Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was a state that existed in the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1858. The heartland of the empire was in the Indus-Gangetic plain of northern India around the cities of Delhi, Agra, and Lahore. At the height of its power at the end of the 17th century, the Mughal Empire encompassed almost the entire subcontinent and parts of present-day Afghanistan. Between 100 and 150 million people lived in 3.2 million square kilometres. In 1700, its share of the world's population was estimated at about 29 percent.

The Muslim rulers are today referred to in German as "Mogul", "Großmogul" or "Mogulkaiser". Similar terms can also be found in other, mainly Western languages. In the state and court language Persian, which had replaced the original mother tongue of the Mughals - Chagataic, an Eastern Turkic language - the ruler's title was پادشاه pād(e)šāh (Padishah). It was comparable to the title of an emperor.

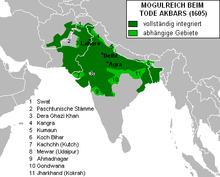

The first Great Mogul Babur (r. 1526-1530), a prince of the Timurid dynasty from Central Asia, conquered the Sultanate of Delhi, starting from the territory of the present-day states of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. Considered the most important Mughal ruler, Akbar I. (r. 1556-1605), who strengthened the empire militarily, politically and economically. Under Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), the Mughal empire experienced its greatest territorial expansion. However, it was so overstretched financially and militarily by the territorial expansion that it degraded to a regional power in the political structure of India in the course of the 18th century. Several heavy military defeats at the hands of the Marathians, Persians, Afghans, and British, as well as internal dynastic power struggles to gain dominion and the intensification of religious antagonisms at home between the Islamic "ruling caste" and the subjugated majority population of peasant Hindus, further favoured its decline. In 1858, the last Great Mogul of Delhi was deposed by the British. His territory was absorbed into British India.

Rich evidence of architecture, painting and poetry influenced by Persian and Indian artists has been preserved for posterity.

Gate of the Red Fort in Agra, capital of the Mughal Empire in the 16th and 17th century

To the name

The name "Mughal" as a designation for the rulers of northern India was probably coined in the 16th century by the Portuguese (Portuguese Grão Mogor or Grão Mogol "Great Mughal"), who established a Jesuit mission at Akbar's court as early as 1580, and later adopted by other European travelers in India. It derives from the Persian مغول mughul meaning "Mongol". Originally, "Mog(h)ulistan" referred to the Central Asian Chagatai Khanate. The latter was the homeland of Timur Lang, founder of the Timurid dynasty and direct ancestor of the first Mughal ruler Babur. Thus, while the name correctly refers to the Mongol descent of the Indian dynasty, it ignores the more precise relationship to the Mongol Empire. This is expressed in the Persian proper name گوركانى gūrkānī of the Mughals, which derives from the Mongol kürägän "son-in-law" - an allusion to Timur's marriage into Genghis Khan's family. Accordingly, the Persian name for the Mughal dynasty is گورکانیان Gūrkānīyān. However, in Urdu, the Mughal emperor is called مغل باد شاہ Mughal Bādšāh.

_2.jpg)

Le Grand Mogol ("The Grand Mogul"), fantasy painting by the French scholar Allain Manesson-Mallet from 1683

History

Previous story

Before the founding of the Mughal Empire, the Delhi Sultanate existed in northern India since 1206, which experienced the height of its power under Ala ud-Din Khalji (r. 1297-1316). Ala ud-Din subjugated large parts of the Deccan, at the same time repelling Mongol attacks from the northwest. Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq (r. 1325-1351) sought the complete incorporation of the central and southern Indian empires. His plan, however, failed, and by shifting the capital from Delhi to Daulatabad on the Deccan, he weakened the sultans' position of power in the north Indian plains. The decline of the empire began, culminating in the conquest and sack of Delhi by Timur in 1398. Although Timur quickly retreated, the sultanate never fully recovered from the devastating consequences of the defeat. All provinces gained their independence, so that the sultanate was now limited to the surroundings of Delhi. Even a temporary expansion under the Lodi dynasty (1451-1526) could not restore the former size and power of the empire.

1504-1530: Emergence under Babur

The Delhi Sultanate finally came to an end in 1526, when Zahir ud-Din Muhammad, called Babur (Persian "Beaver"), defeated the last sultan. Babur hailed from Fergana, now Uzbekistan, one of the many Muslim petty principalities of Transoxania ruled by the Timurids. Babur was a direct sixth-generation descendant of Timur on his father's side, and his mother even traced her lineage directly back to Genghis Khan. After inheriting his father's estate in Fergana and twice briefly gaining possession of Samarkand, he was forced to flee his homeland in 1504 before the strengthening Uzbeks under Shaibani Khan. He retired to Kabul, which he henceforth ruled as a kingdom. Since the extinction of the last other remaining Timurid court in Herat in 1507, he held the title of padeshah (emperor), formally superior to a shah (king), and thus claimed the leadership position among the Timurid princes. From Kabul, he made initial exploratory forays into northwestern India (into what is now Pakistan) via the Chaiber Pass, but then allied himself with the shah of Safavid Persia, Ismail I, in order to regain Samarkand, which he actually captured but was unable to hold. In return for the Shah's support, he had to publicly profess Shiite Islam, but later returned to the Sunni faith, of which he was probably also inwardly convinced. This is also supported by the fact that Babur raised his son Humayun in the Sunni faith. The renewed failure of the Samarkand enterprise seemed to have finally ripened the decision to turn to India, especially since Babur, thanks to his ancestor Timur, could lay claim to the possessions of the Delhi Sultan. The latter, however, refused to submit to Babur.

In preparation for his Indian campaign, Babur introduced cannons and guns on the Ottoman model, which had never before been used in a field battle in northern India. In 1522 Kandahar fell, and by early 1526 he had extended his rule far into the Punjab. There, on April 20 of the same year, came the decisive clash with the vastly outnumbered army of Sultan Ibrahim II : the use of firearms, the high mobility of mounted archers on the flanks, and defensive tactics inspired by the Ottoman army helped Babur to a superior victory over the last Delhi sultan at the Battle of Panipat. After occupying Delhi and Araga, which had been made the capital of the Lodi dynasty two decades earlier, he proclaimed himself emperor of Hindustan, thus establishing the Mughal Empire.

Nevertheless, Babur's rule was far from being consolidated, for a new enemy had arisen in the Rajput prince Rana Sanga of Mewar. The latter sought to restore Hindu rule in northern India and had formed a confederacy with other Rajput rulers for this purpose. Babur had to persuade his soldiers, whom it urged to return to Kabul, to stay with generous rewards from the treasury of the defeated sultan. It was only with the victory over the Rajput confederacy on March 17, 1527, at the Battle of Khanua that his rule in Hindustan was reasonably secure.

Babur subsequently travelled extensively throughout his new empire, quelling several revolts and distributing generous gifts to his subjects and relatives, which placed a heavy burden on the state treasury. He was resolutely liberal and conciliatory towards his subjects, but retained virtually unchanged the administrative structures of the Lodi dynasty, which were based on the granting of jagir (fiefs) and thus local loyalties. In 1530, Babur's son Humayun inherited an internally fragile empire that stretched from the Hindu Kush to Bihar.

1530-1556: Humayun's reign and Surid interregnum

Humayun's time was marked by setbacks that temporarily deprived the emperor of control over his empire and nearly ended Mughal rule in India after less than 15 years. According to Timurid tradition, all legitimate sons of a ruler were entitled to succeed to the throne. Humayun, who was considered pliant and superstitious, even childish at times, therefore found himself embroiled in disputes with his half-brothers. In addition, there were external threats. In the southwest, Sultan Bahadur of Gujarat was expanding, while in Bihar in the east, Sher Khan Suri was preparing a rebellion as the leader of a group of Pashtuns who had entered military service with the Lodi dynasty. Both had failed to swear allegiance to Humayun after his accession to the throne.

Humayun, who preferred to devote himself to planning a new capital, did not decide to launch a campaign against Gujarat until 1535, which was initially successful. The outbreak of Sher Khan's rebellion in Bihar forced him to return to Agra and abandon the conquered territories. In 1537 he moved against Sher Khan, who sacked the Bengal capital of Gaur before the encounter and henceforth called himself Sher Shah. At Chausa, east of Varanasi, in 1539, Humayun was defeated by Sher Shah, who had at first agreed to the retreat of his army, but then raided Humayun's camp by night and drove its soldiers into the Ganges, where most of them drowned. Humayun nearly perished himself in the process had not a servant saved his life. Meanwhile, his half-brother Hindal had tried unsuccessfully to usurp the throne. Nevertheless, the sibling quarrel divided and demoralized Humayun's forces. The Battle of Kannauj in 1540 sealed Hindustan's loss. Humayun fled into exile in Persia, to the court of Tahmasp I. Only with the help of a Persian army was he able to regain Kabul in 1545.

Sher Shah founded the short-lived Surid dynasty as Sultan of Delhi. Extensive reforms in the areas of administration and finance were intended to consolidate the rule, but a succession dispute plunged the Surids into chaos in 1554, thus enabling Humayun's return to India a year later. Building on Sher Shah's reforms, Humayun planned to establish a new administrative system. His sudden death in 1556 prevented this project.

1556-1605: Consolidation by Akbar

Humayun's eldest son Akbar was undisputed within the dynasty, but his empire was threatened by the Surid descendants. Taking advantage of their discord and the weakness of the newly restored Mughal empire, the Hindu Surid general Hemu arbitrarily occupied Delhi and proclaimed himself Raja in October 1556, but was defeated by Akbar's army in the Second Battle of Panipat on November 5. Within a year, the remaining Surids were also finally defeated. The Mughal Empire was thus militarily secured for the time being.

By means of numerous campaigns and political marriages, Akbar enlarged the empire considerably. In 1561, the central Indian sultanate of Malwa was subjugated. In 1564 Gondwana fell, in 1573 Gujarat and in 1574 Bihar. Bengal was administered by Suleiman Karrani for Akbar. After his death there were revolts, which Akbar suppressed in 1576. The territories were now formally annexed to the Mughal Empire and placed under provincial governors. Of great importance was the subjugation of the militarily strong Rajput states, whose full integration had never before been achieved by any Islamic empire. Through a skilful marriage policy, Akbar gradually weakened the Rajputs. At the same time, he took military action against the princes who were hostile to him. In 1568, Mughal troops captured the strongest Rajput stronghold of Chittor after several months of siege and massacred the civilian population. Within a few years, all Rajput princes except the Rana of Udaipur had finally recognized the supremacy of the Mughal Empire. The Rajputs thereafter constituted an important pillar of the army, at least until Aurangzeb turned them against him with his intolerant policies.

In addition to his conquests, Akbar was the first Mughal ruler to devote himself extensively to the internal consolidation of the empire. One of the most important foundations was religious tolerance towards the Hindu majority of the empire's population. Although there had been cooperation between the two faith groups under previous Muslim rulers in the Indian subcontinent as well, the extent of religious reconciliation under Akbar went far beyond that of previous rulers. For example, more Hindus entered government service under Akbar than ever before, and special taxes on non-Muslims were abolished. Akbar himself moved further and further away from orthodox Islam, even proclaiming a religion of his own called din-i ilahi ("Divine Faith"). He also continued the reform of provincial administration and tax collection begun by Sher Shah, largely replacing the feudal system still in use under Babur with a more rational, centralized civil service. In the social sphere, Akbar sought, among other things, to abolish child marriages and widow burnings (sati), to standardize units of measurement, and to improve the educational system. However, many of his modern ideas had only limited effect due to widespread corruption.

Akbar's policy of religious tolerance and departure from orthodox Sunni Islam prompted some conservative religious scholars to call on his half-brother Hakim to rebel in Kabul. The Mughal Empire found itself in a threatening position, as Hakim received succor from the Pashtuns living in Bengal, who had once already supported Sher Shah and were now breaking up a rebellion. In the summer of 1581 Akbar entered Kabul and crushed Hakim's rebellion, thus restoring the unity of the empire. The pacification of the western and eastern provinces was followed by the conquest of the Kashmir Valley in 1586, Sindh in 1591/92, and Orissa in 1592/93. Thus the entire North Indian Plains and large parts of the present-day states of Afghanistan and Pakistan were under the control of the Mughal Empire, which had natural frontiers in the form of the Himalayas in the north and the fringing mountains of the Deccan highlands in the south. In the west and northwest, Akbar secured the empire through a balanced foreign policy that pitted Persia and the Uzbeks against each other.

From 1593 Akbar undertook several campaigns to conquer the Deccan, but with only moderate success. Thus, although the Shiite Deccan Sultanate of Ahmadnagar was defeated in 1600, it was not fully integrated. After Akbar's death in 1605, it temporarily regained its independence.

Nevertheless, Akbar's rule had consolidated the Mughal Empire internally and externally to such an extent that it was able to rise to become the undisputed supreme power of South Asia. Akbar's centralized administrative system made the Mughal Empire one of the most modern states of the early modern period. No previous empire in Indian history was able to administer such a large territory permanently and effectively, although the ancient Maurya Empire under Ashoka and the medieval Delhi Sultanate under the Tughluq dynasty surpassed Akbar's Mughal Empire in size.

1605-1627: Phase of relative peace under Jahangir

Akbar's eldest son Selim ascended the throne in 1605 under the name Jahangir (Persian for "conqueror of the world"). Under him, the Mughal Empire experienced a period of relative peace, which contributed to its further consolidation. A decisive part in this was played by Jahangir's wife Nur Jahan and her family, who increasingly exerted influence on imperial politics. Jahangir's son Khurram, who later succeeded him as Shah Jahan, also attained an important position of power at court during his father's lifetime. Akbar's liberal policies were continued, including the softening of inheritance laws and improved protection of property. In addition, Jahangir's reign was, according to the inclinations of the ruler, a phase of pronounced artistic creation.

In 1614, the final pacification of Rajputana was achieved by subjugating the last still independent Rajput state of Udaipur (Mewar). Khurram, who had been entrusted by Jahangir with the campaign against Udaipur, ravaged and plundered the lands of the Rana of Udaipur and finally forced the latter to pledge allegiance to the Mughal Empire through diplomatic negotiations. Among the few military conquests, the Himalayan principality of Kangra (1620) was the most significant. In contrast, the attempts made from 1616 onwards to move the frontier southwards on the Deccan were less successful. Above all, the guerrilla-like tactics of the commander Malik Ambar, who was in the service of Ahmadnagar, prevented the expansion of the Mughal Empire on the Deccan.

In the last years of Jahangir's reign, a power struggle between the unofficial ruler Nur Jahan and Khurram, who by this time was already calling himself Shah Jahan (Persian for "King of the World"), led to unrest. When Kandahar was threatened by the forces of the Persian Shah Abbas I in 1622, Shah Jahan entered into rebellion with an army he commanded on the Deccan. The deployment of the Mughal army against him denuded Kandahar, which soon fell to Persia. Shah Jahan's rebellion lasted for four years.

After Jahangir's death in 1627, the vizier Asaf Khan deposed Nur Jahan and helped Shah Jahan to the throne by having all other pretenders to the throne assassinated.

1628-1658: Cultural flourishing under Shah Jahan/Schahdschahan

Shah Jahan is considered the most glamorous Mughal ruler, under whose reign the court reached the height of its splendor and the architecture in the Indian-Islamic mixed style reached its highest flowering. The most famous Mogul building, the Taj Mahal in Agra, was built as a tomb for Shah Jahan's wife Mumtaz Mahal, as were a number of other outstanding architectural monuments. However, Shah Jahan's patronage of the arts placed a heavy burden on the state coffers. Inflation could only be kept in check with difficulty, and higher taxes on crop yields triggered a rural exodus.

Costly military failures also had a negative impact on the economy of the empire. Although the war on the Deccan, which had already been waged since Akbar, showed its first tangible successes - in 1633 Ahmadnagar was defeated and finally annexed, in 1636 Golkonda submitted, albeit only symbolically, and in the same year the second Deccan sultanate Bijapur, which now still existed, was forced by treaty to pay tribute - the initial victories were followed by a series of setbacks. In 1646, unrest in Transoxania prompted Shah Jahan to campaign against the Uzbeks in order to regain the ancestral homeland of the Mughals, in particular Samarkand, which his ancestor Babur had been able to occupy three times for a short time. The campaign ended in defeat a year later. In addition, a dispute with Persia ignited over the important trading city of Kandahar, which had been restored to the possession of the Mughal Empire in 1638 through high-handed negotiations between the Persian governor and the Mughals. In 1649, Kandahar again fell to Persia. Three successive sieges did not change this, mainly because Persian artillery was superior to Mughal. Persia increasingly became a threat to the Mughal Empire, especially since its Shi'ite neighbor was on friendly terms with the Deccan Sultanates, who were also Shi'ite. Persia's antagonism and the associated decline in Persian influence at the Mughal court may also have been a reason for the Sunni ulama's rise to power in the Mughal Empire, although Akbar's and Jahangir's principle of religious tolerance was not entirely eroded.

The rivalry between Shah Jahan's sons Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh for the succession to the throne marked the last years of his reign. Dara Shikoh prevented progress on the Deccan through intrigue, where Aurangzeb moved against Golkonda in 1656 and Bijapur in 1657. When Shah Jahan fell seriously ill in late 1657, his sons Shah Shuja - governor of Bengal - and Murad Bakhsh - governor of Gujarat - each proclaimed themselves emperor to prevent a possible seizure of power by their eldest brother Dara Shikoh. Aurangzeb, meanwhile, was able to convince Murad to let him have his army to march against Delhi with combined forces. Shah Shuja was defeated by Dara Shikoh at Varanasi in February 1658, and the latter was defeated by Aurangzeb near Agra on 29 May 1658. At Agra, Aurangzeb captured his father, who died in prison in 1666. After Aurangzeb had his brother Murad also arrested, he proclaimed himself emperor in the same year.

1658-1707: Southern expansion and incipient decline under Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb's reign was characterized by two opposing tendencies: on the one hand, he expanded the Mughal empire far to the south to cover almost the entire Indian subcontinent; on the other hand, he shook the economic foundation of the Mughal empire through continuous wars. With a policy of religious intolerance, he damaged the symbiosis of Muslim elite and Hindu subjects that his predecessors had fostered. Already the last third of his reign was determined by the struggle against the threatening decline of the empire.

Aurangzeb consolidated his rule by executing his brothers and rivals Dara Shikoh and Murad Bakhsh. His third brother and adversary, Shah Shuja, fled into exile in Arakan after being militarily defeated by Aurangzeb, and was tortured to death there in 1660 along with his family and some of his retinue. Islam served as Aurangzeb's legitimation for rule, and unlike his predecessors, he applied its laws strictly to the empire. The most drastic measures were the reintroduction of the poll tax for non-Muslims (jizya), which Akbar had abolished in 1564, and the prohibition of new construction of Hindu temples and places of worship of other faiths in 1679. Throughout the country, numerous temples built shortly before were destroyed. Aurangzeb's theocratic policies created tensions between Hindus and Muslims that severely disturbed the internal peace of the Mughal Empire and aroused the opposition of Hindu princely houses. Thus, the invasion of the Hindu Rajput state of Marwar in 1679, whose ruler had died without an heir, sparked unrest among the Rajputs that simmered until Aurangzeb's death.

On the Deccan a third strong enemy had arisen for the Mughal Empire besides Bijapur and Golkonda. The Hindu Shivaji had been able to unite the Marathi tribes under his leadership since the middle of the 17th century and was busy building a Hindu state. Shivaji, like Malik Ambar half a century earlier, employed guerrilla tactics and also made extremely successful use of diplomacy to play off his neighbours, including the Mughals, against each other. In 1664, he had even succeeded in pillaging the Mughal Empire's most important port city, Surat. During a visit to Aurangzeb's court, he was captured but managed to escape and establish an empire on the western Deccan. In 1681, Aurangzeb's renegade son Akbar formed an alliance with Sambhaji, Shivaji's successor. This prompted Aurangzeb to concentrate all his forces on the conquest of the Deccan. For this purpose, he shifted the capital and thus the centre of gravity of the empire to Aurangabad. The Deccan campaign was initially extremely successful, with the fall of Bijapur in 1686 and Golkonda a year later. Both states were incorporated into the Mughal Empire, which now encompassed the entire subcontinent except for the Malabar coast and the areas south of the Kaveri. In 1689, control of the Deccan seemed finally secured with the capture and execution of Sambhaji. In fact, however, the Maraths had not been defeated, but merely fragmented into smaller factions. Shivaji had stimulated a new spirit of resistance that could not be broken by individual military victories. Aurangzeb spent the rest of his life on the Deccan fighting Marathi tribal leaders. Meanwhile, his authority in Hindustan, the very heartland of the Mughal Empire, was noticeably waning. However, uprisings such as those of the Jats in the Delhi and Agra area and of the Sikhs in the Punjab were also the result of crushing taxes that had become necessary to finance the war campaigns.

Aurangzeb made the same mistake as Muhammad bin Tughluq in the 14th century by neglecting his power base in the north, thus disrupting the administration. The empire became overstretched and financially overburdened by expansion into the rugged, difficult-to-control Deccan, which also yielded far lower tax revenues than the fertile plains of the north. Only Aurangzeb's personal authority still held the empire together, while the emperor distrusted and even suppressed capable leaders - such as those possessed by previous rulers in the form of generals, ministers, or kinsmen.

1707–1858: Decline and fall

After Aurangzeb died in 1707, his son Bahadur Shah became head of the state. He made peace with the Maraths and recognized their dominion in the western Deccan so that he could use the Mughal army to suppress the Sikh rebellion in the north. The renegade Rajputs, however, were getting increasingly out of control. His ambitious attempts to consolidate the empire once again through comprehensive reforms, following Akbar's example, failed due to the already advanced decay of the administrative structures. Many official posts had become hereditary, including the office of governor of Bengal, which made tax collection difficult. Bahadur Shah, who had ascended the throne at an advanced age, died in 1712 after only five years of rule.

Bahadur Shah's successors failed to maintain imperial authority. His son Jahandar Shah was assassinated after only a few months on the throne. Responsible for the assassination were the Sayyids, two brothers who served as commanders at the Mughal court and rose to become a major power factor at court in the years that followed. Farrukh Siyar ruled merely as a puppet of the Sayyids, who were allied with the Maraths. During his reign 1713-1719, the British East India Company, which had established itself as the leading European trading company on the Indian coast during the 17th century, obtained extensive concessions in the lucrative Indian trade. However, the improvement in the financial situation hoped for by stimulating foreign trade failed to materialize, as the British knew how to exploit the increasing economic dependence of the Mughals on the maritime trade of the Europeans. The provinces of the Mughal Empire could also only be held by concessions that turned them into semi-autonomous states.

In 1719, the Sayyids also had Farrukh Siyar killed, who proved unable to restore the empire to its former strength. A bloody power struggle ensued, from which Muhammad Shah (r. 1719-1748) emerged victorious. He had the Sayyids executed, but otherwise left power to the other interest groups that had formed at the imperial court since Bahadur Shah. Administration was limited to the appointment of governors, whose provinces were only nominally under the emperor. In 1724, Muhammad Shah's vizier Asaf Jah I resigned. He de facto detached his province of Deccan from the imperial union and ruled it as the Nizam of Hyderabad. With this, the empire lost one-third of its state revenue as well as nearly three-fourths of its war material.

The weakness of the empire was taken advantage of by the Afsharid ruler of Persia, Nadir Shah. He defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Karnal north of Delhi in 1739, not far from the historic battlefields of Panipat, and after an agreement moved peacefully into Delhi. When a rebellion broke out against him, he ordered a massacre, looted the entire city, including the Mughal treasury, and returned to Persia. Thus he had finally dealt a death blow to the Mughal Empire: The process of "regionalization of power" that had begun earlier now continued apace, and soon confined the actual domain of the Mughals only to the region around Delhi and Agra. Bengal and Avadh gained de facto independence, even though they formally recognized the suzerainty of the Mughal emperor and paid symbolic tribute. The Persian frontier was moved to the Indus. At the same time, the Maraths expanded into Malwa and Gujarat.

The Mughal Empire won its last military victory in 1748 at Sirhind, northwest of Delhi, over the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Durrani, but Muhammad Shah died a few days later, and his weak successors had nothing more to offer the Afghans. The latter annexed the Punjab, Sindh and Gujarat. In 1757 they sacked Delhi. In the same year, the British East India Company defeated the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey and forced him to cede the territory around Calcutta. This marked the beginning of British territorial rule in India, which in the following years was extended to the whole of Bengal and, after the victory at the Battle of Baksar in 1764, to Bihar as well. The British, expanding from the east into formerly Mughal territory, had become a serious threat to the Mughal Empire. The Maraths too were rapidly advancing further and further north, but were defeated by the Afghans in the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761.

It was not until 1772 that the Great Mogul Shah Alam II (r. 1759-1806), in exile in Allahabad during the Afghan-Marathi War, was able to return to Delhi with Marathi support. Blinded by marauding Afghans in 1788 under Ghulam Qadir, he was forced to accept as a protecting power in 1803 the British East India Company, which had already imposed a treaty of protection on Avadh two years earlier. Though the Great Mughal still formally possessed rulership, the real power now rested with the British Resident. The Mughal territory was limited to the Red Fort of Delhi.

In 1858, the nominal rule of the Great Mughals also ended after the British put down the Great Revolt that had broken out the year before. Bahadur Shah II (r. 1838-1858), whom the rebellious soldiers had proclaimed the symbolic leader of the mutiny against his will, was found guilty of complicity in the revolt by a court martial in March 1858, deposed, and exiled to Rangoon in the British-occupied part of Burma, where he died in 1862. His territory, along with all other territories under the direct control of the British East India Company, was transferred to the newly formed colony of British India on August 2, 1858, effective November 1. The British Queen Victoria assumed the title of Empress of India in 1876 in continuation of the Mughal rule.

Studio portrait of a mogul with his children in Delhi by Sheperd and Robertson, c. 1860s.

Bahadur Shah II at the age of 82 shortly before his condemnation in Delhi in 1858. Photograph by Robert Christopher Tytler, possibly the only one ever taken of a Mughal emperor.

The Emperor of the Mughal Empire Shah Alam II, as a prisoner British East India Company, 1781.

Muhammad Shah (r. 1719-1748), miniature, c. 1720-1730

The Mughal Empire around 1700 under Aurangzeb

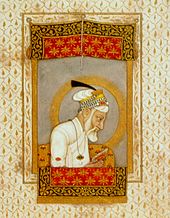

Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) in old age reading the Koran (miniature, 18th century)

Shah Jahan (r. 1627-1657/58) during a darbar (audience) in the audience hall of his palace (miniature painting c. 1650)

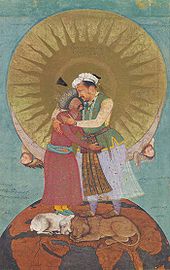

Jahangir (r.) and Shah Abbas I of Persia (painting by Abu al-Hasan, c. 1620)

Expansion of the Mughal Empire on the death of Akbar (1605)

Expansion of the Delhi Sultanate at the beginning of 1526 and Babur's India campaign

Akbar (r. 1556-1605) on a drawing (around 1605)

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Mughal Empire?

A: The Mughal Empire was a Sunni Islamic empire in South Asia that existed from 1526 to 1858.

Q: What did the Mughal Empire rule over?

A: The Mughal Empire ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent, and parts of what is now India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar between 1526 and 1707.

Q: How large was the Mughal Empire's economy?

A: The Mughal Empire had the world's largest economy at 25% of the world's GDP.

Q: What kind of impact did the Mughal Empire have on its area?

A: The Mughal Empire signalled proto-industrialization and had a lavish architecture.

Q: When did the Mughal Empire exist?

A: The Mughal Empire existed from 1526 to 1858.

Search within the encyclopedia