Dust Bowl, 2.5 million people had to abandon their farms.

The unemployment rate rose from 3% in 1929 to 24.9% in 1933. Many firms tried to avoid layoffs by cutting working hours. In 1931, one in three workers had to make do with part-time work under heavy wage cuts. At that time, there was no social safety net in the United States, especially no public unemployment insurance and no public pension insurance. Some employers and unions did have private unemployment insurance for their workers, but this coverage covered less than 1% of workers and employees. There was also no deposit insurance fund yet. When thousands of banks went bankrupt, many citizens lost all their savings.

Because states and cities were legally required to balance their budgets each year, they responded to the sharp increase in welfare needs during the crisis mostly by lowering welfare levels so that welfare was provided only to the poorest of the poor. In 1932, only a quarter of all unemployed people and their families received state assistance. In most cities, social assistance was based on the physical subsistence level; in Philadelphia, for example, assistance had to be cut to a level that could buy only two-thirds of the food needed to maintain health. Despite a considerable overproduction of food, famine prevailed in many parts of the country, and there were occasional deaths from starvation. Slums sprang up in many cities, dubbed Hooverville after the incumbent president.

Reaction of the Hoover government

President Herbert Hoover, as a libertarian, advocated the greatest possible government restraint in regulating the economy and relied on the principle of self-help by citizens. He initially hoped that the crisis would end on its own. Beginning in October 1930, he attempted to alleviate the situation of the unemployed and their families by establishing private relief organizations. The President's Emergency Committee for Employment and its successor, the President's Organization on Unemployment Relief, collected private donations that were distributed to the needy. While the organizations succeeded in increasing the amount of private donations, these sums were far from sufficient as a means of alleviating need.

After the crisis worsened considerably in its third year (1931), Hoover changed strategy and opened a period of experimentation to look for possible solutions. In the presidential campaign of 1932, he declared the restoration of confidence in the country's economic strength to be the greatest problem. This would most certainly be restored if the state could once again present a balanced budget. The Revenue Act of 1932 brought a significant tax increase. This was Hoover's way of ensuring that the state would no longer have to borrow money and thus would no longer have to compete with private individuals who were desperate for loans. While maintaining the doctrine of government non-interference in the economy, he attempted to encourage businesses to undertake private initiatives to combat the recession (voluntarism). However, such initiatives, such as the National Credit Association, designed to prop up weak banks, failed. Based on these experiences, Hoover came to the realization in his last year in office that voluntary solutions were not enough. With the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, he finally made bank bailouts a government function. He prevented Robert F. Wagner's successful bill in Congress to introduce public unemployment insurance by vetoing it as president. Reluctantly, he signed into law a compromise bill passed by Congress that created $1.5 billion in job creation programs. The money was used, among other things, to build Hoover Dam.

Roosevelt's election campaign (1932).

Franklin D. Roosevelt's political program remained fuzzy and unclear during the campaign, but his general stance was widely known. Like his cousin Theodore Roosevelt, who had been President of the United States from 1901 to 1909, he was a progressive. In his view, government should intervene wherever it was necessary in the public interest. His aspiration was to ensure a minimum level of economic security for the middle and lower classes of society, a security that was taken for granted by the upper classes, to which Roosevelt belonged by birth as a "patrician." As governor of New York, he had been one of the first to respond to the Depression with a spirited emergency program, creating public work programs. This enabled him to present himself in the election campaign as a clear alternative to Hoover.

During his nomination speech in 1932, he spoke of a "New Deal" for the first time:

"Throughout the nation men and women, forgotten in the political philosophy of the Government, look to us here for guidance and for more equitable opportunity to share in the distribution of national wealth.... I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people. This is more than a political campaign. It is a call to arms."

"From across the nation, men and women who have been forgotten by the political philosophy of government look to us for leadership and a fairer chance at a share of the national prosperity. I commit myself to a redistribution of the cards for the American people. This is more than a political campaign. This is a call to arms."

- –

Like Hoover, he did not want to give up the goal of a balanced budget. He advocated raising taxes significantly so that the subsistence level of every citizen could be secured. He believed that the deeper problem lay in too unequal a distribution of purchasing power - coupled with an excess of speculative investment.

"Do what we may to inject life into our ailing economic order, we cannot make it endure for long unless we bring about a wiser, more equitable distribution of national income ... the reward for a day's work will have to be greater, on average, than it has been, and the reward for capital, especially capital that is speculative, will have to be less."

"Whatever we do to breathe life into our ailing economic order, we cannot do so in the longer term until we achieve a more meaningful, less unequal distribution of national income... the reward for labor someday must be higher - on average - than it is now, and the gain from wealth, especially speculatively invested wealth, must be lower."

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

On July 2, 1932, the day he was nominated as the Democratic presidential candidate, Roosevelt promised a "new deal for the American people," a term that later came to be used to describe the reforms he implemented.

The Brain Trust

During the 1932 election campaign, Roosevelt first introduced his Brain Trust. It was an open-ended group of economic and legal experts who would advise Roosevelt. Founding members were professor of law Raymond Moley, economist Rexford Tugwell, professor of law Adolf Augustus Berle, Justice Samuel Rosenman, lawyer Basil O'Connor, and General Hugh S. Johnson. These advisors did not agree on all issues, but there was consensus on the basic direction of the policy recommendations. First, they assumed that both the causes of the Depression and the remedies for it were to be found in the United States itself. In this they differed from the Hoover administration, which saw the causes in Europe and part of the solution in protectionism. Tugwell explained the cause of the Great Depression in terms of the underconsumption theory by saying that wage growth in the 1920s had fallen short of productivity growth, so that there was insufficient demand for the goods produced. This analysis also influenced some of Roosevelt's speeches. Second, they were all progressives; they assumed that the concentration of economic power in large corporations required increased government regulation. Berle and Tugwell, in particular, had written extensively on competition law and antitrust in particular. For the later phase, the Second New Deal, Felix Frankfurter and Louis Brandeis, who were more in the tradition of anti-trust legislation to unbundle trusts, also became influential.

On February 22, 1933, Roosevelt asked Frances Perkins, a dedicated social politician, to take over the Department of Labor. She agreed on the condition that she be allowed to lobby for a ban on child labor, the creation of a pension scheme, and the introduction of minimum wages. Roosevelt agreed, but stressed that she could not expect very much help from him. She became the first female Secretary of State in the United States and was among the few Secretaries to serve more than three terms. With the support of Robert F. Wagner in particular, she succeeded against considerable opposition in laying the foundations of the American welfare state.

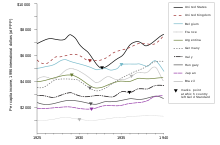

Development of per capita income in the United States in international comparison

Dust Bowl: A dust storm threatens the town of Stratford, Texas

Herbert Hoover (left) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (right) on the way to the Capitol for Roosevelt's inauguration, March 4, 1933

Unemployment in the United States since 1890

Development of the New Deal

Historians distinguish a first phase ("First New Deal" - 1933 to 1934) and a second phase ("Second New Deal" - 1935 to 1938). The "First New Deal" dealt with the most urgent economic and social problems of the crisis-ridden economy. The Second New Deal consisted mainly of longer-term measures.

Another common subdivision is the division into measures intended to make people's social situation more bearable in the short term (relief), those intended to bring about an economic recovery and measures intended to bring about a longer-term improvement through structural changes (reform).

First New Deal (1933-1934)

100-day program

After winning the 1932 presidential election, Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933. At that time, citizens feared that all attempts to overcome the crisis would fail because of the political system of the United States, in which any initiative is very much dependent on cooperation due to the American expression of checks and balances. At the time, the influential journalist Walter Lippmann saw the greatest danger not so much in Congress giving Roosevelt too much power as in denying him the support he needed. These fears were groundless, however. In a first special session of the 73rd Congress from March 9 to June 15, known as the "100-day program," Roosevelt succeeded in passing a number of basic bills. Because of the general yearning for an end to the crisis, Roosevelt was able to work through the 100-day program in an unprecedented climate of bipartisan approval. This gave U.S. citizens new confidence, and the United States rebounded from near collapse.

"At the end of February we were a congeries of disorderly panic-stricken mobs and factions. In the hundred days from March to June we became again an organized nation confident of our power to provide for our own security and to control our own destiny."

"At the end of February we were a hodgepodge of disorganized, panic-stricken rabble-rousers and splinter groups. In the 100 days from March to June, we again became an organized nation with the confidence to provide for our own security and control our own destiny by our own efforts."

- Walter Lippmann

Reform of the banking system

From 1929 onwards, the US financial system was destabilised by bank runs. These occurred because it became known that many banks had accumulated bad loans or had made heavy losses in investment banking. Fearing for their assets, many bank customers then tried to withdraw their bank deposits, which led to insolvency and bankruptcy of banks because they could not make longer-term invested money immediately available. Bank runs often occurred on the basis of rumours, so that even relatively healthy banks could fall victim to such a development. As more and more citizens hoarded their money at home as a precaution, the banks had less and less money available. This led to a credit crunch, which made it impossible in many cases to grant or extend personal and corporate loans. As a result, many private individuals and companies went bankrupt, which in turn aggravated the banking crisis and caused great damage to the real economy. The economic damage caused by the collapse of the banking system was a major reason for the extraordinary length and severity of the Great Depression. As a measure against bank runs, Hoover had already considered the Bank Holiday, but then discarded it because he feared it would cause a panic. Roosevelt, on the other hand, delivered an address over the radio, in the atmosphere of a fireside chat, explaining to the people in simple terms the causes of the banking crisis, what the government would do about it, and how the people could help. Just two days after Roosevelt took office, on March 6, 1933, all banks were ordered to close for four days (Bank Holiday). During this time, an assessment was made as to which banks could be saved by government lending and which would have to close for good. During this time, the Emergency Banking Bill was also passed, which placed banks under the supervision of the United States Department of the Treasury in the future. These measures succeeded in restoring citizens' confidence in the banking system in the short term: Immediately after the banks reopened, deposits increased by one billion dollars.

In addition to the bank runs, legislators saw the high exposure of many banks to volatile securities transactions, which had caused existence-threatening losses with the sudden drop in value in the course of the stock market crash of 1929, as further reasons for the banking crisis. Further, banks had made an unusually large number of risky loans in the 1920s. It was suspected that the high risk appetite of many banks was also due to the fact that these low-quality securities, especially loan notes with a high risk of default, could be sold to less well-informed bank customers. The legislator wanted to put a stop to the presumed conflict of interest within the banks, on the one hand to advise customers well and on the other hand to make as high a profit as possible with their own securities transactions. After the reopening of the banks, the Glass-Steagall Act was passed. This act introduced the separation banking system. Commercial banks were prohibited from risky securities transactions. The credit and deposit business of commercial banks, which was important for the real economy, was thus to be separated from risky securities transactions, which in future would be reserved for specialised investment banks. Furthermore, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was founded. This deposit insurance fund guaranteed bank customers a payout of their bank deposits in the event of the bankruptcy of a commercial bank. (Investment banks, on the other hand, were excluded from this government guarantee). These measures further strengthened confidence in the financial system. Subsequently, there were no more bank runs. The regulations also brought unprecedented stability to the American banking system: whereas even in the period before the Great Depression more than five hundred banks collapsed each year, after 1933 there were fewer than ten per year. The Glass-Steagall Act was repealed in 1999, but experienced a renaissance in the financial crisis beginning in 2007.

Financial market regulation

Before 1933, Wall Street traded securities about which no reliable information was available. Many companies refrained from publishing regular annual reports, or even published only selected data that tended to mislead investors. To stop the kind of wild speculation that had led to the stock market crash of 1929, the Securities Act of 1933 was enacted. This act required issuers of securities to release realistic information about their securities. In 1934, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was created, which has overseen U.S. securities transactions ever since. These measures strengthened the credibility of Wall Street.

Monetary policy

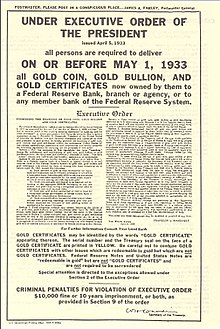

Due to the gold standard in place at the time, i.e. the pegging of the dollar to the price of gold, the Federal Reserve had to hold so much gold that every citizen could exchange their dollars for an equivalent amount of gold at any time. The FED should have pursued an expansionary monetary policy during the years of recession (1929-1933) to fight deflation and stabilize the banking system. However, because of gold automation, countercyclical monetary policy was not possible because a cut in the federal funds rate would have led to a relative decline in gold reserves. The FED had only the choice of letting deflation and the banking crisis run wild or abandoning the gold standard in favor of expansionary monetary policy, and chose the former. According to monetarist analysis of the 1960s, the contraction of the money supply deepened the recession, and the FED's response is now considered a serious mistake. However, this connection was insufficiently understood in the 1930s; the first criticisms of the effects of the gold standard came at the time from economists such as John Maynard Keynes. To end deflation and expand the money supply, the Roosevelt administration took measures that had already been used successfully in Europe. The export and private ownership of gold and silver were banned, larger gold holdings had to be sold to the FED for $20.67 per ounce (Executive Order 6102). The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 set the price of gold (well above the market price) at $35 per ounce. Since the ounce of gold now cost more dollars, the increase in the price of gold caused the dollar to depreciate to 59% of its last official value. The devaluation of the dollar caused foreigners to buy 15% more American goods, exports were thus encouraged (Beggar thy neighbour). These measures led to a de facto abandonment of the gold standard.

Measures against deflation

The idea of obliging entrepreneurs on a voluntary basis to refrain from unfair price undercutting and the dismissal of workers originally came from President Hoover. He wanted to fight deflation in this way. This idea was taken up by Roosevelt, but was to be implemented much more consistently. To this end, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) was founded in June 1933. It was headed by Hugh S. Johnson. In cooperation with representatives of the business community, the NRA drew up a code of conduct to which entrepreneurs could voluntarily commit themselves. This included the renunciation of unfair (price) competition, minimum prices, minimum wages, the recognition of trade unions, the introduction of the 40-hour week, etc. This catalogue of behaviour was intended to make negotiation more difficult. This catalogue of behaviour was intended to strengthen the bargaining power of trade unions and to control free-market competition. The ulterior motive was that this would stabilise prices and wages and consequently curb deflation. This was supposed to enable companies to hire workers again. However, the voluntary commitment was in fact not entirely voluntary. Participants in the program were allowed to advertise in their store windows and on their merchandise with the Blue Eagle. the symbol of the NRA. Businesses that could not advertise with this symbol ran the risk of being boycotted by customers. Also, many smaller companies complained that it was much easier for larger companies to pay the minimum wage. Shortly before the two-year program expired, the NRA was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1935 and was forced to cease operations.

Farmers' incomes had fallen steadily since the mid-1920s, by 60% between 1929 and 1933 alone. A number of relief measures had been conceived in Congress for some time, such as subsidizing exports. Herbert Hoover had suggested the formation of cooperatives to reduce capital and running costs; still others had proposed government purchase and destruction of food. Roosevelt wanted to stop the decline in prices in agriculture, similar to what he had done in industry. Aid was enacted for farmers who reduced their production. This was to stabilize the prices of agricultural products. The US government granted farmers funds for this purpose from the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of May 12, 1933. The originator of this idea was Rexford Tugwell, who argued that preventing overproduction was cheaper for the government than buying up and destroying surplus food at a later date. Prices soon stabilized. However, an undesirable side effect of the measure was that large landowners increased the productivity of their farms by terminating tenants. The AAA was also declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1936. Also, because the law was very popular with the rural population, the AAA was reformed and reauthorized regarding the Supreme Court's objections. It essentially still exists today.

Other aid for farmers

The Emergency Farm Mortgage Act was intended to alleviate the farm debt crisis. The Farm Credit Administration, established in 1933, organized debt restructuring into longer-term low-interest loans. The Resettlement Administration, established in 1935, organized the relocation of farmers, especially those from regions particularly affected by the Dust Bowl. It was replaced in 1937 by the Farm Security Administration, which provided aid to distressed farmers.

Social policy

In line with the attitude of most US citizens, the Roosevelt administration also believed that it was better for morale to provide unemployment benefits through paid work. Due to the very high unemployment rate, job creation programs were set up to ease the situation in the short term (Relief). Jobs were created through the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) for unemployed young men between the ages of 18 and 25 whose families were receiving welfare. The CCC was used for reforestation, fighting forest fires, building roads, and combating soil erosion. By 1942, the CCC employed a total of 2.9 million young men. For those U.S. citizens who could not be offered work by the CCC, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration was created, which increased the welfare paid by the states by one-third.

With regard to the public works demanded by the progressive wing of the Democrats, Roosevelt was reserved because these could quickly become a relatively expensive form of poor relief if the projects were unsuitable. He demanded that only projects that were reasonably self-financing should be undertaken. Labor Secretary Frances Perkins succeeded only after several attempts to negotiate the budget up to $3.3 billion. This budget was used to create the Public Works Administration, led by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, to develop infrastructure (roads, bridges, dams, school buildings, sewer systems), especially in underdeveloped regions. It was easier in energy policy, where Roosevelt saw longer-term economic benefits. The Wilson Dam, completed in 1927, was an early public works project initiated by progressives whose use for power generation had been successfully sabotaged for ideological reasons until then, with the help of Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Hoover. To date, the dam had been equally a symbol of hope and frustration for progressives. Wilson Dam, however, inspired Roosevelt and George W. Norris to create the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933. The Tennessee Valley Authority acquired Wilson Dam and had 20 other dams built in the Tennessee Valley by the Public Works Administration. These dams were intended to prevent future flooding, eradicate malaria and provide electricity to the previously underdeveloped region.

Housing policy

In housing policy there was basically a choice between public housing and the promotion of owner-occupied housing. Unlike most European countries, Roosevelt emphasized homeownership. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), established in 1934, insured home equity loans from banks under certain circumstances. Prior to 1934, the situation was that banks made home equity loans only for short terms of 5-10 years. In cases where an FHA guarantee could be successfully applied for, banks made lower-interest loans with terms of up to 30 years. Subsequently, homeownership increased from 4% to 66% of the population, which also boosted the construction industry. Due to the original strict lending criteria, primarily white middle class families benefited from the homeownership subsidy. This policy was sometimes criticized for the fact that the lower third of the population could not benefit from the homeownership subsidy. In the 1990s, under Presidents George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, more generous lending practices were initiated so that poorer families were also assisted in purchasing a home. However, it became apparent that these riskier loans became non-performing to a large extent.

Under the Second New Deal, the United States Housing Authority was established in 1937 to eliminate slums through public housing policies. However, the policy remained limited to helping the poorest of the poor.

Foreign trade policy

With the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, the United States had already abandoned the principle of free trade in response to the recession of 1920/21. Finally, with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, passed under Hoover's presidency, a pronounced protective tariff policy was adopted. There is now a large consensus among historians and economists that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated the Great Depression. It was politically controversial from the beginning; in addition to many prominent scholars, Roosevelt had also opposed the Act. At the instigation of Cordell Hull, the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act was passed in 1934. With this act, the Roosevelt administration laid the first foundations for a customs policy based on the principle of most-favored-nation treatment. Through the conclusion of bilateral trade agreements, American foreign trade was gradually liberalized again.

Second New Deal (1935-1938)

The period from 1935 to 1938 is often referred to as the Second New Deal. This phase was predominantly about long-term solutions.

Political pressure on Roosevelt

After the very successful congressional election of 1934 for the Democratic Party, a so-called midterm election, Roosevelt was able to rely on an even larger Democratic majority. At the same time, however, the political climate changed. Because of the severe economic crisis, the First New Deal had found great bipartisan support among the public and in Congress. Behind this unity, however, the deep policy differences that existed between Democrats and Republicans and within the Democratic Party had only been hidden. These erupted again when the economic situation brightened. After the economy began to recover, wealthy businessmen in particular increasingly criticized the New Deal. They objected to government regulation of the economy, the level of taxes, and the size of welfare and public job creation programs. Conservative ("conservative") Democrats led by Al Smith, who had lost to Roosevelt in the 1932 Democratic Party primaries, formed the American Liberty League in 1934, which had as many as 36,000 members. With financial support from numerous businessmen, the American Liberty League waged a public campaign against the alleged radicalism of the New Deal. The society also supported a racist group that circulated pictures in southern states of the United States depicting the First Lady, known as a civil rights activist, with African Americans. A key financier of the American Liberty League was DuPont heir Irénée du Pont, who believed Roosevelt to be a "Jew-controlled[ed]" Communist. Du Pont, along with his brothers, planned a coup against the president in early 1934. When Smedley D. Butler, a general and New Deal opponent who had been designated for the purpose, informed Roosevelt, du Pont denied having anything to do with it. Criticism of the New Deal also came from the far left and far right. The Communist Party USA, which had grown stronger during the crisis, criticized the New Deal as an attempt to preserve capitalism. Charles Coughlin, classified by historians as a demagogue, who had up to 30 million listeners as a radio host, tried to establish his own political career with anti-Semitic slogans directed against the New Deal.

Politically influential at this time were also, in particular, some personalities sometimes referred to as populists. Francis Everett Townsend suffered the fate typical of older workers at the time of losing his job and his financial reserves in the Great Depression and being unable to find new work. He promoted his Townsend Plan, which provided a state retirement pension for all citizens over the age of 60. The plan was considered unaffordable because a retirement pension of $200 a month was promised; this was higher than an average working wage. In addition, the pensions were to be funded by a new sales tax; this method of funding would have placed a disproportionate burden on low-income people. Still, he was able to muster 20 million supporters for his petition. Democratic Senator Huey Long had initially supported the New Deal, but then turned away from Roosevelt in 1934, whose policies he considered inadequate. He founded the Share Our Wealth Society, which promised every American family a basic annual income of $2,000, to be offset by a radical taxation of high incomes and wealth. While the plan was fiscally unfeasible as it stood, the society had 7 million members, and there was no doubt that Long was seeking a presidential run.

The Populists' successes showed Roosevelt, on the one hand, that there would be considerable popular support for the more far-reaching measures against the Depression and for social security advocated by parts of his think tank. On the other hand, they showed that political competition was not to be feared only from conservatives. Many reform-minded congressmen had been elected to Congress, and Roosevelt was determined to keep the initiative. He wanted the measures prepared by his think tank and supported by him to become law before Congress would pass legislation on its own initiative that he might not be able to support. Some historians argue that the second part of the New Deal came about only in response to pressure from the Populists. According to David M. Kennedy, however, the argument against this is that most of the projects had been planned and prepared long before the Populists' successes. Due to the temporal perspective, only the Wealth Tax Act could be seen as a response to the challenge posed by the populists.

introduction of the welfare state

The Great Depression had hit older people particularly hard, who had above-average difficulty finding work and 50% fell below the poverty line. By 1935, many individual state welfare programs existed to alleviate poverty, topped up with federal grants. Unemployment insurance existed until then only in the state of Wisconsin (introduced in 1932, effective from 1934). Public pension plans formally existed in a few states, but they were all, without exception, severely underfunded and thus virtually meaningless. The absence of social insurance made the United States exceptional among modern industrialized nations. Citizens suffered from this fact during the Depression. Under the presidency of Frances Perkins, the introduction of a welfare state on the European model was developed. With its help, social problems were to be overcome. With the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935, the first social insurance programs were introduced in the United States, including Social Security retirement insurance, a widow's pension for the dependents of victims of industrial accidents, and assistance for the disabled and for single mothers. Federal subsidies were also introduced for unemployment insurance schemes run by the individual states. To finance this, a new tax (the payroll tax) was introduced to pay an employer's share and an employee's share to the Treasury. Roosevelt had insisted on a separate tax so that tax revenues could not be used for other purposes. The original Social Security Act fell short of many European models, in part because Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau successfully intervened to ensure that farmers, domestic workers, and the self-employed were not included in pension and unemployment insurance. Morgenthau argued that Social Security would become unaffordable if these populations, typically low-income earners, also received insurance benefits. On the other hand, this effectively left 65% of all blacks in the U.S. and between 70% and 80% in the Southern states uncovered by Social Security. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People described Social Security as a safety net that was "like a sieve with holes just big enough for the majority of blacks to fall through.

Initially, the introduction of public health insurance also failed to gain majority support. Roosevelt hoped, however, that the Social Security Act could be expanded at a later date. This law, which was fiercely opposed by opponents, established government responsibility for social security in the United States for the first time. The payroll tax was levied from 1937, and due to the pay-as-you-go system, the first pension payments (after a 3-year minimum contribution period) were made from 1940.

Labour law

Unions existed long before 1935, and since most employers did not recognize unions, strikes were often violent, with strikers forcibly preventing strikebreakers from entering the factory and employers hiring thugs to protect the factory and disperse strikers. Occasionally, police were also used against strikers, or governors declared a state of emergency and even deployed the army. This led to more and more serious confrontations with many injured and sometimes even dead. In 1934, two union members were killed in one such confrontation in San Francisco. As a result, the local unions called a general strike in which 130,000 workers participated. Of concern to the president was not only the increasing radicalization of labor struggles, but also the influence of the Communist Party USA within the growing labor movements. An attempt to obtain voluntary recognition of unions by employers through the National Recovery Administration (NRA) had been rendered futile by the banning of the NRA. Robert F. Wagner, in particular, therefore pushed for legal recognition of unions. The Wagner Act, passed in 1935, granted workers the right to form unions and collectively bargain for wages and working conditions. Workers could not be fired for union membership since then. A formal right to strike was also established. Even after the Wagner Act was passed, there were violent clashes. A final major highlight was the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, when Chicago police violently broke up a demonstration by working-class families. However, the National Labor Relations Board, introduced by the Wagner Act, subsequently succeeded with increasing frequency in mediating labor disputes. The number of unionized workers doubled from 1929 to 1938, to 7 million. Much of the increase was due to the expansion of unionization into the mass-production industries with large companies, such as Ford and General Motors, that had previously successfully resisted unions. Strikes increased during a transitional period of several years. The influence of the workers on the level of wages and the shaping of working conditions increased.

In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, setting a minimum wage of 25 cents per hour and a workweek limit of 44 hours. Further, child labor by children under the age of 16 was banned. In order to pass the bill through Congress, where Southern congressmen formed a decisive faction, domestic servants and farm workers had to be excluded from the scope of protection. The Roosevelt Administration, however, hoped to expand the scope of the law to include these occupations at a more opportune time later. After the law's enactment, the wages of 300,000 people immediately increased, and 1.3 million people saw their hours of work reduced.

Labour market and economic policy

The economic recovery had begun with the start of the New Deal and was also quite high, with economic growth averaging 7.7% per year, but the unemployment rate fell only slowly. This development was also the focus of the economist John Maynard Keynes. He described the situation as equilibrium with underemployment. Keynes had tried several times to convince Roosevelt of an economic stimulus through deficit spending. Roosevelt's brain trust, however, was divided from the outset between proponents of the strategy of fighting the depression through increased government spending and proponents of the strategy of balancing the budget through budget cuts. The latter notably included Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. As a result, the countercyclical fiscal policy recommended by Keynes was not pursued in the United States between 1933 and 1941. The anti-Depression measures, especially the job creation programs, did increase government spending. But this was largely offset by other measures. Already under Hoover, a substantial increase in the income tax had been passed, which increased government revenues. In addition, Roosevelt had pushed through significant spending cuts, for example in pensions, when he took office (Economy Act). As a result, the federal budget deficit was about 3% per year from 1933 to 1941. Arthur M. Schlesinger thinks that the brain trust was more open to the idea of a Keynesian stimulus policy during the Second New Deal than during the First New Deal. David M. Kennedy doubts this, saying that such a development can hardly be traced to concrete policies.

| Unemployment rate in the year | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 |

| Including persons in job creation schemes | 24,9 % | 21,7 % | 20,1 % | 16,9 % | 14,3 % | 19,0 % | 17,2 % | 14,6 % | 9,9 % |

| Workers in job creation programs were not counted as unemployed | 20,6 % | 16,0 % | 14,2 % | 9,9 % | 9,1 % | 12,5 % | 11,3 % | 9,5 % | 8,0 % |

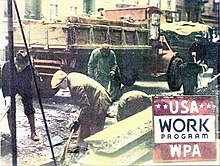

Roosevelt and his brain trust came to believe that unemployment would not disappear as quickly as it had erupted in 1929. They saw a need to extend measures to reduce unemployment. In 1935, the Emergency Relief Appropriation Bill increased the budget for job creation measures by $4 billion. This provided paid work for 3.5 million able-bodied unemployed. At Roosevelt's direction, the job-creation programs had to be designed so that the projects implemented were both labor-intensive and made longer-term sense, and the workers had to be paid less than they would have been in the private sector. Among other things, 125,000 public buildings, more than a million miles of highways and roads, 77,000 bridges, irrigation systems, city parks, swimming pools, etc. were built. Among them were prominent projects such as the Lincoln Tunnel, the Triborough Bridge, New York-LaGuardia Airport, the Overseas Highway and the Oakland Bay Bridge. In addition to the Public Works Administration, which had already been founded in 1933, the Works Progress Administration under the direction of Harry Hopkins was primarily responsible for these projects from 1935 onward. The Rural Electrification Administration, founded in 1935, also worked with these funds to supply rural regions with cheap electricity. In 1935, only 20 % of American farms had access to electricity; ten years later, the rate was already 90 %.

Competition law

Large holding companies caused some problems. For example, a few holding companies dominated the entire energy market. Many were also so large that they could exert considerable influence on legislation. At that time, there were many pyramidal, or multi-level, holding companies in the United States. Here, the operating part of the company had to generate excessive profits to fund the various higher-level companies. With the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, all holding companies had to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). All holding companies more than two-tiered that could not give a valid reason for this structure were broken up.

Tax law

1935 also saw the passage of the Wealth Tax Act, which raised the top income tax rate to 79%. However, the act was primarily intended to facilitate the election campaign for Roosevelt, as it was a response to the threat to the Democratic Party by Huey Long and Charles Coughlin, who were described as radicals. Treasury Secretary Morgenthau described the Wealth Tax Act to Treasury officials as a campaign document, a bill that was intended to raise government revenues only marginally. While the top tax rate of 79% was very high, it was only to be applied to very high incomes. In fact, there was only one taxpayer who had to pay the top tax rate of 79% after this law was passed: John D. Rockefeller.

In 1936, a corporate income tax was enacted with rates ranging from 7% to 27%. In Congress, the law was weakened - smaller corporations were largely exempt from the regulations. Unlike the Wealth Tax Act, the focus of this law was on increasing tax revenue, since shortly before Congress had passed a law on its own initiative that brought forward the payment of outstanding bonuses for World War I veterans - a total of $2 billion - from 1945 to 1936.

Constitutional amendment of 1937

When Roosevelt took office, the Supreme Court was staffed mostly by justices (for life) nominated by Republican presidents. In the 1920s and 1930s, four of the Supreme Court justices became known as the Four Horsemen of Reaction, who repeatedly succeeded in organizing a majority (at least 5 of the 9 justices) that declared quite a few progressive laws unconstitutional. On May 27, 1935 (Black Monday), the first New Deal laws, including the work of the National Recovery Administration, were declared unconstitutional. At this point, Roosevelt was still hoping that one of the justices would retire and that the majority balance could be changed by a new judicial nomination. After other laws were declared unconstitutional in 1936, most notably the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the New York State minimum wage law, Roosevelt came to believe that the Supreme Court would overturn all major parts of the New Deal and effectively undermine the principle of separation of powers between the judicial and legislative branches in favor of the judicial branch. Former President Hoover also criticized the decisions as going too far in encroaching on legislative powers. Criticism was widespread among the public (including, for example, in the best-selling book by Drew Pearson and Robert Allen entitled Nine Old Men) that the judges, most of whom were over 70 years old, no longer even recognized the problems of the present. Affirmed by his high electoral victory in the 1936 presidential election and angered by Judge McReynolds' comment "I'll never retire while that crippled son of a bitch is still in the White House.", Roosevelt decided to make his plans for judicial reform public in January 1937. The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 was intended to give the American president the power to appoint additional new judges for every judge over 70 who refused to retire. The bill was initially backed by a sufficient majority of Democratic members of the House and Senate. However, it was sharply criticized by Republicans as well as by some Democratic congressmen as an encroachment on the separation of powers. In addition, Democratic congressmen from southern states feared that progressive judges might critically review the separate-but-equal jurisprudence on racial segregation. At this point, beginning on March 29, 1937 (White Monday), a change in Supreme Court jurisprudence occurred. Justice Owen Roberts, who had previously voted frequently with the Four Horsemen, now voted with the progressive wing of the Court. The change was most evident in the judicial decision declaring Washington State's minimum wage law constitutional - only a year earlier, New York's minimum wage law had been declared unconstitutional. The Wagner Act and Social Security Act were also declared constitutional. Historian David M. Kennedy believes that increasing public criticism of the Four Horsemen of Reaction's jurisprudence and Roosevelt's landslide election victory in November 1936 played a role in the change in jurisprudence. Despite this turn of events, Roosevelt attempted to get the Judicial Reform Act through Congress but failed in this effort. The voluntary retirement of the Four Horsemen (Van Devanter in 1937, Sutherland in 1938, Butler in 1939, and McReynolds in 1941) and three other justices largely recast the Supreme Court. After the period of conservative jurisprudence, a prolonged period of liberal constitutional jurisprudence began in 1937.

William Rehnquist summarized the constitutional change as follows:

"President Roosevelt lost the Court-packing battle, but he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by any novel legislation, but by serving in office for more than twelve years, and appointing eight of the nine Justices of the Court."

"President Roosevelt lost the battle over the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, but he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by novel legislation, but by being in office for more than twelve years and thus being able (gradually) to appoint eight of the nine Supreme Court justices."

President Roosevelt signing the Social Security Act on August 15, 1935.

Contemporary advertising poster for the Social Security Act

Franklin D. Roosevelt (center) and Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins (right) at the signing of the Wagner Act (1935).

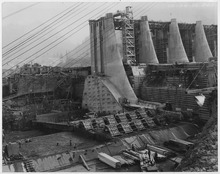

Bonneville Dam was one of the Public Works Administration's dam projects.

Companies that pledged to compete fairly and refrain from layoffs were allowed to advertise with the Blue Eagle.

.jpg)

Franklin D. Roosevelt (seated) and George W. Norris (front right) at the founding of the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933)

By executive order 6102, private gold ownership was banned in 1933.

The billboard advised bank customers that deposits of up to $2,500 per customer are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

People line up outside American Union Bank to liquidate their bank balance (bank run).

The Works Progress Administration designed a number of job creation schemes (e.g. road construction).

Memorial Day Massacre of 1937: Policemen broke up a demonstration of working-class families. Ten demonstrators were shot dead, seven of them by gunshots in the back. Among the thirty injured were a woman and three children.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the New Deal?

A: The New Deal was a series of programs launched by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to solve the problems caused by the Great Depression.

Q: How is the New Deal split?

A: The New Deal is often split into two smaller New Deals: the First New Deal and the Second New Deal.

Q: What happened during the First Hundred Days of Roosevelt's presidency?

A: During the First Hundred Days of Roosevelt's presidency, Roosevelt and his administration proposed many plans to fix the economy.

Q: What was the percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1930?

A: The percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1930 was 11.6%.

Q: What was the percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1999?

A: The percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1999 was 13.9%.

Q: What are some of the programs launched under the New Deal?

A: Some of the programs launched under the New Deal include the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), WPA (Works Progress Administration), AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Act), TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority), HOLC (Home Owners Loan Corporation), FERA (Federal Emergency Relief Administration), PWA (Public Works Administration), CWA (Civil Works Administration) and NRA (National Recovery Administration).

Q: What was the percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1945?

A: The percentage of non-agricultural workers in labor unions in 1945 was 35.5%.

Search within the encyclopedia