Muhammad Ali Jinnah

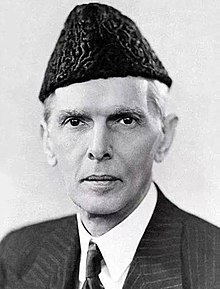

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Urdu محمد علی جناح; Gujarati:મહંમદ અલી ઝીણા) (born 25 December 1876 in Karachi; † 11 September 1948 ibid) was a politician and resistance fighter in British India and is considered the founder of the state of Pakistan. He is honored in Pakistan as Qaid-e Azam (قائد اعظم "Greatest Leader") and Baba-e-Qaum (بابائے قوم "Father of the Nation"). His birth and death anniversaries are national holidays in Pakistan.

Jinnah came to prominence in the Indian National Congress when he propagated the political unity of Hindus and Muslims. He helped forge the Lucknow Pact between the Congress Party and the All-India Muslim League in 1916 and became one of the most important figures in the All India Home Rule League over it. Differences with Mahatma Gandhi led Jinnah to leave the Congress Party in 1920. He assumed the presidency of the Muslim League the same year and later proposed his Fourteen Point Plan to secure the political rights of Muslims in a self-ruled India. Disillusioned by the failures of his efforts and the disunity of the League, Jinnah went to London for many years. Various politicians urged him to return to India in 1934 and reorganize the League. Disappointed with the Congress Party, the Muslim League proposed the partition of India and the creation of an independent separate state of Muslims in the Lahore Resolution. In the 1946 elections, the League won most of the Muslim seats in Punjab, Bengal and Sind. This led to the colonial power agreeing to the partition of India. As Pakistan's first governor-general, Jinnah made efforts to reintegrate the many millions of refugees and outline national foreign, security and economic policies. He died only a few months after the founding of the state.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, 1945

Life and work

Childhood and youth

Jinnah was born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai, the eldest child of a wealthy merchant in Wazir Mansion in Karachi (now Pakistan). The earliest evidence from his school register suggests that Jinnahs was born on 20 October 1875, but his first biographer Sarojini Naidu gave 25 December 1876 in 1917. Since then, this date of birth has been recorded in all official documents, including Jinnah's passport. His father Jinnahbhai Poonja (1857-1901) had emigrated from Sindh province to Kathiawar. His grandfather, before converting to Islam, belonged to the same caste as Gandhi. Muhammad had six younger siblings: first came his three brothers Ahmad Ali, Bunde Ali and Rahmat Ali, then three sisters Maryam, Fatima and Shireen. His family belonged to the Ismaili Muslim Shia. The language of the family at home was Gujarati.

Jinnah was first educated at home. From 1887, he went to school at Sind Madrasat al-Islam in Karachi, which became the present Sindh Madressatul Islam University. Later, he attended the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi. There, at the age of 16, he passed the matriculation examination for admission to the University of Bombay. An English friend of his father offered Jinnah to work as an apprentice in his company, Grahams Shipping and Trading Company in London. Jinnah's father agreed to the plan. Before he even left for London, Jinnah was married in an arranged marriage to his cousin Emibai, who was two years younger; the couple were 16 and 14 years old at the time of the marriage. While Jinnah was in London, his young wife, who had remained in India, died, as did his mother. Jinnah soon quit his employment as an apprentice to study law at Lincoln's Inn. In 1895 he graduated with an examination as a barrister. From this point Jinnah began to become politically involved as an admirer of the Indian politicians Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Pherozeshah Mahta.

Along with other Indian students, Jinnah participated in Naoroji's election campaign for a seat in the British House of Commons. He developed views of a staunch parliamentarian and constitutionalist who advocated Indian self-government while disdaining the arrogance of British officials and discrimination against Indians.

Jinnah, who was considered blameless in personal matters and had absolute integrity in money matters, came under considerable pressure when his father's business went bankrupt. He moved to Bombay and became a brilliant and successful lawyer, particularly famous for handling the Caucus case, which he argued in the Bombay High Court in 1905 at the behest of Pherozeshah Mahta. Jinnah built himself a house in Malabar Hill, which later became known as Jinnah House. He was not a strict practicing Muslim, enjoyed drinking champagne, Bordeaux wine, Chablis, Cognac, liked to eat oysters and caviar, shaved carefully every day, dressed in impeccable European clothes for life, preferred tailored white linen suits and two-tone shoes, avoided the mosque on Fridays and spoke English better than his native Gujarati. In Urdu, the language familiar to most Indian Muslims, Jinnah could speak only a few sentences. His reputation as a skillful lawyer prompted the Indian politician Bal Gangadhar Tilak to hire him as his counsel at his trial for sedition in 1905. Jinnah deftly pleaded that it was not sedition for an Indian to demand freedom and self-government for his own country, but Tilak nevertheless received a rigorous prison sentence.

Early political career

In 1896, Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress, India's largest political organization at the time. Like the majority of the Congress at the time, Jinnah was not in favor of complete independence, given what he saw as the benefits of British influence on education, law, culture, and industry for India. He met Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who exerted a strong influence on him; Jinnah pursued the goal of becoming a "Muslim Gokhale" at the beginning of his political career. On January 25, 1910, Jinnah became a member of the sixty-member Imperial Legislative Council. This council had no real power or authority. It included a large number of unelected British Indian loyalists and Europeans. Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passage of the "Act to curb child marriage", the legitimization of the Muslim Waqf - religious endowments - and was appointed to the Sandhurst Committee which established the Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun. During World War II, Jinnah was among those moderate Indians who supported the British war effort, hoping Indians would be rewarded by political freedoms.

Jinnah initially avoided joining the All India Muslim League, founded in 1906, because he considered it to be of only local importance. In 1913, however, he joined it without leaving the Congress Party and became its president at the Muslim League's annual convention in Lucknow in 1916. Under his leadership, it increasingly developed into a political party distinct from the rival Congress Party. He became the architect of the Lucknow Pact between the Congress Party and the Muslim League concluded in the same year, succeeding in presenting them as a united political front to the British on most issues of self-government. Jinnah also played a significant role in the formation of an All India Home Rule League in 1916. Along with other leading politicians Annie Besant and Tilak, he called for Home Rule for India, the status of a self-governing dominion in the British Empire similar to the status of Canada, New Zealand and Australia. During the Bombay chapter of the League, he presided over it.

During a holiday stay at the Mount Everest Hotel in Darjeeling, the 41-year-old seemingly confirmed bachelor Jinnah met Rattanbai Petit ("Ruttie"), the 17-year-old daughter of his close friend Sir Dinshaw Petit, with whom he fell madly in love, contrary to all social conventions prevailing in India at the time, since Ruttie, who came from Bombay, belonged to the country's Parsi elite. Petit was so enraged by the budding love that the friendship broke down over it and he obtained a court order restraining Jinnah from seeing Ruttie again. However, Ruttie apparently returned Jinnah's feelings and eloped on her eighteenth birthday to marry Jinnah, 24 years her senior, in 1918 against the wishes of Parsi and orthodox Muslim society. However, she overrode her family, nominally converted to Islam and took the name Maryam (she never used it), which led to her estrangement from her family and the Parsi community. The couple lived in Bombay and traveled frequently throughout India and Europe. In 1919, she bore Jinnah their only child together, daughter Dina Wadia.

Fourteen points and "exile"

Jinnah's problems with the Congress Party began with the rise of Mohandas Gandhi in 1918, who recommended nonviolent civil disobedience as the best method for all Indians to achieve swaraj (independence or self-government). In contrast, Jinnah considered only constitutional struggle as a means to independence. Civil disobedience was for the ignorant and illiterate, he lectured Gandhi. Unlike most Congress leaders, Gandhi did not wear Western-style clothes, strove to use one of India's vernacular languages instead of English, and was deeply religious. Gandhi's "Indianized" style of leadership was highly regarded by the Indian people. Jinnah criticized Gandhi's support for the Caliphate campaign beginning in 1919/1920, which Jinnah took to be support for a religious zealotry. In 1920, Jinnah withdrew from the Congress Party, warning that Gandhi's methods of mass struggle would lead to division between Hindus and Muslims and further within the two religious groups.

At the beginning of his presidency of the Muslim League, Jinnah was drawn into a conflict between the pro-Congress faction and the pro-British faction. In 1927, Jinnah entered into negotiations with Muslim and Hindu politicians on the question of a future constitution while fighting the wholly British Simon Commission. The League called for separate elections, while the Nehru Report favoured joint elections. Jinnah himself thought nothing of separate elections, but formulated compromise proposals and made other demands which he believed would benefit both sides. His program became known as The 14 Points of Mr. Jinnah. Both the Congress Party and the other political parties rejected his 14 points.

Jinnah's private life, and especially his marriage, suffered during this period because of his political work. The sensationally beautiful, fun-loving Ruttie loved to dress in transparent, figure-hugging saris and shock Bombay's staid society. Although they worked to save their marriage by travelling together to Europe when he was appointed to the Sandhurst Committee, the eloquent Indian nationalist left Jinnah, who was anxious for his respectability and dearly loved her, in 1928 and died a year later from an overdose of morphine taken for chronic colitis. Jinnah was deeply affected by her death. At her open grave in Bombay's Islamic cemetery, he wept publicly for the first time. The otherwise stiff and aloof, almost emotionless man showed emotion publicly for the first time.

At the round table conferences in London, Jinnah criticized Gandhi but became disillusioned when the talks broke down. Frustrated by the Muslim League's disunity, he decided to leave politics and work as a lawyer in England. His sister Fatima Jinnah, a previously practicing dentist, took care of him ever since, living and traveling with him and becoming his closest advisor. She helped him raise his daughter, who enjoyed her education in England and India. After his daughter later decided to marry Neville Wadi, a Parsi-born Christian businessman, he became estranged from his daughter, although he himself had to deal with the same problems in 1918 when he married Rattanbai. Jinnah continued his cordial correspondence with his daughter, but their personal relationship remained strained. Dina lived with her family in India ever since.

Muslim League leader

Prominent Muslims such as the Aga Khan, Choudhary Rahmat Ali, A.R. Dard and Muhammad Iqbal made advances to persuade Jinnah to return to India. Rahmat Ali invited Jinnah to a banquet of oysters and chablis at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in London in the spring of 1933 to persuade him to take over the now reunited Muslim League. Eventually, Jinnah returned to India in 1934, got himself elected permanent president, and began to reorganize the party, aided by Liaquat Ali Khan, who acted as his right-hand man. In the 1937 elections to the provincial governments, held as part of an effort to reform the constitution, the League proved to be a competent party, winning a significant number of seats from the Muslim electorate, but losing in the important Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab, Sindh, and Northwest Frontier Province. The Congress Party achieved a majority in nine of the eleven provinces.

Jinnah, who identified the Congress Party with the Hindu majority, offered it an alliance - both factions would face the British together, but the Congress Party would have to share power, accept the restoration of a separate electorate from the 1909 Constitution (suffrage), and respect the League as the representative body of Muslims in India. The latter two points were unacceptable to the Congress Party, which had its own national representatives of Islam and adhered to secularism. It refused to allow the Muslim League to hold offices and sinecures even in the provinces where significant Muslim minorities existed. Even as Jinnah entered into talks with Congress party president Rajendra Prasad, Congress members suspected Jinnah of using his position to make exaggerated demands and prevent the formation of a government, and demanded that the League merge with the Congress. Negotiations failed, and although Jinnah declared the withdrawal of all Congress members from provincial and central offices in 1938 to mark the day of his demise from Hindu dominance, some historians maintain that he continued to hope for an agreement.

In an address to the League in 1930, Sir Muhammad Iqbal raised the issue of an independent state for Muslims in north-west India. Rahmat Ali published a pamphlet in 1933 with the provocative title Now or never. Are we to live or perish forever? ("Now or never. Are we to live or perish forever?"), in which he promoted a state he called "Pakistan." Jinnah had initially given Rahmat Ali a sobering rejection. This, he said, was "an impossible dream". After the failure of cooperation with the Congress Party, the futile demand for restoration of a separate electoral franchise, and the Muslim League's demand for exclusive representation of the Muslim electorate, Jinnah swung to the idea of a separate state for Muslims as a means of preserving their rights. Jinnah came to believe that Muslims and Hindus were two separate nations with irreconcilable differences-a view that later became known as the "two-nation theory." He declared that a united India would lead to the marginalization of Muslims and later to a civil war between Hindus and Muslims. This change in his belief may have been caused by his correspondence with Iqbal, who was very close to Jinnah. During the party's convention in Lahore in 1940, the so-called Pakistan Resolution was adopted as the party's main objective. The resolution was rejected with an outcry of indignation by the Congress party and by many representatives of Muslims, such as Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi and the Jamaat-e-Islami. Jinnah was stabbed on 26 July 1943 and wounded in an attempted assassination by a member of the extremist Khaksars.

Jinnah founded the daily Dawn in 1941 - an important newspaper that helped him propagate the League's viewpoints. During the mission of British minister Stafford Cripps, Jinnah demanded parity regarding Congress Party and Muslim League ministers, as well as the League's exclusive right to represent Muslims and the right of Muslim-majority provinces to secede, which led to the breakdown of negotiations. Jinnah supported the British war effort during World War II and opposed the "Quit India" movement. During this period, the League formed provincial governments and joined the central government. After the death in 1942 of Union Muslim League leader Sikander Hyat Khan, a Muslim party that advocated Indian unity and opposed Pakistan's secession, the Muslim League's influence grew in Punjab. In 1944, Gandhi held 14 negotiations with Jinnah in Bombay for a united front; when the negotiations failed, Gandhi opened up to Jinnah about his support for the Muslims.

Establishment of Pakistan

In the 1946 elections to the Constituent Assembly of India, the Congress Party won most of the seats, especially those allotted to Hindus, while the Muslim League won the majority of Muslim seats. The British Cabinet Mission 1946 published a plan on May 16 calling for a united India consisting of handsome autonomous provinces and for "groups" of provinces to be formed on the basis of religions. A second plan, published on 16 June, envisaged the partition of India along religious dividing lines with the princely states able to choose between annexation to the Dominion or independence. The Congress Party, concerned about the fragmentation of India, criticized the proposal on May 16 and rejected it on June 16. Jinnah gave Muslim League approval to both plans knowing that power would be transferred only to the party that supported one plan. After debate, and against Gandhi's advice that both plans were divisive, the Congress party accepted the May 16 plan while rejecting the group principle. Jinnah condemned the acceptance as "dishonesty," accused the British negotiators of "treason," and withdrew the League's approval of both plans. The League boycotted the meeting, walked out of the Congress charged with forming the government, but disputed its legitimacy in the eyes of many Muslims.

Jinnah issued a call to all Muslims for Direct Action on August 16 to "reach out to Pakistan". Strikes and protests were planned, after which violence broke out all over India, especially in Calcutta as well as the district of Noakhali in Bengal, and more than 7,000 people were murdered in Bihar. Although Viceroy Archibald Wavell acknowledged that there was "no convincing evidence of this connection", League politicians were accused by the Congress Party and the media of orchestrating the violence. After a conference in London in December 1946, the Muslim League entered the interim government, but Jinnah did not relent in accepting office himself. It was credited as a major victory to Jinnah that the League entered the government even though it had rejected both plans and was allowed to appoint the same number of ministers despite being a minority party. The coalition was unable to work out of a growing sense within the Congress party that partition was the only way to avoid political chaos and possible civil war. The Congress Party agreed to the partition of Punjab and the partition of Bengal along religious lines towards the end of 1946. The new Viceroy Lord Louis Mountbatten and the Indian official V. P. Menon developed a proposal to create an Islamic Dominion in West Punjab, East Bengal, Balochistan and Sindh. After a heated and emotional debate, the Congress party endorsed this plan. In a referendum in July 1947, the North-West Frontier Province voted to join Pakistan. Jinnah asserted in a speech in Lahore on October 30, 1947, that the League had accepted partition because "the consequences of any other alternative would be too disastrous to imagine."

Governor General

Along with Liaquat Ali Khan and Abdur Rab Nishtar, Jinnah represented the Muslim League in the Partition Council, which had to divide public assets appropriately between India and Pakistan. Assembly members from the provinces that would form Pakistan made up the new Constituent Assembly, and British India's military had to be divided between Muslim and non-Muslim units and officers. Indian politicians were angered when Jinnah courted the princely states of Jodhpur, Bhopal, and Indore to join Pakistan, even though these princely states were not geographically connected to Pakistan and had Hindu-majority populations.

Jinnah became the first Governor General of Pakistan and President of its Constituent Assembly. Inaugurating the assembly on August 11, 1947, he put forward the vision of a secular state:

"They may belong to any religious caste or creed - this has nothing to do with the task of the state. In course of time Hindus will cease to be Hindus and Muslims will cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense because that is the personal profession of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state."

The office of governor-general was ceremonial, but Jinnah also claimed leadership of the government. The first months of Pakistan's existence were claimed by the intense violence that arose. As a result of hostilities between Hindus and Muslims, Jinnah agreed with Indian officials to organize a rapid and safe population exchange in Punjab and Bengal. He visited the border regions along with Indian politicians to pacify the people and establish peace, and organized huge refugee camps. Despite these efforts, estimates regarding the blood toll ranged from about 200,000 to 1 million people. The estimated number of refugees in both countries reached 15 million. The population of the capital Karachi exploded because of the large number of refugee camps. Jinnah was personally saddened and depressed by the intense violence of this period. To annex the princely state of Kalat and suppress the insurgency in Balochistan, Jinnah ordered violence. He accepted the controversial annexation of Junagadh, a Hindu-majority state with a Muslim ruler in the Saurashtra Peninsula about 400 kilometers southeast of Pakistan, but it was then reversed by Indian intervention.

It is unclear whether Jinnah planned or was aware of the tribal invasion of the Kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir from Pakistan in October 1947, but he dispatched his private secretary Khurshid Ahmed to monitor developments in Kashmir. When informed of Kashmir's annexation to India, Jinnah condemned the annexation as illegitimate and ordered the Pakistan Army's entry into Kashmir. Subsequently, the Commander-in-Chief of all British officers in the former colony of British India, Sir Claude Auchinleck, informed Jinnah that while India had the right to send troops into Kashmir, which had already reached it, Pakistan did not possess that right. If Jinnah continued to insist, Auchinleck would withdraw all British officers from both sides. Since Pakistan had a larger number of British in senior command positions, Jinnah countermanded his order but protested to the United Nations and demanded mediation.

Because of his role in the creation of the state, Jinnah was the most popular and influential politician. He played a crucial role in protecting minority rights, laying the foundations of the Pakistani state, establishing colleges, military institutions and Pakistan's fiscal policy. On his first visit to East Pakistan, Jinnah stressed that Urdu alone should be the national language, to which Bengalis in East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, strongly objected because they traditionally speak Bengali. He was working on an agreement with India to end disputes over wealth sharing.

Death

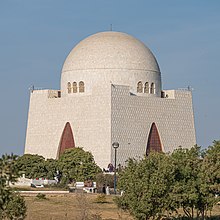

Throughout his life, Jinnah's lungs had been his weak point in health. Due to complications from pleurisy, Jinnah had been treated in Berlin long before the Second World War. Since then, frequent bouts of bronchitis had permanently limited his ability to serve and sapped his strength. Since June 1946 Jinnah knew the diagnosis of his doctor Dr. L. A. Patel: tuberculosis. Only his sister and a small number of close associates shared this secret. In 1948, Jinnah's health, due to the heavy burdens that followed the creation of Pakistan, began to falter. Attempting to recover and restore his health, he spent many months at his official retreat in Ziarat, but died on September 11, 1948, from a combination of tuberculosis and lung cancer. His burial was followed by the construction of a massive mausoleum - Mazar-e-Quaid - in Karachi to honour him; official and military ceremonies are held there on special occasions.

Jinnah's daughter Dina Wadia remained in India after Partition before ultimately relocating to New York City. Jinnah's grandson Nusli Wadia is a prominent industrialist living in Mumbai. In the 1963-1964 elections, Jinnah's sister Fatima Jinnah, known as Madar-e-Millat ("Mother of the Nation"), became the presidential candidate of a coalition of political parties in opposition to President Muhammed Ayub Khan, but she lost the election.

Jinnah's second wife Maryam, nicknamed "Ruttie".

The tomb of Mazar-e-Quaid Jinnah in Karachi

Criticism and heritage

Rating

Rajmohan Gandhi sees Jinnah as a supporter of the two-nation theory, according to which Hindus and Muslims cannot live together in the same state. In connection with the tug-of-war over Junagadh, he claims that Jinnah wanted to provoke India into demanding a plebiscite in Junagadh so that he could then demand a plebiscite in Kashmir himself. Jinnah had hoped that the Muslim majority in Kashmir would vote for annexation to Pakistan in the event of a plebiscite. Some historians like H. M. Seervai and Ayesha Jalal assert that Jinnah never wanted the partition of India - it was the result of the Congress Party leadership's unwillingness to share power with the Muslim League. It is alleged that Jinnah merely used the Pakistan issue as a method of mobilization to achieve significant political rights for Muslims.

Jinnah has won the admiration of major nationalist Indian politicians such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee. In June 2005, Lal Krishna Advani, party leader of India's Bharatiya Janata Party, paid a much-publicized visit to Jinnah's mausoleum in Karachi. He praised Jinnah's "secular" vision for the new state of Pakistan and lauded Jinnah as an "ambassador of unity between Hindus and Muslims." These words, unusual for a representative of Hindu nationalism, triggered fierce protests in Advani's party, forcing him to resign from the party presidency.

In Bangladesh, East Pakistan until the 1971 Liberation War, Jinnah is viewed negatively by some because, in their view, he concentrated power with West Pakistani (= non-Bengali) Punjabi industrialists and military officers. The Muslim population in Bengal did not agree that Bengali politicians were under-represented in the Muslim League leadership. This imbalance contributed to East Pakistan's later secession from Pakistan and independence as Bangladesh.

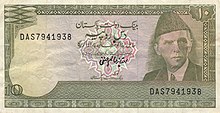

Honors

Jinnah is honored in Pakistan with the official title of Quaid-e-Azam ("Great Leader"). He is depicted on all Pakistani rupee banknotes with the value of ten or larger. To mark his 100th birthday, the government issued a postage stamp. Jinnah's mausoleum, the "Mazar-e-Quaid", is one of the most imposing buildings in Karachi.

Jinnah acts as a namesake for many public institutions in Pakistan. Among others are named after him:

- the Jinnah International Airport in Karachi (former name Quaid-e-Azam International Airport), the largest airport in Pakistan

- one of the biggest streets in the Turkish capital Ankara, the Cinnah Caddesi

- one of the most important expressways in the Iranian capital Tehran

Movies

In Richard Attenborough's film Gandhi (1982), Jinnah was mimed by theatre actor Alyque Padamsee. In the television mini-series Lord Mountbatten: the Last Viceroy (1986), Jinnah was played by Polish actor Vladek Sheybal. In the 1998 film Jinnah, he is portrayed as a young man by British actor Richard Lintern, and the older Jinnah by British actor Christopher Lee.

Jinnah House

Jinnah had had a stately residence built in Bombay in 1936, Jinnah House on a plot of land of one acre, officially known as South Court. The building is a Jinnah legacy of historical significance. It was here that Jinnah and Gandhi had held crucial talks on the partition of India in September 1944. Further talks between Jinnah and Jawaharlal Nehru took place on August 15, 1946 - a year to the day before India gained independence. Jinnah also felt a strong attachment to his house himself. When he became Governor General of Pakistan, he reportedly asked Indian Prime Minister Nehru to make the property available to the consulate of any country. Nehru offered Jinnah a lease, but it could not be finalized due to Jinnah's death. Thus, Jinnah's wish to be able to spend his twilight years at this place was also no longer fulfilled.

From 1948 to 1983, the building served the British High Commission as the residence of the Deputy High Commissioner. In 1983, the Government of India asserted its claims to the property. Since then, the Pakistani government has repeatedly asked India to sell or lease the building to it so that it could be used as the residence of the Pakistani embassy. India has not responded to this so far. Jinnah's only daughter Dina Wadia also lays claim to the property. In 2007, she filed a writ petition in the Mumbai High Court. The value of the property is estimated at around 400 million US dollars (as of 2017).

10 rupee banknote with the portrait of Ali Jinnah

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Muhammad Ali Jinnah?

A: Muhammad Ali Jinnah was the founder of the country of Pakistan.

Q: What was Jinnah's role in Pakistan after the partition of India?

A: After the partition of India, Jinnah became the Governor-General of Pakistan.

Q: What do Pakistanis call Jinnah as a mark of respect?

A: Pakistanis call Jinnah Quaid-e-Azam, which means "the great leader" in Urdu.

Q: What other phrase in Urdu is used to refer to Jinnah?

A: Another phrase in Urdu used to refer to Jinnah is Baba-e-Qaum, which means "the father of the nation".

Q: When is a national holiday celebrated in Pakistan in honor of Jinnah?

A: A national holiday called Pakistan day is celebrated in honor of Jinnah on the day of his birth.

Q: What is the meaning of the phrase Quaid-e-Azam?

A: Quaid-e-Azam means "the great leader" in Urdu.

Q: What is the meaning of the phrase Baba-e-Qaum?

A: Baba-e-Qaum means "the father of the nation" in Urdu.

Search within the encyclopedia