Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (born July 31, 1912 in Brooklyn, New York City; † November 16, 2006 in San Francisco) was a U.S. economist who wrote fundamental works in the fields of macroeconomics, microeconomics, economic history, and statistics. He received the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976 for his achievements in the analysis of consumption, the history and theory of money, and for his demonstration of the complexity of stability policy.

Along with George Stigler and others, Friedman is considered one of the intellectual leaders of the Chicago School of Economics, a neoclassical economic school that rejected Keynesianism in favor of monetarism. Beginning in the 1970s, New Classical Macroeconomics came to the center of the school, which drew heavily on the concept of rational expectations. Friedman's disciples include leading economists such as Gary Becker, Robert Fogel, and Thomas Sowell.

Friedman began his academic work with a critique of what he saw as a "naïve interpretation of Keynesian theory". This was already evident in his reinterpretation of the consumption function in the 1950s. During the 1960s he became one of the main opponents of Keynesian public policy. He once described his approach as "exploiting the Keynesian language and theoretical apparatus," but with the aim of criticizing the theory's usual conclusions. Friedman argued that there was a natural rate of unemployment. Attempts by the government to reduce unemployment to a level below this natural rate would lead to inflation. Furthermore, he posited that the Phillips curve is vertical on the natural rate of unemployment in the long run. Therefore, he argued, persistent deficit spending leads to stagflation in the long run. Friedman advocated monetarism, which calls for tight control of the money supply by the central bank to prevent inflation. His ideas regarding monetary policy, taxes, privatization, and deregulation were influential, especially in the 1980s. His monetary theory influenced the behavior of the Federal Reserve during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Friedman served as an advisor to US President Ronald Reagan and to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. He himself singled out the abolition of conscription in the United States as his greatest political achievement. Friedman, who considered himself a classical liberal, particularly pointed out the advantages of a free market and the disadvantages of government intervention. His basic stance is expressed in his best-selling Capitalism and Freedom (1962). In it, he called for minimizing the role of government to promote political and social freedom. In his television series Opportunities I Mean (Free to Choose), which PBS broadcast in 1980, Friedman explained the workings of the free market, emphasizing in particular that other economic systems could not adequately solve a society's social and political problems. Friedman took a liberal stance on drugs and prostitution and called for the liberalization of copyright law.

Friedman's oeuvre includes monographs, books, academic papers and publications, columns, television series, and lectures covering a wide range of economic and political topics. His works have had worldwide influence, especially in former socialist countries. A survey of economists found Friedman to be the second most influential economist of the 20th century, preceded only by John Maynard Keynes. The Economist called Friedman the most influential economist of the second half and perhaps the entire 20th century.

Live

Childhood and student days

Friedman was born in Brooklyn, New York City on July 31, 1912. His parents, Sára Ethel (née Landau) and Jenő Saul Friedman, were Jewish immigrants from Beregszász in Carpathian Ukraine, in what was then the Kingdom of Hungary, now Ukraine. Both worked as haberdashers. Shortly before his birth, the family moved to Rahway, New Jersey.

In his teens, Friedmann was injured in a car accident, leaving a scar on his upper lip. In 1928, he graduated from high school just before his 16th birthday and began studies in mathematics and economics at Rutgers University in New Jersey. His academic teachers included Arthur F. Burns and Homer Jones, who convinced him that modern economics could help end the Great Depression.

Friedman graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1932 and initially planned a career as an actuary. However, he received offers of graduate fellowships, one for mathematics at Brown University and another for economics at the University of Chicago. Friedman chose Chicago and earned a Master of Arts degree in 1933. At Chicago he was greatly influenced by economists such as Jacob Viner, Frank Knight, and Henry Simons. It was at Chicago that he met his future wife Rose Director, who was also studying economics.

During the academic year 1933-1934 he had a fellowship at Columbia University where he heard statistics with Harold Hotelling. By 1934 he was back in Chicago, working as a research assistant for Henry Schultz. That same year he formed a lifelong friendship with George Stigler and W. Allen Wallis.

Public service

Friedman was subsequently unable to find employment at the university. In 1935, he followed his friend W. Allen Wallis to Washington, D.C. , where he found employment through Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, he found employment. At the time, Friedman viewed New Deal programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and Public Works Administration (PWA) as appropriate policy responses to combat unemployment during the Great Depression. However, he criticized the wage and price controls enforced by the National Recovery Administration and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

In 1935 he began working for the National Resources Planning Board, an agency which at the time was researching a major survey of consumer behavior. Some of these ideas were reflected in his later text Theory of the Consumption Function. He assisted Simon Kuznets in his research on earned income. This collaboration resulted in the jointly published work Incomes from Independent Professional Practice, where the concepts of permanent and transitory income were introduced. The book hypothesizes that occupational restrictions such as professional licensing reduce the supply of services and thus increase prices for consumers. These considerations are an important component of the permanent income hypothesis that Friedman developed in the 1950s.

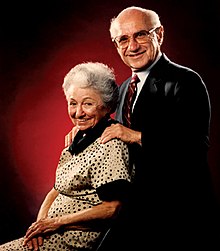

In 1938 he married the economist Rose Director. A daughter was born to them in 1943, and their son David in 1945, who later became a lawyer.

In 1940 Friedman obtained a position as assistant professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. There, however, he experienced anti-Semitism among the faculty, which is why he returned to public service in 1941.

In 1943 he went to Columbia University's Division for War Research, where his research was mostly on mathematical statistics, weapons design, and military tactics. Between 1943 and 1945, he also worked at the United States Treasury Department, where he advocated Keynesian fiscal policy as press secretary. He also helped develop the U.S. payroll withholding tax system, as the federal government needed revenue to finance the war.

Academic career

Friedman's dissertation, written jointly with Simon Kuznets, is entitled Income from Independent Professional Practice and addresses the economic situation of members of the liberal professions. He completed it in 1940, submitted it in 1945, and received his doctorate in 1946.

In 1946, Milton Friedman began teaching at the University of Chicago, a position he held for 30 years. The position became vacant because one of Friedman's former teachers Jacob Viner received an appointment at Princeton University. During this period, the name Chicago School was formed for a research community that over the years produced several recipients of the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

Friedman attended the founding meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS) in April 1947. Friedrich von Hayek had invited him and 35 other scholars close to liberalism - economists as well as philosophers, historians and politicians. Friedman was president of the MPS from 1970 to 1972.

Friedman spent the academic year 1954-1955 as a Fulbright Visiting Fellow at Gonville andCaius College, Cambridge. At the time, the economics faculty was divided between a Keynesian majority (e.g., Joan Robinson and Richard Kahn) and an anti-Keynesian minority (Dennis Robertson). Friedman speculated that he received the Fellowship invitation because his views were unacceptable to both factions.

In the 1950s, he studied John Maynard Keynes's theory of demand policy. His engagement with Keynes culminated in the 1957 book A Theory of the Consumption Function, published by Princeton University Press. This challenged traditional Keynesian assumptions about households. It analyzed the relationship between aggregate consumption, aggregate saving rate, and aggregate income. Keynes assumed that households would relate their consumption expenditure to their income levels. Friedman introduced the concept of permanent income, which was the average of a household's income over several years. This is closely related to Friedman's permanent income hypothesis. The work changed the way economists interpreted the consumption function and promoted the idea that households did not make consumption decisions based only on their current income. Instead, they would make them contingent on current and future expected income levels. Furthermore, Friedman's theory provided predictions regarding the phenomenon of consumption smoothing, which contrasts with Keynes marginal consumption rate.

In 1957 Friedman was elected to the American Philosophical Society, in 1959 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 1973 to the National Academy of Sciences. In the 1970s, his supply-side economic theory competed with the Keynesian model. According to Gerhard Willke, Friedman, along with Friedrich von Hayek, was "the pioneer and master thinker of the neoliberal project," an economic policy project to achieve more market, more competition, and more individual freedom. Friedman did not, however, describe himself as a neoliberal.

His major work is considered to be A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, published in 1963, which he wrote with the economist Anna Schwartz. In it Friedman described the major effects of changes in the money supply on business cycles and thus disputed the Keynesian explanation of the Great Depression. According to Friedman, this was due not to private sector instability, but to the Federal Reserve System's reduction in the money supply. Friedman subsequently became known to a wide audience through popular scientific treatises, especially the book Capitalism and Freedom, published in 1963. He was also a columnist for Newsweek magazine in the 1960s/1970s. In 1967, Friedman also presided over the American Economic Association as president-elect. In the 1980s, Friedman and his wife created several television programs on economic topics (titled Free to Choose).

Friedman was also involved in policy decisions. For example, in 1971, after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the US government under President Nixon abolished the fixed exchange rate of the US dollar against other currencies on his advice. The economic stabilising effect predicted by Friedman soon materialised.

Pension

Friedman retired in 1977 at the age of 65 after teaching for 30 years at the University of Chicago. His wife Rose and he moved to San Francisco, where he was a visiting lecturer at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. He also worked with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. In the same he was contacted by the Free To Choose Network and asked if he would like to produce a television series about his economic and social philosophical ideas.

The Friedmans worked on the project for over three years, and in 1980 the ten-part series Free to Choose was broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). The companion book, co-written by Milton and Rose Friedman and also titled Free to Choose, was the #1 non-fiction bestseller of 1980 and has since been translated into 14 languages.

Friedman also worked as an unofficial advisor to Ronald Reagan during his campaign for the presidency of the United States. After Reagan's election, he became a member of the President's Economic Policy Advisory Board. In 1988, he received the National Medal of Science and Reagan awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

According to a 2007 article in Magazine Commentary, Friedman's parents were moderate Jews, but his personal religiosity came to an end after a strongly religious period in his childhood. He described himself as an agnostic. Friedman wrote extensively about his life experiences, most notably in his 1998 memoir Two Lucky People, which he published with his wife Rose.

Friedman continued to comment on current economic events well into old age. For example, when the euro was introduced in 1999, he speculated that the next global recession would tear it apart.

Friedman died of heart failure at his home in San Francisco on November 16, 2006. During this time, he was still working as an economist. His last column in the Wall Street Journal was published one day after his death.

Rahway, New Jersey

Milton and his wife Rose Friedman

Milton and Rose Friedman

Friedman taught at the University of Chicago for 30 years...

Works

Science

See also: Friedman test (statistics) and quantity theory

Monetarism

→ Main article: Monetarism

Friedman's most important scientific contribution is to have rehabilitated the money supply as the decisive variable in the economic process and in monetary policy. Monetarism states that changes in the money supply have a major influence on the national income of an economy in the short run and regulate the price level, i.e. the inflation rate, in the long run. The objective of monetary policy must therefore be to control the change in the money supply in order to prevent inflation. Monetarism in this context refers to an economic view that is closely related to modern quantity theory. The origins of the theory can be traced back to well before Friedman, but he popularized and disseminated its modern form. Friedman himself coined the slogan: "Money matters".

In particular, in his book A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, published with Anna Schwarz in 1963, he attempts to establish the relationship between the money supply and economic activity in the United States. One of the major results of their research is the primacy of the money supply over investment and government spending in determining consumption and production. Friedman's empirical and theoretical work was designed to show that a change in the money supply affects output in the short run, but primarily affects the price level in the longer run. The effects of the monetary policy of the US central bank, the Federal Reserve (FED), were also examined.

Friedman believed that there was a close and stable link between the expansion of the money supply and the rate of inflation.

"Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

"Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

- Milton Friedman: Inflation: Causes and Consequences

With this quote Friedman turned against a variety of arguments that inflation was a result of cost pressures, or increases in wages or the price of oil. Instead, inflation is always an effect of too much expansion of the money supply.

He saw the essential function of the central bank in controlling the money supply. In times of crisis, he argued, the central bank must expand the money supply to prevent deflationary tendencies and unemployment. A Monetary History of the United States illustrates this with the behavior of the Federal Reserve during the Great Depression, which Friedman holds substantially responsible for the severe and prolonged course of the economic crisis. This is because the FED raised interest rates during the economic crisis, which led to a reduction in the money supply.

"The Fed was largely responsible for converting what might have been a garden-variety recession, although perhaps a fairly severe one, into a major catastrophe. Instead of using its powers to offset the depression, it presided over a decline in the quantity of money by one-third from 1929 to 1933 [...]"

"The FED was largely responsible for turning a forest and meadow recession, albeit a very severe one, into a major disaster. Instead of using its power, it was responsible for a one-third decline in the money supply between 1929-1933 [...]"

- Milton Friedman: Two Lucky People, p. 233

The chapter on the Great Depression was published as a separate book in 2002. In a speech, then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke admitted to Friedman and Schwarz that their analysis was correct and assured them that the central bank would act differently in the future.

Friedman introduced the idea of helicopter money to combat severe recessions in a 1969 essay on a thought experiment.

Foreign exchange markets

Friedman argued for an end to government intervention in the foreign exchange market and advocated a system of freely floating exchange rates.

Consumption function

→ Main article: Permanent income hypothesis

Friedman was also known for his work on the consumption function, especially his permanent income hypothesis. He himself describes it as his best scientific work. The work is closely related to the theory of rational expectations. The hypothesis states that rational consumers would spend a proportionate share of what they see as their permanent income. Market position gains would be saved. The same is true for tax cuts, since rational consumers will predict that taxes will have to be raised again later to rebalance government budgets.

Unemployment

→ Main article: Natural rate of unemployment

See also: Phillips curve

Friedman also worked on unemployment and the Phillips curve. Friedman's theory of the natural rate of unemployment postulates a "natural rate of unemployment" for every economy, which is determined by the institutional conditions: frictional and structural factors as well as market imperfections such as lack of information, obstacles to mobility, adjustment costs and demographic change. In the long run, however, the rate of natural unemployment can be reduced by structural reforms. In the ideal case, i.e. in a perfect market, it would be zero.

Friedman argued that the natural rate of unemployment can be derived directly from the Phillips curve. This predicted that wages begin to rise when unemployment is low. Friedman argued that inflation was the same as wage increases and showed that the state could not reduce unemployment in the long run through expansionary demand policies.

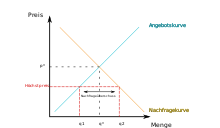

Rent control

→ Main article: Rent control

In 1946, Milton Friedman and George Stigler pointed out that rent controls were an inappropriate tool for creating affordable housing. Rent controls, like all price controls, would lead to shortages and scarcity. Landlords would convert their rental properties into condominiums in order to continue to maintain the market rate. Thus, the supply would continue to drop.

In addition, there would be coordination problems, as tenants in rent-controlled apartments would have no incentive to leave them if their housing needs changed. This misallocation could lead to households without children continuing to live in family housing and young families being crammed into small studios, which is an inefficient allocation.

Friedman Doctrine

→ Main article: Friedman Doctrine

Friedman has worked in the field of business ethics. He argues that the primary responsibility of a company lies with its shareholders. The owners are the only group for which the company is socially responsible. Therefore, companies should maximize shareholder returns.

Friedman captured the doctrine in the catchy slogan: "The Business of Business is Business."

Friedman argues in the essay that managers are hired to run a business for business reasons. Therefore, it is not their job to support social causes. This is because whenever a manager spends money, it is other people's money: either the owners' money, the employees' money, or the customers' money. According to Friedman, these groups should donate to social causes if they wish to do so, not the managers.

The Friedman Doctrine was supported by an influential paper by William Meckling and Michael Jensen. There, the authors present a quantitative economic rationale for the Friedman Doctrine.

The Friedman Doctrine has had a major impact on the business world.

Epistemology

Friedman contributed to the epistemology of his discipline. In his 1953 essay The Methodology of Positive Economics, he takes issue with Paul Samuelson's logical empiricism, which dominated economics at the time. Friedman argues for an instrumentalist position, i.e. he believes that scientific theories are created to solve problems in economics. Consequently, there is no question about the realism of the assumptions on which they are based: theories are instruments. They need not therefore be based on "true" or "realistic" hypotheses arising from an observation of reality, as long as they succeed in making predictions. For Friedman, therefore, the criticism of the lack of realism of the founding postulates of economics, such as the rationality of actors, is irrelevant insofar as only the instrumental value of these hypotheses matters. That is, if they are the basis of theories with accurate predictions, their use is justified.

This position represents the methodological foundation of the Chicago School.

Public intellectual

Capitalism and freedom

→ Main article: Capitalism and freedom

As a representative of economic liberalism, the freedom of the individual was central to Friedman's argument. He considered the free choice of the individual more beneficial than state regulation. Therefore, he supported a reduction of the state quota, free exchange rates, the elimination of state restrictions on trade, the removal of restrictions on access to certain professions, and a reduction of state welfare. Friedman also posited the luxury-good hypothesis of money.

He described the functions of the state as follows:

"A state that maintained law and order, defined property rights, served as a medium through which we could change property rights and other rules of the economic game, settled disputes over the interpretation of the rules, enforced the performance of contracts, fostered competition, provided a monetary constitution, engaged in activities to counteract technical monopolies and manage such neighborhood effects as are widely considered sufficient to justify state intervention, and which complemented private charity like the family in seeking to protect the incapable, whether mentally handicapped or child - such a state would clearly have important functions to fulfill.“

- Milton Friedman

Murray Rothbard, in the 1971 essay Milton Friedman Unraveled, concludes that it is difficult to view Friedman as an advocate of free market economics.

Opportunities I mean

→ Main article: Opportunities I mean

In Rose and Milton Friedman's work Opportunities I Mean (1980), he calls the welfare state and inflation the greatest enemies of the economy.

For Friedman, the welfare state is a fraud on the people who still work and pay taxes. For this he showed the methods in which money is spent:

- spend your own money on yourself, for example when shopping in the shoe store

- spending your own money on others, which happens especially at Christmas

- Spending other people's money on yourself by dining out or taking taxis on the company's dime

- spending other people's money on others, which is mainly what the welfare state does

For him, there is a clear gradient between the methods from one to four. The recklessness with which people handle money clearly increases from one to four. For Friedman, methods three and four are the reason for inflation and the cause of the decline of the Western industrial nations. Claiming to support the poor, the welfare state with its powerful welfare bureaucracy pulls money out of the pockets of the man in the office and at the workbench. But if you divide the amount of money spent to fight poverty in the U.S. until shortly before 1980 by the number of people who are needy according to official statistics, the income of these needy people would have to be one and a half to twice the average income of the population. In reality, there would be little left over for the needy. Because the money is mainly used for bureaucracy and personnel costs.

Microeconomic model for rent control: A maximum price below the market price (p*) leads to excess demand (scarcity), since more housing is demanded (q2) than is offered (q1).

Headquarters of the American FED: Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Milton Friedman?

A: Milton Friedman was an American economist who believed in monetarism, the theory that how much money the government prints each year has a huge effect on the economy.

Q: Where was he born?

A: He was born in Brooklyn, New York to a Hungarian-Jewish family and raised in Rahway, New Jersey.

Q: What universities did he attend?

A: He studied at Rutgers University, at Columbia University, and at the University of Chicago.

Q: What were his political views?

A: His political views were libertarian. He supported cutting taxes, lowering government spending, getting rid of government rules that limited the economy and letting parents choose which school their taxes paid for. He was also against forcing people to join the army.

Q: What are some of his most famous works?

A: Some of his most famous works include Capitalism and Freedom and Free to Choose as well as several documentaries, books, and interviews expressing his views to the public.

Q: Who did he marry?

A: He married Rose Director in 1938 and they had one son and one daughter together.

Q: How did he die? A: He died of heart failure in San Francisco California aged 94 and his remains were cremated and scattered over the San Francisco Bay area.

Search within the encyclopedia