Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Indian is the collective term used in German for the indigenous peoples of the Americas, with the exception of the Eskimo peoples, the Aleuts of the Arctic regions and the population of the American Pacific Islands. Their ancestors settled the Americas from Asia in prehistoric times and developed a variety of cultures and languages there. Indians is a foreign term used by the colonialists; there is no corresponding self-titling of the far more than two thousand groups. However, there are overlapping terms in Canada, in the USA as well as in the former Spanish and Portuguese part of America.

Their ancestors first developed the hunter-gatherer culture they had brought with them, soon living mainly on land mammals such as bison, caribou and guanacos or on birds such as nandus. But they also traveled the Pacific along the coast shortly after or already during the last cold period. Pottery, agriculture (such as the cultivation of pumpkins, which began before 4000 B.C.) and graduated forms of sedentarism, as well as very early long-distance trade, characterized the cultures in the north of the continent, while in the south of North America livestock breeding and irrigation farming led to higher yields and, before 3000 B.C., to urban cultures that extended northward to the Mississippi River and into southern Canada. The outstanding breeding successes of the peasant Indians of Central and South America can be credited with the cultivation of avocado, potato, tomato, corn, pineapple, pepper, tobacco, as well as alpaca wool and the guinea pig, among others. In addition, many wild prey cultures continued to exist in large parts of the double continent, most of which were organized nomadically in small hordes or larger segmentary or tribal societies.

In what is now Latin America, the Spanish conquistadors destroyed the great empires of Central and South America within a few decades in the 16th century. Even more destructive, however, were the diseases introduced by the Europeans, especially smallpox. In some regions, such as the Caribbean, genocide took place against the indigenous population, which was then replaced by African slaves; in other regions, such as South America, Indian and European populations intermingled. Only in some areas, such as Bolivia and southern Mexico, are Indians still in the majority today. In Bolivia, from 2006 to 2019, Evo Morales was the first indigenous president of the country and leader of the ruling socialist party. Today, the policies of industrial and agricultural exploitation, deforestation and the exploitation of mineral resources pose a particular threat to their local communities, which in South America are still strongly tied to their natural environment and, to a small extent, live in isolation again.

In North America, the Indians gradually became a minority from 1600 onwards. This process of displacement continued into the 20th century. The European immigrant societies regarded the Indians as "inferior" and attempted to displace them, initially in an uncoordinated manner, but soon systematically: military subjugation, sometimes extermination, was followed by a targeted assimilation policy, initially above all by taking children away to boarding schools; attempts to turn the Indians into settled farmers; in addition, by segregation in Indian reservations, forced resettlement and segregation.

The consequences of trauma have long been underestimated or ignored. Since the end of the 20th century, churches and some governments have apologized for abuses, genocides and cultural destruction. Since the beginning of the 21st century, attempts at reparations have been made. They are also gaining opportunities for participation and skills to enforce contractual and political rights.

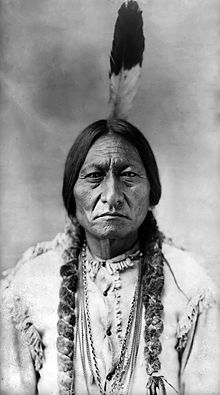

Sitting Bull, chief and medicine man of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux. Photo by David Frances Barry, 1885

.jpg)

John Ross, Cherokee chief from 1828 to 1866; color lithograph, ca. 1843.

Population and reservations

→ Main articles: Indigenous peoples of South America, Indians of North America, and First Nations.

The Indian population of the Americas is very unevenly distributed, with several thousand reservations. Yet most Indians in Central and South America do not live on reservations.

While in Canada in 2006 just under 700,000 people (2.1% of the population) were considered Indians and 615 tribes were recognised on around 3000 reservations, in the USA there were 566 tribes recognised by the federal government, representing 0.97% of the population, and around 245 unrecognised tribes. Within the states, emphases can be equally discerned. For example, the majority of U.S. Indians live in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. In total, around 3.5 to 4 million Indians live in North America.

In Latin America, on the other hand, there are 65 to 70 million Indians, about half of them in Mexico and a third in the Andean countries. Only in Bolivia do they head the government. The demarcation from the rest of the population is less sharply defined, reservations exist mainly in Brazil, Colombia, Panama, Paraguay and Venezuela and are mostly located in the forest areas of the Orinoco, Paraná and Amazon basins.

In Mexico alone, the indigenous population is estimated at 30% of the over 100 million Mexicans. Mestizos make up another 60% of the total population. In Belize, they are estimated at 10% and 45% of the population, respectively. In Guatemala, 59.4% are mestizos (called Ladinos here), and 45% of the population belongs to various Mayan groups. Of these, 9.1% are Quiché, 8.4 Cakchiquel, 7.9 Mam, 6.3% Kekchí, and another 8.6% belong to other Maya groups. In neighbouring Honduras, the proportion of Indians is 7%, and that of Mestizos 90%, similar to El Salvador, but where Indians now make up only 1% of the population. In Nicaragua, the proportion of mestizos is 69%, that of Indians 5%. In Costa Rica, the proportion of Indians is only about 1%, and in Panama it is 5%. The Caribbean is an extreme, as for example in Cuba there are practically no Indians left, similar to Jamaica. On Dominica, 300 to 500 Caribs live in their own reservation.

In South America there are also focal points. While the proportion of Indians in Colombia is only 1%, the proportion of mestizos there is 58%, and 3% are descendants of blacks and Indians. In Guyana the proportion of Indians is 9.1%, in Suriname 2%. The proportion is considerably higher in the Andean states, such as Ecuador, where 25% of the population are Indians, in Peru 45%, in Bolivia even 55% - 30% are Quechua and 25% Aymara.

Further south, in Chile, the proportion of the Indian population is only just under 5%, most of them Mapuche. In Argentina their share is less than 3%, in Uruguay there are almost no Indians, in Paraguay their share is around 5%, but in Brazil it is less than 1%.

In North America, Indians often live on reservations, called reserves in Canada and reservations in the United States. In Canada, the reservations came into being as a result of treaties that the Indians concluded with the government. Commissions determined the reserve boundaries after consulting the Indians, but without involving them in the decision. Within these areas, they were entitled to their traditional rights and did not pay taxes on sales made there. Today, about half of the Indians live in cities.

The Indian policy of the United States changed direction several times. All tribes were forced to leave their homes east of the Mississippi River beginning in 1830, and often several tribes were grouped together on one reservation. Although many of the rural Indians lived in poverty, some tribes managed to recover economically. According to the 2000 census, about 85% lived off reservations, mostly in cities.

In Brazil and in the neighbouring countries there are still isolated peoples, groups that have had such bad experiences in contacts with whites that they try to avoid them. In Brazil alone, it is estimated that there are about 67 groups.

Reservations in the USA (without Alaska)

Indian Reserves in Brazil

Xavantes in their reserve Maraiwatséde

Languages

→ Main article: Indigenous American languages

Languages consist of dozens of distinct language families as well as many isolated languages. There have been several attempts by linguists to group them into superordinate families, none of which is generally accepted. Two language families diverge markedly from the others: The Na-Dené languages and the Eskimo-Aleutic languages. Genetic analyses of the Indians suggest several waves of immigration in the settlement of the Americas. Therefore, it can be assumed that these languages are spoken by Indian peoples who came to America as later immigrants, when the other peoples had already settled the continent.

Only Indian cultures in Central America have developed writings. The oldest evidence comes from the Olmecs in Central America and is dated to about 900 BC. Other scripts also developed here, especially those of the Maya, Mixtecs, Zapotecs and Aztecs. There was a range of variation between still purely logographic writing to a largely phonetic script.

History of languages in America

After the colonization of the Americas, the attitude towards indigenous languages ranged from neglect to targeted suppression. Only the missionary orders began early to learn the languages and to establish appropriate schools. This was true first in Peru, where a high school was established, then in numerous missionary areas between Quebec and California in the north, through the Mexican metropolitan areas to the border areas in southern Chile and along the Portuguese border (Brazil). Occasionally, they thereby spread languages to areas where that language had not previously been in use, as in the case of Quechua. Besides languages with millions of speakers, such as Aymara, Guaraní and Nahuatl, the missionaries learned only a few languages, which in turn strengthened their survival.

In North America, the use of indigenous languages was actively suppressed for a long time. This policy culminated in the so-called Termination with the aim of detaching Indians from their tribal association and integrating them into society as individuals. To this end, in particular, the use of Indian languages in schools was strictly forbidden. It was not until 1958 that this goal was abandoned, and since then there have been numerous attempts to revive North American languages.

Distribution today

In North America, some of the larger languages, such as Cree (with 60-90,000 speakers) in Canada or Navajo in the southwestern U.S. (with about 150,000 speakers) are not endangered, while others are on the verge of extinction. In Canada, at least 74 languages are still in use.

Mayan languages dominate in Mexico and neighboring countries to the south. Mexico recognizes 62 national indigenous languages, with more than 6 million residents over the age of 5 claiming one of these languages as their mother tongue in 2005.

In the Caribbean, the languages of the Cariben and the Arawak are only rarely spoken; among their representatives are the Taíno.

The situation is different in South America. According to estimates, about 1500 languages were spoken there before Columbus, of which about 350 still exist today. The classification into language families is, as in the whole of America, highly controversial. The number of speakers is considerably higher than in North America and the Caribbean, but at the same time most of them are concentrated in a few languages. These in turn were learned and promoted by missionaries. Thus, numerous languages survived, for which materials are now available in writing and via the Internet.

While in the eastern lowlands of South America Tupí languages predominate, the largest branch of which are the Tupí-Guaraní languages, the Andean region is dominated by Quechua languages, which were already used by the Incas. In addition, there are large language groups, such as the Aymara languages, which include Aymara, the indigenous language with the most speakers in South America (about 2.2 million). In Argentina, about a quarter of a million people speak one of the two Araucanian languages.

Predominantly in North America, new languages arose in contact between whites and Indians, especially mixed languages such as Chinook Wawa on the Pacific coast, because extensive trade required a simple language of communication. Added to this were languages such as Michif, the most important Métis language in Canada, which arose from Indian and European languages in the formation of a mixed people and has origins in Cree and French. Bungee, also spoken by Métis, on the other hand, has Scottish Gaelic and Cree roots.

Bolivia, Paraguay, Ecuador, and Peru now recognize one or more indigenous American languages as official languages in addition to Spanish.

Distribution areas of the indigenous languages of North America before colonization

Indio languages in Mexico with more than 100,000 speakers

Questions and Answers

Q: Who are Native Americans?

A: Native Americans are the indigenous peoples and their descendants who were in the Americas before Europeans arrived.

Q: What is another name for Native Americans?

A: Other names for Native Americans include Aboriginal Americans, American Indians, Amerindians or indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Q: Why do some people think calling a Native American an Indian is racist?

A: This may be confusing because it is the same word used for people from India. When Christopher Columbus explored, he did not know about the Americas and thought he was in the East Indies, so he called the people Indians. Today, some think that calling a Native American an Indian is racist because it perpetuates this misunderstanding.

Q: How many different tribes of Native American people exist?

A: There are many different tribes of Native American people with many different languages. Some tribes were hunter-gatherers who moved from place to place while others lived in one place and built cities and kingdoms.

Q: What happened to many native people after Europeans came to the Americas?

A: Many native people were hurt, killed or forced to leave their homes by settlers who took their lands due to diseases that came with the Europeans as well as battles with them.

Q: How many Native Americans live today?

A: Today there are more than three million Native Americans in Canada and the U.S combined and about 51 million more living in Latin America.

Q: What challenges do some modern dayNative Americans face?

A: Many modern dayNativeAmericans still speak native languages and have their own cultural practices while others have adopted some parts of Western culture but they all face problems with discrimination and racism.

Search within the encyclopedia