Migration Period

![]()

This article is about the migration of peoples in late antiquity. For (peoples') migrations in general, see sociology of migration.

In historical research, the so-called migration of peoples in the narrower sense is the migration of mainly Germanic groups in Central and Southern Europe in the period from the invasion of the Huns into Europe circa 375/376 to the invasion of the Lombards into Italy in 568. The Migration Period falls within Late Antiquity and forms a link between Classical Antiquity and the European Early Middle Ages for the history of the northern Mediterranean region as well as Western and Central Europe, since it can be attributed to both epochs.

However, the migration of peoples in late antiquity does not represent a uniform, self-contained process. Rather, various factors played a role in the migratory movements of the mostly heterogeneously composed groups, whereby in recent historical and archaeological research many aspects of the migration of peoples are evaluated extremely differently. Central to the discussion are the questions of whether the collapse of the Western Roman Empire was a consequence or rather a cause of the "migrations of peoples" and whether "peoples" were actually wandering at the time or rather warrior groups in search of booty and supplies (annona). In modern research, the term "migration of peoples" is increasingly used critically, since according to today's assessment, the image of "migrating peoples" is not tenable and is now considered by many scholars to be refuted (see also ethnogenesis), or the idea of a migration of peoples is basically rejected as a "research myth".

Mainly, but not exclusively, affected by the events was the western half of the Roman Empire, de facto divided since 395. From 382 onwards, treaty arrangements (foedera) between the Roman imperial government and groups such as the Visigoths were increasingly frequent, resulting in the settlement of these warriors on Roman territory. In the internal conflicts that plagued Western Rome from 395 onwards, such fighting units were used with increasing frequency. Franks were also settled on Roman soil and, as foederati, took on tasks such as border protection in northeastern Gaul. After the crossing of the Rhine in 406 and the invasion of the western empire by the Vandals and Suebi, a possible breakdown of the Roman administrative order in Europe became apparent for the first time in Gaul.

Western Rome sank into long civil wars, the course of which at least partly conditioned the movements of the warrior units, as they were prominently involved in the battles. At the same time, the authority of the imperial government in Ravenna visibly deteriorated, and more and more political power passed to - Roman and Germanic - military leaders, whom today's research often refers to as warlords. In connection with this process, the Western Roman Empire came to an end in 476/80, while the Eastern Roman Empire survived the 5th century largely intact. On the soil of the disintegrated Western Empire, Germanic-Roman successor empires emerged in the 5th and 6th centuries, which were to decisively shape the culture of Europe in the Middle Ages.

Spangenhelm from the 6th century, import from eastern roman workshops

Germanic migratory movements before the invasion of the Huns

Even before the beginning of the actual "migration of peoples", there had been migratory movements of Germanic groups in the extra-Roman Barbaricum. The population east of the Rhine and north of the Danube aspired to a share of Roman prosperity, and Germanic warriors were faced with the choice of either undertaking risky plundering expeditions or placing themselves in the service of Rome instead. Apart from military conflicts, there were therefore also peaceful contacts. Trade was conducted along the Rhine border established under Tiberius, and Germanic tribesmen often served in the imperial army in order to gain Roman citizenship.

Nevertheless, we often only know about many migratory movements beyond the Roman horizon from mostly orally transmitted reports, which were later recorded in writing and are often mythically transfigured. Probably the best known of these origin stories, a so-called Origo gentis, is the 6th century Gothic History (or Getica) of Jordanes. Contrary to his account that the Goths would have originated in Scandinavia, current evidence suggests that they either moved from the area on the Vistula towards the Black Sea in the 2nd century AD or did not emerge until the 3rd century in the course of an ethnogenesis on the Danube. A fragment of a 3rd century Greek historical work published in 2014 (presumably part of the Scythian of Dexippus) mentions a Gothic leader (archon) named Ostrogotha already for the years around 250. What this means for the reconstruction of the origin of the Ostrogoths is still unclear. According to traditional readings, the Goths caused the first major migration, pushing the Vandals and Marcomanni southward and the Burgundians westward. These population shifts were one of the triggers for the Marcomannic Wars, in which Rome had difficulty in controlling the Germanic tribes. In the 50s and 60s of the 3rd century, when Rome was struggling with the symptoms of the imperial crisis and its defences were weakened by civil wars, Gothic and Alamannic groups repeatedly advanced on the soil of the empire, plundering.

In today's research, however, it is disputed how extensive and significant these migratory movements were. There are many indications that the new tribal associations of the Franks, Alamanni, Saxons, etc. formed only around 200 AD in the course of ethnogenesis in the immediate vicinity of the Roman provinces. While this view is shared by most researchers today with regard to the above-mentioned associations, in the case of the Goths, as already mentioned, it is disputed whether they had migrated to the Danube region or only formed there.

Around 290, the Goths probably divided into Terwingen/Visigoths and Greutungen/Ostrogoths. The Greutungen/"Ostrogoths" settled in the Black Sea area of today's Ukraine. The Terwingen/"Visigoths" settled first on the Balkan peninsula, in the area north of the Danube in today's Transylvania. The Tervingen came into direct contact with Rome, there were even military conflicts, but they were not decisive. In 332 the Danubian Goths received the status of foederati, i.e. they had to provide Rome with contractually guaranteed military assistance. The Gothic campaign is of particular interest because the subsequent development had lasting consequences for the Goths in particular: the Hun invasion around 375 (see below) not only drove many Goths out of their new homeland, but also set a process in motion through the subsequent movement of the Goths into the empire, as a result of which Rome had to fight for survival in the view of researchers such as Peter Heather (other researchers such as Guy Halsall, Michael Kulikowski or Henning Börm, on the other hand, attach far less importance to the events).

At about the same time as the Goths, Lombards migrated from the Lower Elbe to Moravia and Pannonia. Smaller incursions into Roman territory during this period were either repulsed or ended with minor border corrections. Further west, the tribal confederation of the Alamanni broke through the Roman border fortifications, the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, in the 3rd century and settled in the so-called Dekumatland after the Romans had cleared the area (Limesfall). Many gentes were also deliberately settled at the borders of the empire as confederates and formed buffers to more hostile tribes (see Foederates).

Rome had learned from the Germanic invasions and the civil wars of the 3rd century and had undertaken comprehensive military reforms in the early 4th century. Importantly, since the founding of the Persian Sassanid Empire, Rome had to constantly reckon with threats on several borders; the fierce battles with the Persians tied up strong Roman forces and thus, according to some scholars, had made the Germanic invasions of the 3rd century possible in the first place. To counter this strategic dilemma, many scholars have assumed, the military capability of the empire had to be improved. The emperors Diocletian and Constantine the Great, who privileged Christianity in the empire (Constantine's Turn), therefore expanded the army of movement (comitatenses), took back the borders in the north on the Rhine and Danube, had numerous fortresses built and thus once again secured the borders in the north and east. The later emperor Julian was able to destroy a numerically superior Alamannic contingent in the battle of Argentoratum in 357. In spite of the difficulties Rome had to face in the 3rd century due to the formation of large gentile units such as the Alamanni and Franks and the simultaneous wars with Persia, it was still militarily equal to these advances.

Before 378, the military initiative was usually on the Roman side. But with the invasion of the Huns, the threat situation changed abruptly, at least according to researchers such as Peter Heather; at the same time, Rome had already reached the extreme of military capability and was therefore no longer able to react flexibly. This and the fact that the quality and size of the migrating gentes changed in the period that followed are traditionally regarded as the two most important features of the migration of peoples, distinguishing it from previous migratory movements despite the relatively vague term.

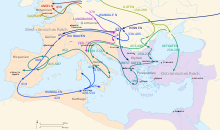

The conventional reconstruction of the so-called migrations of the second to fifth centuries

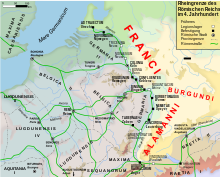

Northwestern Gaul and the Rhine and Danube borders of the Roman Empire at the time of Emperor Julian († 363)

View

According to the conventional view, the Longobard invasion of Italy marked the end of the great "migration of peoples". With this, a political order had emerged on the soil of the fallen Western Empire, which in large parts endured into the High and Late Middle Ages and was also to shape the modern world of states. After the collapse of the Carolingian rule, the Frankish Empire was transformed into the West and East Frankish Empires, the nuclei of France and Germany. During the Reconquista, the Visigothic empire was to have an identity-forming effect on the Spanish, and the Anglo-Saxons played a decisive role in shaping the image of the later kingdom of England, just as the Lombard empire, in a weakened form, was to have significance for Italy. In most of the regna that arose, in which Latin or vernacular Vulgar Latin eventually gained the upper hand (except in the special case of Britain), the new lords came to terms with the native population quickly and to a large extent, but in very different ways. It should be borne in mind that the Germanic warriors and their families were almost everywhere a vanishingly small minority compared to the Roman or Romanesque civilian population; one exception was probably northern Gaul.

Nevertheless, this should not obscure the sometimes dramatic changes at the end of Late Antiquity, which were not infrequently associated with acts of violence against the population. Although there was still a Roman Empire in the East with an emperor at its head, whose claim to leadership was at first generally respected, after Justinian's death (565) Eastern Rome no longer intervened to a comparable extent in the West, although the last Byzantine base in Italy did not fall until 1071. The period from the early 7th century onwards was then marked in the Eastern Empire by a permanent defensive struggle against Persians and Arabs, Avars and Slavs, which tied up almost all its forces. Thus the exarchates are also to be seen as a defensive measure. The Eastern Roman Empire, now almost completely Graecianized, transformed itself under Herakleios into the medieval Byzantine Empire.

In the west, the Roman army and the Roman administrative system had already disappeared by the 5th/6th century. Here, complex changes occurred in the order of rule as well as in the social and economic structure (see also the explanations in the article Late Antiquity). Despite the dramatic loss of ancient cultural goods (especially in the west), which is not necessarily related to the warlike conflicts of this period, many cultural elements were indeed preserved in the regna, although the level of education as well as literary production as a whole decreased significantly. Above all, the economy was now organized in a far less complex way than in Roman times, which led to significantly lower surpluses and a declining quality of material culture: Long-distance trade declined noticeably in the Migration Period, and likewise economic production in the regna was less organized around the division of labor than in Roman times. In the medium term, this led to a disappearance of the old civil elites, who had been the most important carriers of ancient education.

Church organization also changed, as the influence of the bishops increased in many places compared to the late Roman period. Thereby the church now functioned as an important carrier of ancient (Christian traditional) education, which was clearly below the ancient level, but also absorbed other influences. In the legal sphere, the Germanic tribes took their cue from Roman law, just as they endeavored in general to adapt themselves to the Roman way of life. Some Germanic rulers, who perhaps drew their authority primarily from an army kingship, adopted the Roman imperial name Flavius (such as Theoderic the Great) and often drew on the Roman elites for administrative tasks, with the church in particular playing an important role as a unifying force. Often "Germanic" did not represent an antithesis to "Roman," especially since the Germanic peoples constituted only a fraction of the population in the regna. In many respects, the new monarchies drew on Roman imperial rather than Germanic traditions - all the more so because today it is increasingly doubted that there had been any pre-Roman Germanic kingship at all. On the other hand, there were educated individuals who came to terms with the new masters in the West, as the examples of Bishop Avitus of Vienne, the physician Anthimus, or the poet Venantius Fortunatus, among others, show.

For modern research, which in recent decades has paid increased attention to the period between the 4th and 8th centuries, more and more new questions arise, for example with regard to the problem of continuity (see also the remarks in Pirenne-These). The change of rule was sometimes fluid: in the Frankish Empire, for example, people were now no longer subordinates of the emperor but of the king (even if Augustus in Constantinople was still often addressed there as dominus noster in the late 6th century). Roman officialdom was partially adopted, as were administrative structures. For a time, the late Roman institutions also continued to function, until finally no sufficiently trained personnel followed. The members of the old provincial Roman elite now often preferred to choose an ecclesiastical career. On the other hand, comites continued to exist, which administered the civitates until the comes finally became the "count". In Gaul, the Franks also stood up to Alamannic plunderers and defended the cities: Gallia finally became Francia. After a while, new offices arose at the Germanic rulers' courts, such as maior domus (house-meier) in the Merovingian Empire. The tendency towards the consolidation of aristocratic structures, which had already progressed in late Roman times, became increasingly clear, as reflected, for example, in the contrast between the large landowners and the peasants bound to the sheol. Society soon divided into freemen (which included the Germanic nobles and the Roman upper class), semi-freemen and unfree. This was accompanied by an increase in the number of slaves, but several detailed issues are disputed. For example, the development in the individual regna was quite different. Above all, many assessments of older research, which characterized late Roman society as generally in decline, have been revised by modern scholarship. Nevertheless, the population in the cities of the West, for example, declined overall. In some regions, for example in Britain and in parts of the Danube region, the urban culture typical of antiquity even disappeared almost completely. In the artistic field, however, new forms dominated (see fibula, Germanic animal style). In addition, among other things, the burial culture changed. Thus, Romans were also buried in the Germanic, i.e. "barbarian", manner.

In general, there are different approaches to explaining and assessing the changes in the Mediterranean world in the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. To this end, the European Science Foundation has even launched its own research project, Transformation of the Roman World. One thing, however, is becoming increasingly clear: the Germanic regna were no less a part of the late Roman world than the empire itself.

The Mediterranean at the time of Emperor Justinian I († 565)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the migration period?

A: The migration period, also known as the barbarian invasions or Völkerwanderung, refers to a period of migration that took place in Europe between AD 300 and 700.

Q: Who were some of the tribes that migrated during this period?

A: The migrations included the Goths, Vandals, Franks, and other Germanic, Bulgar, and Slavic tribes.

Q: What factors may have influenced these migrations?

A: The migrations may have been influenced by attacks of the Huns in the East, Turkic migrations in Central Asia, overpopulation, or climate changes.

Q: Which groups migrated to Britain during this period?

A: Groups that migrated to Britain during this period include the Angles, Saxons, Frisians, and some Jutes.

Q: Did migrations continue beyond AD 1000?

A: Yes, migrations continued well beyond AD 1000 with successive waves of Slavs, Roma, Avars, Bulgars, Hungarians, Pechenegs, Cumans, and Tatars that changed the ethnic makeup of Eastern Europe.

Q: What migrations do Western European historians tend to focus on?

A: Western European historians tend to focus on the migrations that were most relevant to Western Europe.

Q: When did the migration period take place?

A: The migration period took place between AD 300 and 700.

Search within the encyclopedia