Nazism

![]()

This article is about National Socialism as an ideology. For the period of rule see Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, for precursors and various, partly related ideologies see National Socialism.

National Socialism is a radically anti-Semitic, racist, nationalist (chauvinist), völkisch, Social Darwinist, anti-communist, anti-liberal and anti-democratic ideology. It has its roots in the völkisch movement, which developed around the beginning of the 1880s in the German Empire and in Austria-Hungary. From 1919, after the First World War, it became an independent political movement in the German-speaking world.

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), founded in 1920, came to power in Germany under Adolf Hitler on January 30, 1933, transforming the Weimar Republic into the dictatorship of the Nazi state through terror, violations of the law, and the so-called Gleichschaltung. The Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 triggered the Second World War, during which the Nazis and their collaborators committed numerous war crimes and mass murders, including the Holocaust of some six million European Jews and the Porajmos of the European Roma. The era of National Socialism ended with the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on 8 May 1945.

Since then, coming to terms with the Nazi past has influenced politics. Nazi propaganda, the use of symbols of the time and political activity in the National Socialist sense have been banned in Germany and Austria since 1945. Similar bans exist in other countries. Neo-Nazis and other right-wing extremists continue to advocate National Socialist or related ideas and goals. In Nazi research, it is disputed whether National Socialism can be described with generalizing terms such as fascism or totalitarianism or whether it was a singular phenomenon.

Adolf Hitler in 1927 as a speaker at the third Reich Party Congress of the NSDAP (the first in Nuremberg). Heinrich Himmler, Rudolf Heß, Franz Pfeffer von Salomon and Gregor Strasser can be seen in the background.

Designations

In the German-speaking world, "national socialism" has referred to combinations of nationalist and socialist ideas since about 1860. The first to speak of "National Socialism" was the German Workers' Party, founded in Austria in 1903, which renamed itself the German National Socialist Workers' Party (DNSAP) in 1918. Accordingly, the German Workers' Party (DAP), founded in Germany in 1919, also renamed itself the NSDAP in 1920.

With the designation "National Socialism," these new parties demarcated their ideology from the internationalism of the Social Democratic and Communist parties and from the conservative nationalism of older parties by offering themselves as a better alternative to their constituencies (workers and middle class). In addition, they placed individual anti-capitalist demands within the framework of a völkisch-racist nationalism and, from 1920 onwards, presented themselves as a "movement" rather than a party, in order to reach protest voters and those disillusioned with politics.

Today, the term usually refers to the particular ideology of Adolf Hitler and his followers. Hitler defined "nationalism" as the devotion of the individual to his national community; he called its responsibility for the individual "socialism". He firmly rejected the socialization of the means of production, a major goal of socialists. According to the historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler, socialism lived on in the NSDAP only "in a verbalized form" as a national community ideology.

Moreover, the NSDAP distinguished its National Socialism from Italian Fascism. Fascism, however, has since 1925 (starting from the Soviet Union) often served as an umbrella term for "National Socialism" ("Hitler's fascism"), Italian fascism and related anti-communist ideologies, regimes and systems. In Marxist theories of fascism, National Socialism is classified as a form of fascism. Non-Marxist scholars who explain National Socialism as a variety of fascism include Ernst Nolte, who in his work Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche (1963) characterized it as "radical fascism" in distinction from Italian "normal fascism", and Wolfgang Benz, who in 2010 described it as the "most radical manifestation of fascist ideologies". Jörg Echternkamp argues that only the system of coordinates developed by transnational fascism research allows for a classification of National Socialism and a comparison with other movements. However, the affinity between them, which many scholars affirm, is less evident in their respective programmes than in their actionism and immense willingness to use violence.

After 1945, National Socialism was referred to as totalitarianism, especially in the USA and the former Federal Republic of Germany, and under this umbrella term was paralleled with the ideology and system of rule of Stalinism. Fascism and totalitarianism theories are controversially discussed in research. Historians Michael Burleigh and Wolfgang Wippermann argue that subsuming National Socialism under one of these theories misses its essence, the racial ideological program. According to French psychoanalyst Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel and German social scientist Samuel Salzborn, applying the concept of fascism to National Socialism rationalizes the Holocaust and thereby trivializes it. This, they argue, unconsciously serves to repress and deflect the guilt of the parents' or grandparents' generation. For these and other reasons, these researchers, as well as Karl Dietrich Bracher and Bernd Martin, advocate viewing National Socialism as an independent and singular phenomenon.

The terms "Nazis" for the National Socialists and "Nazism" for their ideology became common since the 1920s among their opponents in the workers' movement, later also among the liberated prisoners of Buchenwald concentration camp and in the GDR. Today's supporters of National Socialism are often called "neo-Nazis".

Origin

German anti-Semites had organized themselves into several political parties, many groups and associations since 1879. The anti-Semitic parties wanted to end and revise Jewish emancipation, but failed to achieve their goals. After losing votes in the Reichstag elections of 1912, new, non-partisan anti-Semitic clubs and associations were formed, such as Theodor Fritsch's Reichshammerbund, the "Verband gegen die Überhebung des Judentums," and the secret Teutonic Order, from which the Munich Thule Society emerged in 1918. Its magazine, the Münchener Beobachter, with the swastika as its title symbol, became the party organ of the NSDAP, the Völkischer Beobachter.

Another precursor of National Socialism was the small, extremely nationalistic and imperialistic All-German Association (founded in 1891). It sought a belligerent expansion of German "Lebensraum" and a policy of subjugation. During World War I, its strong anti-Semitic propaganda led to the state census of Jews in 1916. After 1918, it called for a "national dictatorship" against "foreign peoples.

In 1914, the Deutschnationale Handlungsgehilfenverband was founded, and two older anti-Semitic parties united as the Deutschvölkische Partei (DVP). In the course of the war, this party united with the All-German Association. On the initiative of the All-German Association, towards the end of the war dissolved groups united with newly founded völkisch groups such as the Deutsch-Österreichischer Schutzverein Antisemitenbund, the Deutschvölkischer Beamtenvereinigung and the Bund völkischer Frauen to form the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund. This had about 200,000 members in 600 local groups in 1920, but was banned after the Hitler-Ludendorff putsch in 1923. After the re-admission of the NSDAP, it lost influence to it and was completely dissolved in 1933.

Moreover, since the October Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War, many anti-Communist groups spread, among others through Russian refugees. Under the propaganda slogan "Jewish Bolshevism," national conservative elites and Freikorps formed from front-line soldiers equated Jews and Communists. They also often espoused the conspiracy theory of an alleged world-dominating Jewry. Among them was the "Economic Reconstruction Association" founded in Munich in 1920. This supported the NSDAP financially and ideologically.

In National Socialism, these currents and groups merged their racist, nationalist "all-German" and imperialist ideas and goals. The strongest supporting link of their diverse ideas was anti-Semitism. Since the November Revolution of 1918, this has also manifested itself as a radical rejection of the Weimar Republic, which these groups denounced as a "Jewish Republic" created by November criminals. The Völkische defined their worldview as a strict opposition to the Marxism of the left-wing parties, to the political Catholicism of the Centre Party and to their fiction of a "world Jewry". Parts of the Völkisch movement also already advocated ideas of "human breeding" (eugenics).

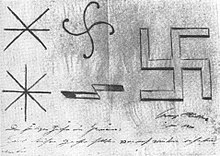

Swastika sketch of Hitler from 1920 with the note: "The sacred signs of the Teutons. One of these signs should be raised again by us."

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Nazism?

A: Nazism is a set of political beliefs associated with the Nazi Party of Germany. It is an extreme right-wing, fascist ideology that was heavily inspired by the works of Oswald Spengler.

Q: When did the Nazi Party gain power?

A: The Nazi Party gained power in 1933 and began carrying out their ideas in Germany, which they called the Third Reich.

Q: What did Nazis believe about the Aryan race?

A: The Nazis believed that only the Aryan (German) race was capable of building nations and other races were agents of corruptive forces such as capitalism and Marxism. They also considered the Aryan race to be the 'Master race', meaning they thought they were more biologically evolved than other humans and deserved to have power over them.

Q: What reforms did some Nazis want to implement?

A: Some Nazis wanted to eliminate economic classes in Germany and for the government to take control of major businesses. These reforms would have gone further than what Hitler had planned, so many of these Nazis were murdered on his orders during what became known as "The Night of Long Knives".

Q: Who did the Nazis blame for Germany's defeat in World War I?

A: The Nazis blamed the Jewish people for Germany's defeat in World War I; this is known as "The Stab in the Back Myth". They also blamed Jews for rapid inflation and practically every other economic woe facing Germany at that time due to their defeat in WWI.

Q: What propaganda tactic did they use against Jewish people?

A: The Nazis used a propaganda tactic known as scapegoating against Jewish people, where they lazily yet effectively blamed them for all problems facing Germany at that time. This was used to justify atrocities committed by them against Jews during WWII.

Q: How did they implement racist ideas?

A: To implement racist ideas, Nuremberg Race Laws (created 1935) banned non-Aryans and political opponents from civil service, while forbidding any sexual contact between 'Aryan' and 'non-Aryan' persons. Millions of Jews, Roma, and other people were sent to concentration camps or death camps where they were killed; these killings are now referred to as "the Holocaust".

Search within the encyclopedia