Maginot Line

![]() Map with all linked pages: OSM | WikiMap

Map with all linked pages: OSM | WikiMap

Western Campaign

Battle of the Netherlands

Maastricht - Mill - The Hague - Rotterdam - Zeeland - Grebbeberg - Afsluitdijk - Bombardment of Rotterdam

Invasion of LuxembourgCobbler line

Battle of BelgiumFort

Eben-Emael - K-W Line - Dyle Plan - Hannut - Gembloux - Lys

Battle of FranceArdennes

- Sedan - Maginot Line - Weygand Line - Arras - Boulogne - Calais - Dunkirk (Dynamo - Wormhout) - Abbeville - Lille - Paula - Fall Red - Aisne - Alps - Cycle - Saumur - Lagarde - Aerial - Fall Brown

The Maginot Line ([maʒi'noː], French Ligne Maginot) was a defensive system consisting of a line of bunkers along the French border with Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany and Italy. The system is named after the French Minister of Defence André Maginot. It was built from 1930 to 1940 to prevent or repel attacks from these neighboring countries or the hegemonic powers of Germany and Italy that might attack through their territories. In addition, the southern tip of Corsica was fortified.

Usually only the part along the German border is called the Maginot Line, while the term Alpine Line is used for the half to Italy.

The idea of such a line of defence already existed immediately after the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. In 1874, the French began building the Barrière de fer ("Iron Barrier"), which consisted of numerous forts, forts and other similar structures.

These were bricked and proved no match for the brisance shells that emerged in 1890.

In the second half of the First World War, the Germans had built the Siegfried Line (= Hindenburg Line) in order to shorten their front line, to save material and men, and to be able to withstand the increasing Allied superiority after the American entry into the war. The Allies were not able to break through this defensive structure in places until the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (26 September to 11 November 1918 in the Verdun sector). The Maginot Line was to become a similar defensive structure.

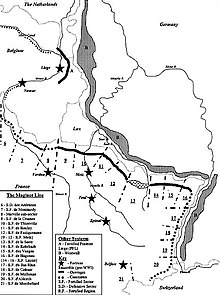

Map of the Maginot Line

Prehistory of the French fortress construction

The construction of defensive fortifications has a long tradition in France. Historically, this approach to defense was shaped above all by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban. They prevented capture for centuries.

History

Planning and construction

One of the main reasons for France's defensive orientation vis-à-vis Germany was its demographic development: due to its stagnating population, France already found it increasingly difficult during the decades after 1870 to maintain a mass army, if necessary also offensively oriented, at a numerical level that could compete with its expanding neighbor Germany. Horrendous war losses in 1914-1918 - some 1.3 million Frenchmen died - further worsened France's position vis-à-vis its neighbor, which, at nearly 70 million, had almost 30 million more inhabitants than France. Immediately after the end of World War I, the French government (1917-1920 under Georges Clemenceau) commissioned the General Staff to conduct a study on the defense of France's borders in order to be prepared against a possible renewed German invasion after the experience of 1914. The best known people involved in the study were Marshals Ferdinand Foch, Philippe Pétain and Joseph Joffre. Foch was averse to static defence systems, Joffre advocated a solution modelled on the forts of Verdun, Toul and Épinal, while Pétain favoured a linear and fortified front.

Paul Painlevé, Minister of War from November 1925 to July 1929, set up two commissions: The Commission for the Defence of Frontiers (Commission de défense des frontières - CDF), with the task of planning the general layout and organisation of the lines and submitting a cost estimate, and the Commission for the Organisation of Fortified Regions (Commission d'organisation des régions fortifiées - CORF), which was to prepare the results of the CDF for practical implementation.

At the beginning of 1929, the CORF concept was adopted by the Council of Ministers. Painlevé handed over his office to his successor André Maginot in July 1929. Maginot submitted the program to parliament as a bill and had it voted on openly on January 14, 1930. Over 90 percent of the deputies approved it. The decisive factor for the decision to build the Maginot Line was probably the successful defence of France at the fortress ring of Verdun. The German troops were unable to break through this in 1916.

Maginot died unexpectedly in January 1932.

The most important parts of the line were built by 1936. With the increasing threat from the German Reich, the insight into the necessity of the project grew. The cost officially totaled 5 billion old French francs. By November 1936, 1000 kilometres of Maginot Line were considered completed.

The possibility of a massive enemy tank attack was not considered or ignored in the planning. The defenses were planned based on experience from the previous war only to defend against infantry attacks. The most important elements of the Maginot Line were to be newly developed artillery works with retractable turrets, which, equipped with 75 mm calibre guns and 135 mm howitzers, were to be placed at intervals of ten kilometres. The space between the artillery works was to be protected by lightly armed infantry works and casemates. All in all, with only 344 guns and 500 anti-tank guns - in relation to the total length - the defense line was rather poorly equipped in artillery terms. The individual installations were equipped with their own power supply and ventilation system. Larger artillery works had electrically operated light railways. Up to 20,000 workers were employed in the construction of the Maginot Line in the early 1930s (during the Great Depression).

By 1940, 108 artillery pieces had been built, almost half of them on the border with Italy. The Maginot Line, however, was not a continuous defensive line, contrary to what was portrayed in French and German propaganda. Rather, it consisted of a number of independent and isolated fortifications. The infantry works had crews of about 100 soldiers, smaller artillery works had 150-200 men, in larger ones up to 600 men were stationed.

A decisive disadvantage of the Maginot Line was that it was far too manpower-intensive. A Maginot Line extending all the way to the North Sea would have tied up a large part of the French army due to the high manpower requirements and would have made offensive actions impossible. For this reason, the defences were only fully extended as far as Sedan. Individual sections, for example on the Meuse, had been built entirely without artillery works due to financial restrictions. The sections between Sedan and Lauterbourg were very strongly fortified, but on the Rhine side the equipment had not yet arrived everywhere at the beginning of the war, so that here the positions were insufficiently equipped. In addition, the bunker line was not finished everywhere. In the Jura there are casemates whose formwork has not been removed to this day. Because of the high costs of the works in Alsace, other sections had to be neglected. Sometimes even iron sign houses from the First World War were concreted in and converted into observation posts, as in the Sundgau position.

The course of the war on the Maginot Line

In the 1940 attack on France, the German attacking front aimed at the weak points of the line. Part of the Wehrmacht units, similar to the old Schlieffen Plan from World War I, took the route through Belgium and thus bypassed the entire line, while the main attacking force decisively pushed through the line at a weakly developed section in the Ardennes.

The Allies expected the German attackers to be forced to take the route through Belgium because of the fortifications, and moved much of their best formations into Belgium. When the French 1st Army, Belgian Army, and British Expeditionary Force met the Wehrmacht there, it reinforced their view that the German attack would again be through Belgium-while the Germans' fast armored divisions unexpectedly broke through the barely defended Ardennes and bypassed the Maginot Line at Sedan. The bulk of the Allied armies, standing in Belgium and northern France, were trapped by this breakthrough of German armoured units towards the Channel, called the "Sickle Cut". Over 300,000 British and French soldiers, already trapped at Dunkirk, were evacuated across the English Channel to England in Operation Dynamo (known as the Miracle of Dunkirk). The delay in attacking the trapped Allied troops (see Haltebefehl) would later prove to be a crucial mistake by the Germans. France had to capitulate after the construction of a new defensive line failed: the forces remaining to the country were altogether too weak.

Attacked fortifications usually did not withstand bombing by Stukas, direct fire with 8.8-cm flak and the use of shaped charges for long. Often the crews in infantry works without guns had to watch helplessly as the Germans brought up their guns and began direct fire out of range of French machine guns. Resistance often lasted no more than 48 hours, by which time all MGs and anti-tank guns (Paks) had been destroyed, and ventilation proved to be a weak point, frequently failing. For example, the 107-man crew of the La Ferté infantry works in the Montmédy section was killed by accumulated toxic explosive gases, despite wearing gas masks. Both bunkers had no guns and could therefore be quickly put out of action by the attackers. The French had then fled to deeper areas of the infantry works and suffocated there.

Many of the plants on the Maginot Line still flew the French flag after the surrender - the Wehrmacht made no attempt to capture them. The German troops were content to cut off the individual bunkers and works from each other, to confine the crews in their facilities and thus effectively neutralize them. It is likely that parts of the line could have held out for months, but this would have been pointless given the occupation of France. Some of the commanders of various works, including that of the Four à Chaux, nevertheless refused - true to their outmoded and then recognizably pointless motto: "And they won't get through!" - to comply with the surrender and hand over the forts to the Wehrmacht. In a daily order dated July 1, 1940, the Commander-in-Chief of France, General Maxime Weygand, paid tribute to the 22,000 remaining and thus bound defenders of the now meaningless Maginot Line.

The Maginot Line today

Many works (French : ouvrage) of the Maginot line can be visited today - some are or will be restored and include smaller exhibitions. Among them:

- Fort Hackenberg, one of the largest bunker installations of the Maginot Line; served as a prototype for further fortifications of the Maginot Line. It had its own casemate railway; this is still operational today.

- Fort Michelsberg, the artillery piece is located in the Boulay fortification sector between Dalstein and Ébersviller, near Fort Hackenberg (F57320).

- Fort Simserhof near Bitche (German: Bitsch) not far from Zweibrücken.

- Fort de Schoenenbourg near the village of Schoenenbourg south of Wissembourg (Weißenburg).

- Four à Chaux (Fort Kalkofen) near the village of Lembach not far from Wissembourg.

- La Ferté south of Sedan, one of the few forts directly captured in combat by German troops.

- Marckolsheim casemate (Mémorial-Musée) southeast of Sélestat (Schlettstadt).

- Fort Casso near Rohrbach-lès-Bitche.

A counterpart to the Maginot Line was built by Germany in the late 1930s in the form of the Westwall. Also modelled on the Maginot Line, the Czechoslovakian Wall was built from 1935 to 1939.

·

The entrance of the fort Michelsberg

·

Fort de Fermont near Longuyon

·

Entrance to the Schoenenbourg artillery works

·

The main tunnel at Fort Schoenenbourg

·

View from a battery at Ouvrage Schoenenbourg in Alsace. The turrets are retractable.

·

Casemate Grand Lot near Thionville

·

Entrance to the Molvange artillery works

·

Latiremont artillery works

·

The kitchen of Fort Michelsberg

·

The partially restored power station of Fort Michelsberg

·

Abri Helmet Realm

·

Light machine gun, casemate Marckolsheim-South

·

Tank bell at Col de Guensthal near Windstein

US troops reach the Maginot Line (1944)

Destroyed tank tower after the capture by the Wehrmacht in May 1940

Map of the Maginot Line in Alsace

Badge of the fortress troops of the Maginot Line with the motto "On Ne Passe Pas" (loosely translated: "No way through")

Destroyed bunker near Arras in May 1940

Soldiers in a bunker of the Maginot Line 1939

Search within the encyclopedia

.JPG)