Moscow Kremlin

![]()

Kremlin is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Kremlin (disambiguation).

p1

p3

The Moscow Kremlin (Russian Московский Кремль; scientific transliteration Moskovskij Kremlʹ) is the oldest part of the Russian capital Moscow and its historical center. The original medieval castle on the Moskva River was rebuilt as a citadel from the late 15th century. It served as a residence for the Grand Princes of Moscow until the 16th century, and then for the Russian tsars until the capital was moved to Saint Petersburg in the early 18th century. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the Kremlin was also the seat of the metropolitans and later patriarchs of Moscow. After the October Revolution in 1918 it once again became the centre of state power: initially the seat of the Soviet government, it has been the official residence of the President of the Russian Federation since 1992. The name "Kremlin" is therefore also used as a synonym for the entire Soviet or Russian leadership.

A characteristic feature of the architectural ensemble of the Moscow Kremlin is its fortification complex, which consists of a triangular boundary wall with 20 towers. It was largely built between 1485 and 1499 and is still well preserved today. After its completion, it served several times as a model for similar fortresses built in other Russian cities. Within the Kremlin walls are numerous sacred and secular buildings - cathedrals, palaces and administrative buildings - from different eras. Last but not least, the Kremlin is a museum and, as Russia's political and former religious centre, was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1990. Together with the neighbouring Red Square, which is also on this list, the Kremlin is generally regarded as Moscow's most important sight.

The Moskva and the Kremlin at dusk (2007)

The Kremlin with the Great Moskva Bridge (around 1890)

General description

Geography and transport

The 27.5-hectare site of the Kremlin is located on the approximately 25-metre-high Borovitsky Hill on the left bank of the Moskva, a river from the Volga catchment area that is around 120 metres wide in this area. Immediately west of the Kremlin, the small Neglinnaya River, whose riverbed has been in a continuous underground channel since the beginning of the 19th century, flows into the Moskva. Previously, the Neglinnaya flowed along the western section of the Kremlin wall (exactly where the green spaces of the Alexander Garden are located today) and thus constituted one of the two natural bodies of water that washed around the Kremlin and in this way provided additional protection against possible raids. A few hundred meters further downstream - already far from the Kremlin walls - lies the mouth of the Yausa, another Moskva tributary.

Borovitsky Hill, often referred to simply as Kremlin Hill, is a natural elevation that probably takes its name from the Old Russian word bor meaning "coniferous forest". It is one of the seven hills on which the present-day Moscow city center was built. At the time of Moscow's founding, it had a particularly good strategic location for building a city: It was washed by rivers on two sides and, due to its elevated position, offered its inhabitants not only relatively high security from attackers, but also good protection from floods, which were quite frequent in Moscow before the construction of the water diversion canal at the end of the 18th century. Geographically, Borovitsky Hill is one of the numerous elevations of the East European Plain, in the area of which the entire city area is located.

Today's Kremlin area has the approximate shape of a triangle. The south side of the Kremlin faces the banks of the Moskva River, while the west side was once surrounded by the Neglinnaya River and today borders the Alexander Garden. Adjacent to the eastern and northeastern sections of the Kremlin wall is the historic Kitai-Gorod district, whose central square is known as Red Square and, along with the Kremlin, is one of Moscow's two main tourist attractions. It stretches parallel to the Kremlin wall for almost the entire eastern section.

The Kremlin is located in the heart of Moscow's historic centre and was the geographical centre of the city until July 1, 2012, when the city's territory more than doubled due to the incorporation of the new administrative districts of Novomoskovsky and Troitsk. The Kremlin is the starting point of all major radial roads leading from the center of Moscow in several directions. Looking at the Kremlin on the Moscow city map, one can see its position as the core of Moscow's basic urban structure, which is a comparatively symmetrical, "cobweb-like" interconnection of several major ring and radial roads. The former are the Boulevard Ring, which is not completely closed and circles the Kremlin about a kilometre from its walls, the Garden Ring, which runs a good kilometre further out, and the three Moscow Ring roads (the Third Ring Road, the Fourth Ring Road, which has not yet been completely built, and finally the MKAD Ring, which largely coincides with the city boundary). The most important radial roads, which have their starting point in front of the Kremlin walls, include Tverskaya Street beginning at Red Square (which out of the city merges into the M10 trunk road to Tver and St. Petersburg), Vosdvishka Street, which begins immediately to the west of the Kremlin (about 500 meters further west it becomes New Arbat and out of the city it becomes the M1 highway to Smolensk, Minsk, and Warsaw), and M3 Street, which begins in front of the southwestern corner of the Kremlin walls and leads to Kaluga, Bryansk, and Kiev.

In addition to a road junction, there are a large number of public transport stops and stations in the immediate vicinity of the Kremlin. For example, in front of the Kutafya Tower alone, now the main entrance to the Kremlin, are the entrances to four stations of the Moscow Metro, and another eight metro stations are also within walking distance of the Kremlin and Red Square.

Structure

The ensemble of the Moscow Kremlin consists on the one hand of the fortification complex, which includes the walls and watchtowers dating from the late 15th century, and on the other hand of the totality of buildings, monuments, streets and squares within these fortification walls.

Fortifications

See also: Wall and towers of the Moscow Kremlin

The dark red brick Kremlin wall is 2235 meters long along its entire course. Depending on the topographical conditions, it has a height of 5 to 19 meters without taking into account the towers built into it and is at least 3.5 meters thick; in individual places, which were considered particularly vulnerable to attack in the Middle Ages, the thickness of the Kremlin wall is up to 6.5 meters. In addition to the wall itself, the 20 Kremlin towers are part of the citadel's fortification complex. With the exception of the Tsar Tower, which was erected only in 1680 for purely decorative purposes, all the towers were built at the same time as the wall. When they were built, they had a purely defensive function, and only in the 17th century, when the Kremlin's importance as a fortress gradually declined, were they raised for representational purposes and given their characteristic tent roofs and spires. All 20 Kremlin towers are different in shape and height, although there are several towers that look very similar when compared superficially. The tallest tower is the Trinity Tower, located in the central area of the western section of the wall, which has a height of 80 metres, including the spire and the red star crowning it.

Four Kremlin towers have passage gates in their base part, through which the entrance or entry to the Kremlin is made today. These are the Borovitsky Tower and the Trinity Tower on the western section of the wall, and the Nicholas Tower and the Savior Tower on the side facing Red Square. Visitors can enter and leave the Kremlin through the former two gates, while the two entrances located on Red Square are currently reserved for the staff of the Kremlin-based authorities and the soldiers of the Kremlin garrison.

Inner structure

Since its construction at the end of the 15th century, the area of the present Kremlin, surrounded by the fortress wall, has had its approximately triangular shape with the three peaks facing north, southwest and southeast.

Some of the buildings on the territory of the Kremlin stand directly on the Kremlin wall or are even - as the Arsenal - attached to it. Only the southern section of the wall, which stretches along the Moskva River, does not have any additional buildings today. There, on the slopes from the hilltop to the bank, stretches the so-called Secret Corridor Garden (Тайницкий сад), the largest green space on the Kremlin grounds, named after one of the watchtowers on the southern section of the wall. Part of the upper section of this garden, developed as a decorative park, is open to the public, while the areas immediately adjacent to the Kremlin wall are currently used exclusively for official purposes. There are also some small economic and administrative buildings there, which have no architectural conservation value and therefore do not belong to the Kremlin ensemble proper.

A large part of the Kremlin buildings are located a little further behind the walls and are separated by streets and squares, which have their own names similar to all other Moscow streets and squares. The most famous squares in the Kremlin include the two squares accessible to tourists: Ivan Square and Cathedral Square (Russian: Ивановская площадь and Соборная площадь, respectively). The former, named after the church of St. John (Ivan) Klimakos that once stood here, is best known for its historical significance: From the 14th to the 17th centuries it was Moscow's largest and most important square for gatherings and popular festivals; among other things, tsarist decrees were proclaimed to the people here. The Cathedral Square is famous for its self-contained architectural ensemble: The five surviving ecclesiastical buildings of the Kremlin are located here: the Cathedral of the Assumption, the Archangel Michael Cathedral, the Cathedral of the Annunciation, the Church of the Laying Down of the Robe of the Virgin Mary, and the Ivan the Great Bell Tower. Geographically, the Cathedral Square is also the center of the Kremlin compound as well as the highest point of the Kremlin hill.

The network of roads within the Kremlin essentially comprises four main streets connecting the core of the fortress, including Ivan Square and Cathedral Square with their passage gates. Borovitsky Street (Russian: Боровицкая улица) leads from the gate of Borovitsky Tower along the Secret Corridor Garden, past the Armory and the main building of the Great Kremlin Palace, to Ivan Square. There it merges into Redeemer Street (Спасская улица), which connects Ivan Square with the Redeemer Tower and, by extension, Red Square. In the northern direction, Nicholas Street (Никольская улица) branches off from Ivan Square to Nicholas Tower; on it, facing each other, are the two 18th-century buildings of the Arsenal and the Senate Palace, as well as the small Senate Square named after the latter (Сенатская площадь). To the west, Ivan Square ends at the Trinity Tower. Borovitsky Street connects it and the Trinity Tower with another street, named Palace Street (Дворцовая улица) after the Great Kremlin Palace located near it. The square at the intersection of Palace and Borovitsky Streets, closed off from the south by a cast-iron fence, is sometimes called Palace Square (Дворцовая площадь) or Emperor Square (Императорская площадь).

Accessibility for tourists

Since the Moscow Kremlin became accessible to the public again in the mid-20th century after a thirty-year hiatus, it has fulfilled two key functions at the same time: On the one hand, it is the official residence of the Russian president (or was until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the seat of the Soviet government), but on the other hand it is an open-air museum and a tourist attraction. Due to its function as the presidential seat, the Kremlin is a specially secured area that is accessible to the public only with certain restrictions - in contrast to the Red Square, the Alexander Garden and other outdoor areas. Tourists can enter the Kremlin through the two entrances at Kutafya Tower and Borovitsky Tower, and must pass through a security checkpoint. Larger bags and backpacks may not be taken into Kremlin territory. Admission to the Kremlin is subject to a fee; a regular ticket costs 500 rubles (as of November 2015; the equivalent of about seven euros); discounted tickets are also available, e.g. for schoolchildren, students or pensioners. To visit the Armoury and the exhibitions in the Patriarchal Palace, a separate ticket must be purchased.

Within the Kremlin, a number of areas are generally inaccessible to the public. This applies in particular to the building complex around the Senate Palace, which is part of the President's official residence, but also to Palace Street, where the Kremlin Command is based. A number of structures - including the Senate Palace, the Arsenal and all Kremlin towers - are also currently closed and can only be visited from the outside. The security of the Kremlin and the surrounding areas is the responsibility of the Kremlin Command and the FSO, the domestic intelligence service responsible for the personal protection of the president. Under its aegis is also the Kremlin garrison located in the Arsenal building, sometimes referred to as the presidential or Kremlin regiment (Russian: Кремлёвский полк). Besides guarding the Kremlin objects, it additionally fulfills purely representative purposes: its soldiers keep honor guard at the War Memorial with the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Alexander Garden and accompany important state ceremonies with solemn marches. The regiment also includes a cavalry unit, which in the summer months regularly organizes guard relief shows on the Kremlin's Cathedral Square.

Kremlin by night

Changing of the Guard in Cathedral Square (October 2014)

Visitor entrance

Site plan of the Kremlin buildings

Bird's eye view of the Kremlin

The Kremlin and Kitai-Gorod on the Moscow city map, here before the enlargement of the city area that took place on July 1, 2012.

History

Origin

The emergence of the Kremlin proper is closely connected with the foundation and further construction of the city of Moscow, which probably took place in the 11th or 12th century. Nevertheless, several excavations proved the existence of even much older human settlements on Borovitsky Hill. For example, traces of the Finno-Ugric people of the Merja from the Iron Age were found on parts of the present-day Kremlin site. The settlement of the banks of the Moskva River with Slavic peoples, who can be called the ancestors of today's Russians, on the other hand, began only at the end of the 1st millennium. At that time, numerous settlers from more southern areas of Kievan Rus opened up the very wooded areas of the East European Plain around the Volga and rivers from its catchment area, which had been considered unexplored until then. Their first settlements in the present-day Moscow city area can be traced to this day, above all on the basis of numerous burial mounds (so-called kurgans). Also directly on Borovitsky Hill, objects and remains of fortifications - including traces of an artificial moat up to nine metres deep and 3.8 metres wide - from the time before the Christianisation of Rus (end of the 10th century) have repeatedly been found during excavations.

When, around the 10th century, the first cities and smaller states (principalities) gradually began to form across the European part of present-day Russia, a fortified settlement may also have been built on the banks of the Moskva between the mouths of the Neglinnaya and Yausa rivers, which can be regarded as the first Russian precursor of the Kremlin. The Kremlin hill was very suitable for this purpose: this site on a natural elevation, which was washed by rivers on two sides and was originally also noticeably higher and steeper than today, had a strategically and defensively extremely favorable location. However, the exact date of the fortification's construction cannot be determined today. Officially, the year 1147 is considered to be the year of Moscow's foundation, but Moscow was mentioned in preserved written documents of that year as a settlement that had already existed for a longer period of time.

The origin of both the Kremlin and the actual city of Moscow can be clearly proven only from documents of the later 12th century. One of them dates back to 1147 and is at the same time considered to be the founding document of the city: it speaks of a pompous celebration that the Susdal Grand Duke Yuri Dolgoruky (literally "the long-handed") had organized in Moscow, which he supposedly founded, on the occasion of a military victory over parts of the then Republic of Novgorod. Therefore, the date of origin of the Kremlin is generally assumed to be 1156, when, according to a document from the principality of Tver, Yuri Dolgoruki had his newly founded city expanded as a castle in the fight against hostile principalities.

Early history

Since nothing remains of the original structures of the Kremlin today, conclusions about the possible appearance of the castle in the 12th century can only be drawn from archaeological finds. Apparently, the enclosure, like other defensive structures, was built of wood, since stone fortresses in Russian lands began to be built only a few centuries later. The total length of the enclosure was probably only about 500 meters; thus, the extent of the castle area was much smaller than today's and was limited to a small triangle in the area of the Neglinnaya estuary. Exactly there, in the southwestern part of the present Kremlin, remains of wooden piles from the 12th-century Kremlin wall were discovered in the mid-19th century during the construction of the armory building.

The name Kremlin did not appear in documents at that time, instead the fortified place on the Moskva River was simply called the city (Russian: город). The term Kremlin probably began to gain acceptance only from the 14th century. Its origin is most often assumed to be in Russian, or in Ur-Slavic; thus, fortified cores of larger Old Russian cities were sometimes called krom, krem, or kremnik (for example, the ancient core of Pskov was also called krom). However, there are also hypotheses that assume a foreign-language origin of the term: One of them, for example, says that kremlin was derived from the ancient Greek word krimnos for "steep [river] bank", which allegedly Byzantine guests had brought to Muscovy.

Due to frequent fires and raids, the wooden fortifications did not last and had to be rebuilt again and again. It is known, for example, that the Kremlin was burnt down by the Ryazan prince Gleb Rostislavich in 1179, only about 20 years after its presumed construction. Moscow was also attacked several times in the 13th century, by the Tatar Khan Batu in 1238 and again by Tatars under Tohtu in 1293. Both times the castle was devastated and its buildings destroyed or severely damaged.

The first radical renovation of the Kremlin began in 1339 under Grand Prince Ivan I "Kalita". The outdated castle, which had been damaged many times in previous attacks and fires (1331 and 1337), was demolished in order to build a new Kremlin in its place. Its walls, now about 1670 metres long, were built of solid oak and additionally covered with clay on the outside for better protection against fire. The complex was completed at the beginning of 1340 after a construction period of only a few months. Ivan also had a wooden grand prince's palace built in the Kremlin. Just over a decade earlier, in 1327, a stone church building was erected in the Kremlin for the first time, the Cathedral of the Assumption, the first predecessor of today's Kremlin Cathedral of the same name. Incidentally, at the same time Moscow Metropolitan Peter was the first Russian church leader to have a residence built in the Kremlin, marking the beginning of the Kremlin as the centre of power of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The wooden Kremlin of Ivan Kalita's reign was the first forerunner of today's Kremlin, the outline and structure of which are known to this day. Its territory was much larger than in the 12th century and covered about two thirds of the present territory of the Kremlin. Even then, Moscow proper was no longer limited to the Kremlin: more and more small merchants' and craftsmen's settlements sprang up around it, which a few decades later were protected from possible attacks by an additional fortification wall. Crafts as well as supra-regional trade flourished there, which was greatly favoured by the location on the navigable Moskva River. The most famous of the settlements on the left bank of the Moskva River in front of the Kremlin walls was the suburb of Kitai-Gorod immediately east of the Kremlin. Its central marketplace - later known as Red Square - still adjoins the Kremlin to the east and is extremely closely connected with it in its historical development.

First stone Kremlin

After the death of Ivan Kalita in 1340, his wooden Kremlin was to stand for another 25 years until a particularly devastating conflagration occurred in 1365, during which large parts of the oak walls also collapsed. As Moscow was still at war with several neighbouring principalities at that time, it was necessary to rebuild the castle quickly. This was initiated by the then Moscow ruler, Grand Duke Dmitri Donskoi. The construction began in the spring of 1367. To protect against the frequent fires, it was decided for the first time to have the new Kremlin built of stone instead of wood. For this purpose, large quantities of white limestone were prepared, which was mined in the Moscow area in numerous natural quarries.

The walls, which were still completed in 1367, were somewhat similar to today's Kremlin walls in terms of their construction - for the first time they were equipped with defence towers at strategically particularly important points. They were partly built on the foundations of the wooden predecessor Kremlin and, due to their white structure, gave Moscow the nickname Belokammennaya, literally "city of white stone" or "white city", which is still sometimes used today. With the exception of the northernmost tip, the fortified city centre of Moscow built under Dmitri Donskoi corresponded in size to the present-day Kremlin; the total length of the walls was just under 2000 metres.

The new, white-stone Kremlin lasted for over a century, with a few alterations and additions, and thus proved to be far more durable than any of its wooden predecessors. The inhabitants and defenders of the castle managed to successfully repel several enemy attacks in the late 14th and 15th centuries. Thus in 1368 and 1370, only a short time after the completion of the citadel, the Lithuanian prince Algirdas failed twice because of the strength of the Kremlin and the resistance of the Muscovites. Less successful, however, was Moscow's defense against the Tatar Khan Toktamish in 1382: after a three-day, initially unsuccessful siege, the latter's troops managed to outwit the city defenders and penetrate the Kremlin. There were over 20,000 casualties among the occupants; the white-stone Kremlin suffered considerable damage in the process. In the 1390s it was largely restored; at the same time new stone church buildings were erected there, among them the Church of the Nativity of the Mother of God in 1393, a replica of which, built in 1514, is still preserved today as one of the house churches of the Terem Palace.

The Kremlin takes its present form

A considerable part of the present structure of the Moscow Kremlin dates from the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries, when the fortifications were completely rebuilt and several new buildings were added inside the Kremlin, some of which still exist today. It was the reign of the Grand Prince Ivan III, who no longer considered the old castle, which had become dilapidated in many places, to be adequate for its role. The reason for this was, on the one hand, the considerable revival of the Moscow state, which now united all the former Russian principalities and was able to finally free itself from the centuries-long Mongol-Tatar invasion by 1480. On the other hand, Ivan's marriage to the Byzantine emperor's niece Sofia Palaiologa in 1472 also played a role: on the basis of this marriage, Ivan III saw himself as the rightful heir to the rulers of the defunct Byzantine Empire, which is why his Moscow residence was now to be elaborately expanded as an important centre of Orthodox Christianity (the so-called "Third Rome"). This prompted Ivan to invite several master builders from Italy to Moscow for the construction of the new fortress, the country in which his wife Sofia had also grown up and whose architects already enjoyed a high reputation in Russia at the time.

The reconstruction and expansion of the Kremlin, initiated under Ivan III and probably the most comprehensive to date, lasted practically his entire reign, i.e. for more than 40 years from 1462 to 1505. Among the first buildings erected in the process was today's Cathedral of the Assumption, which was completed in 1479. It was built on the site of the cathedral of the same name, which had collapsed a few years earlier, replacing its predecessor built in 1337. For its new construction Ivan III for the first time engaged an Italian architect, Aristotele Fioravanti from Bologna. He and several other masters invited from Italy - including Pietro Antonio Solari, Marco Ruffo and Aloisio Lamberti da Montagnana - created many of the Kremlin's buildings during Ivan's reign, including above all the entire fortifications, including the wall and defence towers.

This wall, built between 1485 and 1499, is essentially the Kremlin wall that has survived to the present day, and the towers built at the same time are also the same, although most of them have been heavily modified over the centuries. The Italian builders, who were guided in the construction of the Moscow city fortifications not least by comparable buildings in their homeland - including the Milanese Castello Sforzesco - used brick for the first time in the history of Moscow city construction, which gives the Kremlin its typical dark red colour to this day - instead of the former white. The towers were built within firing distance of each other; however, they received their now characteristic tent roofs and spires only at the end of the 17th century. To protect the fortress from fires and improve its defensive capabilities, a decree issued by Ivan III in 1493 forbade the construction of wooden houses within a radius of a good 200 metres outside the wall; existing buildings were also soon relocated.

Within the Kremlin walls, among the buildings that were erected at the end of the 15th century, apart from the Cathedral of the Assumption, the most noteworthy is the splendidly furnished Facet Palace, which today belongs to the ensemble of the Great Kremlin Palace, which was only completed in the 19th century. Built in 1491 by Marco Ruffo and Pietro Antonio Solari as an addition to a grand ducal palace that already existed at that time and is no longer preserved today, the Facet Palace served the grand duke from then on as a representative place for ceremonial receptions and acts of state. At about the same time the present ensemble of the Kremlin's Cathedral Square was largely completed: The Cathedral of the Dormition and the Facetted Palace were joined by the Church of the Laying Down of the Robe of the Virgin Mary (completed in 1486), the Cathedral of the Annunciation (1489), the Archangel Michael Cathedral (1508), and finally the Ivan the Great Bell Tower (1508).

The expansion of the Kremlin initiated by Ivan III continued - with interruptions due to still frequent conflagrations - even after his death until about 1516, when an artificial moat was laid along the eastern section of the Kremlin wall adjacent to the Red Square, from the Neglinnaya to the Moskva. The moat was built by the Italian Aloisio Lamberti da Montagnana - in Russia at that time it was simply called Alewis (the New), which is why it was called Alewis' Moat. The moat was about 32 meters wide and 12 meters deep and was fed by artificially dammed water from the Neglinnaya. Until the beginning of the 19th century, when the moat was filled in, it provided the Kremlin with additional protection from the eastern side, where there were no natural waters. With the completion of the great reconstruction by Ivan III, the Moscow Kremlin was thus surrounded by water on all three sides, so that it was possible to enter the fortress only through special draw-wire bridges, which were raised in case of attack. Moreover, the extent of the Kremlin's territory at that time reached its present dimensions.

In the further course of the 16th century - so under Ivan IV "the Terrible", when the Moscow principality expanded territorially further and was finally declared a unified Tsardom of Russia in 1547, thus advancing the Kremlin to the residence of Russian tsars - there was comparatively little building activity on the Kremlin grounds. There were individual smaller church and residential buildings, which are no longer preserved today, as well as the Golden Tsarina Chamber, which was later almost completely closed, and the extension to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, known today as the Uspensky Bell Tower. At that time, the Moscow Kremlin, which was considered closed at the time, served as a model for a number of other Russian cities, which, due to their location near the border, knew how to protect themselves by building similarly constructed citadels. Kremlins based on the Moscow model were built in Rostov-on-Lake, Tula, Serpukhov and other Russian cities. Some of these former fortresses have been preserved, at least in parts, to this day. The fortification wall with towers of the Holy Trinity Monastery of Sergiyev Possad, the most important Russian Orthodox monastery at that time, built in the 1550s, was also strongly modelled on the wall of the Moscow Kremlin.

The Kremlin in the 17th century

As late as the beginning of the 17th century, Tsar Boris Godunov planned new ambitious building projects in the Kremlin during his short reign (1598-1605), but only the addition of the current spire to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower and the construction of a new Tsar's palace, which was demolished in the 1770s, came to fruition. A few years later, all building activity in Moscow and other Russian cities came to a temporary halt when large parts of the Russian Tsardom were dominated by Polish-Lithuanian invaders. During this period, known as Smuta, from 1598 to 1613, the Kremlin was also temporarily affected when its buildings were damaged in battles and a large number of treasures and works of art were looted from the Kremlin churches. Any restoration work on existing buildings, as well as construction work on new ones, could be started only during the reign of the first tsar of the Romanov dynasty, Michael I. Thus, in 1624 he had the Ivan the Great bell tower extended by an additional side tower with a tent roof, the so-called Philaret annex. In 1621 the main watchtower of the Kremlin - the Saviour's Tower, where the main entrance from the Red Square was located - was the first Kremlin tower to be rebuilt and raised. Later, towards the end of the century, most of the other Kremlin towers were rebuilt in a similar way, receiving their decorative tent roofs, which are still characteristic today.

Another striking new building in the Kremlin of the 17th century was constructed in 1635-1636: this is the Terem Palace, now part of the Great Kremlin Palace, which served as the residential residence of Russian tsars and their family members until the end of the century. Finally, it is worth mentioning the buildings of the Twelve Apostles Church and the residential and working residence of the Moscow Patriarch, erected in a contiguous complex of buildings. They were completed in 1656 and since then have been able to express in a special way the importance of the Kremlin not only as the residence of secular rulers, but also as the spiritual centre of the Russian Orthodox Church.

As the oldest and most centrally located part of the tsarist capital Moscow, which in the meantime has grown far beyond the old fortress walls in all directions, the Kremlin has certainly not only served the tsarist family and the head of the church as a place of residence. As early as the 14th century, one of the most famous Russian Orthodox monasteries of the time was located there - the Chudov Monastery, which fell victim to the Communists' demolition campaign at the beginning of the 20th century. Therefore, in the 17th century the Kremlin had long been considered a highly venerated place of pilgrimage, whose main entrance gate in the Saviour's Tower could only be passed on foot and with an uncovered head. But it was also the center of public life for the Muscovites; state and folk festivals were held here, and it was here that the tsars appeared before the people on special occasions or had their decrees and other important announcements proclaimed to the people. In the 17th century the privilege of living in the Kremlin was reserved, apart from the tsar and the clergy, only for particularly rich and venerable nobles (boyars) and their families. The only surviving example of a boyar residence of that time in the Kremlin is the so-called Palace of Pleasure from 1651, which originally served as the residence of the Miloslavski family and was converted a few years later as one of the first Russian venues for theatrical performances for the "amusement" of the tsar's family.

The Kremlin from the 18th to the 19th century

| Chronological development of the | ||||

| Construction time | Building | Conversion/expansion | ||

| 1475–1479 | Cathedral of the Assumption | |||

| 1484–1486 | Assumption Church | |||

| 1484–1489 | Cathedral of the Annunciation | 1564 | ||

| 1485–1499 | Fortification wall and towers | 17th-19th c. | ||

| 1487–1492 | Facet Palace | |||

| 1505–1508 | Archangel Michael Cathedral | 18th century | ||

| 1505–1508 | Ivan the Great Bell Tower | 1543, 1600, 1823 | ||

| End of 16th century | Golden Tsarina Chamber | |||

| 1635–1636 | Terem Palace | |||

| 1651–1652 | Pleasure Palace | et al. 1875 | ||

| 1653–1656 | Patriarchal Palace | |||

| 1702–1736 | Arsenal | 1796, 1828 | ||

| 1776–1787 | Senate Palace | |||

| 1838–1849 | Great Kremlin Palace, main building | |||

| 1844–1851 | Armory | |||

| 1930–1934 | Administration building | |||

| 1960–1961 | State Kremlin Palace | |||

The beginning of the 18th century marked two historical events for the Kremlin. On the one hand, the then Tsar Peter I "the Great", who a few years later declared himself the first emperor of the Russian Empire, which in the meantime had expanded far into the Asian hinterland, had the new capital of this empire moved from Moscow to the newly founded Saint Petersburg, with which the Kremlin lost its status as the Tsar's residence. Secondly, in 1701 the fortress was hit by one of the most momentous major fires in its history, destroying most of the wooden buildings that remained there. Regardless of the damage, this fire gave a new impetus to building activity in the Kremlin: a large plot of land was uncovered on the western section of the Kremlin wall, on which Peter soon ordered the construction of an armoury (or, as he himself called it, an "armoury"). Thus began the creation of the present arsenal building, which is one of the most striking Kremlin structures of the 18th century. However, construction progressed slowly due to the financial difficulties caused by the Great Northern War, so that the arsenal was not completed until 1736.

In 1753, under Empress Elisabeth, a new Moscow residence of the Russian Tsar was built on the Kremlin grounds, near the southern section of the wall, which is the immediate predecessor of today's Great Kremlin Palace. In 1787, another architecturally charming building was erected in the Kremlin near the Arsenal, the Senate Palace, which is now the core of the Russian President's official residence. The Senate Palace was also the only major building project in the Moscow Kremlin that was realized under Catherine II "the Great". In addition, Catherine planned a radical reconstruction of the Kremlin, including the construction of a new imperial residence of huge dimensions, to which a large number of old buildings were to give way. Although the plans had to be abandoned in the 1770s, partly due to a lack of money and fierce criticism, parts of the southern Kremlin wall had already been demolished in preparation for the construction. While these sections of the wall were restored a few years later, several historic buildings in the southern part of the Kremlin that had also been demolished earlier - including the former palace of Tsar Boris Godunov - finally disappeared from the cityscape of the Moscow Citadel.

In 1812 the Kremlin ensemble again suffered considerable destruction when the entire city of Moscow was temporarily under French occupation during Napoleon Bonaparte's Russian campaign. During the stay of Napoleon's troops on the Kremlin premises a large number of church treasures were looted or damaged, as the soldiers used the Kremlin cathedrals as barracks or horse stables. The Kremlin was hit even harder when the French army was forced to retreat: in revenge for his defeat, Napoleon wanted to have the entire Kremlin blown up, along with its fortifications and other architectural monuments. The area was mined, but due to heavy rain and the fierce resistance of the local residents, among other things, explosions only occurred in places. Nevertheless, several Kremlin towers were badly damaged, with the tent roof of some of them toppling over; there was also considerable damage to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, the Facet Palace and the Arsenal building, which had only recently been restored after a fire. Reconstruction work on the Kremlin continued into the 1830s. A large part of it was directed by the architect Joseph Bové. In the process, he also completely redesigned the immediate surroundings of the Kremlin: the bed of the Neglinnaya River was moved to an underground canal, where it remains today, and in its place, along the western section of the Kremlin wall, the Alexander Garden was laid out, an elongated public park with flowerbeds and a decorative grotto. Red Square was also redesigned, with the old Alevis Ditch along the Kremlin Wall filled in in favor of a new promenade.

At the end of the reconstruction work in the Kremlin, work finally began on building a new Moscow residence for Russian tsars, precisely where grand dukes' and tsars' apartments had stood since the 14th century, most recently the palace from 1753, which had also been badly damaged in 1812. Tsar Nicholas I commissioned the famous city architect Konstantin Thon with its realization, who built a new classicistic imperial residence between 1844 and 1851, which together with the already existing buildings of the Facet Palace and the Terem Palace forms today's ensemble of the Great Kremlin Palace. Almost at the same time, to the left of the new tsar's residence, Thon built the new building of the armoury, which was connected to the palace by a roofed gallery.

Constantine Thon's projects represented the last major construction activities in the Kremlin in the 19th century and gave the southern part of the Kremlin, facing the Moskva River, the shape that has been preserved to this day, except for a few fine details. At the beginning of the 20th century the Kremlin with its two monasteries - the Chudov Monastery and the Assumption Monastery - was still primarily one of the most important Orthodox pilgrimage sites. Despite the transfer of the tsarist capital to St Petersburg, the Kremlin remained one of the centres of state power in the 18th and 19th centuries, as all important acts of state - including the solemn tsarist coronation ceremonies - still took place in the Moscow Kremlin. In addition, the Kremlin was still a comprehensive museum complex during the time of the tsars, and a visit to it was considered obligatory for every visitor to Moscow and was therefore open to the public almost without restriction. However, the latter changed after 1917.

The Kremlin in Soviet times

For Moscow, the October Revolution of 1917 was associated not only with decisive social upheaval and the end of the Russian Tsarist Empire, but also with several days of bitter fighting, from which the Kremlin ensemble in particular suffered. After anti-Bolshevik forces succeeded in temporarily regaining control of the Kremlin on October 28 (on November 10, new style), Red Guard units laid siege to the fortress and shelled it permanently with artillery. By the time the Kremlin was finally taken on November 2, a number of buildings had suffered visible damage: several Kremlin towers - including the Saviour's Tower and its clock tower - were badly damaged in places, and there was also considerable destruction to the Chudov Monastery complex and the Cathedral of the Assumption. After the end of the fighting, the so-called Revolutionary Necropolis was laid out in front of the eastern Kremlin wall on Red Square for the approximately 250 Red Guards who had fallen at that time, where other prominent revolutionaries and statesmen of the Soviet Union were later buried.

The years that followed marked further drastic changes in the history of the Moscow Kremlin. The new Soviet Russian government, including revolutionary leader Lenin, moved from Saint Petersburg (at that time called Petrograd) to Moscow on March 12, 1918, in a secret night-and-fog action, as the new rulers hoped for better protection against possible uprisings, coups or foreign interventions behind the walls of the Kremlin. Thus, after two centuries, Moscow regained the capital status it still holds today. Several Kremlin buildings - including the former commandant's residence at the Palace of Pleasure, the barracks in the Arsenal and also parts of the Great Kremlin Palace - were used as residences for statesmen and their relatives and servants. Lenin also had workrooms and a small apartment set up in the Kremlin Senate Palace. This apartment, along with its original furnishings, was retained after Lenin's death and remained open as a museum until the 1990s.

For the Kremlin, which was now once again the seat of state power, the arrival of the government brought not only a rapid reconstruction of the buildings damaged during the fighting. As a highly secured residence, the Kremlin closed its gates to the general public in 1927 and could not be entered without a pass ever since. All of the Kremlin's resident clergy were also expelled from there during the 1920s. The two monasteries on the Kremlin grounds - the Chudov Monastery and the Ascension Monastery - which had been badly damaged during the fighting in 1917, were initially closed as part of the Bolsheviks' anti-religious campaign, to which a large number of other sacred buildings throughout Russia also fell victim, and were finally completely demolished in 1929. On the vacated site the new neoclassical building of the Military School for Commanders of the Red Army was built by 1934. Today it is known as the Kremlin Administration Building (or Building 14) and is part of the presidential residence within the Kremlin.

Under Lenin's successor Josef Stalin, who also had an apartment set up in the Senate Palace of the Kremlin, further demolitions and architecturally not always successful reconstructions of old buildings were carried out. In 1933 the Great Kremlin Palace was converted into a meeting place, for which purpose one of the oldest surviving Kremlin buildings - the neighbouring Church of the Saviour in the Forest from the 1330s - was demolished and two historic parade halls inside the palace were combined into one large meeting hall. Finally, from 1935 to 1937, the gilded double-headed eagles from the tsarist era were removed from the tops of the Kremlin's four passage towers and replaced with Soviet stars made of red ruby glass to symbolize the new ideology and the victory of the socialist revolution. In 1937, such a star was also placed at the top of the water-draught tower at the southwest corner of the Kremlin wall, which was visible from afar.

During the Battle of Moscow in the Second World War and the frequent air raids on Moscow at the time, the damage to the Kremlin remained comparatively minor, as the fortress was well secured by building camouflage and additional anti-aircraft installations. The movable treasures, including exhibits from the armoury, were evacuated to the Soviet hinterland as a precautionary measure before the start of hostilities. Nevertheless, there were isolated cases of damage to property and personal injury: on 12 August 1941, for example, a bomb hit the Arsenal, killing 20 soldiers, and the bombing on 29 October of the same year left 41 dead and over 100 injured in the Kremlin.

After Stalin's death, his comparatively liberal successor Nikita Khrushchev relaxed the rules on visiting the Kremlin: from 1955 onwards, the ensemble within the Kremlin walls could once again be entered and visited by the public free of charge. Also, by 1961, the last remaining official residences on Kremlin territory were dissolved. Large parts of the ensemble were prepared as a museum, on the basis of which the Kremlin received the highest possible Russian monument protection status of a state museum reserve three decades later.

The Congress Palace of the Moscow Kremlin, now known as the State Kremlin Palace, was also built during Khrushchev's reign and is the youngest building on the Kremlin grounds to date. It replaced the Great Kremlin Palace as the central meeting place of the CPSU and is now used primarily for cultural events. Since the completion of the Congress Palace in 1961, nothing new has been built on the Kremlin grounds, only restoration work on existing buildings has been carried out, for example in the 1970s in the run-up to the XXII Olympic Games held in Moscow.

From the end of the 20th century to the present

With the opening of the Soviet Union during the perestroika period of the late 1980s, the Kremlin's significance as an important sight in the country increased increasingly for foreign visitors as well. Despite the damage to the substance of the historic ensemble caused by the construction and demolition campaigns of the 20th century, most of which was irreparable, the Kremlin - together with the neighbouring Red Square - therefore became the first structure on Russian territory to be inscribed by UNESCO on the World Heritage List. The inscription was made in December 1990 on the basis of a recommendation made the previous year by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). As a national cultural heritage site, the Kremlin, together with other objects recognized as such, is under special protection under the Law on Objects of Cultural Heritage of the Peoples of Russia adopted in 2002.

In the 1990s and 2000s, further restoration work was carried out in the Kremlin with the aim of preserving the historical substance as an open-air museum. Some of the interventions in the ensemble dating back to the Soviet era were reversed; for example, the two parade halls in the Great Kremlin Palace, which had been taken out of service in the 1930s, were faithfully restored. Even though the Kremlin, as the presidential residence, is currently only partially open to the public, as the oldest part of Moscow it remains its undisputed most important tourist attraction with around two million visitors a year.

The Kremlin also currently plays a certain role again in Moscow's spiritual life, although it is no longer considered a place of pilgrimage for Orthodox believers, as it was before the October Revolution. The Kremlin's four main surviving church buildings - the Cathedral of the Assumption, the Archangel Michael Cathedral, the Cathedral of the Annunciation and the Church of the Laying Down of the Vestments - were returned to the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the early 1990s and now serve not only as museums, They now serve not only as museums, but also as places of worship, where solemn liturgies take place on certain church feast days, as well as church services with the participation of the Moscow Patriarch and often also high members of the government.

The Secret Corridor Garden in the southern part of the Kremlin has recently been restored as a landscape garden. The ornately decorated fountain in the garden was inaugurated in May 2008

Panorama of the Kremlin (1968)

The Church of the Redeemer in the Forest, which was last enclosed by the Great Kremlin Palace (here photo from 1882), was demolished in 1933 during its partial reconstruction.

The Kremlin in Moscow (1842) by Noël Marie Paymal Lerebours. One of the first photographs of the Kremlin.

The Kremlin in the 1840s: On the left is the old building of the armoury, in the background the Trinity Tower, on the right the Arsenal

The Kremlin around 1796 with a view of Moscow: copperplate engraving by Matthias Gottfried Eichler after a drawing by Gérard de la Barthe

Ivan Square of the Kremlin in the 17th century with the Ivan the Great Bell Tower in the background. A watercolor (1903) by Apollinari Vasnezov

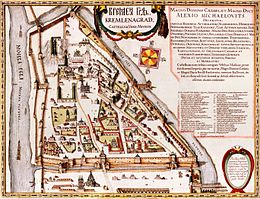

The so-called Kremlenagrad, created by an unknown author around 1600, is the first known map of the Moscow Kremlin. With its detailed and authentic depiction of the development of the Kremlin and Red Square at that time, it resembles a bird's-eye view of the terrain.

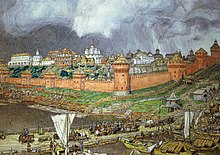

The Kremlin under Ivan III A watercolour (1921) by Apollinari Vasnezov

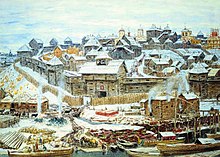

First Stone Kremlin. A watercolor (1922) by Apollinari Vasnezov

The wooden Moscow Kremlin under Ivan Kalita. A watercolor (1921) by Apollinari Vasnezov

Search within the encyclopedia