Machine

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Machine (disambiguation).

A machine (borrowed from French machine, from Latin machina, this from ancient Greek μηχανή mēchanḗ, German 'Werkzeug', 'künstliche Vorrichtung', 'Mittel') is a technical structure with parts moved by a drive system. Machines are used as technical means of work, especially for mechanical action. In the past, the focus was on the flow of energy and/or material. The flow of information first played a role in precision mechanical devices, but is now important in almost all machines (automation). Attractive goals for the invention of machines were, from the point of view of a worker, an increase in his own strength, time saving, precision, finer processing possibilities and the production of larger quantities of identical products. It also followed that machines and devices would relieve the production worker of physical and mental labor. These modern means of work take over mainly routine and also dangerous work.

Each machine contains individually manufactured parts, such as at least frame and housing. A significant proportion is made up of parts with a standard function; these machine elements are produced separately as mass-produced articles. Fixed machine elements are, for example, screws and seals, movable elements are, for example, gears and levers.

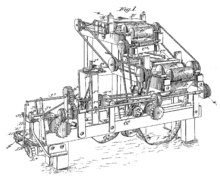

Machine for "rolling" cigarettes

Definitions

Conceptual History

Machines are always products of man. Due to its ancient meaning (cf. "Deus ex machina"), the machine was understood until modern times mainly as a means to a deception - the creation of unnatural, i.e. impossible effects - and only secondarily as an aid to work.

In the Renaissance, a more precise concept developed about mechanisms: mechanisms are complexes of components in which the movement of one element necessarily causes the movement of other elements. They usually have moving components and are considerably more complex than the apparatus (the 'tool').

In this period, a mechanism was primarily a movement, a form of gearing that transmitted forces. Among the most complicated mechanisms was the Grande Complication (Grand Complication) in mechanical-automatic movements. The mechanism of Antikythera, an ancient artifact that replicated celestial mechanics, should also be understood in this sense.

In this period, art (artes mechanicae) also still referred to engineering, and as late as the 19th century, machines driven by water power or horses in mining were called miners' art.

Mechanical basics: simple machine and automaton

The development of classical mechanics as a scientific discipline since the Enlightenment has led to the search for the basic elements of mechanical systems, in the sense of 'atoms', the components that cannot be broken down further - this was already thought of by the ancient Greek engineers (Aristotle): this is how the simple machines are defined, namely rope and rod, pulley, lever, as well as inclined plane (in antiquity still the screw, but this can be modelled as rod and inclined plane).

More or less complex mechanisms occur in practically all engineering sciences and technical disciplines. The spectrum of possible machines ranges from a simple device with connected moving parts (mechanisms) to complex structures (plants) stretching over kilometres.

In technical applications, machines usually have a drive (for example, a motor) that supplies energy more or less continuously. The machines work with this energy, which is why they are called working machines. The engine and other machines that convert various forms of energy into mostly rotating kinetic energy are called prime movers.

Because the machine, if it has a continuous drive, divides work processes into a sequence of repeatable steps, its meaning overlaps with that of the automaton. It can replace (unpredictable) actions of humans or animals with predictable activities (an algorithm). The αὐτόματος automatos, "which moves of its own will", is originally a toy built on gears, also illusionistic - but it corresponds to the mechanistic models of the Enlightenment, which also seeks to explain nature as an inevitable, determinable sequence.

Development of the definition in industrialization

19th century:

Connections of resistant bodies, which are so arranged that by means of them mechanical forces of nature can be compelled to act under certain movements (Reuleaux).

The connection of bodies to a machine does not exclude all and any movement, but only prevents the movements that

are unnecessary and disturbing

for the purpose of the machine, so that the purposeful movements remain as the only possible ones.

20th century:

Standardization efforts are aimed at distinguishing

between machine, device, apparatus, automaton, tool, instrument and plant:

- Machine as a primarily energy- or force-converting system or structure,

- a simple machine consists of only one or very few elements and can often be called a tool

- a prime mover provides mechanical energy (kinetic energy)

- a working machine absorbs mechanical energy (kinetic energy)

- Device as a primarily signal-converting or information-processing technical entity,

- Apparatus is primarily a technical structure that converts material,

- Automaton as a machine that can run automatically

- Tools are devices that do not function independently, but are either guided by hand or are part of machines,

- Instruments are devices that do not serve to implement work, but to display it,

- Plants are complex systems consisting of machines, apparatus, devices, tools or instruments.

End of 20th century:

In Europe, the machine is defined in the Machinery Directive.

As a result of electronization and automation in the 20th century, the concept of machine has expanded to include computer programs that simulate machines.

In engineering technology, however, a distinction is

usually made between mechanical machines and electronic automata.

The European Machinery Directive as a definition aid

Directive 2006/42/EC (Machinery Directive) regulates a uniform level of protection for the prevention of accidents when placing machinery on the market within the European Economic Area (EEA) as well as Switzerland and Turkey. It also defines what must be considered a machine:

According to 2006/42/EC Article 2 Para. a (or transposition into national law, by 9th ProdSV § 2, Para. 2) "machine" means

- an assembly, fitted with or intended to be fitted with a propulsion system other than directly applied human or animal power, of interconnected parts or devices, at least one of which is movable and which are assembled for a specific application;

- an assembly within the meaning of the first indent, lacking only the parts which connect it to its place of use or to its sources of energy and propulsion;

- a ready-to-install assembly within the meaning of the first and second indents which is functional only after being mounted on a means of transport or installed in a building or structure;

- an assembly of machines referred to in the first, second and third indents or of partly completed machines referred to in point (g) which, in order to function together, are arranged and controlled so that they operate as a whole;

- an assembly of linked parts or devices, at least one of which is movable, which are joined together for lifting operations and whose sole source of propulsion is directly applied human effort.

A machine is essentially functional as a stand-alone unit independent of its environment, while its individual components are usually not usable in a meaningful way independently of the machine.

However, the scope of the Machinery Directive does not cover "machinery whose sole source of power is directly applied human effort, with the exception of machinery used for lifting loads ..." (2006/42/EC Article I(2a)). This restriction of the term thus excludes many devices that are machines in everyday language. The text of the regulation defines further exceptions and additions.

The new version of the Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC also lists partly completed machinery characterised by the fact that it is intended to be incorporated into or assembled with other machinery or other partly completed machinery in order to form, with the latter, machinery within the meaning of the Directive.

Examples, with the consequent associated requirements of the EU Directives:

- A clamping device for workpieces that draws its energy and signals from a higher-level machine is not a machine.

Reason: no function without higher-level machine. (RL: Declaration of incorporation) - The pitchfork is not a machine.

Reason: no attachment to machine (intended use), no moving parts, operated by muscle power only, no stored energy. (RL: no marking)

More specific definitions

- A machine is intended to perform a task mechanically and to convert the input energy into movement (= prime mover) with corresponding force development on the output or working side of the machine (= driven machine).

- Machining of a material (drilling, turning, milling) with exact definition of the movements of tool and workpiece: machine = machine tool.

- Machine designed and built for a special purpose: Machine = special purpose machine

- Machines whose purpose is the conversion of a supplied energy into motion: machine = motor

- Machines that serve to restore physical abilities: Machine = prosthesis

- Machines that are installed in buildings. Machine = Technical building equipment system, e.g. ventilation systems, lifts, refrigeration machines, air conditioning systems, recooling plants.

Chronological table / historical examples

- the systematic use of lever and wheel was decisive for the development of machines

- ca. 700 B.C.: Babylonian ladle works in Assyria, mechanical engineering works

- ca. 550 B.C.: lathe, first machine tools

- ca. 340 B.C.: Definition Aristotle: Lever, screw are called 'machine'.

- ca. 50 AD: Heron of Alexandria first heat engine

- 15th century: Machine = 'work of art' (artist engineers example Leonardo da Vinci).

- 16th century: Machine = 'technical device' (engineering example Galileo Galilei).

- 17th century: Simulations of nature with mechanical models, nature = 'machine' (for example in Descartes).

- 1712: Thomas Newcomen first usable steam engine (heat engine), 1769 considerably improved by James Watt

- 1789: The French Revolution changes the attitude towards mechanics and the machine Liberation of man from slavery also by rejecting the veneration of antiquity

- around 1900: distinction special machine, machine tool.

- 1957: Integration of the machine: man-machine system

engine room

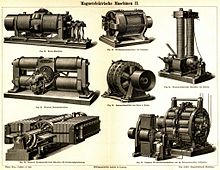

Meyers: Magnetic-electric machines II (E-Motors) around 1890

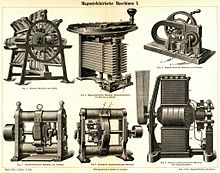

Meyers: Magnetic-electric machines I (E-motors), around 1890

Machine tool (pillar drilling machine)

automatos humanoides , Centre International de la Mécanique d'Art, Sainte-Croix (CH)

Ancient Roman pump, 1st/2nd century, Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España, Madrid

See also

- Automat (computer science)

- List of topics mechanical engineering

- Objectified work

Search within the encyclopedia