Ludlow Castle

Ludlow Castle is a ruined medieval fortress in Ludlow in the English county of Shropshire. It stands on a headland above the River Teme. The castle was probably built by Walter de Lucy after the Norman Conquest of England as one of the first stone castles in England. During the civil war of the 12th century, the castle passed through various hands of the Lucy family and rival clans, and was further strengthened with a donjon and a large outer bailey. In the mid-13th century Ludlow Castle passed to Geoffrey de Geneville, who had parts of the core castle rebuilt. The castle played an important role in the Second War of the Barons. Roger Mortimer acquired the castle in 1301 and had the core castle further extended and his family held Ludlow Castle for over a century.

Richard, the Duke of York, inherited the castle in 1425 and so it became an important symbol of the power of the House of York in the Wars of the Roses. When Richard's son, Edward IV, ascended the throne in 1461, the castle became the property of the Crown. Ludlow Castle was designated as the seat of the Council in the Marches of Wales, effectively making it the capital of Wales, and was extensively renovated throughout the 16th century. By the early 17th century the castle was almost luxuriously appointed and cultural events, such as the first performance of John Milton's masque Comus, were held there. During the English Civil War of the 1640s, Ludlow Castle was held by the Royalists until it was besieged and captured by the Roundheads in 1646. The castle's interior was sold and it served as a garrison for most of the Interregnum.

With the Stuart Restoration in 1660, the Council was also reinstated and the castle repaired, but Ludlow Castle never recovered from the Civil War years and when the Council was finally abolished in 1689, the castle fell into neglect. Henry Herbert, the Earl of Powis leased the castle from the Crown in 1772 and had the ruins beautifully restored. His brother-in-law, Edward Clive even bought the castle in 1811. A manor house was built in the outer bailey, but the rest of the castle remained largely untouched, attracting an increasing number of visitors and becoming a popular place for artists. After 1900 Ludlow Castle was cleared of rampant scrub and extensively repaired by the Powis estate and government departments during the 20th century. Today, in the 21st century, it is still owned by the Earl of Powis and serves as a tourist attraction.

The architecture of Ludlow Castle reflects the long history of the castle with its different architectural styles. The castle has an area of about 152 × 133 meters, which is almost 2 hectares. In the outer bailey you will find Castle House, now used by the estate administration, while in the core castle, separated from the outer bailey by a moat cut into the stone, you will find the donjon, a solar block (drawing room for the family), a block for knights' hall and parade bedroom, as well as 16th-century fixtures and a rare circular chapel over a holy tomb. English Heritage notes that the castle ruins represent a "remarkably complete complex of different ages" and considers Ludlow Castle to be "one of England's finest castle complexes".

Ludlow Castle from the southeast

History

11th century

Ludlow Castle is believed to have been built at the instigation of Walter de Lucy around 1075. Walter Lucy arrived in England as a member of William FitzOsbern's household at the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. FitzOsbern was made Earl of Hereford and entrusted with the settlement of the area. At the same time quite a few castles were founded in the west of the county to secure the border with Wales. Walter de Lacy was the Earl's vice and was granted 163 manors spread over seven counties, 91 of which were in Herefordshire alone.

Walter de Lacy ordered the construction of a castle to begin in the manor of Stanton Lacy; the fortress was originally called Dinham Castle and was then renamed Ludlow Castle. Ludlow Castle was Walter de Lacy's most important castle. It was situated in the centre of his new lands and at an important road junction above the Teme River on an easily defended rocky outcrop. Walter de Lacy died in a building accident at Hereford in 1085. He was succeeded by his son, Roger de Lacy.

The Norman stone fortifications were probably added to the castle in the 1080s and their construction was completed before 1115. They were located around the present core castle and formed a stone version of a ringwork. They consisted of four towers, a gatehouse tower, and castle walls with a moat cut out of the rock along two sides. The rubble stone thus removed was used to build the houses in the castle, making Ludlow Castle one of the very first masonry castles in England. With its circular layout and grand gatehouse tower, it was in keeping with earlier Anglo-Saxon burh constructions. In 1096 Roger de Lacy lost all his lands after rebelling against William II. They passed to Roger's brother, Hugh de Lacy.

12th century

Hugh de Lacy died childless about 1115 and Henry I gave Ludlow Castle and most of the surrounding lands in fief to Hugh's niece Sybil and married her to Pain FitzJohn, one of his household servants. Pain FitzJohn used Ludlow Castle as the baronial seat and headquarters of his lands. These surrounding lands and Knight's fees in turn supported the castle and its defences. Pain FitzJohn died fighting the Welsh in 1137, causing a struggle for the inheritance to the castle. Roger Fitzmiles, who wanted to marry Pain FitzJohn's daughter, claimed the castle, as did Roger de Lacy's son Gilbert. At the time Stephen had just ascended the English throne, but his position was still uncertain and he therefore gave the castle in 1137 in fief to Roger FitzMiles, who promised him political support in return.

Anarchy soon broke out, a civil war between Stephen and Empress Matilda, and Gilbert de Lacy took the opportunity to rise against Stephen and take Ludlow Castle. Stephen responded by sending an army into the Welsh Marches, where he gained additional support by marrying Sybil to one of his knights, Josce de Dinan, and promising future ownership of Ludlow Castle to them. Stephen's forces captured the castle after quite a few attempts in 1139, Stephen rescuing his ally, Prince Henry of Scotland, when he became entangled in a hook thrown over the castle walls by the garrison. Gilbert de Lacy, however, still insisted that he was the rightful owner of Ludlow Castle, and so a private war broke out between him and Josce de Dinan. Gilbert de Lacy was eventually successful and so captured the castle a few years before the end of the civil war in 1153, but ultimately he moved to the Levant, leaving the castle first in the hands of his eldest son, Robert, and then, after Robert's death, in those of Robert's younger brother Hugh de Lacy.

At this time the Great Tower, a kind of donjon, was built from the gatehouse tower, either during the siege of 1139 or at the time of the private war between Gilbert de Lacy and Josce de Dinan. The old Norman castle had also become too small for the growing household, and so, probably between 1140 and 1177, an outer bailey was added to the south and east of the original castle, creating a large open square. This moved the entrance to the castle from the south to the east, opposite the growing town of Ludlow. Gilbert de Lacy probably had the circular chapel built inside the core castle because it resembled the churches of the Knights Templar, which he later joined.

Hugh de Lacy took part in the Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland and was elevated to Lord of Meath in 1172. He spent much time away from Ludlow Castle and King Henry II confiscated the castle in his absence, possibly to ensure his loyalty in Ireland. Hugh de Lacy died in Ireland in 1186 and the castle passed to his son Walter, who was still an infant and did not take possession of the estate until 1194. During John Ohneland's rebellion against Richard I in 1194, Walter de Lacy joined the attacks against Prince John. Richard I, however, took no notice and confiscated Ludlow Castle and Walter's other possessions. Walter de Lacy offered to buy back his lands for 1000 marks, but his offer was rejected until finally in 1198 they agreed on the huge sum of 3100 marks.

13th century

Walter de Lacy travelled to Ireland in 1201 and the following year his estates, including Ludlow Castle, were again confiscated to ensure his loyalty and placed under the control of his father-in-law, William de Braorse. He regained his lands for a penalty of 400 marks, but in 1207 his disagreements with the royal officials in Ireland led John Ohneland to retake the castle and transfer control to William de Braorse. Walter de Lacy reconciled with John Ohneland again in 1208, but in the meantime William de Braorse himself had fallen out of favour; fighting broke out and both de Lacy and de Braorse fled to Ireland while John Ohneland once again took control of the castle. It was not until 1215 that the disagreements were resolved and John Ohneland agreed that Ludlow Castle would be returned to Walter de Lacy. At some point in the early 13th century the innermost ring of walls was added to the castle, creating a separate private sphere for the lordship within the core castle.

In 1223, the English King Henry III met with the Welsh Prince Llewelyn ab Iorwerth at Ludlow Castle for peace talks, but the negotiations were unsuccessful. In the same year doubts about Walter de Lacy's activities in Ireland beset King Henry and so, among other measures to secure his loyalty, the Crown took over Ludlow Castle for two years. In May 1225 Walter de Lacy got the castle back when he carried out an attack on Henry's enemies in Ireland and paid the king 3000 marks for the return of the castle and his lands. By the 1230s, however, Walter de Lacy had accumulated £1000 debts to Henry and other, private creditors which he was unable to repay. He therefore signed Ludlow Castle over to the king as security for his loan in 1238, but he must have got the fortress back sometime before his death in 1241.

Walter de Lacy's granddaughters, Maud and Margaret were to inherit their grandfather's remaining lands on his death, but they were still unmarried at the time, making it difficult for them to hold landed property themselves. King Henry informally divided the lands between them, with Ludlow Castle falling to Maud. He married her off to a royal favourite, Peter de Geneva, and at the same time cancelled much of the debt she had inherited from her grandfather. Peter de Geneva died in 1249 and Maud married a second time, this time to Geoffrey de Geneville, a friend of Prince Edward, the future king. In 1260, King Henry officially divided Walter de Lacy's lands, allowing Geoffrey de Geneville to keep the castle.

King Henry lost his power in the 1260s, resulting in the Second War of the Barons throughout England. After the defeat of the royalists in 1264, the leader of the rebels, Simon de Montfort, captured Ludlow Castle, but it was retaken a short time later by supporters of Henry, probably led by Geoffrey de Geneville. Prince Edward escaped from captivity in 1265 and met with his supporters at the castle before beginning his struggle to regain the English throne, which culminated in Montfort's defeat at the Battle of Evesham later that year. Geoffrey de Geneville held the castle throughout the rest of Edward I's century and reign, prospering until his death in 1314. De Geneville had the knight's hall and solar built during this period, either between 1250 and 1280 or later in the 1280s or 1290s. Construction of Ludlow's town walls also began in the 13th century, probably from 1260. This wall was connected to the castle and together with it formed a closed defensive ring around the town.

14th century

Geoffrey and Maud's eldest granddaughter, Joan, married Roger Mortimer in 1301, bringing the Mortimers into possession of Ludlow Castle. Around 1320 Roger Mortimer had the parade bedroom block added to the knight's hall and the solar in the style then common in three-part dwellings in castles. He had another building built on the site where the Tudor dwellings were later erected, as well as a toilet tower on the curtilage. Between 1321 and 1322 Mortimer found himself on the losing side of the Despenser War. After his imprisonment by King Edward II, he escaped from the Tower of London into exile in 1323.

While in France, Mortimer formed an alliance with Isabelle, King Edward's estranged wife, and together they gained power over England in 1327. Mortimer was made Earl of March and became very wealthy. He probably entertained Edward III in his castle in 1329, and the Earl had a new chapel built in the outer bailey, dedicated to St Peter because Mortimer had managed to escape from the Tower on his feast day. Mortimer's work at Ludlow Castle was presumably intended to create, as historian David Whitehead put it, a 'show castle' with chivalric and Arthurian undertones, reflecting the already archaic Norman architectural style of the time. Mortimer lost his power the following year, but his widow Joan was allowed to keep Ludlow Castle.

Ludlow Castle slowly moulted into the Mortimer family's most important property, but in the remaining years of the 14th century the respective owners were too young to control the castle personally. The castle was inherited briefly by Mortimer's son Edmund, but then in 1331 by Mortimer's youngest grandson Roger, who later became a prominent combatant in the Hundred Years War. Roger's younger son Edmund inherited the castle in 1358, grew up there and also fought in the war against France. Both Roger and Edmund took advantage of a legal provision called "The Use" which effectively granted Ludlow Castle to trustees in return for annual payments throughout their lives. This reduced their tax payments and gave them more control over the granting of their lands on their respective deaths. Edmund's son, another Roger, inherited the castle in 1381, but King Richard II used Roger's youthful age to take advantage of the Mortimers' lands until they were placed under the control of a committee of important nobles. When Roger Mortimer died in 1398, King Richard again took guardianship of the castle for young Edmund until he was deposed as king in 1399.

15th century

Ludlow Castle was under the guardianship of King Henry IV when the Owain-Glyndŵr revolt broke out across Wales. Officers were detached to the castle to protect it from the rebel threat, first John Lovel and then Henry's half-brother, Sir Thomas Beaufort. Roger Mortimer's younger brother, Edmund, moved an army from the castle against the rebels in 1402, but was captured at the Battle of Bryn Glas. Henry refused to ransom him, and later married one of Glyndŵr's daughters before dying at the siege of Harlech Castle in 1409.

Henry placed the young heir to Ludlow Castle, another Edmund Mortimer, under house arrest in the south of England and kept a firm grip on the castle himself. This situation continued until Henry V finally returned Edmund's lands in 1413, with Edmund continuing to serve the Crown overseas. As a result, the Mortimers rarely visited their castle during the first half of the 15th century, despite the fact that the surrounding town had grown rich in the wool and cloth trade. Edmund accumulated large debts and was forced to sell the rights to his Welsh estates to a consortium of nobles before dying childless in 1425.

The castle was inherited by Edmund's sister's youngest son, Richard, Duke of York, who took possession of it in 1432. Richard took a keen interest in the castle, making it the administrative centre of his lands in the area and living there probably by the late 1440s, but certainly by the 1450s. Richard also brought his sons, including the later Edward IV, and their households to the castle. He was probably responsible for the rebuilding of the northern part of the great tower at this time.

In the 1450s the Wars of the Roses broke out between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, to which Richard belonged. For most of the conflict Ludlow Castle was not on the front line, but served as a safe retreat from the main fighting. An exception to this was the Battle of Ludlow, which took place just outside the town gates in 1459 and ended in a largely bloodless victory for Henry VI of the House of Lancaster. After the battle, ''Edmund de la Mare'' was appointed constable of the castle to break Richard's hold on the region. John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, was given further rule. Richard fell in battle in 1460 and his son Edward came to the throne of England the following year, regaining control of Ludlow Castle and reuniting it with the Crown estates.

The new king, Edward IV, visited the castle regularly and established an assembly there to rule over his lands in Wales. He had only a limited amount of work carried out on the estate, although he was probably responsible for the rebuilding of the great tower. In 1473 Edward IV, possibly influenced by his own childhood experiences, arranged for his eldest son, the future Edward V, and his brother, Prince Richard, to live at the castle. It also became the seat of the newly formed Council of Wales and the Marches. From this point onwards Ludlow Castle served mainly as a residence rather than a military establishment, but was still rich in chivalric significance and a valuable symbol of Yorkist power and their claim to the throne. Edward IV died in 1483, but after Henry VII took the throne in 1485 he continued to use Ludlow Castle as a regional base, giving it in fief to his son, Prince Arthur, in 1493 and re-establishing the dormant Council of Wales and the Marches there.

16th century

In 1501 Prince Arthur Ludlow Castle arrived on his honeymoon with his bride Catherine of Aragon before he died the following year. The Council of Wales and the Marches continued to function, but under the leadership of its president, Bishop William Smyth. The Council continued to develop into a combination governmental body and court. It adjudicated a number of conflicts throughout Wales and maintained law and order, making Ludlow Castle virtually the capital of Wales.

Mary Tudor, daughter of Catherine of Aragon, and Henry VIII, with their entourage of servants, advisers and protectors, spent 19 months at Ludlow Castle, where they oversaw the Council of Wales and the Marches from 1525 to 1528. The relatively small sum of £5 was spent on renovating the castle before their arrival. The Council's wide-ranging role was further strengthened by the legislation of 1534 and its purpose further emphasised in the Act of Union of 1543. Some of its presidents, such as Bishop Rowland Lee, used its wider powers more widely to sentence local criminals to death, but later presidents tended to favour sentencing to pillory, flogging or imprisonment in the castle. The castle's Parade Bedroom served as the Council's meeting room.

The installation of the Council of Wales and the Marches at Ludlow Castle gave it a new use at a time when many similar fortresses were falling into increasing disrepair. By the 1530s the castle was in desperate need of renovation. Lee had work begun in 1534, for which he borrowed money, but Sir Thomas Engleford complained the following year that the castle was still not fit for residential use. Lee had the roofs of the castle repaired, presumably using lead sheeting from the Carmelite Friary in the city. The money came from fines imposed by the Council and from confiscated goods. He later stated that the work on the castle would have cost about £500 if the Crown had had to pay for it directly. The porter's lodge and the prison in the outer bailey were built about 1552. The woods around the castle were gradually cut down in the 16th century.

Elizabeth I, under the influence of her favourite Robert Dudley, appointed Sir Henry Sidney as President of the Council in 1560 and he moved to Ludlow Castle. Sidney was a keen antiquarian with an interest in chivalry and used his tenure to restore most of the castle in the Perpendicular Style. He had the castle extended by adding living quarters for the family between the Knight's Hall and Mortimer's Tower. He used the former royal living quarters as guest rooms and began the tradition of decorating the Knights Hall with the coats of arms of officers of the Council. The larger windows of the castle were glazed and a clock and plumbing installed. Judicial facilities were improved with a new court house created from the 14th century chapel, and facilities for prisoners and for the storage of court records were created in Mortimers Tower. The restoration met with general approval and, although it also included a fountain, a jeu-de-paume field, ambulatories and a viewing platform, was less ephemeral than other castle restorations of the time.

17th century

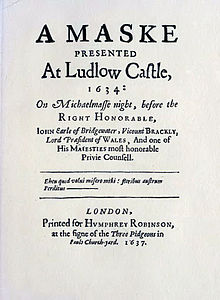

In the 17th century the castle was luxuriously furnished and given an expensive but also grand household around the Council of the Marches. The future King Charles I was proclaimed Prince of Wales by King James I at the castle in 1616 and Lodlow Castle was made his headquarters in Wales. A troupe called the Queen's Players entertained the Council in the 1610s and in 1634 John Milton's masque Comus was first performed in the Knights' Hall for John Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater. The Council, however, came under increasing criticism for its legal practices and in 1641 an Act of Parliament stripped it of all legal powers.

When the English Civil War broke out in 1642 between the supporters of King Charles and those of Parliament, Ludlow and the surrounding area supported the Royalists. A royalist garrison was raised in the town under the command of Sir Michael Woodhouse and the fortifications of the castle were strengthened. Artillery was transferred to the castle from nearby Bringwood Forge. When the fortunes of war turned against the king in 1644, the garrison was withdrawn to reinforce troops in the field. The military situation of the king's retainers continued to deteriorate and in 1645 the remaining outlying garrisons were called in to defend Ludlow itself. In April 1646 Sir William Brereton and John Birch led an army of Parliamentarians from Hereford to take Ludlow. After a brief siege, Woodhouse surrendered the castle and town on good terms on 26 May 1646. The castle was initially garrisoned, but in 1653 most of the arms were removed from the castle for security reasons and sent to Hereford. In 1655 the garrison was completely disbanded. In 1659, political instability in the government led to Ludlow Castle being garrisoned again with a garrison of 100 men led by William Botterell.

Charles II returned to the English throne in 1660 and re-established the Council of the Marches in 1661, but the castle was never to recover from the Civil War. Richard Vaughan, 2nd Earl of Carbery, was appointed President of the Council and given £2000 to renovate the castle. In 1663-1665 a garrison of infantry soldiers was stationed at Ludlow Castle under the Earl's supervision. Their job was to guard the castle's money and furnishings, as well as ammunition for the local Welsh militia. The Council of the Marches was unable to re-establish itself and was finally abolished for good in 1689, ending Ludlow Castle's role in the government of England. The castle was no longer needed. As a result, the buildings were neglected and quickly fell into disrepair.

18th century

The castle remained in a dilapidated state and in 1704 the then governor William Gower proposed to demolish it and build a contemporary style residential enclosure in its place. His suggestion was not followed, but by 1708 only three rooms were still in use in the hall block. Many of the other buildings in the core castle were no longer usable and most of the remaining furniture was rotten or broken. Soon after 1714 the lead sheets were removed from the roofs and the wooden ceilings gradually collapsed. The writer Daniel Defoe visited the castle in 1722 and noted that the castle was "in a state of perfect decay". Nevertheless, some rooms remained usable for many years, possibly as late as the 1760s and 1770s. Drawings of the gate block to the core castle from this period show it still intact and visitors noted that the circular chapel was still in good condition. The stonework was overgrown by ivy, trees and scrub and by 1800 the Chapel of St Mary Magdalene was finally in ruins.

Alexander Stuart, a captain in the army, the last governor of the castle, had what remained of the fortifications demolished in the mid-1700s. Some of the stones were used to build Bowling Green House - later renamed Castle Inn - at the northern end of Jeu-de-Paume Square, while the outer bailey was made into Bowling Green. Stuart lived in a house in the town of Ludlow, but decorated the castle's Knight's Hall with the remains of the Arsenal and probably charged visitors an entrance fee.

It became fashionable at the time to restore castles as private residences and the later King George II probably considered making Ludlow Castle habitable again but was put off by the estimated cost of £30,000. Henry Herbert, the Earl of Powis, later took an interest in the ruined castle and approached the Crown in 1771 asking to be allowed to lease it. It is unclear whether he wanted to continue to extract building materials from the castle or, more likely, turn it into a private residence. But the castle was already "extremely ruinous" according to Powis's surveyor's report from the end of the same year, the walls "mostly rubble and the battlements mostly derelict". The Crown offered a lease for 31 years at a rent of £20 a year, which Lord Powis accepted in 1772, only to die shortly afterwards.

Henry's son, George Herbert, took over the lease and his wife Henrietta had public gravelled paths laid through the rocks around the castle and trees planted throughout the estate to improve the appearance of the castle. The walls and towers of the castle were superficially repaired and cleaned, usually when parts of them were in danger of collapsing. The courtyard of the core castle was levelled, at considerable cost. The landscape park also needed expensive maintenance and repair.

The town of Ludlow became increasingly modern and visited by tourists, with the castle being a particularly popular attraction. Thomas Warton published an edition of Milton's poems in 1785, describing Ludlow Castle and publicising its association with Comus, which reinforced the castle's reputation as a picturesque and sublime place. The castle became a subject for painters interested in these subjects: William Turner, Francis Towne, Thomas Hearne (1744-1817), Julius Ibbetson, Peter de Wint and William Marlowe all produced illustrations of the castle in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, often taking artistic license in details to achieve a romantic atmosphere.

19th century

Edward Clive, George's brother-in-law and heir, attempted to obtain a lease for the castle from 1803, pointing to his family's efforts in restoring the castle. In his efforts to continue the lease, he faced competition from the government's barracks department, which wanted to use the castle as a prisoner of war camp for over 4000 French soldiers from the Napoleonic wars. After considerable discussion, the plan for a prisoner of war camp was eventually dropped and Lord Clive, who by then had been elevated to Earl of Powis, was offered the opportunity to buy the castle for £1560. In 1811 he took up this offer.

Between 1820 and 1828 the Earl had the abandoned Jeu-de-Paume Square and Castle Inn - which he closed in 1812 after buying the castle - converted into a new, large building called Castle House, which stands above the north side of the outer bailey. From the 1840s this house was leased, first to George Hodges and his family, then to William Urwick and Robert Marston, all important members of the local landowning class. This mansion contained a drawing room, dining room, study, quarters for servants, a greenhouse and vines. In 1887 the annual rent was £50.

In the 19th century the castle walls were again overgrown with vegetation, although attempts were made to control the plants and quite a few walls were cleared of them following a report by Arthur Blomfield in 1883 which showed the damage caused by the ivy. Ludlow Castle was held in high esteem by Victorian antiquarians; George Clark called it "the glory of the middle Marches of Wales" and remarked that its setting amidst sparse woodland made it "probably without equal in Britain". When the town of Ludlow was connected to the growing railway network in 1852, the number of tourists to the castle increased. Admission at that time cost sixpence. The castle was used for many purposes. Sheep and goats were grazed on the grassy areas of the outer bailey and they were used for par force hunts, sporting events and agricultural shows. Parts of the outer bailey were used for timber storage and at the turn of the century the local volunteer militia used the old prison as an ammunition store.

20th century

W. H. St. John Hope and Harold Brakspear began a series of archaeological investigations at Ludlow Castle in 1903. They published their findings in 1909 and they are still valued by modern academics. Christian Herbert, the Earl of Powis, had most of the castle's stonework cleared of ivy and other overgrowth. In 1915 the castle was declared an Ancient Monument by the state, but continued to be owned and maintained by the Earl and the Trustees of the Powis lands.

The castle was increasingly resolutely maintained and in the 1910s and 1920s the large trees on the estate were felled and the animals evicted from the core and outer bailey on the grounds that they posed a health and injury risk to visitors. In the 1930s the remaining vegetation was removed from the castle walls, the cellars were cleared by the government Office of Works and the stable block was converted into a museum. Tourists continued to visit the castle; in the 1920s and 1930s many groups of workers came from the new car factories in the area. The open spaces in the castle were used by the townspeople for football tournaments and similar events; in 1934 Milton's Comus was again staged in the castle to mark the 300th anniversary of its first performance.

Castle House in the outer bailey was leased to the diplomat Sir Alexander Stephen in 1901; he had extensive work carried out on the house in 1904, extending and modernising the north side of the house, for example by adding a billiard room and library. The cost was estimated at around £800. Castle House continued to be leased by the Powis estate to wealthy individuals until the Second World War. One of these tenants, Richard Henderson, stated that he had spent about £4000 on maintaining and extending the house; the rental value of the property increased from £76 to £150 during this period.

During World War II, the castle was used by the Allied military. The Great Tower served as a lookout and US forces played baseball in the castle gardens. Castle House stood empty after the death of the last tenant, James Geenway. In 1942 it was briefly requisitioned by the Royal Air Force and converted into housing for wartime workers. This caused considerable damage, later estimated at £2000. In 1956 Castle House was returned to the Earl of Powis, who sold it the following year to Ludlow Town Council for £4000. The latter then rented out the flats.

Then, in the 1970s and early 1980s, the Ministry of the Environment supported the Powis estate management by loaning state employees to repair the castle. However, visitor numbers declined, partly because of the neglected state of the estate, and so the estate management became less able to maintain the castle adequately. In 1984 English Heritage took over from the Environment Agency and the task of maintaining the castle was approached more systematically. This was based on a partnership which left ownership of the castle with the estate management, who opened the castle to visitors in return for £500,000 from English Heritage for a jointly funded repair and maintenance programme. Repairs and maintenance were carried out by specialist contractors. This included repairs to parts of the curtain wall which collapsed in 1990 and a new visitor centre. Limited excavations were carried out in the outer bailey by Hereford City Council's Archaeology Department from 1992 to 1993.

21st century

Today, in the 21st century, Ludlow Castle is owned by John Herbert, the current Earl of Powis, but is run by the Trustees of the Manor as a tourist attraction. In 2005 over 100,000 tourists visited the castle, more than in previous decades. As part of the annual Ludlow Festival, a Shakespeare performance is traditionally held at the castle. It is also the centre of the Ludlow Food and Drink Festival each September.

English Heritage considers Ludlow Castle to be "one of England's finest castles". The ruins represent a "remarkably complete complex from different periods". They are listed as a Scheduled Monument and Historic Building I. Grade listed. By the early 21st century Castle House had become quite derelict and English Heritage placed it on the 'At-Risk Register'. In 2002 the estate bought this building back from South Shropshire District Council for £500,000, refurbished it and converted it into offices and rented accommodation and it reopened in 2005.

Ludlow Food and Drink Festival 2003 in the castle courtyard

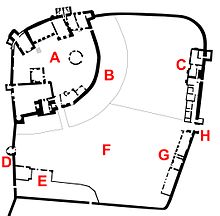

Layout of Ludlow Castle: A - Core Castle; B - Moat; C - Castle House; D - Mortimers Tower; E - Chapel of St. Peter; F - Forecastle; G - Keepers House, Prison and Stables; H - Entrance

The core castle and visitors 1852

Painting of the castle in October 1812 after landscaping and extensive tree planting, by an unknown artist.

18th century illustration of Ludlow Castle by Samuel Scott. The painting was made between 1765 and 1769 before landscaping on the estate.

Title page of John Milton's Comus, first performed at Ludlow Castle in 1634.

Interior of the Judges' Lodgings with the spiral staircase (centre)

Medieval tile, probably from Ludlow Castle, originally part of a hunting scene.

.jpg)

The interior of the Parade bedroom block

The 14th century Parade Bedroom Block and the 12th century St. Mary Magdalene Chapel.

Solar from the 13th century (left) and Knights' Hall (right) in front of the north-west tower

Ludlow Castle, built on a rocky headland, seen here across the River Teme.

The Great Tower built in the mid-12th century (centre) and the entrance to the late-12th century core castle (right).

Architecture

Ludlow Castle is built on a rocky outcrop above the modern town of Ludlow to the east. The site slopes steeply about 30 metres south and west to the River Corve and River Teme. The castle complex is roughly rectangular in shape and measures about 150m × 130m. It covers an area of 2 hectares in total. The interior of the castle complex is divided into two main parts: a core castle in the northwest corner and a much larger outer castle. A third part, called the innermost castle, was created in the early 13th century by building walls in the southwest corner of the core castle. The castle walls connect to the south and east sides of the medieval walled ring of Ludlow. The castle is constructed from a range of different building stones: Norman-period masonry is of grey-green siltstone rubble, with workstones and cornerstones of red sandstone. Later masonry consists exclusively of the red sandstone of the area.

Vorburg

The outer bailey is entered through the gatehouse. The space within the curtain wall is divided into two parts. On the north side of the outer bailey is Castle House and its gardens. The house is two storeys high and was built on the old walls of the Jeu-de-Paume square and the Castle Inn. The north side of Castle House abuts the Beacon Tower, which overlooks the city.

In the other half of the outer bailey are the guardroom, the prison and the block of stables that runs along the east side. The guardroom and prison consist of two buildings, 12 m × 7 m and 17.7 m × 7 m, both two-storey and built of ashlar. The stables are at the far end, are built in rubble stone and are 20.1 m × 6.4 m in size. The outer walls of the prison were originally decorated with the coats of arms of Henry, Earl of Pembroke, and Queen Elizabeth I, but these have been destroyed, as have the barred windows which once protected the house.

Along the south side of the outer bailey are the remains of St Peter's, a 14th-century chapel, about 6.4 m × 15.8 m in size, which was later converted into a courthouse and provided with an extension reaching to the western curtine. The courtroom extended over the whole of the first floor, and court records were stored in the rooms below. The southwest corner of the outer bailey is separated from the rest of the outer bailey by a modern wall.

The western curtain wall is about 1.96m thick and supports the 13th-century Mortimers Tower, which measures 5.5m × 5.5m externally and houses a vaulted chamber on the ground floor with a 3.7m × 3.7m floor area. Initially Mortimer's Tower was built as a three-storey gatehouse in an unusual D-shaped plan, possibly similar to that at Trim Castle in Ireland. But in the 15th century the entrance was closed off, turning the tower into an ordinary masonry tower, and in the 16th century an additional storey was added. The tower has no roof today; however, it did not lose it until the late 19th century.

Core castle

The core castle shows the extension of the original Norman castle and is enclosed by a 1.5-1.8 m thick curtain wall. On the south and west sides, the wall is additionally protected by a moat, which was cut out of the rock up to 24 m deep. It is spanned by a bridge, which still consists of a part of the stones of its predecessor from the 16th century. In the core castle, another courtyard in the southwest corner, called the innermost castle, was divided off by a 1.5 m thick stone wall in the 13th century.

The gatehouse to the core castle bears the coats of arms of Sir Henry Sidney and Queen Elizabeth I above it, dating from 1581. It was originally a three-storey building with skylights and open fireplaces, and probably served as a dwelling for the justices. There were probably also shield holders under the coats of arms, but these have been lost in the course of time. There was a guardroom to the right of the entrance, from where access could be controlled. The rooms were accessed by a spiral staircase in a projecting tower. The building had prominent triple chimneys. All of these rooms no longer exist today. Along the gatehouse was originally a half-wooden building, possibly a laundry, 14.6 m × 4.6 m in size. This building also no longer exists today.

On the east side of the core castle is the 12th century Chapel of St Mary Magdalene. The circular Romanesque construction of the chapel is unusual; there are only three other examples of it in England, at Castle Rising Castle, at Hereford Castle and at Pevensey Castle. Built of sandstone, the circular building is said to be reminiscent of the shrine in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Originally the chapel had a nave and a square, 3.8m × 3.8m chancel, but this structure was substantially altered in the 16th century and only the nave survives today. The nave also has no roof today. It has a diameter of 8 m and is visibly divided into two sections by various strips of masonry. Some plaster has also survived in the lower sections. There are 14 niches on the interior walls of the nave.

The north side of the core castle is occupied by various buildings, the Solar Block, the Knights' Hall and the Parade Bedroom Block. The Tudor chambers are located in the northeast corner. The latter are in the form of two rhomboids, so as to fit into the angle formed by the curtine. They are separated by a wall; the west side is about 10.1m × 4.6m, the east side 10.1m × 6.4m. They were accessible by a common spiral staircase, a construction found in many 16th-century bishop's palaces. Originally there was a series of small offices and private rooms for the clerks of the court, which were later converted into two separate apartments.

The parade bedroom block, which adjoins the Tudors' chambers, was created around 1320. It was also created as a rhomboid, about 16 m × 10 m in size. The master bedroom was originally on the upper floor, but was substantially altered in later years. The hewn brackets that survive on the upper floor today possibly depict Edward II and Queen Isabella. Behind the parade bedroom block is the abortuary tower, a four-storey structure containing a combination of chambers and abortuaries.

The 13th century knights' hall was also located on the 1st floor. It originally had a wooden floor supported by stone pillars on the ground floor and a massive wooden roof. It measured 18.3 m × 9.1 m; the length-to-width ratio of 2 : 1 was typical of knights' halls of this period. The knights' hall could be reached by a set of stone steps on the west side. It was lit by three tall, tripartite windows, each with its own window seat and facing south to let in the sunlight. Originally the Knight's Hall had an open fireplace in the centre of the room, which was common for the 13th century, but the central window was converted into a modern open fireplace around 1580.

To the west of the Knights' Hall is the three-storey Solar Block, an irregular, elongated building measuring up to 7.9m × 11.9m. The room on the 1st floor probably served as a solar (dining room for the family), the ground floor as a room for servants. The knights' hall and solar block were built at the same time in the 13th century, the masons removing the fixtures from the old Norman tower behind the knights' hall. They were probably built in two stages and were intended to be smaller, less representative buildings. However, plans changed as construction progressed. They were hastily completed, traces of which can still be seen today along with other changes made in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The northwest and northeast towers behind the northern buildings are of Norman origin, from the 11th and the beginning of the 12th centuries. They were created by arching the curtine outwards until the desired external shape was created. Then wooden floors and a wooden wall were inserted at the back. The wooden parts of the towers were later replaced by stone components and inserted into the series of later buildings. The northeast tower, or Pendover Tower, was originally two stories high. A third storey was added in the 14th century and the interior was substantially remodelled in the 16th century. It has chamfered external corners to make attacks more difficult, though this weakens the structure of the tower as a whole. The north-west tower also had such chamfered corners, but the abort tower was added in the 13th century and changed its external appearance. Two other Norman towers survive to this day in the innermost courtyard, the West Tower, also called Postern Tower because it contained the rear entrance ('postern gate'), and the South West Tower, also called Oven Tower because of its cooking facilities. The Norman towers looked out over the land towards Wales, presumably for symbolic reasons.

A series of buildings, which no longer exist, once extended from the innermost courtyard to the knight's hall. These included a large stone house, 16.5 m × 6.1 m, which extended along the courtyard, and on the side opposite the innermost courtyard the main kitchen, 9.4 m × 7 m, which was built at about the same time as the knights' hall. To this was added a furnace building, 6.4 m × 8.2 m in size.

The Great Tower or Donjon is situated on the south side of the innermost court. It is a roughly square building, four stories high. Most of its walls are 2.6 m thick, except for the newer northern wall, which is only 2.3 m thick. The Great Tower was built in various stages of construction. Originally it was a relatively large gatehouse in the original Norman castle, probably with sleeping chambers above the passage. It was then converted into a donjon in the mid 12th century, but continued to serve as a gatehouse for the core castle. When the innermost courtyard was created in the early 13th century, the passage was filled in and a new entrance was created into the core castle to the east of the Great Tower. Finally, in the mid-15th century, the north side of the building was rebuilt, creating the Great Tower in the form visible today. The donjon has a vaulted ground floor, 6.1m high, with Norman wall arches and a series of windows on the 1st floor, but most of these have been bricked up over time. The arches are the equivalent of those in the chapel and probably date from 1080. The windows and large passageway must have looked impressive, but were also very difficult to defend. This type of tower was probably modelled on the earlier Anglo-Saxon statue towers and was intended to show the high social standing of the owner. On the first floor there was originally a high hall, 8.8 m × 5.2 m in size, which was later divided into two floors by drawing in a ceiling.

Chapel from the early 12th century

·

The chapel of St. Mary Magdalene with the two levels of masonry and plaster preserved until today...

·

...the entrance...

·

...the interior with the arched niches...

·

...and the hewn console.

The main kitchen (right) in front of the innermost courtyard and the entrance to the core castle (left)

Mortimer's Tower and towers of the core castle in the distance

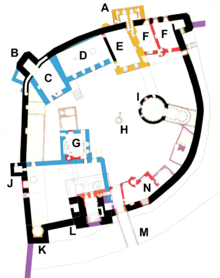

Core Castle: A - Abort Tower; B - North West Tower; C - Solar Block; D - Knights Hall; E - Parade Bedroom Block; F - Tudors' Chambers and North East Tower; G - Main Kitchen and Pantry; H - Well; I - Chapel of St Mary Magdalene; J - West Tower; K - South West Tower; L - Great Tower; M - Moat and Bridge; N - Judges' Chambers. Periods: black - 11th/12th century; purple - 12th century; blue - 13th century; yellow - 14th century; orange - 15th century; red - 16th century; light purple - 17th century; dashed - ruined buildings.

Questions and Answers

Q: Where is Ludlow Castle located?

A: Ludlow Castle is located in Ludlow, England.

Q: Why was Ludlow Castle important during the Middle Ages?

A: Ludlow Castle was important during the Middle Ages because of its position on the border between England and Wales.

Q: Who were some famous residents of Ludlow Castle?

A: Some famous residents of Ludlow Castle were Prince Arthur, the son of King Henry VII of England, and Prince Edward, the future King Edward V of England.

Q: Is Ludlow Castle still intact?

A: No, most of Ludlow Castle is ruined.

Q: Can visitors go to Ludlow Castle?

A: Yes, visitors are allowed to go to Ludlow Castle.

Q: When was Ludlow Castle built?

A: The exact date of the construction of Ludlow Castle is not known, but it is believed to have been built in the late 11th century or early 12th century.

Q: What is the significance of Ludlow Castle today?

A: Today, Ludlow Castle is a popular tourist attraction and historical site. It offers visitors a glimpse into the past and the important role that the castle played during the Middle Ages.

Search within the encyclopedia