Mali

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Mali (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/NAME-German

Mali (German [ˈmaːli], French [maˈli], officially Republic of Mali) is a landlocked country in West Africa. About 19.55 million people live in the approximately 1.24 million km² state (as of July 2020). Its capital is Bamako. Most of the population lives in the southern part of the country, which is crossed by the two rivers Niger and Senegal. The north extends deep into the Sahara and is hardly populated.

In the territory of present-day Mali, three empires existed throughout history that controlled trans-Saharan trade: the Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire, after which the modern state is named, and the Songhai Empire. In Mali's golden age, Islamic scholarship, mathematics, astronomy, literature, and art flourished. In the late 19th century, Mali became part of the colony of French Sudan. Along with neighboring Senegal, the Mali Federation gained independence in 1960. Shortly thereafter, the federation broke up, and the country declared itself independent under its current name. After a long period of one-party rule, a military coup in 1991 led to the adoption of a new constitution and the establishment of a democratic multi-party state.

In January 2012, the armed conflict in northern Mali escalated again. In the course of this, the Tuareg rebels proclaimed the secession of the state of Azawad from Mali. The conflict was further complicated by the March 2012 coup and later fighting between Islamists and the Tuareg. Faced with territorial gains by the Islamists, Operation Serval began on January 11, 2013, during which Malian and French troops retook most of the north. The UN Security Council is supporting the peace process with the deployment of MINUSMA.

The main economic sectors are agriculture, fishing and, increasingly, mining. The most important mineral resources include gold, of which Mali is Africa's third largest producer, and salt. About half of the population lives below the poverty line. The country ranked 184th in the 2019 Human Development Index.

Mali has long traditions in the cultural sphere. Especially in music, dance, literature and visual arts, it has an independent cultural life that is known far beyond its borders.

Mali is a landlocked country in the interior of West Africa with an area of 1,240,192 square kilometres, of which 20,002 km² is water. It is located in the Greater Sudan as well as the Sahel. Mali shares its 7243 kilometre land border with seven neighbouring countries. In the northeast and north with Algeria (1376 kilometers long), in the northwest with Mauritania (2237 km), in the east with Niger (821 km) and in the southeast with Burkina Faso (1000 km). Mali is also bordered by Senegal (419 km) to the west, Guinea (858 km) to the southwest, and Côte d'Ivoire (532 km) to the south. North of the Niger Arc lies the Sahara Desert, which covers two-thirds of the country.

Relief

The most common type of landscape in Mali is the plain. The monotonous, vast plains such as the Kaarta, the Gourma or the Gondo plains are only locally broken up by flat table mountains or dune formations. The south of the Affolé, the Mandingo Plateau, the Bandiagara Plateau or the Mahardates Plateau have subsoils of sandstone. They are diversely indented by erosion and reach altitudes between 300 and 700 meters above sea level. In some regions, the subsoil consists of the ancient rocks of the African Shield, which tends to be expressionless and wide valleys: In the west and east of the country, in the southwest of the Affolé, in the Bambouk, in the Adrar of the Ifoghas and in the foothills of the Tamboura stage. Dune landscapes, whether the dunes are of fossil or recent origin, cover much of the north and extend into the Kaarta in the south. Notable dune landscapes are found in the Hodh, the Erg of Niafunké, the Gourma, the Gondo plain, the Ergs of Azaouad, of Erigat, of Mreyyé or the Erg Chech. While the fossil dunes are mostly parallel, chaotic and very mobile dune fields are common in the Aklé Aouana. Stratified steps forming steep slopes hundreds of meters deep are generally characteristic for West Africa, for Mali the Bandiagara step, the Tamboura step or the Affolé step can be mentioned. The few uplands of Mali are dolerite formations that rise above the plateaus. These include the elevations of Soninke. The highest mountain in Mali is Hombori Tondo at 1153 m.

Geology and soils

Mali lies entirely on the Lower African part of the Gondwana Urcraton. It is dominated by basin and sill structure, with most of Mali lying in the Taoudenni Basin, which extends from the Niger inland delta to the middle Sahara. The sills surrounding the basin consist of uplifts of the crystalline Urcraton. It is frequently overlain by sandstone formed between the Paleozoic and Cenozoic eras by several phases of seawater inundation. Tertiary deposits occur less frequently. Since Mali, like the entire Sahel, belongs to the rim-tropical zone of excessive land formation, extensive hull surfaces interrupted by inselbergs are typical. Laterite crusts, which can be up to several meters thick, have formed widely on the surface of sediments. The youngest geological formations run parallel in a northeast-southwest direction. They are ancient dunes formed in the Late Pleistocene, up to 30 m high and stabilized by savanna vegetation.

As far as soils are concerned, tropical red earths are the most widespread. They occur on crystalline bedrock or old sedimentary layers and are relatively sterile. Where these soils have formed laterite crusts, sparse vegetation of Combretaceae thrives. In pediment areas, weathering material may accumulate and form suitable soils for agriculture. Fersiallites, reddish-brown lessivated soils on eolian sands, are also common and form layers of 2 to 3 meters. They contain little humus and are susceptible to soil degradation by humans. With appropriate fertilizer application, they are suitable for millet or cotton cultivation. The northern Sahel is dominated by subarid brown soils, which on the one hand absorb the infrequently falling precipitation well, but on the other hand are prone to erosion. This soil, which is often overgrown with grass, is of great importance for nomadic pasture farming. The desert regions are characterized by raw soils, which have been formed by physical weathering and hardly contain any organic matter. Along the rivers, especially in the floodplains and in the inland delta of the Niger, gley soils and vertisols occur. They have high fertility but carry the risk of salinization and crevice formation during drought. They are suitable for growing sorghum, rice, vegetables and other crops.

Waters

The Niger is the most important river of West Africa, it crosses Mali on a length of about 1700 km. Coming from Guinea, it enters the territory of Mali in the southwestern tip of the country and forms a large inland delta after Ségou. At Mopti it takes in its largest tributary, the Bani, and shortly thereafter splits into two arms, the Bara Issa and the Issa Ber. Here is an alluvial plain of about 100,000 km², covered by numerous shallow, seasonal lakes. Shortly before Diré the two arms join, at Timbuktu the course of the river turns towards the east and at Bourem towards the southeast.

The Senegal River is the second important river in the region. It is formed at Bafoulabé by the confluence of the Bafing and Bakoye rivers. On its way through the western part of Mali, the Senegal River still receives the water of Falémé, Kolimbiné and Karakoro.

The year-round lakes are located on both sides of the Niger and are called Niangay and Faguibine. The latter, with a surface area of 590 km², is the largest lake in the country during the rainy season. The numerous seasonal lakes fill with water in the rainy season, the most important of which are called Débo, Fati, Teli, Korientze, Tanda, Do, Garou and Aougoundou. Due to the decreasing rainfall since the severe droughts of the early 1980s and especially the construction of dams on the upper Niger, Niangay and Faguibine have recently been drying up regularly.

Fishing in the rivers and lakes forms an important economic sector. The swamps and wetlands that form along the Niger during the rainy season provide habitats for numerous bird species.

Climate

Mali's climate is primarily influenced by the country's location at the transition zone between the alternating humid savannah in the south and the fully arid Sahara in the north. The interaction between the northward-moving inner-tropical convergence zone in summer and the dry northeast trade winds (harmattan) in winter gives all regions of the country a distinctive division into dry and rainy seasons. The dry season falls in winter and the rainy season in summer. Average annual precipitation decreases from over 1200 millimeters in the south to less than 25 millimeters in the north. Large-scale agriculture is practiced almost exclusively in the south because of the climatically more favorable conditions. In the north, there are only small agricultural areas in the oases.

Not only the average annual rainfall, but also the number of rainy days per year, the length of the rainy season and the regularity of rainfall are much more favourable in the south than in the north. In Sikasso it rains on average on 97 days per year, in Bamako on 76 days, in Timbuktu on 29 and in Kidal on 18 days per year. While in Kidal well over half of the annual rainfall occurs in July and August, the south enjoys a rainy season that begins in May, peaks in August and subsides in October. The further north you go, the more the precipitation falls in the form of short, heavy and localized thundershowers. This further complicates farming, as crops often wither between downpours, forcing farmers to make several sowing attempts.

The average annual temperatures in Mali are between 27 °C and 30 °C. They are largely independent of the geographical latitude. However, the annual amplitudes are significantly higher in the north than in the south: in Gao or Timbuktu, the summers are hotter with average temperatures of up to 35 °C and the winters are colder with January temperatures around 20 °C. In Bamako, on the other hand, average temperatures range from 25 °C in winter to 32 °C in April. Extreme temperatures are reported from places on the edge of the Sahara: they are close to freezing on cold winter nights and close to 50 °C in the shade on summer days. Temperature amplitudes of 30 °C within one day are normal there.

The amount of rainfall in a year depends to a large extent on how far north the inner-tropical convergence zone moves and how uniform it is. If it is not steady but wavy or interrupted, less rain falls or the rainy season begins later. If there are several years in a row with unfavourable characteristics of the intra-tropical convergence zone, droughts occur. This phenomenon occurs at irregular intervals in the Sahel. Since the 1960s, however, droughts have become more frequent. A long-term decrease in precipitation can also be demonstrated for this period. This is explained by reduced evaporation in the interior tropics due to environmental degradation. In the future, some scientists expect that rainfall in Mali will continue to decrease and that vegetation zones will shift southward. In this case, the impact on agriculture and food security would be severe.

Climate diagrams of Sikasso, Bamako (southwest) and Timbuktu (northeast)

| Climate diagram of Sikasso (1950-2000)

Source: World Meteorological Organization, Hong Kong Observatory (1961-1990). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram of Bamako (1950-2000)

Source: World Meteorological Organization, Hong Kong Observatory (1961-1990). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram of Timbuktu (1950-2000)

Source: World Meteorological Organization, Hong Kong Observatory (1961-1990). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cities

Mali is home to some of the oldest cities in West Africa. Djenné developed from the 9th century through immigration of Soninke from disintegrated Ghana into a trading centre that experienced its peak in the 13th century and whose architecture still serves as a model for the villages of the Niger inland delta. Timbuktu, located on the southern edge of the Sahara, emerged from the 12th century as one of the region's most important cities, benefiting from its location at the northernmost point of the Niger Arc. While these old cities show declining populations, Mali as a whole shows rapid urbanization, allowing the new urban centers to grow rapidly. In addition to generally high population growth, rural exodus due to deteriorating ecological conditions, drought, or political instability contributes to rapid urbanization. While 9% of Malians lived in cities in 1965, this figure is expected to rise to about 41% in 2015.

By far the largest city in the country is Bamako, which has grown from a population of 6500 in 1908 to over 1.8 million in 2009. The city is the governmental and administrative centre of the country and serves as a bridgehead abroad, especially for development aid. However, it has no cross-border significance. Other important cities are Sikasso (2009: 226,618 inhabitants), Ségou (133,501 inhabitants) and the centre of Malian cotton processing Koutiala (75,000 inhabitants in 1998). Due to the influx of drought refugees, Mopti (81,000 inhabitants in 1998, 120,786 in 2009) and Sévaré have grown rapidly. Northern Sahel cities such as Timbuktu (30,000 inhabitants in 2005, 54,629 in 2009) or Gao (86,353 in 2009) are affected by out-migration, especially of young people.

See also: List of cities in Mali

flora and fauna

The vegetation in Mali is the result of centuries of human intervention. Natural vegetation is now only present in narrowly defined areas. The cultivated landscape, which has been created through grazing, agriculture and slash-and-burn agriculture, can be divided into four zones, depending on the amount of rainfall. With few exceptions, the plants in these zones have in common that they sprout at the beginning of the rainy season and shed their foliage or let the above-ground part die in the dry months.

The area of dense to open dry forests in the southern part of the country is dominated by tree species such as kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra), shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxa), African baobab (Adansonia digitata) or ana tree (Faidherbia albida). All these trees are intensively used by humans. Combretum woody plants thrive on less favourable soil. Horst grasses such as Hyparrhenia, Pennisetum, Loudetia and Andropogon species form the grass layer. North of the dry forests, where annual rainfall is less than 600 mm, the Sahelian briar savanna spreads. Various acacia species, desert date (Balanites aegyptiaca) or Combretum glutinosum, and the grass species Cenchrus biflorus or Aristida mutabilis dominate. Eragrostis tremula often colonizes areas where millet has been cultivated. This savanna is the Tiger Bush; there, areas with and without vegetation alternate in a striped pattern.

The border between thorn tree savannah and northern Sahel lies at 250 to 100 mm annual precipitation. Acacia species, shrub species such as Leptadenia pyrotechnica or the important forage plants Maerua crassifolia or toothbrush tree (Salvadora persica) still thrive in humid lowlands of the northern Sahel. The Sahara begins where the annual precipitation falls below 100 mm. In these areas, Acacia species occur only in wadis. In favourable locations, horst grasses such as Aristida pungens, Aristida longiflora or Panicum turgidum thrive.

Species endemic to Mali are Maerua de waillyi from the caper family, Elatine fauquei from the Tännel family, Pteleopsis habeensis (winged seed family), Hibiscus pseudohirtus (mallow family), Acridocarpus monodii (mallow family), Gilletiodendron glandulosum (legume family), Brachystelmam edusanthernum (genus Brachystelma), Pandanus raynalii (screw tree family).

Due to overhunting by locals and other hunters, desertification of large areas with severe droughts, and ongoing cultivation and competition with grazing animals, larger wild animals in particular are much rarer in Mali than in many other African states. As in Mauritania, extinction rates for populations of mammals in Mali have historically been very high compared to other African states, despite the low population density.

In total, about 140 species of mammals are native to Mali. Numerous species of large mammals have become extinct, including the formerly common sable antelope and the Mendes antelope (which may still occur in the border area with Mauritania), or have been reduced to small remnant populations. The West African giraffe originally occurred over much of central Mali, but was reduced by intensive hunting to a remnant population in the border area with Niger and is now also considered extinct. About 350 elephants live in the Gourma region in the border area with northern Burkina Faso. The latter are the most northerly population of African elephants and show periodic migratory behaviour in the border area, with the area located in Mali accounting for the greater part of the range. The African Manatee, a species of manatee, is also found in Niger, the Niger Inland Delta, Lake Débo and Senegal. The endangered and internationally protected species occurs regularly, but the populations are declining due to hunting and the deterioration of water quality and should be specially protected in the future.

The chimpanzee is found only in the extreme southwest of the country in the border area with Guinea, where its presence was documented for the first time only in 1977. Their number was estimated at 500-1000 individuals in 1984, but in 1993 a figure of 1800 to 3500 was arrived at. The most important habitats are the forests interspersed with Gilletiodendron glandulosum of the legume family, which in the Gilletiodendron forest provide about 60 plant species edible to chimpanzees. The groups are larger there than in those associations living in the savannah. The most important protected area is also the Réserve faunique du Bafing, established in 1990. Other primates found in Mali are the hussar monkey, the western green monkey, the anubis baboon, as well as the Guinea baboon (only in the far west) and the Senegal galago. In the past, lions and cheetahs, among other predators, were found in Mali, but their populations continued to decline, so that today they are no longer present, as is the African wild dog, even in the protected areas. Smaller predators such as the pale fox, sand cat, hawk cat, some creeping cats and martens continue to occur in Mali. Other mammals include some species of smaller antelope, the maned goat, aardvark and hippopotamus, besides numerous small mammals live in the country.

According to BirdLife International, a total of 562 bird species have been recorded for Mali, 117 of which are waterbirds. 229 species are classified as migratory birds. Numerous bird species live mainly in the inland delta of the Niger, in this area also many migratory birds from Europe spend the winter. Worth mentioning is the Mali amaranth, which is occasionally listed in guidebooks as endemic to Mali, but also occurs in neighbouring countries. Mali's endangered birds include larger ground-dwelling birds such as the African ostrich, bustards such as the Arabian bustard and the Nubian bustard, and guinea fowl.

Among Mali's reptiles, there are over 170 species of lizards, including monitor lizards and thorn-tailed agamas, and over 150 species of snakes. These include vipers such as the puff adder, various sand rattle vipers and the desert horned viper, as well as venomous snakes such as several cobras and the boomslang, which is present in the south. The Northern Rock Python is also part of the herpetofauna of the country. The Niger and other rivers are also home to crocodiles, especially the Nile crocodile, as in most major rivers in Africa. Besides these species, 15 species of turtles have also been recorded for Mali.

Mali's rivers and lakes are inhabited by over 140 species of fish, including 18 species of catfish, 14 species of tetra, 9 cichlids (including the Nile tilapia, Sarotherodon galilaeus and Coptodon zillii) and 4 carp fish. Mali's largest fish is the plankton-feeding African bonecone.

Termites are important for the ecosystems of the Sahel, loosening the soil and forming humus. The burrows of the species Cubitermes fungifaber are particularly striking. The weaver bird species are dreaded pests in the rice fields. Migratory locusts are of even greater concern to the population. The desert locust, which has its breeding grounds in the Maghreb, can migrate in huge swarms across the Sahara into the Sahel in years with sufficient rainfall and destroy natural vegetation as well as crops.

The only national park in Mali is the Boucle du Baoulé National Park in the west of the country, about 200 km north of Bamako. It covers an area of 5430 km² and serves to protect hippos, giraffes, waterbucks, roan antelope, giant eland and lyre antelope as well as warthogs, plus a corresponding flora. However, its forests are just as endangered by agricultural and pastoral overuse as those of the adjacent Réserve de Fina to the south.

See also: List of endangered species in Mali

Satellite image of Mali

The Bandiagara stage

The Hand of Fatima rock massif near Hombori

Dry forest with acacias and a baobab between Kayes and Bamako during the rainy season

The Niger at Koulikoro

View of Bamako

Population

Population development

Mali's population is one of the fastest growing in the world. It increases by 3 percent every year. The population has doubled from 2000 to 2020. This is mainly due to the very high fertility rate of 5.8 children per woman. Unlike in many African countries, fertility began to decline about 10 to 15 years later, namely only since the late 1990s - starting from a level of over 7 children per woman. The population is correspondingly young, with 47.3% under the age of 15 in 2019. The median age in 2020 was an estimated 16.4 years. Life expectancy at birth has increased from 29.7 years (1950) to 59.3 years (2019). Taken together, these factors give the country a population growth rate for which there is no prospect of abating, but which cannot be sustained at its rate for much longer. In purely arithmetical terms, Mali would have 43.5 million inhabitants in 2050 if growth remained constant, which is unthinkable given the environmental conditions. Thus, the country is on its way "into a disaster" of major social, demographic and ecological crises.

Migration

The population of Mali is made up of about 30 different ethnic groups. They have different languages and cultures. For the peoples of Mali, migration and mobility have a long tradition. Some of their early empires gained their wealth and power through trading caravans. Nomadism was part of life for many of the country's peoples until recently. The traditional movements of migrants cross borders that were drawn only a few decades ago.

Since the country became independent, it has lost about 3 million citizens to foreign countries. In 2010, more than 1 million Malians lived abroad. That was 7.6% of the population. Among people with higher education, this proportion was twice as high. The main destinations of Malian emigrants include its neighbours Côte d'Ivoire, Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Senegal, as well as France and Spain. In 2010, there were 162,000 foreigners living in Mali. This was 1.2% of the population. Most of them came from neighbouring countries and about 6% were refugees.

The money that emigrated Malians send home has become an important factor in the Malian economy. In 2009, these remittances amounted to $400 million. This was three times as much as six years earlier. The amount of these transfers is equivalent to four times the direct investments of foreign companies, or not quite half the development aid.

Ethnicities

Mali's borders do not run along national or ethnic settlements. They were determined by colonial influences and administrative spaces. Today, Mali is home to peoples who differ in language, religion and other anthropological and ethnological characteristics. These people do not settle in Mali alone, but also in neighboring countries. The assignment to ethnic groups and their designation are partly constructs from the colonial era.

The dominant group in Mali is called Mande, which makes up about 40-45% of the population. This group includes the Bambara (35%), Malinke (5%) and Jula (2%). Their settlements are located in the southwestern triangle of the country. The Sudanese peoples, who reach 21% of the population, include the Soninke or Sarakolle (8%), Songhai (7%), Dogon (5%) and the Bozo (1%). The Volta peoples are represented by about 12%. They settle mainly near the border with Burkina Faso. They include the Senufo (9 %) and Bwa, as well as Bobo (2 %) and Mossi (1 %).

While all these groups live sedentary lives and are of black African origin, the Fulbe (10 %), the Tuareg (6 %) and the "Moors" (3 %) lead nomadic or semi-nomadic lives. Many nomads have had to abandon their traditional life due to climatic changes and warlike conflicts in recent years. The Tuareg in particular are threatened by progressive marginalisation.

Languages

In Mali, 35 languages are spoken, belonging to three different language families, which in turn break down into local variants and dialects. The language boundaries run along ethnic lines. Bambara is the most important of these languages, with an estimated 4 million native speakers; it is considered the lingua franca not only of the country but of the entire region, and has had this role in the past. An estimated 5 million Malians speak Bambara as a second language today. Senufo has an estimated 2 million speakers in Mali alone, and is also widely spoken in neighbouring countries. Other important languages include Songhai (1.5 million speakers), Fulfulde (also 1.5 million), and Maninka (1.2 million speakers). In northern Mali, Tuareg languages and Arabic are widespread; the population there considers Bambara to be a means of power development for sub-Saharan peoples and for this reason refuses to learn the language. Tamascheq and Tamahaq together have around 800,000 speakers in Mali.

Although the French language is only spoken as a mother tongue by a vanishing minority in Mali, it is nevertheless declared an official language by the Malian constitution. Malian law recognizes 13 languages in addition to French as national languages (Bambara, Bomu, Bozo, Escarpment Dogon, Maasina Fulfulde, Hassaniya Arabic, Mamara, Kita Maninkakan, Soninke, Koyra Senni, Senara, Tamascheq, Xaasongaxango) and prohibits discrimination based on language. While parliamentary debates are held in French, court proceedings are usually held in a national language. In any case, documents are prepared in French. Schools also mostly teach in the language of the ethnic group, but French is widely used even in primary school. Higher education is offered in French alone. As a means of increasing social mobility, i.e. as a means of social advancement and regional mobility, the language of the former colonial power is of great importance. It is estimated that 2.2 million Malians can now read and write French.

Religions

Mali is a Muslim country. Between 85% and 90% of the population profess Sunni Islam of the Malikite school of law. A direction of Islam that is widespread in West Africa and insists on the equality of all Muslims gained strong influence in Mali in the 11th century at the latest. The carriers of this variant of Islamization were Berber traders who, as Kharijites, traded with the Sudan zone. For a long time, Islam remained confined to the elite of the urban centers. Ruling families, merchants, and sages had converted to Islam, while the majority of the population adhered to traditional belief systems. Nevertheless, Islamic scholarship flourished in some Malian cities from the 13th century onward. After 1800, Islamic states were formed in West Africa: by Usman dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, or Seku Amadu Bari, who founded the theocratic Massina Empire. In parallel, many young men converted to Islam, which they saw as an alternative to European colonial culture; only with this did Islam penetrate the rural population of Mali. Over time, Mali's Islam incorporated many elements of traditional religions. Sufism in particular gave people space for their ideas of spirits, demons and hidden forces. Even today, religious specialists are influential. They derive their prestige, according to widespread belief, from knowledge of the Arabic script, from knowledge of particularly powerful suras in the Koran, and through a power of blessing (baraka) inherited from their ancestors. Since the 1930s, under the influence of scholars who studied in Saudi Arabia or Egypt, there has been a movement to oppose esoteric practices in Malian Islam. The advocates of hybrid religious practice, however, defend their approach to Islam as walking on two paws. The Sufi tradition of the 11th-century Qādirīya and the 18th-century Tijānīya, as well as intellectual exchanges with other peoples of West Africa, have strongly influenced Malian Islam.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Wahhabism spread in the circles of Malian students and traders who had direct or indirect contacts with the Middle East. During the regime of Moussa Traoré (1968-1991), the country experienced a creeping Islamization. Traoré emphasized Mali's Muslim identity since the 1980s.

Before Islamization, ethnic religions predominated. In their original form, they have been preserved in remote regions of the southwestern part of the country. They serve primarily to maintain rural subsistence society and include ancestor worship, belief in spirits and magic, and the practice of sacrificial offerings and membership in secret societies. Each member of the community passes through various phases, with initiation occurring at the beginning of each. An initiation ritual also precedes each of the next phases. The religious traditions are different for each of the country's numerous ethnic groups.

Christians make up 1-5% of the population according to various sources. Most of them profess the Catholic Church and belong to the Dogon and Bobo peoples. The Malian state respects the freedom of religion enshrined in the constitution. The Archbishop of Bamako, Luc Sangaré, was until his death considered an influential personality who was also respected by Muslims. His successor since 1998 is Jean Cardinal Zerbo. Mali and the Holy See maintain diplomatic relations. The Apostolic Nuncio since March 2019 is Archbishop Tymon Tytus Chmielecki.

Malian society was characterized by respect for those of other faiths until the outbreak of the rebellion, but religious persecution has increased sharply in the recent past.

Education

Until the end of French colonial rule, a modern education system existed only in a few places. Its aim was mainly to train administrators and translators for the colonial administration. After independence, the government of Modibo Keïta made the training of professional personnel for the development of the young state a priority. By the end of the 1960s, at least one-third of boys and one-fifth of girls were attending school. The dictatorship from 1968 onwards brought backward steps in the education system: budgets were cut, the number of teachers decreased, and the teachers' union was subjected to reprisals. By the end of the 1980s, only one in five children could attend school. In the 1990s, education became a priority again. In cooperation with the World Bank, the PRODEC programme was launched, primarily to improve the quality of primary education and enable all children to attend school. The education budget was increased, reaching 30.06 % of total government spending in 2004. Almost three quarters of all children had access to education as a result.

The Malian school system is based on that of other French-speaking countries. Less than 2% of children attend kindergarten (jardin d'enfants). Children start school at the age of six; primary school (premier cycle) lasts six years, followed by a three-year second cycle. After completing this second cycle, pupils can attend a three-year lycée. Academic educational institutions are located in Bamako and Ségou. The Université de Bamako had 80,000 students in 2011. In 2011, the university was dissolved and four institutions were established in its place according to their respective disciplines. Thus, the Université des sciences sociales et de gestion, the Université des lettres et des sciences humaines, the Université des sciences, des techniques et des technologies and the Université des sciences juridiques et politiques as well as the École Normale d'Enseignement Technique et Professionnel were founded in Bamako.

Despite the progress made in the last 15 years, the Malian education system faces numerous problems. Financial constraints cause poor facilities, a shortage of teaching materials and teachers: in 2006, on average, one teacher had to look after 66 pupils. Political crises at home and abroad cause refugee flows that overload local schools. The percentage of students who drop out of school before graduation is very high, and access from the education system is unevenly distributed for cultural and financial reasons: Girls have a much lower chance of education than boys, and rural populations have significantly lower opportunities than urban populations. In 2015, 61.3 percent of all persons at least 15 years old were illiterate (also due to the earlier lower percentage of school attendance).

Outside the formal education system, Koranic schools operate, where the children are instructed exclusively in Arabic and Koranic verses, and where they have to earn their own living by begging. In Médersas, the children are taught religious subjects, but also French, reading, writing and arithmetic.

Health

Mali's health system is poorly developed, especially outside the capital Bamako. There are 5 doctors and 24 hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants (as of 1999). Due to malnutrition, contaminated drinking water and poor hygiene, infectious diseases such as malaria, cholera and tuberculosis occur regularly. 43 % of the population is able to see a doctor in case of illness or injury. In 2006, the prevalence of HIV in the population aged 15-49 was found to be 1.3%, or about 66,000 people. This figure represents a decrease from the late 1990s, when HIV prevalence was estimated to be as high as 3%. Almost two-thirds of the population are aware of the modes of transmission of HIV. Despite this, (perceived) HIV-positive people are socially marginalised. High blood pressure, which occurs with above-average frequency in Africa, affects 35 % of men in Mauritania, the highest figure in Africa, and 33.2 % of men in Mali (global figure: 24 %); among women, Mali has a very high rate of 29.5 % (global figure: 20 %). Infant mortality has been greatly reduced. In 1950, 43% of children died before their 5th birthday; in 2018, the figure was around 10%. The infant mortality rate is 6.3 %.

Mali is one of the countries where the circumcision of young girls is most widespread. In 2006, 85% of women reported being circumcised. The same number of women said they wanted to have their daughters circumcised. The practice is independent of income, education level or religion: two-thirds of women of the Christian religion are circumcised. Tuareg or Songhai women are less than one-third circumcised, while the proportion of circumcised women among the Bambara or Malinké is 98%. Because the procedure is performed before the age of 5 and usually by a traditional circumciser rather than a medical professional, complications are common. Nevertheless, circumcision is so firmly rooted in the tradition of the peoples of Mali that all initiatives to abolish circumcision have led only to a slight decrease in this practice.

Great Mosque of Djenné

A Bambara girl in Mopti

Public school in Kati, Koulikoro region, December 2002

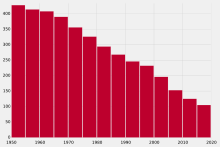

Trends in infant mortality (deaths per 1000 births)

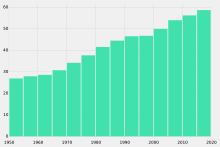

Development of life expectancy

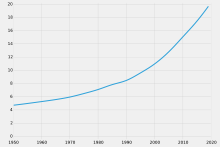

Population development in millions of inhabitants

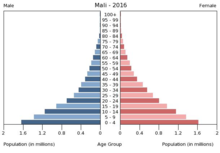

Population pyramid of Mali (2016)

Bamako Cathedral

Questions and Answers

Q: Where is Mali located?

A: Mali is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Algeria to the north, Niger to the east, Burkina Faso and the Côte d'Ivoire to the south, Guinea to the southwest, and Senegal and Mauritania to the west.

Q: What are the physical features of Mali?

A: Mali's physical features include the Sahara desert in the north, with the Niger River and Sénégal River in the southern part of the country.

Q: What is the population of Mali?

A: As of a July 2011 estimate, Mali has a population of approximately 14,000,000 people.

Q: What is the total area of Mali?

A: Mali has a total area of 1,220,190 square kilometres (471,120 sq mi).

Q: Where is Mali's capital city located and what is its population?

A: Mali's capital and most populated city is Bamako.

Q: Which languages are spoken in Mali?

A: The official languages of Mali are French and Bambara, but several other languages are also spoken, including Fula and Arabic.

Q: What countries borders Mali?

A: Mali is bordered by Algeria on the north, Niger on the east, Burkina Faso and the Côte d'Ivoire on the south, Guinea on the southwest, and Senegal and Mauritania on the west.

Search within the encyclopedia