Lviv

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Lviv (disambiguation).

![]()

Lemberg is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Lviv (disambiguation).

Lviv, German Lemberg (Ukrainian![]() Львів Lviv [lʲʋiu̯], Polish Lwów [lvuf], Yiddish לעמבערג [lɜmbɜrk], Armenian Լվով, Russian Львов Lvov [lʲvov]) is a city in western Ukraine with about 730,000 inhabitants. It forms the main upper center of western Ukraine, is the capital of the Lviv Oblast district of the same name, and (as of 2015) is the seventh largest city in Ukraine. In addition to the city of Lviv with its six city districts, the city administration is also responsible for the city of Vynnyky and the two settlements of urban type Bryukhovychi and Rudne.

Львів Lviv [lʲʋiu̯], Polish Lwów [lvuf], Yiddish לעמבערג [lɜmbɜrk], Armenian Լվով, Russian Львов Lvov [lʲvov]) is a city in western Ukraine with about 730,000 inhabitants. It forms the main upper center of western Ukraine, is the capital of the Lviv Oblast district of the same name, and (as of 2015) is the seventh largest city in Ukraine. In addition to the city of Lviv with its six city districts, the city administration is also responsible for the city of Vynnyky and the two settlements of urban type Bryukhovychi and Rudne.

Lviv is located on the main European watershed, the border of which is formed by a hill in the city. South of it rivers flow into the Black Sea, north into the Baltic Sea. The canalized Poltwa River, which flows through the city underground, flows to the Bug River. The city is located on the Lwiwske Plate (Львівське плато), which is part of the Podolian Plate, about 80 kilometers east of the border with Poland.

Lviv has been characterized by the coexistence of several ethnic groups for centuries. Until the 20th century, there was a large proportion of Jews and Ukrainians in addition to a Polish majority. The initially small proportion of Ukrainians gradually increased due to an influx from the surrounding area. In addition, there were various minorities, such as German-speaking, due to the Austrian officials, or Armenian. At the beginning of the 21st century, the city is inhabited mainly by Ukrainians, but also by Russians, Belarusians and Poles. The Old Town is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site and is dominated by Renaissance, Baroque, Classicist and Art Nouveau buildings. Its Mediterranean flair served as a backdrop for Soviet films intended to portray Rome or Venice. Lviv was a venue of the 2012 European Football Championship.

_16.jpg)

Lviv (Lviv)

Coat of arms

Description: In blue a golden wall with three pewter towers, the highest in the center, and a running golden lion under the pointed archway.

History

See also: History of Ukraine, Galicia#History and History of Poland

Old Russian Lvov 1256-1349

In 1256 Daniel Romanovich of Galicia, the prince of the Kievan Rus principality of Galicia-Volhynia, built a castle for his son Lev on the site of today's Lviv. From this Lev (Old East Slavic for lion) the city got its name Lvov - "belonging to Lev or to the lion". The lion also appears in the coat of arms and in numerous stone sculptures of the city. The favorable location at the crossroads of trade routes allowed the city to grow rapidly. However, the ravages of Rus by the Mongols as well as tribute payments soon undermined the power of Galicia-Volhynia. After the local line of the Rurikid dynasty died out, Lvov fell first to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1340, then to Poland in 1349.

Polish Lwów 1349-1772

In 1356, the Polish King Casimir the Great granted Magdeburg city rights; German citizens, Jews as well as Roman Catholics settled in the city to a greater extent than before. In the same year, the Armenians received privileges from Casimir. The official language was now German for almost 200 years. The seal of the town council read in Latin S(igillum): CIVITATIS LEMBVRGENSIS. In 1387, after a short Hungarian rule, the town came back to the Kingdom of Poland. From 1375 to 1772, Lwów was the capital of the Polish Ruthenian Voivodeship and the Lvivian Land (Ziemia lwowska), since 1569 in the Noble Republic of Poland-Lithuania.

In the early modern period, the city developed into an important trading center and - along with Kraków, Vilnius and Warsaw - a center of Polish cultural and intellectual life. The near environs of Lwów became a Polish language island, but the area remained predominantly Ukrainian-speaking. In the 16th century, Lvov was home to the Russian Ivan Fedorov, one of the first East Slavic book printers after the Belarusian Francysk Skaryna.

During the Khmelnytskyi Uprising and the Russian-Polish War of 1654-1667, Lvov was besieged by the Zaporozhian Cossacks in 1648 and 1655. The city received the predicate semper fidelis ("always faithful") because it repeatedly defended itself against besiegers during the 17th century.

Founded in 1661 by the Polish King John II. Casimir, is the oldest university in Ukraine today.

Austrian Lviv 1772-1918

In 1772, with the first partition of Poland, the city fell to the Habsburg monarchy. Lviv became the capital of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria and the fourth largest city in the multiethnic state. Initially, Emperor Joseph II wanted to impose German as the language of administration, as he did throughout his dominions. From the time of Maria Theresa's school reform until about 1850, instruction in the secondary and trivial schools was exclusively in German, which was problematic because - as the Polish author Kazimierz Brodziński recalled - Polish children could only acquire the subject matter by memorizing it without understanding it.

In 1778 a German Evangelical Lutheran congregation was founded in Lviv. Its most active representative was the merchant Johann Friedrich Preschel.

In the middle of the 19th century, the composition of the civil service changed. While 600 of the 800 civil servants had previously been German, the relative autonomy of the Kingdom of Galicia from 1867 led to the rapid addition of Polish as a second language. Now mainly Poles functioned as officials of the Viennese k.k. Government in Galicia.

From 1867, when the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was formed, the Galicians had uniform Austrian citizenship and were represented in the Imperial Council, the parliament of Cisleithania in Vienna, by Polish and, after the extension of the electoral law, also by Ruthenian deputies. The Imperial Law Gazette published in Vienna was also published in Polish from 1867 and in Ruthenian from 1870.

Lviv was the seat of the k.k. Statthalter (the representative of the emperor and his government), the Sejm (regional parliament), three archbishops (Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, Armenian Catholic), who by virtue of their office were members of the Herrenhaus of the Austrian Imperial Council, and a chief rabbi. From 1804 to 1870 the city was also the seat of the Evangelical Superintendency A. B. Galicia. Consulates of Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia and Denmark were located in Lviv. The Galician capital had a university and a polytechnic, both with Polish language of instruction, four Polish, one German and one Ruthenian grammar schools.

Around 1900, about half of the inhabitants were Poles, a quarter Jews, and 30,000 Ruthenians (the term for Ukrainians at the time). The latter were discriminated against by the Polish population. In 1908, three Polish k.k. Gendarmes killed a Ruthenian peasant, after which the Ukrainian philosophy student Miroslaw Siczynski shot the governor, Count Andrzej Kazimierz Potocki. Bloody clashes between Polish and Ruthenian students followed.

Before World War I, Lviv was - with Krakow and Przemyśl Fortress - one of the largest garrisons of the Austro-Hungarian army in the east of the Empire. The location was a cornerstone for the protection of the Austro-Hungarian border against the Russian Empire. The Russian army captured Lviv at the end of August 1914 and advanced far to the west. Lviv remained occupied by Russia until June 1915 and was also threatened several times until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Polish Lwów 1918-1939

At the end of World War I, the West Ukrainian People's Republic was established in Lviv on November 1, 1918, but Poland gained control after sometimes fierce fighting in the Polish-Ukrainian War. Polish troops occupied the city on Nov. 21-22, 1918, and 64 people were killed in a pogrom against the Jewish population that lasted from Nov. 22-24, according to the report of Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Many were injured or robbed. It was proved that some of the Polish officers, soldiers and civilians were responsible. Also involved were members of the Jewish militia (a dozen were arrested) and deserters from the Galician army. Among the victims of the looting were also parts of the Polish and Ukrainian population. The act of violence permanently shook the previously quite harmonious coexistence of the various ethnic groups and religions in Lwów in the interwar period.

The city had 361,000 inhabitants at that time, most of them Poles (between 50 and 53 percent in 1912, over 55 percent from 1925), a third majority of Polonized Jews, and also Ukrainians, Germans and Polish Armenians. The majority of Ukrainians (about four to five-sixths of the population, depending on the district) lived in the area surrounding the city. In the interwar years, Lviv remained both a stronghold of Polish culture and a focal point of Ukrainian national feeling; however, the Habsburg supranational identity also remained present in the background. The Lviv-Warsaw School of Logic was world-renowned in the field of philosophy.

Administratively, as part of the Second Polish Republic, the city was the capital of the Lwów Voivodeship of the same name from 1921.

World War II

In September 1939, as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Lvov was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Republic by the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland in 1939 until 1941. The Polish army had offered fierce resistance to German troops despite artillery and air bombardment, as the area had been planned as a supply route for the Allies via Romania. This plan had not taken into account that Germany and the Soviet Union could have been Allied. Three days after the appearance of Soviet troops, the fighting stopped on September 22, 1939. The Germans left the city to the Soviet troops as agreed in the pact and withdrew. As everywhere in the Soviet Union, forced collectivization of economic associations and peasant farms now took place in Soviet-occupied Lvov. At that time, about 160,000 Poles, 150,000 Jews and 50,000 Ukrainians lived in the city.

Between the beginning of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 and the entry of the German Wehrmacht into Lvov, Soviet forces (mainly the NKVD) killed about 4000 political prisoners. In the early morning of June 30, 1941, the 1st Mountain Division under Major General Hubert Lanz and the Baulehrbataillon z. b. V. 800 "Die Brandenburger", supported by the Ukrainian volunteer battalion "Nachtigall", captured the city without resistance. That same day, members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Banderists (OUN-B) led by Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed the restoration of Ukrainian independence from the balcony of the Lubomirsky Palace. However, they were arrested by the Gestapo a few days later, as the German side did not want a Ukrainian state. Lvov became part of the German General Government and now functioned again under the name of Lviv as the capital of the district of Galicia.

The NKVD massacre of Ukrainian prisoners was exploited for propaganda purposes by the Wehrmacht units, the Nightingale Battalion and the Ukrainian nationalist and anti-Semitic OUN-B militia. This fueled a pogrom atmosphere directed against the Jewish civilian population. In mass killings on the first days of the German occupation, about 4,000 Jews died, some in "spontaneous" riots by Ukrainian militia and civilians in the city, but most in an organized mass execution by Einsatzgruppe C on the outskirts of the city on July 4, 1941. In addition, on the night of July 3 to 4, 1941, the Gestapo under then SS-Oberführer Karl Eberhard Schöngarth arrested 22 Polish professors, according to a list prepared with the help of Ukrainian students, and murdered them, in some cases also their relatives.

The district captain and thus supreme civil ruler in Lemberg was subsequently Joachim Freiherr von der Leyen from Krefeld. Almost all Jewish Lviv residents were subsequently murdered, including in the Lviv ghetto set up by the Nazis, in the municipal forced labor camp Lemberg-Janowska, and in the Belzec extermination camp. Almost all synagogues were destroyed. Only two buildings still exist today. In total, about 540,000 people were killed in concentration and prison camps in Lviv and its surroundings during the Nazi period, 400,000 of them Jews, including about 130,000 Lviv citizens. The remaining 140,000 victims were Russian prisoners.

As part of the German euthanasia policy, 2000 patients of the Kulparkow institution were murdered between 1941 and 1944. In addition, the Institute for Spotted Fever and Virus Research of the Army High Command was also located in Lviv.

Later in Lviv there was Prisoner of War Camp 275 for German prisoners of war of the Second World War. Near the camp there was a POW cemetery with over 800 graves. Those who were seriously ill were cared for in Prisoner of War Hospital 1241.

| Population composition in Lviv | ||||

| Ethnic group | 1900 | 1931 | 1959 | 2001 |

| Ukrainians | 19,9 | 15,9 | 60,0 | 88,1 |

| Russians | 000 | 00,2 | 27,0 | 08,9 |

| Jews | 26,5 | 31,9 | 06,0 | 00,3 |

| Poland | 49,4 | 50,4 | 04,0 | 00,9 |

Soviet Lvov 1945-1991

When the city came under Soviet rule again in the course of the Lviv-Sandomierz operation in 1944, most of the Poles living there were expelled. Part of the population was settled in Lower Silesia, especially in Wroclaw, after the Germans living there were expelled. Many Ukrainians who had previously lived in Polish western Galicia and central Poland were simultaneously forcibly resettled from Poland and settled by the USSR in or near Lvov. This fundamentally changed the ethnic and cultural composition of the city. The traditional Polish, Jewish and Armenian populations were replaced by Ukrainians.

The Soviet authorities began the reconstruction of the city, which was accompanied by the influx of skilled workers from all over the USSR and the industrialization of Lvov. By the 1980s, 137 large factories had been established, producing buses (LAZ), trucks, televisions, and machinery. The city population grew from 330,000 to 760,000. At the same time, nationalist currents among western Ukrainians were suppressed.

Ukrainian Lviv from 1991

Lviv has been part of independent Ukraine since 1991. Since then, autonomy aspirations have repeatedly emanated from Galicia, not least because of Lviv's history as the capital of its own kingdom. The city celebrated the 750th anniversary of its existence in the fall of 2006.

Rurikid Prince Daniel on the national monument Thousand Years of Russia

Remains of the Old Jewish Cemetery destroyed in 1948

.jpg)

Lviv ghetto, 1942

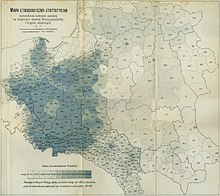

Ethnographic map of Poland by Edward Czyński and T. Tillinger (1912).

Lviv market square, c. 1787, before the dismantling of the city wall, Josephinische Landesaufnahme 1769-1787

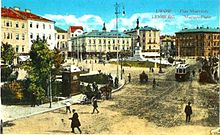

Marienplatz 1915

Jewish life

See also: History of Jews in Lviv

| Jews in Lviv | |||

| Year | Ges.-Bev. | Jews | Share |

| 1857 | 055.800 | 22.586 | 40,5 |

| 1880 | 110.000 | 30.961 | 28,2 |

| 1890 | 128.000 | 36.130 | 28,2 |

| 1900 | 160.500 | 44.258 | 27,6 |

| 1910 | 206.500 | 57.387 | 27,8 |

Since the Middle Ages Lviv was a center of Jewish life. The first documentary evidence of the existence of a Jewish community in Lviv dates back to the late 14th century. The oldest synagogue in the city was built in 1582. In the 19th century, about a third of the population were Jews. There were several Jewish cemeteries and numerous synagogues such as the Temple Synagogue, the Golden Rose Synagogue, the Great City Synagogue, and the Great Suburban Synagogue. Currently used synagogues are the Hasidic Synagogue and the Tsori Gilod Synagogue. From the 19th century there were two separate Jewish communities in Lviv: Conservative and liberal-minded Jews who lived separately, had little contact with each other, and each had their own rights, privileges, administrations, synagogues, and schools. The Jews of Lviv spoke Yiddish and German. Jewish philosophers and writers living in Lviv, such as Nachman Krochmal, Moritz Rappaport or Joseph Roth, wrote in German.

In 1908 Hasmonea Lwów was founded as the first Jewish sports club in Austria-Hungary. Well-known Jews living in the city included Rabbi Yehoshua Falk, Zionist Ruben Bierer, scholar Salomon Buber, historian Majer Balaban and soccer player Zygmunt Steuermann.

Politics

In the Lviv city and regional parliaments, the All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda," which was founded in Lviv, has held the most seats since the 2010 elections. The party is generally strong in Lviv oblast. The city's mayor since 2006 has been Andrij Sadovyj (Samopomich).

Economy

Lviv's economy is relatively diversified. Of particular importance is the IT industry, which employs around 12,000 workers. This means that around 15 percent of all Ukrainian IT professionals work in the city. Among the IT corporations based in Lviv is SoftServe, the largest Ukrainian IT company with about 4,000 employees. Another mainstay is tourism. Numerous new hotels and restaurants opened in the city, especially before the 2012 European Football Championship.

Landmarks

Old Town

Lviv's Old Town and the surrounding quarters built at the turn of the 20th century have an almost unique closed Renaissance, Baroque, Classicist, Historicist, Art Nouveau and Art Deco architecture that has been spared from wartime destruction and post-war interventions. In 1998, the historic center of the city was inscribed on the UNESCOWorld Heritage List. Reason: "With its urban structure and architecture, Lviv is an outstanding example of the fusion of architectural and artistic traditions of Eastern Europe with those of Italy and Germany. [...] Lviv's political and economic role attracted a number of ethnic groupings with different cultural and religious traditions that formed distinct yet interdependent communities within the city, which are still recognizable in the modern cityscape."

Sacral buildings

- Latin Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary (1360-1481)

- Greek Catholic Cathedral of Saint George (Bernard Meretyn, 1744-1770)

- Assumption Church of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (Paolo Romano, 1591-1629)

- Armenian Mary Cathedral (1356-1363)

- Church of All Saints (former Benedictine convent, 1597-1616)

- Former Stavropihija Church (Pavlo Rymlyanyn, 16th century)

- Boim Chapel (1609-1615)

- Former Dominican Church of Corpus Christi (Jan de Witte, 18th century)

- St. Andrew's Church (former Bernardine monastery, 17th c.)

- Beit Aaron We Israel Synagogue, 1924

Museums

- Open Air Museum Museum of Folk Architecture and Rural Life Shevchenko Grove

- National Museum in Lviv (Національний музей у Львові) with a large collection of icons.

- Kornjakt Palace with royal chambers (1580)

- Lviv Picture Gallery

- Lviv Museum of Religious History

- Ethnographic Museum (Museum of Folklore and Handicrafts)

- Bandinelli Palace ("Museum of Historical Treasures", 16th c.)

- Museum of the History of Western Ukraine (Black Palace, 1588/1589)

- Lviv Beer Museum (Brewery Museum)

- Weapons Museum of Ukraine in the former "Royal Arsenal of Lviv".

- Memorial Museum of the opera singer Salome Kruschelnytska

Other buildings and facilities

- Town hall on the market square (19th century)

- Town houses on the market square (Rynok, 16th-18th centuries)

- Lviv National Opera and Ballet Theater (19th century)

- Potocki Palace

- Lychakiwski Cemetery (historical-architectural monument)

- Janiwskyj Cemetery

- High Castle Hill: ruins of the castle of Prince Daniel Romanovich of Galicia

- Wall of the destroyed synagogue Golden Rose

- Strysky Park (1887)

- Biggest crossword puzzle in the world (January 2009)

Lviv marketplace

Galician Square is part of the ring road that surrounds the old town.

City Hall

Saint George Cathedral, in the 18th and 19th centuries the mother church of the Greek Catholic Church

Culture

Lviv has numerous theaters, museums and libraries, and the architecturally prominent Lviv National Opera in the city center. The largest Ukrainian book fair, the Lviv Book Forum, is held annually. The Alfa Jazz Fest or Leopolis Jazz Fest, held since 2007, has become a crowd puller.

On April 28, 2009, Lviv was chosen as the Ukrainian Capital of Culture for the year 2009. The competition was held for the first time in 2009.

Traffic

The city has a (small) international airport, which was expanded and modernized for the 2012 European Football Championships and has several weekly flights from Berlin, Munich, Dortmund, Düsseldorf, Athens, Prague, Istanbul and Vienna. The main railway station, built by the Imperial and Royal Austrian State Railways and opened in 1904, forms the center of rail traffic throughout western Ukraine and is served by passenger services from Moscow, Belgrade, Wroclaw, Kraków, Kiev, Kharkiv, Odessa, and Vienna, with no changes.

The city's public transport is provided by streetcars, trolleybuses and buses. This is supplemented by privately operated marshrutki (shared cabs). The city's streetcar network has been thoroughly renewed in recent years with financial support from the EBRD.

Reception building of the main station (built in 1903)

Education

Lviv has the following Ukrainian universities:

- National Ivan Franco University Lviv, founded in 1661

- National Polytechnic University of Lviv, founded in 1844

- Ukrainian Catholic University, founded in 1994

- National Medical Danylo Halyzkyj University Lviv, founded 1784

Sports

Motorsport

In the years 1930 to 1933, the automobile Grand Prix Lviv Grand Prix was held in the then Polish Lviv. The races were held in the streets Witoskoho, Hwardijiska and Stryjska.

In Lviv in the 21st century there is a significant speedway track with a well-known league racing club. Decisive qualifying rounds for the Speedway Individual World Championship have already been held here. Ukrainian speedway riders like Andriy Karpov, Oleksandr Loktaev, Igor Marko and Vladimir Trofimov learned speedway here.

Soccer

Between 1923 and 1939 the German club VIS Lwów existed in the city.

Lviv was one of the four Ukrainian venues for the 2012 European Football Championship in Poland and Ukraine. The Lviv Arena, built especially for this major event, hosted three Group B preliminary round matches.

In addition to Arena Lviv, there are two other major sports stadiums in Lviv, namely Stadium Ukrajina and SKA Stadium.

The most successful soccer team in the city is Karpaty Lviv. Furthermore, the city is home to FK Lwiw.

Twinning

Active partnerships

Lviv currently references seventeen sister cities:

| City | Country | Year |

| Banja Luka | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2004 |

| Wroclaw | Poland | 2003 |

| Budapest | Hungary | 1993 |

| Chengdu | China People's Republic | 2017 |

| Freiburg im Breisgau | Germany | 1989 |

| Krakow | Poland | 1995 |

| Kutaisi | Georgia | 2002 |

| Łódź | Poland | 2003 |

| Lublin | Poland | 2004 |

| Novi Sad | Serbia | 2005 |

| Plovdiv | Bulgaria | 2016 |

| Przemyśl | Poland | 1995 |

| Rochdale | United Kingdom | 1992 |

| Rzeszów | Poland | 1992 |

| Tbilisi | Georgia | 2013 |

| Vilnius | Lithuania | 2014 |

| Winnipeg | Canada | 1973 |

Inactive or unoccupied

- Corning (New York)

Corning, New York, since 1987

Corning, New York, since 1987 - Sweden

Eskilstuna, since 1994

Eskilstuna, since 1994 - Russia

Grozny, Chechnya, since 1998

Grozny, Chechnya, since 1998 - Israel

Rishon LeZion, Israel, since 1993

Rishon LeZion, Israel, since 1993 - Uzbekistan

Samarkand, Uzbekistan, since 2000

Samarkand, Uzbekistan, since 2000 - Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia, since 2006

Saint Petersburg, Russia, since 2006 - United Kingdom

Whitstable, United Kingdom

Whitstable, United Kingdom

Administrative subdivision

In addition to the city proper, which is divided into 6 city districts, the municipality also includes the town of Vynnyky (Винники) and the two settlements of urban type Bryukhovychi (Брюховичі) and Rudne (Рудне).

The city rajones are:

- Franko rayon (with the districts Na bajkach/На байках, Bohdaniwka/Богданівка, Kulparkiw/Кульпарків/Goldberghof, Kasteliwka/Кастелівка and Wulka/Вулька).

- Halytsch rayon (with the districts of Seredmistja/Середмістя, Zytadel/Цитадель, Sofijiwka/Софіївка and Snopkiw/Снопків)

- Lychakiv Rajon (with the districts of Lychakiv/Личаків/Lützenhof, Velyki Kryvchyki/Великі Кривчиці, Lysynychi/Лисиничі, Majorivka/Майорвка/Meier, Pohulyanka/Погулянка, Znesinnya/Знесіння, Kajserwald/Кайзервальд/Kaiserwald, Zetnerivka/Цетнерівка and Yaliwez/Ялівець).

- Salisnytsya rayon (with the districts of Ryazne/Рясне, Levandivka/Левандівка, Bilohorshcha/Білогорща, Klepariv/Клепарів/Klopperhof, Sknylivok/Скнилівок, Syhnivka/Сигнівка and Bohdanivka/Богданівка).

- Shevchenko rayon (with the districts of Holosko/Голоско, Samarstyniv/Замарстинів/Sommersteinhof, Sbojishcha/Збоїща, Ryazne/Рясне, Klepariv/Клепарів/Klopperhof, Hawrylivka/Гаврилівка or Pidsamche/Підзамче).

- Sykhiv Rajon (with the districts of Sykhiv/Сихів, Passiky/Пасіки, Pyrohiwka/Пирогівка, Koselnyky/Козельники, Bodnariwka/Боднарівка, Novy Lviv/Новий Львів, Persenkivka/Персенківка and Snopkiw/Снопків).

Personalities

→ Main article: List of personalities of the city of Lviv

Climate table

| Lviv | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Lviv

Source: wetterkontor.de, reference period from 1961 to 1990 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of Archbishops of Lviv of the Roman Catholic Church

- List of Metropolitans of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- Lviv flight day accident

- Battle of Lviv

Search within the encyclopedia