Mongolia

![]()

This article describes the Mongolian state since 1992. For other terms, see Mongolia (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/TRANSCRIPTION

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/NAME-German

Mongolia ([mɔŋɡoˈla͜i], officially in Mongolian Монгол Улс Mongol Uls, ᠮᠤᠩᠭᠤᠯ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ mongɣol ulus, literally Mongolian state) is a landlocked country in the eastern part of Central Asia, located between Russia to the north and the People's Republic of China to the south. Its area covers most of the Mongolian Plateau. Territorially almost four and a half times the size of Germany, the country is the most sparsely populated state in the world with about 3 million inhabitants. The largest city is the capital Ulaanbaatar, where more than 40 percent of the country's population lives.

Due to the soil conditions and the climate, little agriculture can be practiced in Mongolia. The landscape is dominated by grassy steppes, with mountains in the north and west, and the Gobi Desert in the south. The most important economic sectors are nomadic livestock farming and mining. The country is one of the ten most resource-rich countries in the world. The majority of the inhabitants are Buddhists. In total, about 62 percent of the population belong to a religious community, of which 91.6 percent profess Lamaism.

Excavations in the Gobi prove that already 500,000 years ago Homo erectus lived in the area of today's Mongolia. Even before the beginning of the Christian era, equestrian nomads, such as the Xiongnu or Xianbei, united to form large tribes. In 1206 Genghis Khan founded the Mongol Empire, which stretched across Asia to Europe and represented the largest territorially contiguous empire in human history. His grandson Kublai Khan conquered China and founded the Yuan Dynasty. After the collapse of this empire, Buddhism increasingly developed as a form of government. During the Qing Dynasty, Outer Mongolia was created as a province in 1644 on the territory of the present Mongolian state. From 1912, the region gained extensive autonomy rights. In 1921 the Soviet Union established a puppet government, which proclaimed the Mongolian People's Republic in 1924. During its existence, it was completely dependent on the Soviet Union politically, militarily and economically.

In the wake of the 1989 revolutions, the country made a peaceful transition to a democratic parliamentary system of government. On 12 February 1992, the parliament sealed the end of the communist system by adopting a new constitution. At the same time, the constituent power of the new state of Mongolia renounced the name People's Republic.

Geography

Mongolia is a country in Central Asia. Its territory extends between 41° 35′ and 52° 06′ north latitude and 87° 47′ and 119° 57′ east longitude. Among all the states of the world, it occupies the 18th place in terms of its area. Despite this, Mongolia has only two neighbors: with Russia to the north, the country shares a 3485 km border, and with the People's Republic of China to the south, a 4677 km border; in addition, Kazakhstan begins only 38 km west of the westernmost point of Mongolia. Its east-west extent is 2392 km and its north-south extent is 1259 km. It is 40% covered by semi-desert, 35% by tree steppe, and 20% by grass steppe; forest and sandy desert make up the rest.

The largest city in Mongolia is the capital Ulaanbaatar (Ulan Bator) with about 1.3 million inhabitants, almost half the population of the whole country. The emergence of Maidar City will not remedy the centralization of the population around Ulaanbaatar, as the two cities will be only about 30 km apart. Major cities include Erdenet with a population of 79,649, Darchan with a population of 72,386, and Choibalsan with a population of 44,367; for more cities, see the list of cities in Mongolia.

Surface shape

About one third of the national territory is occupied by high mountains, especially in the north, west and southeast. The south and east are dominated by dry plateaus. The average altitude of the country is about 1580 meters above sea level.

Western Mongolia is the name given to the region between the Changai Mountains and the Altai. Here, on the border with the Chinese Xinjiang, two peaks of the Altai reach almost 4400 meters, including the Chüiten peak, which at 4374 m is the highest elevation in Mongolia. From there, the 3000- to 4000-meter-high Mongolian Altai and Gobi-Altai mountain ranges extend 2000 km to the east-southeast, along the border with China, to the Mongolian Plateau; other mountains in western Mongolia include the Tannu-ola Mountains and the Sajan Mountains. Mongolia has hundreds of glaciers, although all are very small by international standards.

In the centre of the country are the Changai Mountains with numerous three-thousand-metre peaks, whose northern flank already drains to Lake Baikal in Siberia, and to the east the region around the capital Ulaanbaatar (1350 m). To the east of this is the Chentii Mountains. South of this mountain range the country is hilly until it changes into the Gobi. In the east of Mongolia, the lowest point of Mongolia is at Lake Choch Nuur, at 532 m.

Waters

Mongolia has about 1200 rivers with a total length of almost 70,000 km. The country is drained in three directions: towards the Pacific Ocean, towards the Arctic Ocean and towards the drainless Central Asian Plain. As a landlocked country, Mongolia itself has no access to seas or oceans.

The north is crossed by the water-rich rivers Selenga and its large tributaries Ider, Orkhon and Tuul. These rise in the Changai Mountains and flow into Lake Baikal. Also flowing to the north and east are the Onon and Cherlen, which rise in the Chentii Mountains and drain to the Pacific via the Amur, also the Ulds and Chalchyn. The largest rivers of the west are the Chowd and the Dzavkhan, both of which flow toward drainless Central Asia. All of Mongolia's rivers freeze over in winter. The ice cover can remain for up to half a year and reach a thickness of more than one meter. The frozen rivers are often used as roads by vehicles in winter, polluting them with oil.

Mongolia's nearly 4000 lakes include the 3350 km² saltwater Lake Uws Nuur and the 2760 km² Chöwsgöl Nuur. The latter is one of the most important freshwater lakes in the world. 95% of the other lakes are less than 5 km² in size; 80% are freshwater lakes. As they are often fed by glaciers and are far from any industrial centres, they are almost unpolluted and have very clear water. They are important resting places for migratory birds.

Mongolia's water bodies are affected by significant desertification, 852 of the rivers and streams and more than 1000 of the lakes have dried up or disappeared (2007 data).

Climate

Mongolia's location in the Central Asian highlands gives it one of the most extreme climates among the world's continental and arid climates. Due to the dry, pronounced continental climate, temperatures fluctuate greatly throughout the year: in winter, average daily temperatures are -25 °C, in summer +20 °C, which means that the fluctuations are two to three times greater than in Western Europe. The average annual precipitation reaches 200 to 220 millimeters, decreasing from over 400 mm in the north of the country to less than 100 mm in the south of the Gobi Desert. In the annual cycle, 80 to 90% of precipitation falls from May to September. Temperature differences between night and day are also unusually high, reaching up to 32 °C. The absolute temperature amplitude between summer and winter reaches up to 100 K.

Effects of climate change

Mongolia is significantly affected by global warming. Between 1940 and 2001, the annual mean air temperature rose by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. Winter temperature has even increased by more than 3.6 degrees during this period. Mongolia's ancient ice is melting rapidly due to the changing climate and warm summer temperatures. As the inflow from the ice fields runs dry more frequently in the summer, drinking water supplies are becoming increasingly limited. This will put both cultural heritage and traditional reindeer husbandry at extreme risk in the coming years. As a result, the climate crisis is endangering indigenous low-latitude reindeer herders living in the mountainous tundra zones of northern Mongolia.

Vegetation

While the northern part of Mongolia is still part of the boreal coniferous forest zone with sufficient precipitation supply, precipitation decreases continuously in the southern direction. The natural conditions such as the precipitation gradient in north-south direction and the windward-leeward effects of the mountain ranges crossing the country lead to a distinct vegetation zonation, which Hilbig 1995 distinguished according to the precipitation conditions from north to south as follows (their distribution in the corresponding geographical areas and floral regions according to Grubov 1982 is mentioned in brackets):

- Mountain taiga (Chubsugul, Chentei, northern edge Changai)

- (Mountain) Forest Steppe (Changai, Chubsugul, Chentei, Mongolian-Daurian Floral Region, Mongolian Altai, Hinggan)

- (Dry) steppe (southern Changai, central Khalcha, eastern Mongolia, rim of the Great Lakes basin)

- Grass steppe

- Mountain Steppe

- Meadow Steppe

- Sand steppe

- Alpine vegetation (Chubsugul, Chentei, Changai, Mongolian Altai)

- Semi-desert (desert steppe) (southern half of Mongolia, Great Lakes basin, Gobi-Altai, Jungarian Gobi)

- Desert (Jungarian Gobi, Transaltai Gobi, Alashan Gobi and East Gobi)

Extrazonal vegetation:

- Alpine vegetation (formed in the Chubsugul area, in the central Changai, in the Mongolian Altai, partly in the Chentei)

Fauna

The fauna of Mongolia has adapted to the conditions of the steppe. People keep sheep, goats, cattle, camels and horses. Wild mammals of the steppe include saiga, jumping mouse species, marmot, wolf, yak, a wild cat species and the steppe tilis. At the lakes a crane species occurs, as further bird species of Mongolia are buzzard species, steppe eagle, the lark and a wheatear species known. A special feature is the Przewalski's horse, which was already extinct and was successfully reintroduced into the wild. The forest and mountain areas of the country are inhabited by the argali, a wild goat species, a gazelle species, the stoat, the snow hare, snipe species and the Altai king chicken (Tetraogallus altaicus). A special feature here is the snow leopard, which is highly endangered due to hunting and the restriction of its habitat. The Gobi is home to the Asian donkey, the cashmere goat, numerous species of rodents and lizards and agamas. The Gobi is also home to the critically endangered gobi bear, a small form of brown bear that eats a mainly vegetarian diet. Carp fish, loach-like fish, pike, the burbot, the perch, the lenok, the taimen and various species of grayling are found in the waters of Mongolia. The Baikal sturgeon (Acipenser baerii baicalensis Nikolskii) migrates more than 300 km across the Orkhon River to spawn in the Selenga River and the upper reaches of the Orkhon River. Migratory birds that spend only the summer in Mongolia are the swan goose, mute swan and teal. There are also migratory birds that spend the winter in Mongolia, such as the snow bunting or the snowy owl.

Paleontology

Due to the region's formerly warm and humid climate, which later became dry and cool, numerous dinosaur remains have been preserved. Since the 1920s, numerous spectacular finds have been made in Mongolia. For example, the American scientist Roy Chapman Andrews discovered the first dinosaur eggs here. Fossils of Oviraptor, Protoceratops, Velociraptor, Therizinosaurus, Pachycephalosauria and Tarbosaurus have also been found.

Natural disasters

Mongolia is located in a seismically very active area; earthquakes are frequent. However, because of the low population density and because there are relatively few buildings that could collapse, the quakes usually cause only minor damage. The most violent earthquakes occurred in central Mongolia in 1905 and in southwestern Mongolia in 1931, 1957, and 1967. The 1905 quake had a magnitude of 8.2 to 8.7 on the Richter scale, the 1957 quake had a magnitude of 7.9 to 8.3, and the 1967 quake had a magnitude of 7.5. However, the numerous earth fissures left by the quakes often cause river courses on which the nomads and their herds depend to dry up or shift.

Dsud was originally used to describe very snowy winters in which the animals are no longer able to find fodder under the snow cover and therefore starve to death. In the meantime, however, the term is also used for other, especially wintry, meteorological conditions under which it becomes impossible for cattle to graze. Thus, in addition to the aforementioned White Dsud, in which the animals can no longer find food under the snow cover after heavy snowfall, a distinction is made between the so-called Black Dsud, in which the animals die of thirst due to insufficient snow (since wells and bodies of water freeze, snow is the only source of water in cold temperatures). Another form is Icy or Iron Dsud, in which freezing rain covers the land with ice, preventing animals from feeding on grass and herbs. Finally, a fourth form is Storm Dsud due to sandstorms. Dsuds are relatively common phenomena in Mongolia, and millions of animals can fall victim to them in a single winter, depriving the population of its food base.

Management structure

→ Main article: Aimags of Mongolia and Sum (Mongolia)

Mongolia is divided into 21 Aimags (provinces) and the capital Ulaanbaatar (Ulan Bator), which forms an independent administrative unit. The latter also applied to the city of Erdenet until 1994. In 1994, however, the city of Erdenet, together with some sums of the Bulgan Aimag, became the Orkhon Aimag. The same applies to the city of Darchan, for which the Darchan-Uul-Aimag was separated from the Selenge-Aimag as an enclave.

Each Aimag is divided into a number of Sum (comparable with counties/districts), these in turn into Bag (comparable with municipalities). There are over 300 sums, which are divided into more than 1500 bags. A bag often does not exist as a fixed settlement, as its members all move around as nomads.

Cities

See also: List of cities in Mongolia

In 2016, 72.8% of the population lived in cities or urban areas. The capital Ulaanbaatar is very dominant in this regard, as about 41% of Mongolia's population lives there. The 5 largest cities are (as of 2017):

- Ulaanbaatar: 1,311,251 inhabitants

- Erdenet: 98,050 inhabitants

- Darchan: 82,247 inhabitants

- Choibalsan: population 43,106

- Mörön: 38,582 inhabitants

Provinces of Mongolia

Yurt in the Gobi

Maiden cranes can be observed frequently, especially in northwestern Mongolia.

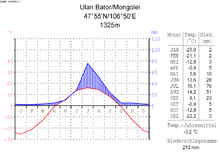

Climate diagram of Ulaanbaatar

Bactrian camels in the Gobi Gurwan Saichan National Park

Ider near Djargalant (Chöwsgöl-Aimag)

Population

| Ethnic groups of Mongolia (2000) | ||

| Ethnicity | Number | Share |

| Chalcha | 1.934,7 | 81,5 |

| Kazakhs | 103,0 | 4,3 |

| Dörwöd | 66,7 | 2,8 |

| Bajad | 50,8 | 2,1 |

| Buryat | 40,6 | 1,7 |

| Dariganga | 31,9 | 1,3 |

| Zakhchin | 29,8 | 1,3 |

| Urianchai | 25,2 | 1,1 |

| Other | 82,6 | 3,5 |

| Foreigners | 8,1 | 0,3 |

| Total | 2.373,5 | 100,0 |

Population groups and development

The vast majority of the population of Mongolia (about 85%) belongs to the Mongolian people. The subgroups of this people are essentially distinguished by their respective dialect. Minorities from various Turkic peoples, such as Kazakhs and Tuvinians (Urianchai), live mainly in the west of the country (Bajan-Ölgii-Aimag and Chowd-Aimag). Immigrant Russians and Han live mainly in the cities or as skilled workers in the mining industry. However, the proportion of Russians has declined sharply after democratisation.

Next to Western Sahara, Mongolia is the most sparsely populated state in the world. However, the population had more than doubled between 1960 and 1990. Within the framework of the Five-Year Plan (1948-1952) of the Socialist People's Republic, population growth had been targeted in order to make agricultural and industrialization goals attainable. As a result, incentives were created to have large numbers of children: Women with more than four children received awards, free recreational leave, higher child benefits, and early retirement.

Fertility dropped abruptly in the early 1990s due to the transition to a market economy and the new problems that emerged with it; in 1993 it was 2.6 births per woman and in 2015 (estimated) 2.2; a further drop was expected. The 2000 census still noted a population growth of 1.54%; an estimated 1.31% was given for 2015. 45% of the population is under 25 years of age, 27% under 15.

In 2017, 0.6% of the population was foreign-born. Most foreigners are from China, Russia and South Korea.

Health

Mongolia experiences periods of extreme cold, which has an impact on the life expectancy of the rural population. The average life expectancy is 69 years (2015 estimate), with men living to an average of 65 and women to 73. In 2006, government health spending was $124 (purchasing power parity) per capita.

Languages and scripts

→ Main articles: Mongolian languages and Mongolian scripts

The Chalcha-Mongolian language, as the most important representative of the Mongolian language family, is the mother tongue of about 85 percent of ethnic Mongols. The remainder is largely composed of Buryats in the north, Durbet in the northwest, Dariganga in the southeast, and Western Mongols (Oirats and the like) in the west. The remaining minorities in the west speak various Turkic languages (mainly Kazakh, but also Tuvan). During socialism, Russian was taught to students. Since 2005, English has been taught in schools as the official first foreign language instead. About 30,000 Mongolians speak German as a foreign language.

The adult literacy rate exceeds 98 percent, according to the UN. The Mongolian language is written in Mongolia today in a slightly expanded Cyrillic alphabet. The traditional Mongolian script, which originated in Uighur, is written vertically. After the end of communist rule, it was officially decided to reintroduce it, but in practice this has little chance of being realised, if only for economic reasons. In Inner Mongolia, however, the traditional script is still in use.

Religion

→ Main article: Religions in Mongolia

The original religion of the Central Asian steppe dwellers was shamanism. Elements of shamanism live on in Buddhism to this day (→ syncretism). Today, shamanistic traditions are playing an increasing role again. For example, oboo - cairns on hills or at crossroads where everyone who says a prayer adds a stone - are once again more common, and even official recognition has been given to the cult of the mountain deities of Mount Burchan Chaldun.

Buddhism was introduced to Mongolia several times: In the 1st century BC by the Xiongnu, in the 6th century by the Jujuan, in the 10th century by the Khitan. In the world empire of Genghis Khan, where all religions were encouraged, Buddhism was only one among several religions. In the 16th century, the Tibetan form of Buddhism (Vajrayana) established itself in Mongolia. Altan Khan, who had ambitions to unite the Mongolian tribes under his leadership, assisted the priests of the Gelugpa school in spreading their teachings and gaining supremacy in Tibet. In return, he had himself declared the reincarnation of Kublai Khan. In 1578, the title of Dalai Lama was conferred for the first time on Sonam Gyatso (his two predecessors were appointed posthumously); from that year onwards, Buddhism, starting from Hohhot, spread in several waves throughout Mongolia. In 1586, the Buddhist monastery of Erdene Dsuu, which housed over 60 Buddhist temples, was built from the stones of the former capital of Karakorum on a 16-hectare site.

Lamaism, especially its Tibetan lineage Gelugpa, slowly became a dominant force. The Qing, beginning in 1740, used Buddhism to control the Mongols by determining that the Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu was to be found only in Tibet to ensure that the temples would not become a place of rebellion. At the same time, the monasteries were given a Da Lama, who was usually a Manchu, to oversee the activities of the monastery. At the beginning of the 20th century, about 40% of the men were lamas or laymen in the monasteries, of which there were more than 800 throughout Mongolia. The monasteries possessed great economic power and had accumulated large fortunes.

From the 1920s onwards, all religions were fought on the Soviet model. Many monasteries and temples were destroyed, including Erdene Dsuu in 1937, and thousands of lamas were murdered or exiled. Only a few monasteries survived the socialist period. Nevertheless, certain traditions, such as Buddhist burial, were not touched. After democratization in 1991, however, the practice of religion revived strongly. In 2007 there were about 100 temples and monasteries, although a certain part of the population is sceptical about religion.

Due to the lack of official religious statistics and the unquantifiable overlap between Lamaism and shamanism, no reliable figures are known. Thus, 50 to 96 percent of the population is reported to be Buddhist. The religious studies database Association of Religion Data Archives gives 54.2 percent Buddhist and 18.6 percent ethnic religions.

Most of the Turkic peoples living as minorities in Mongolia, such as the Kazakhs living predominantly in the Bajan-Olgii Aimag, are followers of Islam, with the exception of the Tuvins. They make up about five percent of the total population.

At the beginning of the 20th century there were first missionary efforts by European and American priests for Christianity, but the missionaries were deported when the Soviets took power. The end of socialism also meant the return of missionaries, especially from Protestant denominations. According to surveys, one to seven percent of the population describe themselves as Christians, with Christianity often associated with the high Western standard of living. The Catholic Church in Mongolia is also becoming increasingly popular.

Education

Before the overthrow of 1921, education in Mongolia was almost exclusively the domain of Buddhist monasteries. Only a small percentage of the population had access to education, so only monks and government officials were literate. The socialist government subsequently introduced a universal and free education system, on which it spent about one-fifth of the budget. In the 1930s schools were built in all the major permanent settlements in the country, usually with a dormitory attached for children of nomadic families. In the 1940s, the traditional Mongolian script was abolished and a new Cyrillic alphabet was introduced, which meant that adults had to learn to read and write once again. The successes of socialist education policies continue to have an impact today, and Mongolia now has one of the highest literacy rates in the world: 97.8% of the population can read and write. In Mongolia today, children start school at the age of seven. Schooling is compulsory for eight years, and every year around 120,000 pupils start higher education.

After the fall of communist rule, foreign donors demanded that the new government cut spending on education and introduce school fees. This led to a deterioration of conditions in the schools, teachers no longer received their salaries and the proportion of school dropouts increased. Especially boys leave school earlier to go to work.

The first university of Mongolia was founded in 1942. Today, under the name National University of Mongolia, this institution is the leading academic educational institution in the country. By splitting off from the State University, other specialized universities and institutes were established over time. Since democratization, numerous private universities and vocational schools have also been established. Although they were accepted by the population only hesitantly, today they offer an alternative to state institutions. Finally, by the end of 2008, there were 31 state universities and 55 officially accredited private academic educational institutions. Until the 1980s, numerous Mongolians studied in the Soviet Union, the GDR or other states of the Eastern Bloc; today, they are oriented towards East Asia, Europe and North America.

Monastery Amarbajasgalant in the north of Mongolia

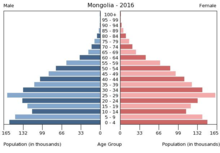

Mongolia population pyramid 2016

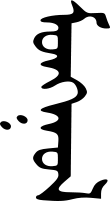

The word "mongol" (mongɣol) in Mongolian script.

An Oboo (Ovoo) in the northwest of Mongolia

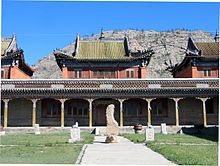

Monastery facilities in Erdene Dsuu

Tsetserleg Monastery

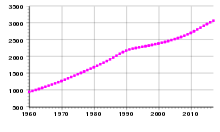

Population development of Mongolia from 1960 to 2017 (data from FAO)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the political system in Mongolia?

A: The political system in Mongolia is a parliamentary republic.

Q: What percentage of the population lives in Ulaanbaatar?

A: About 38% of the population lives in Ulaanbaatar.

Q: How many people live in Mongolia?

A: There are 2,791,272 people living in Mongolia.

Q: What is the size of Mongolia compared to other countries?

A: Mongolia is the 18th biggest country in the world, with an area of 1,564,116 km2 (603,909 sq mi).

Q: Are most Mongolians nomads or do they stay in one home?

A: Most Mongolians were traditionally nomads (people who always move from place to place and do not stay in one home), but this is changing.

Q: Is there a lot of mountainous terrain in Mongolia?

A: Yes, there are many mountains located mainly in the north and east parts of the country.

Q: Is there any desert land within Mongolia's borders?

A: Yes, part of the south part of Mongolia is made up by Gobi Desert.

Search within the encyclopedia