Mexican Revolution

This is the sighted version that was marked on April 25, 2021. There is 1 pending change that needs to be sighted.

The Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Revolución mexicana) or Mexican Civil War (Spanish: Guerra civil mexicana) is the term used to describe the political and social upheaval that began in 1910, when opposition groups led by Francisco Madero began to overthrow the dictatorial Mexican president Porfirio Díaz. The uprising against Díaz was the beginning of a series of sometimes exceedingly bloody struggles and unrest that engulfed large parts of Mexico and kept the country unsettled well into the 1920s. In the process, not only were the conflicting interests of the very different political-social supporting groups of the Mexican Revolution fought out, but in some cases a genuine social revolution was realized. The main force behind the social revolutionary side of the revolution was the Zapatista movement, which in turn was based on the ideas of the anarchist Magonistas, who propagated indigenous collectivism and libertarian socialism under the slogan Tierra y Libertad ("Land and Freedom").

The main results of the protracted struggles of the Mexican Revolution, which were completed by about 1920, were the violent political ousting of the old Mexican oligarchy and the destruction or transformation of the Porfirist state apparatus and the pre-revolutionary army. This was accompanied by the rise of a new ruling class from the ranks of the various revolutionary movements and the emergence of new state structures. In many cases, however, these could only be implemented in the face of resistance from local autonomy movements, which had become politically powerful at a time when the country lacked a strong central authority. Accordingly, revolts by individual army commanders and uprisings by certain ethnic groups or segments of the population against the new central government continued to occur until the early 1930s. The implementation of significant social reforms, which had been one of the main reasons for the outbreak of the revolution in 1910, therefore only took place with considerable delay under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río.

Major battles, military campaigns, and uprisings of the Mexican Revolution.

1st phase: Fall of the Díaz regime (1910-1911)

Ciudad Guerrero - Casas Grandes - Agua Prieta I - Ciudad Juárez I - Torreón I - Cuautla I

2nd phase: Maderos presidency (1911-1913)

Vázquista revolt - Orozco revolt - Morelos campaign I - Decena Trágica

3rd phase: Revolt against the regime of Huerta and intervention of the USA (1913-1914)

San Andrés - Torreón II - Sinaloa - Ciudad Chihuahua I - Culiacán - Ciudad Juárez II - Tierra Blanca - Ojinaga - Cuautla II - Torreón III - Acaponeta - Tepic - Paredón - San Pedro - Veracruz - Tampico - Zacatecas - Orendaín

4th phase: Civil war between conventionists and constitutionalists (1914-1915)

Naco - Ramos Arizpe - Guadalajara - Blanca Flor - Halacho - Matamoros - El Ébano - Celaya - León-Trinidad - Aguascalientes - Agua Prieta II - Hermosillo

5th phase: Carranza's rule and renewed intervention of the USA (1916-1920)

Columbus - Morelos Campaign II - Mexican Expedition - Ciudad Chihuahua II - Ciudad Chihuahua III - Horcasitas - Zapatas Offensive - Torreón IV - Estación Reforma - Rosario - González' Offensive - Ciudad Juárez III

6th phase: Restoration of the central power and rule of the Sonorenses (1920-1934)

Baja-California campaign - De-la-Huerta revolt - Cristero revolt - Yaqui war - Gómez-Serrano revolt - Escobar rebellion

Initial situation: Mexico under Porfirio Díaz

Political situation

After decades of constantly changing governments, civil wars and military interventions by foreign powers, Mexico experienced an unprecedented period of domestic stability and peace in the 19th century during the long-lasting second presidency of Porfirio Díaz. This was due in no small part to Díaz's centralization of political power in Mexico, which led not only to state penetration of previously peripheral areas - in administrative terms - but also to the establishment of a strong national executive. This enabled the government to exercise political control down to the local level and to enforce orders much more effectively than before. Regional spheres of power, the cacicazgos, were successively eliminated or, if that was not possible, their holders at least committed to permanent loyalty to the central government. Insofar as the state governors, who had previously often acted largely independently, but also other regional and local potentates of all kinds, were willing to tolerate state intervention in their former domains of power, they were offered the opportunity in return to enrich themselves and their family members, for example by granting concessions and state sinecures of all kinds or by ceding state land at preferential prices.

The Díaz regime's concentration of political power and its policy of pan o palo ("carrot or stick"), which had initially been quite beneficial for the country as a whole, became increasingly problematic in the long run, however. Not only did an unprecedented system of patronage emerge, with all its negative concomitants such as bribery and corruption, but there was also a widespread loss of importance of the legislative and judicial branches vis-à-vis the executive, the erosion of many traditional rights of the states, and a successive restriction of the autonomy of the municipalities. The entire system of rule began to be increasingly centered on the person of the president, whose style of government took on increasingly autocratic characteristics. After Díaz began his third term in 1888, no governor or deputy could de facto be elected to the federal congress unless he had first received the president's approval. The result was an increasing oligarchization of the state and society and - associated with this - a perpetuation of positions of power whose holders were soon recruited only from a small and closed circle of cliques and families absolutely loyal to the president. Towards the end of Díaz's term in office, there was not only an "aging of most of the [political] leading figures", but also an almost total "petrification of the Mexican political system". The emergence of a nationally organized opposition movement that could have formed a political counterweight to the president and his henchmen was very difficult in Mexico due to the patrimonialist character of the governmental system, the lack of genuine political parties and free and fair elections, and the intimidation and repression measures of the police apparatus, which worked efficiently in the interests of the regime.

Economic situation

Parallel to the political centralization of Mexico, the economic modernization of the country was also systematically advanced under President Díaz in the 19th century. The expansion of the infrastructure, especially the railway network and the raw materials producing and processing industries, and the commercialization of agriculture were specifically promoted. After 1900, moreover, Mexico's rich petroleum resources began to become an increasing focus of economic interest, and by 1913 Mexico was the third largest petroleum producer in the world. This had the effect of transforming Mexico's economy from one that had previously been locally and regionally structured to one that was export-oriented, increasingly integrated into the U.S. economy and permeated by U.S. capital from the late 19th century onward. By 1910, 56 percent of Mexican imports came from the United States and 80 percent of Mexican exports went there. The United States had already been the largest investor in Mexico by the end of the 19th century. American firms and individual entrepreneurs owned vast tracts of land in Mexico, were shareholders or owners of numerous Mexican banks, mines, and other enterprises of all kinds, but especially the oil companies.

As impressive as Mexico's economic boom was in itself, the wealth was unequally distributed. The vast majority of the Mexican population did not benefit in any way from the tremendous economic growth. In 1910, for example, about one percent of the population owned and controlled 96 percent of the land. Ninety percent of the rural population did not own land, so they had to hire themselves out as laborers. In doing so, they easily fell into debt bondage, which could hardly be distinguished from real slavery. These conditions were literarily processed in the Caoba cycle by B. Traven. In addition, between 1876 and 1912 community pastures in the order of about 1340 km² were lost.

Hot spots in late porfirist Mexico

The above-mentioned political and economic conditions resulted in a series of specific crisis phenomena that "can be understood as the structural preconditions [...] of the revolution", but which were also responsible for its very different course in the individual parts of the country. Significant for the outbreak of the revolution, for example, was the fact that the consensus of the middle and upper classes with the Díaz regime, which had been essential for its political stability, was increasingly called into question in the last five years of Díaz's rule. The political and economic monopoly that Díaz's minions had achieved in many parts of the country-for example, the Terrazas-Creel family clan in Chihuahua-not only marginalized the middle classes, but alienated even sections of the upper class from the regime. In addition, the tax and credit policies adopted by the Mexican government in the wake of the North American economic crisis of 1907 were particularly detrimental to the middle classes. There was great discontent, for example, among the numerous state employees, but also among small merchants and members of the liberal professions, most of whom saw no possibility of social advancement and whose standard of living was threatened when real wages fell toward the end of Díaz's reign. The first leaders of the revolution in northern Mexico, for example, were to be recruited from the political opposition movement that was gradually emerging in these circles.

The development of Mexico's agricultural sector also represented a particular kind of flashpoint. In this context, however, it should be emphasized that the conflict often postulated in the past between the rich hacienderos, who had vast estates at their disposal, and the oppressed peones, who were completely landless and destitute, does not adequately represent Mexico's social realities during this period. Agrarian development during Díaz's presidency was much more complicated and was also marked, above all, by the emergence of a relatively wealthy peasant middle class, the rancheros. That developments in the agrarian sector were nevertheless to become one of the causes of the revolution was due to their economic, but even more so to their political-social effects. Indeed, commercial and technical innovations in Mexican agriculture led to increased economic pressure and the economic displacement of many small tenants and farmers as well as previously independent agricultural producers. Although this development varied greatly from region to region, research has found that by the end of Díaz's reign, a significant portion of the rural population had fallen into economic distress.

The conflict between large landowners and small farmers in the states of Morelos and the northern part of Chihuahua was particularly conflictual. In Morelos, where sugar had been grown since colonial times, the modernisation of sugar production had also made it necessary to expand the area under cultivation. In the densely populated state, however, this was only possible at the expense of the landowning villages, the pueblos, and the still independent small and medium-sized owners, and increasingly took the form of a systematic expropriation policy on the part of the large landowners. Their pseudo-legal, but often purely extortionate actions were mostly crowned with success due to the silence of the local authorities and the corrupt courts. The constant expansion of the haciendaland gradually deprived the pueblos of their economic basis and led to a decline of the latter by about one sixth between 1876 and 1910. The peasants thus deprived of land often had no other option than to work on the hacienda that had taken their land. The resulting dependency led to a proletarianization of the rural population in Morelos. Although many villages had lost their land or parts of it, they continued to exist as politically independent units. In this way, those affected by the land theft not only had a forum for protest and political expression, but also found social support in the still intact village community. This in turn favoured the emergence of organised resistance to the land expropriations, which also explains why the revolution found numerous supporters from the outset, particularly in Morelos.

In the northern part of Chihuahua, the land theft by the large landowners mainly affected those farmers and cattle ranchers who were descendants of the military colonists settled in the 19th century to ward off Indian incursions (mainly Apaches and Comanches). After the Apaches were finally defeated in the 1880s, the services of the former colonists were no longer needed and they were gradually deprived of the special rights they had been generously granted. Subsequently they were deprived of their land on a large scale. Like their comrades in Morelos, they were therefore among the revolutionaries of the first hour.

Finally, the Yaqui Indians in Sonora formed a special group of revolutionaries. During Díaz's reign, they had been in an almost permanent state of war with the Mexican government, which was especially intent on the land they collectively farmed and held sacred. The Yaqui wars were surpassed in cruelty only by the so-called caste wars against the Maya population of Yucatán. On the eve of the revolution, the Yaquis were still not completely defeated, but many of them had by then been killed or deported as forced laborers to the plantations of Yucatán. If the Yaquis still living in freedom were not already waging a permanent guerrilla war against all whites, they joined Francisco Madero at the beginning of the revolution, at least nominally, but they soon fought him again because he did not give them back their land either. Only Alvaro Obregon succeeded in integrating a larger part of the Yaquis into his army and thus integrating them more firmly into the revolutionary camp.

Mexico's long-term president Porfirio Díaz

Mexico City around the time of the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution

Course of the Mexican Revolution

Overthrow of the Díaz regime (1910/11)

In 1908, Mexico's aged president had attracted attention with an interview he had given to the US journalist James Creelman. In it he had held out the option of his resignation at the end of the current term of office with the simultaneous democratic election of a successor and even encouraged the formation of opposition parties. Subsequently, an independent political movement formed around the popular general and governor of the state of Nuevo León, Bernardo Reyes, who was considered the most promising successor candidate. However, the president's veto in favour of the candidate from his inner circle of power and the relegation of Reyes to a post abroad broke the back of the new electoral movement and allowed Francisco Madero, a hitherto largely unknown scion of a wealthy landowning family from the state of Coahuila, to come to the fore. In his paper "La sucesión presidencial en 1910", published at the end of 1908, Madero had argued for a democratic political system in Mexico and caused a sensation. With the nomination of Madero and the physician Francisco Vázquez Gómez as presidential and vice-presidential candidates, Díaz's position of power was openly challenged for the first time. Under the slogans "Sufragio efectivo - No Reeleccion" ("Actual Suffrage - No Reelection"), Madero's anti-reelectionist party developed into a popular movement that was increasingly perceived as a threat by the ruling regime. Eventually, Díaz abandoned his initial tolerance, had Madero and his closest comrades-in-arms arrested, and his movement crushed. After a staged re-election, Díaz's victory and that of his vice-president Ramón Corral were declared. Madero, after escaping from San Luis Potosí prison to the United States, now called on Mexicans to overthrow the president on November 20, 1910, in the "Plan of San Luis Potosí."

Contrary to Madero's expectations, his call was echoed above all in the rural regions, where numerous armed groups, including those of Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa in the northern state of Chihuahua, began fighting Díaz. In March 1911, another front against Díaz was opened in the state of Morelos, south of the capital, by Emiliano Zapata. In the large cities, however, the Porfirist army and police were usually able to nip Maderist attempts at insurrection in the bud and maintain control for some time. In the long run, however, the poorly led, inadequately equipped and understaffed federal army, whose command structures were entirely tailored to the person of the president, proved too weak to cope with the insurgencies that were flaring up in more and more places. The obvious military weakness of the regime encouraged further uprisings and at the same time caused increasing paralysis in the political-administrative apparatus. When in May 1911 the united northern rebel contingents succeeded in capturing the border town of Ciudad Juárez, thus acquiring an important base for the supply of arms and ammunition from the United States, Díaz finally gave in to the urging of his closest collaborators, declared his resignation on May 17, and went into exile in Paris. In accordance with the constitution, the former Foreign Minister Francisco León de la Barra now assumed the function of interim president, to whom the preparation of new elections also fell. On May 21, 1911, the hostilities were officially declared over with the "Treaty of Ciudad Juárez" (Tratado de Ciudad Juárez), whose most important component was the restoration of public order and the release of the various rebel contingents as quickly as possible. With this treaty, in which Madero made far-reaching concessions to the remaining exponents of the old system and which by no means met with the undivided approval of his supporters, the first phase of the Mexican Revolution had reached its conclusion.

Presidency Maderos (1911-1913)

In October 1911 Madero was elected as the new president. He disappointed the hopes placed in him after only a short time, however, because he not only clung to the old structures in the army and administration, but in many cases also left the old officials in their positions. His nepotism, but above all the lack of a land reform, did the rest and increasingly turned larger parts of the population against him. The first to revolt against Madero were the Zapatistas. In the "Plan of Ayala" of November 25, 1911, they not only denied him his authority as leader of the revolution and as president of Mexico, but also founded their own revolution, the "Revolution of the South" (Revolución del Sur). The centerpiece of Ayala's plan, however, was the restitution of the land expropriated by the hacendados to its old and rightful owners, the pueblos, that is, the villages or village communities. Although Madero was not fundamentally opposed to the Zapatistas' list of demands, as ultimately expressed in Ayala's plan as a basic document, in order to preserve the authority of his new office he had first demanded their unconditional surrender. In the conflict that now followed, the people of Morelos experienced a particularly brutal pacification campaign by the federal army, whose commander, General Juvencio Robles, burned entire villages and forcibly conscripted all able-bodied men into the army. However, he failed in his goal of quelling the insurgency and instead caused the hard-pressed population to solidarize with Zapata's troops. Ultimately, the conflict with the Zapatistas remained an unresolved problem for Madero, albeit one confined to the state of Morelos. This was also due to the fact that the Zapatistas pursued an agenda very much limited to their local and regional agrarian clientele, which was hardly attractive to segments of the population whose source of income was not agriculture and who lived outside Morelos.

In contrast to that of the Zapatistas, the uprising of the popular former revolutionary general and Madero supporter Pascual Orozco, which broke out in March 1912 and was also joined by other revolutionary leaders who had formerly fought for Madero, carried the danger of expanding into a conflagration. Despite social demands, such as those also made by Orozco and his military leaders, in reality their disappointed hopes for important political positions after the fall of Diaz were a major driving force behind this revolt. With the help of the federal army under Victoriano Huerta, Orozco's uprising was put down relatively quickly. However, this did not change the fact that Madero had not only successively deprived himself of his own power base, but had also proven himself incapable of controlling the situation and calming the country in the eyes of the old Porfirist elites, who still sat in numerous positions of power. Part of the reason for Madero's political mistakes and his reluctance to quickly tackle pressing problems such as land reform was that he was under the illusion that Mexico's social conflicts would lose their political-social explosive force almost by themselves in a democratic system. The creation of a democratic order while at the same time preserving "a continuity of the legal order" was the top priority for the leading Maderists; in contrast, the redistribution of land and other resources was of only secondary importance to them.

Ultimately, Madero's political survival depended on the army, which he had generously chosen to be the guardian of the new revolutionary order. In fact, however, many members of the old Porfirist officer corps could not come to terms with the new circumstances. Although they had actively participated in the suppression of the revolts from the ranks of Madero's ex-party supporters, they otherwise behaved indifferently at best toward the new government. Two military rebellions, that of Bernardo Reyes, who had returned from North American exile, and that of Felix Díaz, a nephew of the ousted long-term dictator, had failed miserably, but should have been a warning signal to the government. The two insurgents, who had escaped execution and had numerous sympathizers in the army, continued to conspire against the government from prison. Finally, in February 1913, there was a coup against the government, in the course of which Madero was deprived of his power and shortly afterward assassinated with some of his closest partisans. Involved in this coup d'état, from which the commander-in-chief of the army, Victoriano Huerta, was to emerge as the new ruler, was also the US ambassador Henry Lane Wilson (1857-1932), who had assured Huerta and his comrades-in-arms that their project could count on the goodwill of the US government. Huerta's coup d'état went down in Mexican history as Decena Trágica, the "ten tragic days", because army units loyal to the government fought with insurgent army units in the capital for ten days, which also claimed numerous victims among the civilian population.

The Huertas regime (1913-1914)

Huerta had initially succeeded in carrying out the transfer of power relatively smoothly. He was greatly helped in this by the fact that, with the exception of a few states in northern Mexico, there had been no personnel changes in either the army leadership or the senior civil service during Madero's presidency, and the social structure of the country had hardly changed either. Huerta, as the new ruler, was therefore able to rely on still powerful and influential political-social groups and networks of the former Porfirist regime, "which gave his rule an unmistakably restorative character. " The majority of the individual states also came to terms with the new ruler, but this was not the case with two states: Sonora and Coahuila. The governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, had the coup of Huerta condemned by the legislature of "his" state and deprived the usurper of the right to the presidency in the "Plan of Guadalupe" of March 26, 1913. At the same time, in this manifesto to the nation, he proclaimed himself primer jefe, supreme leader of the "constitutionalist" armed forces, that is, those loyal to the Constitution. He derived his claim to leadership from the fact that, as the elected head of a state within the anti-Huerta opposition, he was virtually the highest representative of the constitutional order. Although Carranza soon had to give way to the military superiority of Huerta's federal army in Coahuila, he nevertheless succeeded in consolidating his authority as the supreme head of the anti-Huerta movement in the following months.

In addition to the quasi-state resistance organized by the two northern states, spontaneous resistance groups soon formed in northern Mexico, including Pancho Villa's, which was soon to become one of the most important; and after negotiations with the Zapatistas on a ceasefire failed, Huerta found himself forced to take military action on this front as well. In addition, in the months following his assumption of power, opposition to Huerta's regime grew within the Congress elected under Madero. In October 1913, Huerta had the congress dissolved by force and manipulated new elections, with the result that his style of government took on increasingly unmistakable dictatorial features. Huerta's relations with the United States, which began to deteriorate rapidly soon after he came to power, also became an ongoing problem. Although U.S. Ambassador Wilson had attempted to obtain recognition of Huerta's regime by his country after the coup, he had been unsuccessful. The expiring administration of President William Howard Taft was no longer prepared to take such a step. For Taft's successor Woodrow Wilson, who detested the way Huerta had taken power, recognition of his regime under international law was out of the question. Exacerbating the conflict was the fact that, like Madero before him, Huerta was not prepared to fulfil the hopes of the United States for special promotion of its primarily economic interests in Mexico. Huerta wanted to retain some room for maneuver in foreign policy and therefore promoted British firms and corporations as a counterweight to U.S. ones. After their attempts to persuade Huerta to resign through economic and diplomatic pressure failed, the U.S. administration took the violent dissolution of the Mexican Congress as an opportunity to shift to a policy of open support for Huerta's opponents. In early February 1914, the arms embargo on Mexico was relaxed, which meant that rebel forces operating in the northern Mexican states could now obtain quasi-legal supplies of arms, ammunition, and all other supplies from the United States. Finally, the United States took an incident that was in and of itself trivial and occupied the port city of Veracruz in April 1914. In doing so, they deprived Huerta not only of important customs revenues but also of its most important port of entry for European arms. After the occupation of Veracruz, the ABC states (Argentina, Brazil, and Chile) launched an offer of mediation to resolve U.S.-Mexican differences. However, the initial hopes of the U.S. to secure a determining influence in the readjustment of Mexican relations in these negotiations to be conducted at Niagara Falls were not fulfilled. The constitutionalists showed no interest in such talks; rather, they were determined to seek a military decision in the Mexican civil war and in this way eliminate the remnants of the old Porfirist state apparatus once and for all.

This change of attitude on the part of the Constitutionalists led to a Civil War fought with unprecedented acrimony and with the participation of broad masses of the people, with relatively large and well-equipped forces on both sides. The Constitutionalist forces in the northern states, which were easily supplied with weapons because of the attitude of the United States, transformed already in the course of 1913 from initially loosely organized and small formations that had fought Huerta's federal army with hit-and-run tactics, often with the tacit support of the population, into compact and combat-strong armies. These could henceforth engage their opponents in open field battles and usually remained victorious. Another characteristic of these constitutionalist combat units was that they had sophisticated logistics at their disposal - by Mexican standards - and usually reached their military bases, which were often far apart, by rail. Only the Zapatistas in the south, who had no economic basis comparable to the northern revolutionary troops and, due to the isolated location of their battlefield, also had no possibility of supplying themselves with weapons and ammunition from abroad, were never able to completely dispense with guerrilla warfare. Accordingly, they also did not require extensive logistical effort, firstly because their combat area was much smaller, secondly because they could count on the support of the local population, and thirdly because they were predominantly peasant soldiers who supplied themselves wherever possible and returned to their farms after the end of a combat action, raid or campaign.

In the north of Mexico, it was three revolutionary armies in particular that soon made a name for themselves: From Sonora, the "Army of the Northwest" (Ejército del Noreste), commanded by Alvaro Obregón, advanced south along the Pacific coast toward Mexico City. The "Division of the North" (División del Norte), commanded by Pancho Villa and formed in the fall of 1913 from various rebel groups in the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila and Durango, operated in the center and had passed its baptism of fire with the conquest of the city of Torreón. It drove the federal army completely out of the state of Chihuahua by the beginning of 1914 and then also set out on the long road toward Mexico City. The "Army of the Northeast" (Ejército del Noreste), commanded by Pablo González, gradually wrested control of Mexico's northeastern states from Huerta's forces. In addition, there were anti-Huerta movements in quite a few other parts of the country, most of which, however, did not attain supraregional significance and in the course of further events joined at least nominally the armed forces of Obregón, Villa or Zapata.

Huerta met the growing military challenges with a massive increase in the federal army. However, quantity was greatly at the expense of quality, since his government could only achieve this plan through the rigorous use of forced recruitment; and even this "only" increased the effective level of the armed forces to about 125,000 of the planned 250,000 men. The consequences of these forced recruitments were consistently poor fighting morale and a high desertion rate among the federales, the members of the federal army, as well as an increasing turning away of the population from Huerta's regime. The latter's position of power had been increasingly shaken since the fall of 1913 by mounting setbacks in the struggle against the forces of the constitutionalists, and finally collapsed after the crushing defeats of his armies at Zacatecas and at Orendaín. In June 1914 Villa's force had taken by storm the important garrison town of Zacatecas, which was Huerta's last bulwark along the railroad from Chihuahua to Mexico City; and in July 1914, only two weeks later, Obregón, in a no less bloody battle, annihilated Huerta's army holding Guadalajara and forced his way into the capital from that side. Faced with these now irreplaceable losses, Huerta finally surrendered and embarked for Europe on the Ypiranga on July 15, 1914.

Huerta's constitutional successor as president was the former foreign minister Francisco S. Carvajal. Immediately before the end of his short term in office, the "Treaty of Teoloyucán" was signed on August 12, 1914, with which the Mexican federal army surrendered unconditionally to Obregón's victorious forces. This also put an end to the hostilities between "constitutionalists" and Huertistas. This treaty secured Obregón's army access to Mexico City and contained as a further provision that the units of the federal army stationed south of the capital against the Zapatistas would not have to leave their positions until they had been replaced by units of Obregón's army. Villa had already been prevented from advancing further by rail after his victory. In this way, the revolutionary leaders, who had long been viewed with suspicion by Carranza, were denied access to Mexico City.

Renewed civil war and Carranza's government (1915-1920)

The anti-Huerta coalition, in which the first cracks had already become visible during the war against Huerta, quickly broke apart again after the latter's fall. The divergent ideas of Zapata, Villa and Carranza, who after the victory over Huerta continued to insist on his claim to leadership in Mexico as the "supreme chief of the constitutionalist army, endowed with the executive power of the nation", could not be reconciled. After Villa had refused to attend the convention of governors and generals in Mexico City called by Carranza for early October 1914, and negotiations for the Zapatistas' entry into Carranza's camp had also failed, a clash of arms between Villa and Zapata on the one side and Carranza on the other was predictable. To Carranza's surprise, the Convention he had called was unwilling to grant him alone the "executive power" he demanded, and adjourned to resume its sessions in Aguascalientes. There the Convention turned fully against Carranza, confirmed Villa in his position as commander of the revolutionary army he commanded, and elected General Eulalio Gutiérrez as provisional president. Carranza, for his part, now declared the Convention's arrangements invalid and announced that he would continue to serve as Mexico's supreme executive.

In the civil war that now began between "conventionists" and "constitutionalists," Carranza initially turned against Villa, the strongest of his opponents. With the help of Alvaro Obregón, a rancher who had acquired his considerable military skills autodidactically, Carranza succeeded in driving Villa's army further and further north until the end of 1915 in a series of bloody battles, the decisive ones of which were those at Celaya, León-Trinidad and Aguascalientes, and eliminating it as a supraregional power factor. When, with the battles at Agua Prieta and Hermosillo, Villa's attempt to refresh his battered forces by an advance into the state of Sonora had also failed, he finally sank back to the status of guerrilla leader. Many of his men accepted Carranza's offer of amnesty and either left the civil war for good or joined the ranks of their erstwhile military opponents. With the remaining troops - probably no more than 1000 men at the end of 1915/beginning of 1916 - Villa continued to wage a tenacious guerrilla war against Carranza.

After the United States' recognition of the Carranza government in October 1915, Villa also began to cause increasing foreign policy problems for the United States by targeting and murdering U.S. citizens. The Villistas' raid on the U.S. border town of Columbus in March 1916 resulted in renewed U.S. military intervention in Mexico, this time to capture Villa. The so-called "punitive expedition" into Mexico brought the Carranza government to the brink of war with the U.S. and caused Villa's popularity to soar again, temporarily reestablishing his position of power in northern Mexico. However, after the U.S. left Mexico in February 1917 due to imminent intervention in World War I, Villa's newfound power position quickly collapsed. That same month, Mexico had also received a new constitution that addressed numerous demands of the revolutionaries. However, the implementation of the corresponding constitutional articles was delayed by the socially conservative Carranza regime, which ultimately contributed significantly to its inability to gain support among either the working class or the rural population.

By this time, even the Zapatistas in the south no longer posed a real threat to the Carranza regime, because in 1916 and 1917 they had increasingly fallen on the military defensive and were soon fighting only for their own survival. This military success of the Carranza regime, however, could not hide the fact that the political dimension of the "Zapata problem" remained, especially since Zapata showed clear sympathy for the latter in the confrontation between Carranza and Obregón that had been emerging since mid-1917. With the assassination of Zapata by the Carranza regime in April 1919, the revolution entered a new phase: that of the open power struggle between Obregón and Carranza, the starting point of which were the presidential elections scheduled for 1920. In this power struggle, Obregón was able to win over not only the remaining Zapatistas, but also the majority of the army commanders, whose loyalty Carranza could never be sure of. By May 1920, the power struggle had already been decided with the assassination of Carranza after his escape from Mexico City. Towards the end of the year Obregón was elected president, which in view of his unchallenged position of power was little more than a formality.

Presidency of Obregón (1920-1924)

In contrast to his predecessor, Álvaro Obregón actually succeeded in largely stabilizing the country domestically and externally during his term in office (1920-1924). Even Villa was persuaded to finally cease his fight against the government. However, even Obregón was unable to achieve effective political control of the army leadership, and, as in 1920, the question of who should succeed him in the presidential elections scheduled for 1924 led to an open rebellion by numerous senior army leaders and the troops under their command at the end of 1923. Against Plutarco Elías Calles, favored by Obregón as future president and suspected of involvement in the assassination of Pancho Villa in July 1923 under dubious circumstances, the insurgent army leaders sought to impose the interim president of 1920, Adolfo de la Huerta. The renewed fighting, which, like the power struggle between Carranza and Obregón, was essentially confined to the rival army factions, was won by the Obregón regime by May 1924. After bloody purges in the ranks of the insurgent army leaders, the election of Calles as president in July 1924 passed without further incident.

Presidency Calles (1924-1928) and Maximat (until 1935)

Political consolidation enabled the new president to devote himself more than any of his predecessors to the economic reconstruction of Mexico, with priority given to the expansion of infrastructure and education after the deficit-ridden state budget had been reorganized and a modern tax system introduced. However, the implementation of the anti-clerical provisions of the 1917 constitution and the founding of a Mexican state church independent of the Vatican in February 1925 gave rise to a new source of conflict that finally expanded into a widespread insurrectionary movement against the Calles regime in 1926. This so-called Cristiada mainly affected the central and western highlands of Mexico, where Catholicism was particularly strongly rooted in large parts of the mostly peasant population. The uprising of the Cristeros, in which extreme brutality was used on both sides, could only be put down in 1929 by the new federal army, which had emerged from the former revolutionary troops.

Domestically, Calles' position of power was already uncontested at this time. He had cleverly used the assassination of Obregón by a fanatical Catholic in July 1928 to secure for himself a dominant political role in Mexico even after the end of his term as president, which he maintained as jefe máximo under various presidents who were de facto only his stooges until 1935. The reforms instituted by Calles during his presidency and subsequent maximat, as well as the complete normalization of relations with the United States, finally enabled his successor, Lázaro Cárdenas, who sent Calles into exile in the United States in the spring of 1936, to carry out those sweeping social and economic measures with which the Mexican Revolution is considered finally concluded.

Soldiers of the US "punitive expedition" on the march (photo from 1916) .

Photo of the National Palace in Mexico City, taken during the fighting of the Decena trágica in 1913.

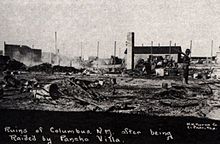

Columbus after the raid of the Villistas in March 1916

Francisco Madero, his wife and rebels (photo from the first half of 1911)

Search within the encyclopedia