Marxism

Marxism is the name of a social doctrine founded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 19th century. Its goal is to create a classless society through revolutionary transformation in place of the existing class society.

Marxism is an influential political, scientific and ideological movement that is classified as both socialism and communism. Since the second half of the 19th century, the followers of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels have been referred to as Marxists. In a broader sense, Marxism is a collective term for the economic and social theory developed by Marx and Engels, as well as for related philosophical and political views. Individuals and schools of thought that connect in specific ways to the work of Marx and Engels are also included in Marxism.

Well-known Marxist currents include the Orthodox Marxism of early social democracy (essentially late 19th/early 20th century), Leninism, Marxism-Leninism, Maoism, Trotskyism, and various forms of Western or Neo-Marxism, including the Frankfurt School and French Structuralist Marxism, Italian Operaism, Yugoslav Titoism, and Post-Marxism.

Marxism has its theoretical roots, among other things, in the critical examination of classical German philosophy (Kant, Hegel, Feuerbach), classical English national economics (Smith, Ricardo), early French socialism (Fourier, Saint-Simon, Blanqui, Proudhon) and the historians of the French Restoration (Thierry, Guizot, Mignet). Above all Engels, Karl Kautsky and Lenin, but also Plekhanov, Labriola, Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg had a lasting influence on the further development of Marxism. In a second phase after the First World War up to the '68 movements, Marxism underwent further differentiation through Karl Korsch, Georg Lukács, Antonio Gramsci, Ernest Mandel, André Gorz, Herbert Marcuse, Theodor W. Adorno and Louis Althusser.

Over time, an independent Marxist philosophy developed, and in many disciplines of the sciences with a social connection, separate Marxist currents developed - such as a Marxist sociology, a Marxist economic theory, a Marxist literary theory, or in psychoanalysis, Freudo-Marxism.

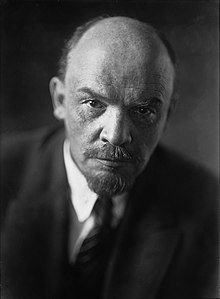

Lenin (1870-1924)

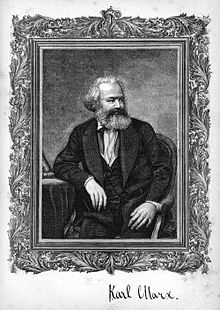

Karl Marx (1818-1883), steel engraving from Le Capital, Paris 1872

Karl Kautsky (1854-1938)

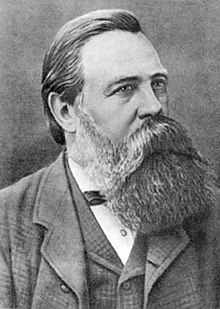

Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), photo: W. Hall, Brighton 1877

Theory

Philosophy

→ Main article: Marxist philosophy

Although Marx and Engels primarily pursued a critique of philosophy and ideology, which aimed at the emancipation of man, Marxism itself is sometimes understood as a philosophical doctrine with a humanistic character. In terms of epistemology and scientific theory, Marxism is characterized by two essential elements: Hegel's dialectics and Feuerbach's epistemological materialism. Lenin refers to materialism as the philosophy of Marxism. Marx already criticized the philosophers in 1845 in his famous sentence:

"Philosophers have only interpreted the world differently; what matters is to change it."

In contrast to philosophical idealism, Marxism holds the view that all ideas, conceptions and thoughts arise from the complex, especially social reality and the power relations that contain them, which would develop "in the last instance" from the respective historical-geographical relations of production and material conditions. Marx and Engels - influenced by the Young Hegelians - adopted Feuerbach's materialist world view and supplemented the dialectic and the associated idea of constant development from the work of Hegel.

Marx and Engels thus overcame what they saw as the one-sided view of the mechanical materialists, who saw the world as unchanging. In 1843, Karl Marx adopted Hegel's figure of thought of dialectics as well as the assumption of a regularity of history. Unlike Hegel, however, he did not attribute this to the unfolding of the "world spirit", but to material, social conditions and conflicts within society.

Lenin refers to the philosophical views of Marx and Engels as dialectical materialism, although they did not use this term themselves. Lenin refers to the materialist dialectics of Marx and Engels as

"the doctrine of the relativity of human knowledge, which gives us a reflection of eternally evolving matter."

In the discovery of the radium, the electron as well as the transformation of the elements, Lenin sees a confirmation of these views, which would refute the idealist postulate of eternal standstill. According to Hegelian dialectics, the image of the world in the active comprehension of its interrelationships is characterized by interrelated opposites - theses and antitheses - which mutually advance in the dialectical three-step to syntheses. These syntheses drive "objective reality" forward and thus "determine" the future until it no longer contains contradictions and is "suspended" in the concept of the "absolute". For the idealist philosopher, this progress, which permeates the material world as a whole, is a product of the human spirit, which in grasping itself becomes identical with the absolute "world spirit".

Marx looks at the Hegelian dialectic from the point of view of materialism: he turns it "upside down" and postulates that objective reality can be explained by its material existence and its development, and not as the realization of a divine absolute idea or as the product of human thought.

"My dialectical method is not only different from Hegel's in its basis, but its direct antithesis. For Hegel, the thought-process, which he even transforms into an independent subject under the name Idea, is the demiurge of the real, which only forms its outer appearance. With me, conversely, the ideal is nothing but the material transposed and translated in the human head."

The universe is seen, as in Hegel's universal-historical philosophy, as a totality, that is, as an objectively coherent whole. But Marx understands the merely mental opposites in idealism as expressions and images of real, material opposites: These, too, depended on each other and were in a constant movement of reciprocal influence. This movement is altogether ascending, i.e., it moves as a whole from the simple to the complex and in the process passes through certain levels, to which certain qualitative changes correspond, so that they drive development forward.

According to this view, an objective reality also exists outside and independent of human consciousness in the material movements, on which, however, people (themselves a part of the material) consciously act back. This does not at all mean, however, that people grasp their environment objectively correctly; Marx and Engels want precisely to escape the ideological self-deception, the false consciousness of the environment, hence the problem of the subject-object split:

· The correct understanding of the laws of motion of phenomena and events can only ever proceed from the analysis of practice and never from an idealistic "quirk", since the latter cannot derive a phenomenon from its material origins.

Freedom does not lie in the dreamed independence from the laws of nature, but in the knowledge of these laws, and in the possibility thus given of letting them work according to plan for certain purposes.

· This already addresses the relationship between the abstract and the concrete (drawing abstract conclusions from practice, developing concrete practice again from the abstract conclusions):

He was a man, and I was a man, and I was a man, and I was a man, and I was a man, and I was a man, and I was a man. I was a very good friend of his," he said, "and I was a very good friend of his, and I was a very good friend of his, and I was a very good friend of his, and I was a very good friend of his, and I was a very good friend of his. He was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man, and he was a man.

· The touchstone for the correctness of assumptions or theories (= relative truth) is then again one's own practice, in which the theory proves to be right or wrong.

The question whether human thinking has objective truth - is not a question of theory, but a practical question. In practice, man must prove the truth ... of his thinking.

This review is necessary, he argues, because the consciousness of man is always determined by his interactions with the environment, that is, by being.

This assumption experiences its strongest effect when one reflects on future social developments; in this sense, any utopianism is rejected. According to a materialist world view, "the production and reproduction of real life" must become the "determining moment in history", labour must therefore be a central category for the individual himself and for social development. Therefore, all social orders are decisively determined by economic laws of motion:

"In the social production of their lives men enter into certain necessary relations independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a certain stage of development of their material productive forces. The totality of these relations of production forms the economic structure of society, the real basis on which a juridical and political superstructure rises and to which certain social forms of consciousness correspond. The mode of production of material life determines the social, political and spiritual process of life in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but conversely their social being that determines their consciousness."

The consequence of this view is a comprehensive critique of religion, law and morality. Marx understands these as products of the material relations in question, to which they are also subject to change. Religion, law and morality would therefore not have the universal validity they claim.

Historical materialism

→ Main article: Historical materialism

Historical materialism is the application of the guiding principles of dialectical materialism to the study of society and its history. According to it, the development of a society can also be explained scientifically: Due to the class struggle, the social relations between the classes are in an uninterrupted movement. The productive forces (labour and means of production) develop over time until they come into conflict with the relations of production (division of labour and distribution of property). Marx sees the relations of production as "fetters" which form an obstacle to the further development of the productive forces. The underclasses are always intent on changing the relations of production to their advantage. As a result, new ruling classes come into being and the class struggle begins again.

Marx distinguishes between the following historical stages of development of society:

· tribal or primitive society, also primitive communism

· Slaveholding society

· Feudal society

· Capitalist society

After the overcoming of capitalism inevitably follow:

· Socialism

· Communism

The history of a society is a (natural) development from the simple to the complex, from the lower to the higher. That is why communism is inevitable in the future. In Marx's view, capitalism leads to ever greater crises. Socialist society will therefore replace capitalist society, just as capitalist society replaced the feudal order. The class struggle ends only in the communist order, in which the opposition of master and servant is abolished.

Political economy (analysis of capitalism)

→ Main article: Marxist economic theory

Having developed an epistemological position with dialectical materialism, and a general theory of history and society with historical materialism, Marx had come significantly closer to his analysis of contemporary concrete society. The next necessary step for him was now to study the economic laws of motion in capitalist societies, since, according to the theory of historical materialism, the mode of production of a society is significant for its development. The heart of his work is the Critique of Political Economy in the three volumes of Capital. The laws of exploitation in ruling capitalism, the emergence of modern class society, and the process of concentration of capital are analyzed in both micro- and macroeconomically differentiated ways. In doing so, Marx drew on preliminary work in national economics, e.g. by Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Value theory, impoverishment theory and crisis theory are important components of this analysis.

G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831)

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872)

History

→ Main article: History of Marxism

The theoretical edifice designed by Marx and Engels was and is the point of reference for a wide variety of political and scientific schools of thought. Marxism first found practical application in the workers' movement of the 19th century, above all in the German Social Democracy, which made the theories of Marx and Engels the basis of its first programs and member training. Then, following Marx, Lenin developed his theory of imperialism, which, together with the ideas of Marx and Engels, became the new state ideology of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution of 1917. Lenin, however, did not see himself as the founder of a new current, but as a defender of Marxism. After Lenin's death, however, people generally spoke of Leninism, which represented a Marxism adapted to Russian conditions. Later, Joseph Stalin changed Leninism with the theory of "socialism in one country" to the so-called construct of Marxism-Leninism.

This Marxism-Leninism determined the so-called real existing socialism after 1945 in large parts of the world, especially in Eastern and Central Europe, and also had a strong influence on China, Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam. Whether and to what extent this can still be derived from the basic ideas of the "classics" or represents an "aberration" is one of the most controversial questions within Marxist theory formation. The practical politics of these countries is still dominated by Stalinism, especially in North Korea. Today, the Gulag regime is widely classified as a totalitarian system and rejected by almost all Marxists. Against the different ideologies of Stalin and Mao, Trotskyism, developed by Leon Trotsky, also claims the true heritage of Marx and Lenin respectively with its theory of "permanent revolution".

In demarcation to Stalinism and fascism, the works of the Frankfurt School emerged since the early 1930s, which attempted to apply Marx's ideas to the changed political-economic conditions of modernity and, in part, to combine them with psychoanalysis.

Liberation movements in the "Third World" often developed into political systems, such as those still in place today in China (formerly Maoism), Vietnam or Cuba.

The 1960s saw the emergence of various forms of neo-Marxism, Eurocommunism (especially operaism and Titoism), and democratic socialism, particularly in the context of the worldwide student movement, the Western European workers' strikes, and the so-called liberation movements in the "Third World."

History of Marxist Organizations

See also: Communist Party

The writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are still the theoretical framework for various organizations and parties in all parts of the world.

In many European states, smaller organizations were formed first, and later, parties whose history shows parallels. With the rise of National Socialism, many organizations were dissolved and forced into resistance; after 1945, Marxist organizations found themselves primarily in a confrontation with the pluralistic democracy of the West and social democracy on the one hand, and "real socialism" and the CPSU on the other. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a post-Soviet Marxism developed, primarily in Russia.

Leon Trotsky (1879-1940)

Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Marxism?

A: Marxism is a set of political and economic ideas developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Q: What are the main classes in Marxist theory?

A: The two main classes in Marxist theory are the working class and the ruling class.

Q: How does Marxism view exploitation?

A: According to Marxism, the working class is exploited by the ruling class.

Q: What is meant by 'dictatorship of the proletariat'?

A: The 'dictatorship of the proletariat' refers to a situation where workers revolt and take over ownership of factories and materials.

Q: What is communism according to Marxists?

A: Communism, according to Marxists, is a stateless, classless society with free enterprise.

Q: How do social democrats view Marxist ideas?

A: Social democrats believe that Marxist ideas can be achieved through what Marx called 'bourgeois democracy'.

Q: How do different Marxist political economists differ on their definitions of capitalism, socialism and communism?

A: Different Marxist political economists have very fundamental differences on their definitions of capitalism, socialism and communism which sometimes lead to intense arguments between them.

Search within the encyclopedia