Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The British monarchy is the parliamentary monarchy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The current monarch, since 6 February 1952, is Queen Elizabeth II, and she and her immediate family perform various official, ceremonial and representative functions. Although the Queen theoretically has the powers of a constitutional monarch, she no longer exercises her sovereign rights independently due to a centuries-old customary law, but exclusively according to the instructions of Parliament and the Government. For this reason, it is a de facto parliamentary monarch. Even the existence of the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands does not change this status, because they are not legally part of the United Kingdom.

Around the year 1000, the kingdoms of England and Scotland had developed from several small early medieval kingdoms. The rule of the Anglo-Saxons ended in 1066 during the Norman Conquest of England. In the 13th century, England absorbed the principality of Wales, and the Magna Carta began the process of gradually removing the monarch from power. In 1603, the Scottish king James VI ascended the English throne as James I, thus ruling both kingdoms in personal union. From 1649 to 1660 there was a brief republican phase with the Commonwealth of England. The Act of Settlement, passed in 1701 and still in force today, excluded Catholics or those married to Catholics from succession to the throne. In 1707, England and Scotland joined together to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. The union with the Kingdom of Ireland created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.

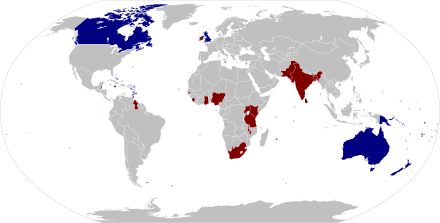

The British monarch was the nominal head of the British Empire, which at the time of its greatest expansion covered a quarter of the land area of the earth. In 1922, the Irish Free State seceded, in which the monarch remained head of state until 1949. With the end of the British Empire after World War II, the British monarch assumed the ceremonial title of head of the Commonwealth of Nations, a loose union of the United Kingdom and the former colonies. Fifteen independent states, known as Commonwealth Realms, continue to share the same head of state with the United Kingdom. However, each of these states forms a legally separate kingdom.

The office and its meaning

Constitutional and political role

The monarch has a high symbolic value as a "sign of national unity" and is the head of state under the unwritten British constitution. Oaths of allegiance are taken to him and his legitimate descendants, not to Parliament or the nation. God Save the Queen (or God Save the King in the case of a male monarch) is the British national anthem. In addition, the portrait of the monarch appears on stamps, coins and banknotes.

In practice, the monarch's political powers are severely limited by laws, customary laws and precedents. Whereas in the past the monarch had the power to issue his own decrees, conclude international treaties or declare war, even without regard to Parliament, nowadays he may exercise these sovereign powers only in accordance with the Council and with the consent of the Prime Minister or other ministers. Thus acts of state in the name of the Crown, even when made by the monarch personally, are subject to decisions made by others. This right is often used by the government to legislate past Parliament, as when Britain joined the European Economic Community or declared war in the Falklands War. The extent to which these rights may extend is controversial - and was the subject of political debate in the case of Brexit, for example.

The monarch's independent constitutional powers have thus been limited for the most part since the 19th century to impartial functions such as honours. In his 1867 work The English Constitution, the constitutional theorist Walter Bagehot referred to the monarchy as the "dignified part" of the state, while the government and parliament were the "working part". Whether and to what extent the monarch can or should actually exercise his rights to rule in exceptional circumstances is debatable. Any unconsented action of this kind has the potential to trigger a constitutional crisis.

Whenever necessary, the monarch is responsible for appointing a new prime minister and all other ministers. The latter is done on the proposal of the Prime Minister, who thus controls the government. In accordance with unwritten common law of a constitutional nature, the monarch must appoint the person who has the support of the House of Commons, usually the leader of the majority party. The Prime Minister takes office in a private audience with the monarch; this process is also known as kissing hands.

If no party achieves an absolute majority, which is rare in the British first-past-the-post system, two or more parties form a coalition, which then agrees on a candidate for prime minister. If no agreement is reached, this theoretically increases the choices available to the monarch. Nevertheless, it is customary to select a member of the largest party. The monarch can theoretically dismiss the prime minister, but in practice the prime minister's term ends only through electoral defeat, loss of a majority in parliament, resignation or death.

Sovereign rights

The executive power of the Crown is described by the collective term Royal Prerogative. Because of the many restrictions, the monarch exercises his sovereign powers exclusively on the advice of ministers who are responsible to Parliament. In most cases it is the Prime Minister or the Privy Council, the latter now controlled by the Cabinet. The monarch meets weekly with the Prime Minister. He is entitled to express his opinion, but must ultimately accept the decisions of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (assuming they have a majority in the House of Commons). According to Walter Bagehot, in a constitutional monarchy the monarch has three rights, "the right to be heard, the right to encourage, and the right to warn."

Although sovereign powers are extensive and do not require the consent of Parliament to be exercised, they are nevertheless limited. Many sovereign powers are no longer exercised, have effectively passed to the Prime Minister, or have been permanently transferred to Parliament. For example, the monarch is not permitted to levy and collect new taxes. Such action mandatorily requires the approval of Parliament. According to a 2002 parliamentary report, "the Crown cannot introduce new sovereign powers" and Parliament can repeal any sovereign powers by passing an Act.

It is the sovereign right of the monarch to convene, prorogue and dissolve Parliament. Each parliamentary session begins with the summoning by the monarch. This is followed by the State Opening of Parliament, when he delivers the Speech from the Throne in the Chamber of the House of Lords, announcing the government's legislative objectives. The prorogation usually happens a year after the start of the session and formally ends it. The dissolution, which ends a parliamentary term, is followed by elections for all seats in the House of Commons. The timing of the dissolution is influenced by several factors. For example, a parliamentary term may not exceed five years, in which case dissolution is automatic under the Parliament Act 1911.

As a rule, however, the prime minister chooses that moment which promises the most favourable prospects for his party. Under the Lascelles Principles (named after Alan Lascelles, George VI's private secretary), established in 1950, the monarch can theoretically refuse to dissolve parliament, but the conditions under which such action would be justified are unclear. The formal assent of the monarch (Royal Assent) is required before any law passed by both Houses of Parliament can come into force. In theory, the monarch can give or withhold his assent, but the latter has not happened since 1707, when Queen Anne repudiated a law on civil guards in Scotland.

There is a similar relationship with the regional governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The monarch appoints the First Minister of Scotland in accordance with the nomination of the Scottish Parliament and the First Minister of Wales in accordance with the nomination of the Welsh Parliament. In matters affecting Scotland, he acts on the advice of the Scottish Government. As autonomy in Wales is less extensive, in Welsh matters the monarch acts on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. The monarch can veto any legislation passed by the Northern Ireland Assembly if the Northern Ireland Secretary considers it unconstitutional.

In theory, the monarch can regulate the administration of the state, issue passports, declare war, make peace, lead troops, and negotiate and ratify treaties, alliances and international agreements. However, an agreement may not affect laws of the United Kingdom, in which case an Act of Parliament is required. However, the right to inspect draft legislation and, in the case of draft legislation affecting the private interests of the British royal family, to influence the drafting of legislation in advance is guaranteed to the holder of the throne and successor to the throne by the Queen's Consent.

The monarch is commander-in-chief of the armed forces, consisting of the British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. He accredits ambassadors and high commissioners and receives foreign diplomats.

The monarch is called the "fount of justice". However, he is not personally present in court cases, instead all legal activities are carried out in his name. Common law states that he can do no wrong and therefore cannot be charged with a crime in his own name. The Crown Proceedings Act 1947 allows civil actions against the monarch in his public capacity (that is, against the government). Actions against the monarch as a private individual, on the other hand, cannot be brought in court. The monarch also exercises the 'prerogative of mercy' and can grant pardons or reduce sentences.

As the fount of honour, the monarch also bestows all the honours and dignities of the United Kingdom. The Crown creates all titles of nobility, appoints all members of orders of chivalry, grants all knighthoods and other honours. Although titles of nobility and other honours are conferred in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister, some honours are considered a personal gift from the monarch. Accordingly, he has sole authority to appoint members of the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle, the Royal Victorian Order and the Order of Merit.

The Great Seal of the Realm is used to authenticate important official documents, including letters patent, proclamations and writs of election. The Great Seal of the Realm is in the custody of the Lord Chancellor. For matters relating only to Scotland or Northern Ireland, the Great Seal of Scotland and the Great Seal of Northern Ireland are used respectively.

Role in the Commonwealth

The British monarch is the monarch not only of the United Kingdom but also of 15 other Commonwealth Realms. Although his constitutional rights in each of these countries are virtually identical to those in the United Kingdom, he does not exercise any political or ceremonial functions as head of state there. Instead, a Governor-General represents him. In each country, the Governor-General acts solely in accordance with the advice of the respective Prime Minister and Cabinet. Consequently, the government of the United Kingdom also exercises no influence over the policies of Commonwealth Realms. Current Commonwealth Realms, in addition to the United Kingdom, are: Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, Canada, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tuvalu.

At one time, every member state of the Commonwealth of Nations was also a Commonwealth Realm. However, when India chose the republic as its form of government in 1950, it nevertheless remained a member of the Commonwealth, even though the British monarch is no longer the head of state. Since then, he has been considered the "Head of the Commonwealth" (Head of the Commonwealth) in all member states, whether he is the Head of State or not. This position is purely ceremonial and does not involve any political power.

The British monarch is directly responsible for the Crown Dependencies that are not part of the United Kingdom. In the Channel Islands he bears the title Duke of Normandy and is represented in the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey by a Lieutenant Governor. In the Isle of Man, he bears the title Lord of Mann, and is also represented there by a Lieutenant Governor.

Religious role

The British monarch is the head (Supreme Governor) of the Church of England, the official state church of England. As such, he has the right to appoint archbishops and bishops - on the advice of the Prime Minister, who selects from a list of names compiled by the Church's Nominations Committee. The monarch's role is limited to that of church patron. The senior cleric, the Archbishop of Canterbury, is the spiritual head of the Church of England and of all other Anglican churches. In the Church of Scotland the monarch is an ordinary member. However, he has the right to appoint the Lord High Commissioner of the General Assembly. In the Church in Wales and the Church of Ireland the monarch has no formal role, neither being a recognised state church.

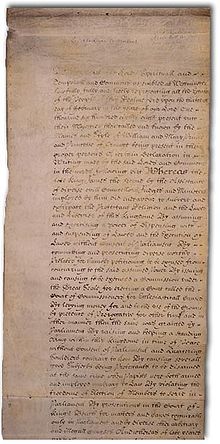

The English Bill of Rights of 1689 restricted the power of the monarch

The British monarch awards medals like the Order of Merit...

Today's Commonwealth realms Former Commonwealth realms

History

English monarchy

See also: List of the rulers of England and History of England

On the island of Britain there were already monarchs before the Roman invasion; these Celtic "reges" (Latin plural for "kings") allied themselves with the Romans or were subjugated by them. After the final retreat of the Romans at the beginning of the 5th century came the so-called Dark Centuries, the transition of Late Antiquity into the Early Middle Ages. Immigrating Angles, Saxons and Jutes pushed the Celtic tribes to the edges of the island. The peoples united to form the Anglo-Saxons established several kingdoms, the seven most powerful being known as the Heptarchy. Each kingdom had its own monarch and at times one of these kings was so powerful that he dominated the others. However, there was no "British monarchy" in the modern sense. Bretwalda was thus more of a prestigious honorary title with no actual power attached to it.

Following the raids of the Vikings and their subsequent settlement, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex rose to become the dominant English kingdom in the 9th century. Alfred the Great secured the supremacy of Wessex, gained control of western Mercia, and took the title of "King of the English". His grandson Æthelstan was the first to rule over a united kingdom whose boundaries roughly corresponded to those of modern England, although the various parts of the country retained a strong regional identity. In the 11th century England became visibly more stable, despite various wars with the Danes, who ruled for a generation. The Norman conquest of England in 1066 was a significant event both politically and socially. William I continued the centralization begun by the Anglo-Saxons, while the feudal system continued to develop.

William I was followed by two of his sons, William II and Henry I. The latter made a momentous decision by declaring Matilda, his only surviving child, heir to the throne. After Henry's death in 1135, his nephew Stephen asserted his claim to the throne. With the support of most of the barons, he came to power. Stephen's rule was weak, however, so Matilda was able to challenge him. England sank into a period of chaos, also known as "The Anarchy". Stephen clung to power, but compromised and accepted Matilda's son, later King Henry II. , as heir to the throne. The latter became the first ruler of the House of Plantagenet (also known as the House of Anjou) in 1154.

The reigns of most Plantagenet kings were marked by unrest and conflict between the monarch and the nobility. Henry II faced rebellions from his own sons, the later kings Richard I "Lionheart" and John. Nevertheless, Henry managed to expand his realm. Most notable was the conquest of Ireland, which had previously consisted of a number of competing kingdoms. Henry gave the island to his younger son John, who subsequently ruled as Lord of Ireland. After Henry's death, his elder son Richard succeeded to the throne, but he was out of the country for most of his reign and took part in the Third Crusade. He was succeeded by his brother John.

John's reign was marked by disputes with the barons, who pressured him into signing the Magna Carta in 1215, which guaranteed the rights and freedoms of the nobility. Soon after, further disputes led to a civil war known as the First War of the Barons. The war ended abruptly when John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son Henry III. The barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, later rose again against the king's rule, leading to the Second War of the Barons. This conflict ended in a clear victory for the royalists and the execution of numerous rebels. Earlier, in 1265, the king had agreed to convene the first parliament.

The next monarch, Edward I, was far more successful in maintaining royal power. He conquered Wales and extended English influence to parts of Scotland. However, his successor, Edward II, was defeated at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, after which the Scots won complete independence. Edward II was also involved in conflicts with the nobility. He was stripped of his power by his wife Isabella in 1327 and subsequently assassinated. His son Edward III claimed the French throne, triggering the Hundred Years' War.

Edward III's campaigns were mostly successful and led to the conquest of further French territories. Under his reign, Parliament also continued to develop, splitting into two chambers. In 1377 Richard II, his then ten-year-old grandson, succeeded to the throne. Like many of his predecessors, he was involved in conflicts with the nobility because he wanted to unite as much power as possible in one hand. When he led a campaign in Ireland in 1399, his cousin Henry Bolingbroke seized power. Richard was captured and murdered the following year.

Henry Bolingbroke, now King Henry IV, was the grandson of Edward III and son of John of Gaunt. For this reason his dynasty is known as the House of Lancaster. Throughout almost his entire reign, Henry was busy uncovering conspiracies and fighting rebellions. His success was largely due to the military prowess of his son, later King Henry V. The latter's reign began in 1413 and was largely free of internal conflict, allowing him to focus his attention on the still ongoing Hundred Years' War. He was successful militarily, but died unexpectedly in 1422, after which he was succeeded on the throne by his son Henry VI, who was then an infant. This gave the French the opportunity to shake off English rule.

The unpopularity of Henry's regents and his warlike wife Margaret of Anjou, and later his own ineffective leadership, resulted in a weakening of the House of Lancaster. Richard Plantagenet, head of the House of York and descendant of Edward III, asserted his claim to the throne, triggering the Wars of the Roses. Although Richard died in 1460, his son Edward IV led the House of York to victory in 1461. However, the Wars of the Roses continued throughout the reigns of Edward and his brother Richard III. Finally, in 1485, the conflict ended with the victory of the House of Tudor, a collateral line of the House of Lancaster, at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III was killed in battle; Henry Tudor ascended the throne as King Henry VII and founded the House of Tudor.

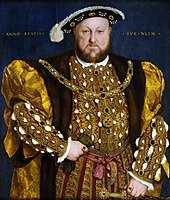

The end of the Wars of the Roses forms an important milestone in the history of the English monarchy. Most of the nobility had either fallen on the battlefield or been executed; many noble estates were lost to the royal house. In addition, the feudal system was disintegrating and the armies controlled by the barons were proving to be redundant. The Tudor monarchs were able to assert their absolute claim to rule and conflicts with the nobility came to an end. The power of the crown reached its peak under the reign of the second Tudor king, Henry VIII. England was transformed from a weak kingdom to a major European power. Religious tensions led to a break with the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church and the formation of the Church of England. Another milestone was the formal union of Wales with England between 1535 and 1542.

Henry's son, the young Edward VI, continued the Reformation. His early death in 1553 triggered a succession crisis. He had wanted to prevent his Catholic half-sister Mary I from taking power and named Jane Grey as his heir in his will, even though no woman had ever ruled the country before. Her reign, however, lasted only nine days. Mary, with the support of public opinion, deposed Jane Grey, revoked her proclamation as queen, had her rival executed, and proclaimed herself the rightful heir to the throne. Mary wanted to reintroduce the Catholic faith with all her might and had countless Protestants executed. After her death in 1558, Elizabeth I took the throne and returned England to Protestantism. Under her rule, England rose to become a world power, thanks to victory in the Anglo-Spanish War, the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588, and the colonization of North America.

Scottish Monarchy

→ See also: List of the rulers of Scotland, History of Scotland

When the Romans withdrew from the island of Britain, there were three main tribes in Scotland: the Picts in the northeast, the Britons in the south (including the Kingdom of Strathclyde), and the Gaels or Scots in the western Kingdom of Dalriada. In 843, the Scots king Kenneth MacAlpin assumed the Pictish crown. He is considered the founder of a united Scotland and the House of Alpin. Over time, the Scottish empire expanded as other territories such as Strathclyde were subjugated.

Early Scottish monarchs were elected according to Tanistry custom, causing different lines of the House of MacAlpin to succeed each other in power. As a result, there were often violent clashes between the rival lines of the dynasty. From 942 to 1005, there were no less than seven kings who were either assassinated or died on the battlefield. Malcolm II abolished the Tanistry system in 1005 and had numerous rivals eliminated, thus consolidating his position of power. His grandson Duncan I became Scotland's first hereditary monarch in 1034. In 1040 Duncan was killed in a battle by Macbeth, who in turn was killed in 1057 by Duncan's son Malcolm Canmore. After the murder of Macbeth's stepson Lulach, Malcolm Canmore ascended the Scottish throne as Malcolm III and founded the House of Dunkeld.

To make his victory possible, Malcolm had resorted to English aid, marking the beginning of a long era of English influence on Scottish politics. After his death in 1093, a series of succession wars ensued between Malcolm's sons on the one hand and Malcolm's brother Donald III on the other. From 1107 Scotland was briefly divided in two, in accordance with the last will of King Edgar. He had divided the kingdom between his elder son Alexander I. and his younger son David I.. After Alexander's death in 1124, David inherited the northern half of the realm and Scotland was reunited. David was succeeded in 1142 by Malcolm IV. William the Lion followed him in turn.

William reigned for 49 years from 1165, making him the longest reigning of all Scottish monarchs. He took part in the rebellion against the English King Henry II. However, the rebellion failed and William fell into English captivity. In order to gain his release, he had to acknowledge the English king as supreme liege lord. Richard I agreed to dissolve the agreement in 1189 and demanded a large sum of money in return to fund the Crusades. William died in 1214, and his son Alexander II and grandson Alexander III attempted to conquer the Outer Hebrides, which were still under the rule of Norway. During the reign of Alexander III, a Norwegian campaign into western Scotland failed in 1263 under Håkon IV. The Peace of Perth, concluded in 1266, confirmed Scottish rule over the Outer Hebrides and other disputed territories.

Alexander's unexpected death in 1286 triggered a widespread succession crisis. The English king Edward I, who had been appointed as arbiter, chose Alexander's three-year-old Norwegian granddaughter Margaret. When she died on passage to Scotland in 1290, 13 claimants asserted their claim to the throne. A court led by Edward I named John Balliol as successor. However, the English king treated him as a vassal and interfered in Scottish domestic affairs. When Balliol broke his oath of allegiance to England in 1295, Edward's forces conquered large parts of Scotland. For the first few years of the ensuing Scottish War of Independence, Scotland had no monarch until Robert the Bruce proclaimed himself king in 1306.

The Scots proclaimed their independence in 1320 with the Declaration of Arbroath, which England confirmed in 1328 with the Treaty of Edinburgh and Northampton. But only a year later Robert died and the English invaded Scotland again in 1332 to install Edward Balliol, the supposedly "rightful" heir of John Balliol, as monarch. After further warfare, Scotland regained its independence in 1336 under David II, son of Robert the Bruce.

David II was succeeded in 1371 by Robert II of the House of Stewart (later Stuart). Under his reign and that of his son Robert III, royal power declined steadily. When Robert III died in 1406, the country had to be ruled by regents, as his son James I had been captured by the English.

After paying a large ransom, James I returned to Scotland in 1424. To restore his authority, he took a very violent approach and had many of his opponents executed. James II continued his father's purge policy. James III died in a battle against rebellious Dukes in 1488, after which James IV ascended the throne.

In 1513, James IV wanted to take advantage of the absence of the English King Henry VIII and conquer England. However, his troops suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Flodden Field. The king and many senior nobles perished. Since James V's successor was still an infant, regents ruled the country. James V again waged a devastating war against England in 1542 and died in the same year. Heir to the throne was his six-day-old daughter Mary Stuart, again regents administered the country.

Catholic Mary ruled during a time of religious tension. Following the efforts of reformers around John Knox, Parliament determined that only a Protestant could lay claim to the Scottish throne. Mary married her Catholic cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, in 1565. After his murder in 1566, she entered into an even more controversial union with James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, widely believed to be Lord Darnley's murderer. The nobility revolted against the Queen and forced her to abdicate. She fled to England, and Elizabeth I had her imprisoned and later executed. The Scottish crown went to Mary's son James VI, who was still an infant and was raised Protestant.

Personal union and republican phase

The death of Elizabeth I in 1603 ended the reign of the House of Tudor, as she had no descendants. She was succeeded by the Scottish monarch James VI, who now ruled over England as James I as well. Although England and Scotland were linked in personal union (James I referred to himself as "King of Great Britain" from 1604), they remained separate kingdoms. James' son Charles I regularly engaged in conflicts with the English Parliament. These were over the distribution of power between the Crown and Parliament, and especially over the right to levy taxes. From 1629 to 1640, he ruled alone without ever summoning Parliament. Charles levied taxes on his own initiative and passed controversial laws, many of which were directed against the Scottish Presbyterians and the English Puritans. The conflict between royalty and Parliament reached its climax in 1642, when the English Civil War broke out.

The war ended in 1649 with the execution of the king, the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic known as the Commonwealth of England. In 1653, Oliver Cromwell, the most prominent military and political leader, seized power, appointed himself Lord Protector, and ruled as a kind of military dictator. He remained in power until his death in 1658 and was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell. The new Lord Protector showed little interest in governing and resigned after a short time. The lack of clear rule led to unrest and a desire to restore the monarchy spread among the people. The restoration took place in 1660 when Charles II, the son of the executed Charles I, was made king.

It was during Charles' reign that the forerunners of modern political parties were formed. The king had no legitimate children, so his Roman Catholic brother James, Duke of York was heir to the throne. There were moves in Parliament to exclude James from the succession. The "abhorrers" opposed the exclusion and formed themselves into the Tories, while the "petitioners" who favored exclusion formed themselves into the Whigs. However, the Exclusion Bill did not receive a majority. Several times Charles dissolved Parliament because he feared the Bill might be passed after all. After the dissolution of Parliament in 1681, he ruled as an absolutist monarch until his death in 1685. James II, a Catholic, pursued a policy of religious toleration, incurring the wrath of many Protestant subjects. Opposition arose to his decisions to create a standing army, promote Catholics to high political and military office, and arrest Church of England clerics who opposed his policies. As a result, a group of Protestant nobles invited James's daughter Mary II and her husband William III of Orange-Nassau to depose the king. William arrived in England on November 5, 1688, while James faced infidelity from numerous Protestant officials and fled. Parliament excluded James's Catholic son James Francis Edward Stuart from the succession. William and Mary were declared joint heads of state of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

The deposition of James has become known as the Glorious Revolution and was one of the most important milestones in the expansion of parliamentary power. The Bill of Rights, passed in 1689, confirmed the supremacy of Parliament and established that the English people possessed certain rights, notably freedom from such taxes as were levied without the consent of Parliament. The Act also required that future monarchs be Protestant. It also stipulated that only the children of William and Mary, or else Mary's sister Anne, could claim the throne. Mary died childless in 1694, making William sole monarch. In 1700, there was another crisis after all of Princess Anne's children died and she was now the only person in line to the throne. Parliament feared that James II or one of his Catholic relatives would again stake their claim and passed the Act of Settlement in 1701. A distant Protestant aunt of William, Sophie of the Palatinate, was designated heir to the throne. Shortly after the Act was passed, William died, making his sister-in-law Anne queen.

After the unification of the kingdoms

→ See also: History of the United Kingdom

After Anne's accession, the succession to the throne soon became a political issue again. The Scottish Parliament was angry that the English Parliament had arbitrarily declared Sophie of the Palatinate heir to the throne. It passed the Act of Security and threatened to dissolve the personal union of Scotland and England. The English Parliament in turn responded in 1705 with the Alien Act, threatening to collapse the Scottish economy by excluding it from free trade. As a result, the Scottish Parliament was forced to adopt the Act of Union in 1707. This Act united England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain, with the rules set out in the Act of Settlement continuing to apply to succession to the throne.

Anne, who died in 1714, was succeeded on the throne by George I, founder of the House of Hanover and son of Sophie of the Palatinate, who had also died a few weeks earlier. George consolidated his position of power with the suppression of two Jacobite uprisings in 1715 and 1719. The new monarch was far less active in governmental affairs than most of his predecessors, preferring instead to devote himself to the administration of his German possessions. This resulted in a shift of power to ministers, particularly Robert Walpole, who is considered Britain's first prime minister. The increase in power of the Prime Minister and his cabinet continued under the reign of George II. In 1746, the Catholic Stuarts were finally defeated. Under George III, the American colonies were lost, but in the rest of the world British influence increased. The Act of Union in 1800 created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

From 1811 to 1820 George III was insane and his son, later King George IV, ruled in his place as Prince Regent. During the regency, and later during his own reign, the king's power steadily declined. His successor, William IV, was no longer able to effectively limit the power of Parliament. After political differences, he dismissed William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, the prime minister of the Whig party, in 1834 and appointed Robert Peel of the Tory party instead. The King had no choice but to reinstate Lord Melbourne, as the Whigs won the subsequent election. Since then, no monarch has appointed or dismissed a prime minister against the will of the democratically elected parliament. In addition, the Reform Act 1832 was passed, disappearing the many rotten boroughs. Further legislation gradually led to more electors and greater legitimacy for the House of Commons as the more important part of Parliament.

The final step towards a constitutionalmonarchy was taken during the long reign of Queen Victoria. Under the Lex Salica, she was not allowed to rule over the Kingdom of Hanover as a woman, ending the personal union of the United Kingdom with Hanover. The Victorian era was marked by rapid technological advancement and the rise of Britain as the leading world power, the British Empire. As a sign of British rule over India, the title of Empress of India was conferred on her in 1876. Republican movements gained momentum, partly in response to Victoria's continued mourning and prolonged withdrawal after the death of her husband Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1861.

Victoria's son Edward VII became the first monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1901. However, his son George V changed the family name to Windsor in 1917 due to anti-German sentiment among the population during World War I. In 1922, Ireland was separated into Northern Ireland (which remained part of the United Kingdom) and the independent Irish Free State. Five years later, the name of the state was changed to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

From empire to community of nations

Until 1926, the Dominions and Crown Colonies were subordinate to the United Kingdom. The Balfour Declaration gave the Dominions full rights of self-government. This gave the Dominions equal status with the mother country, effectively creating multiple kingdoms with the same monarch. The Statute of Westminster of 1931 confirmed this concept. George V was subsequently King of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and other states.

Edward VIII caused a scandal in 1936 when he wanted to marry the divorced American Wallis Simpson, although the Church of England rejected the remarriage of divorcees. He renounced the crown and abdicated. The parliaments of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth states granted his request. Edward VIII and any children of his new wife were excluded from the succession and the crown passed to his brother George VI. The latter remained at home during the Second World War and did not seek refuge in Canada from the events of the war, which led to a surge in popularity. George VI was also the last monarch to hold the title "Emperor of India" when India gained independence in 1947.

George VI was succeeded in 1952 by his daughter Elizabeth II, who still reigns today. During her reign, support for the republican movement increased at times, particularly because of the poor image of the British royal family caused by negative events such as the death of Princess Diana. However, more recent opinion polls show that loyalty to the monarchy continues unabated in wide swathes of the population. Elizabeth II was followed in first place by Prince Charles, then Prince William, his son George, then Charlotte and Louis Arthur Charles, a newborn on that day, according to the April 24, 2018 order of succession to the throne. Prince Harry slipped to sixth in line to the throne on that day.

Edward II

Henry VIII

Scottish royal flag

David I (left) and Malcolm IV.

James IV.

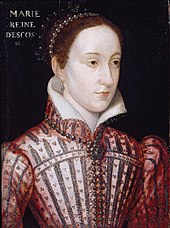

Mary Stuart

James VI (resp. James I) was the first monarch to rule over England, Scotland and Ireland.

James II.

Queen Anne

.jpg)

Edward VIII

Queen Victoria

Richard the Lionheart

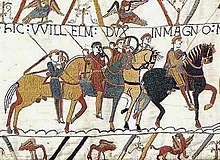

The Bayeux Tapestry Themes the Norman Invasion

George III.

Search within the encyclopedia