Lothal

22.521388888972.2494444444Coordinates: 22° 31′ 17″ N, 72° 14′ 58″ E

Lothal [/ˈloːtʰəl/] (Gujarati લોથલ 'Hill of the Dead') was an important city of the ancient Indus culture. Located in the present-day state of Gujarat and dating back to the 24th century BC, it is India's most important archaeological site from this era.

Lothal is located near Saragwala town in Dholka taluk (an administrative unit) of Ahmedabad district, six kilometres southeast of Lothal-Bhurkhi station on the Ahmedabad-Bhavnagar railway line, and is also connected to the all-weather roads to Ahmedabad (85 km), Bhavnagar, Rajkot and Dholka. The nearest towns are Dholka and Bagodara.

The quay/quay of Lothal - the oldest known quay in the world - connected the town to an ancient course of the Sabarmati on the trade route between Harappa in Sindh and the Saurashtra peninsula, when the surrounding Kachchh desert was part of the Arabian Sea. In olden times, it was a bustling and flourishing trading centre from where pearls, gems and precious jewellery were traded all the way to the Near East.

After the discovery in 1954, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) conducted the excavation from February 13, 1955 to May 19, 1960. This unearthed the settlement and the port area. After the resumption of excavation, the archaeologists laid search trenches on the northern, eastern and western flanks of the mound and discovered the canals and nullah (canyons or gullies) connecting the port with the river. The finds included a mound, a settlement, a marketplace, and the harbor. Near the excavation site is the Archaeological Museum, which displays one of the most famous collections of objects from the Indus culture in modern India.

Lothal was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List in 2014.

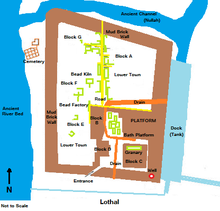

Plan of the excavation of Lothal

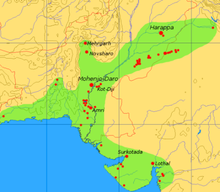

Extent and most important sites of the Indus culture

Archaeology

The meaning of the name Lothal, which is a compound of the Gujarati words Loth and (s)thal and translates as "hill of the dead", is not unusual as the name of the town of Mohenjo-Daro in Sindhi means the same. People in the later neighboring villages of Lothal knew of the presence of an ancient city and human remains. Boats could sail up to the hill as late as 1850, and timber was brought by boat from Bharuch to Saragwala in 1942. A silted river branch between present-day Bholad and Lothal and Saragwala shows the ancient course of a river.

After the partition of India in 1947, most of the Indus culture cities, including Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, fell into Pakistani territory. The Archaeological Survey of India therefore began a new research project and discovered several sites around Gujarat. Between 1954 and 1958, more than 50 sites were excavated in the Kutch and Saurashtra peninsulas, revealing that the Indus culture extended 500 km further east to the river Kim, where Bhagatrav borders the Narmada and Tapti river valleys. Lothal is 270 km from Mohenjo-Daro in Sindh.

Given the relatively small dimensions of the city centre, there has been speculation that Lothal as a whole was not a large settlement and that the supposed port may have been an irrigation reservoir. However, the ASI and other archaeologists assert that the city was part of a river system on the ancient trade route from Sindh to Saurashtra in Gujarat.

Finds in cemeteries suggest that the inhabitants may have been of Dravidian, proto-Australoid or Mediterranean physiognomy. Lothal offers the largest Indian collection of prehistoric archaeological finds. Essentially, the finds are of the Indus culture. In addition, there existed an indigenous Mica Red pottery, which probably pre-dates the Indus culture in time. Two sub-periods of the Indus culture are distinguished; the main period (2400-1900 BC) is identical with the actual culture of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

In Lothal, the Indus culture was still flourishing when it had already decayed in Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa. But tropical storms and floods caused immense destruction that destabilized the culture and eventually brought it to an end. Topographical analysis indicates that the region was suffering from drought and weaker monsoon rains at the time of its demise. Thus, the reasons for the city's abandonment can be seen in both climatic changes and natural disasters, as indicated by magnetic records of the surrounding area.

Lothal is located on a hill that was a salt marsh flooded by the tide. Remote sensing and topographic studies published in 2004 by Indian scientists in the Journal of the Indian Geophysicists Union reveal an ancient meandering river near Lothal (30 km long according to satellite imagery), which is an ancient extension of the northern riverbed of a tributary of the Bhogavo. The small width (10-300 m) compared to the lower reaches (1.2-1.6 km) suggest that the flood reached to the city or even further. The upper parts of the river were a useful source of fresh water for the inhabitants.

To the northwest of Lothal is the Kutch Peninsula, which until recently was part of the Arabian Sea. Therefore, and because of its proximity to the Gulf of Cambay, the river of Lothal provided direct access to the sea routes.

History

Before the arrival of the Harappa culture (c. 2400 BC), Lothal was a small site near a river that provided access to the mainland from the Gulf of Khambhat. The inhabitants maintained a flourishing economy, attested by the discovery of copper objects, beads and semi-precious stones. There were ceramics made of fine, smooth clay with a red mica surface. They improved the technique for firing pottery under partial-oxidizing and reducing conditions. The inhabitants bore the name Meluḫḫiter in the Sumerian language.

The Harrappa people were probably most interested in the sheltered harbor, the rich cotton and rice fields, and the pearling industry. In the west there was probably a great demand for pearls and precious stones from Lothal. The new settlers apparently lived peacefully with their predecessors, who adopted their lifestyle, as evidenced by the flourishing trade and changing work techniques. The Harrappa people began to produce ceramic goods in the manner of the indigenous population.

Urban planning

A flood destroyed the foundations of the city and settlements around 2350 BC. The Harrappa people from the vicinity of Lothal and Sindh took the opportunity to expand their settlement and carry out urban planning along the lines of larger cities in the Indus Valley. The planners of Lothal wanted to protect the area from floods. They divided the city into blocks with one to two meter high platforms of sun-dried bricks, on each of which 20-30 houses were built of thick mud and bricks.

The city consisted of a citadel or acropolis and a lower district. The rulers lived in the acropolis, which offered tiled baths, underground and above-ground drains of toasted bricks, and a drinking fountain. The lower part of the city consisted of two sectors. The main street, running north-south between the residential areas, served as a commercial center; shops of rich and simple merchants and craftsmen were located along the roadside. In its heyday, the lower town was regularly enlarged.

For the engineers, the construction of the harbor and warehouse had the highest priority to meet the needs of maritime trade. While the majority of archaeologists identify this structure as a port, there are voices that speak of an irrigation basin and canal. The port built to the east of the city is considered an engineering feat. It is located away from the central course of the river to avoid silting, but provides access for ships even at high tide. The warehouse is located on a 3.5 m high podium made of mud bricks near the acropolis, so that the rulers could monitor the activities in the harbour and warehouse. A 220 m long jetty on the west side of the harbour, which was connected to the warehouse by a ramp, facilitated the transport of goods.

Opposite the warehouse there was an important public building, the superstructure of which has completely disappeared. During its history, the city was often exposed to floods and storms. The port and the city walls were preserved. The zealous reconstruction of the city increased trade. As prosperity increased, however, care for the built structures declined, possibly as a result of overconfidence in their systems. A flood of moderate magnitude revealed some weaknesses in 2050 B.C., but the problems were not adequately addressed.

Economy and urban culture

The uniform organization of the city and its institutions show the discipline of the Harappa people. Commerce and administration conformed to the standards known from the Indus Valley. The town administration was very strict - the width of most streets remained the same for a long time and no structures were built on top of them. Homeowners had septic tanks or holding tanks to collect garbage so it didn't clog sewers. Drains, manholes and septic tanks kept the town clean and diverted garbage into the river, which was washed out by the flood.

A provincial style of art developed; this included portraits of living creatures in their natural environment as well as depictions of stories and folklore. Fire altars were erected in public places. Metalware, gold, jewelry, and tastefully decorated ornaments show the culture and prosperity of the people of Lothal. Their equipment - metal tools, weights, measures, seals, earthenware and ornaments - were in accordance with the standard and quality of Indus culture.

Lothal was an important trading centre, importing en masse raw materials such as copper, silica and semi-precious stones from Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa and selling them to towns and villages. Large quantities of bronze tools, fish hooks, chisels, spears and ornaments were also produced here. Lothal exported beads, gems, ivory, and shells. The stone industry was oriented towards domestic needs and fine silica was imported from the Sukkur valley or from Vijayapura in present-day Karnataka. Bhagatrav supplied semi-precious stones, while shells came from Dholavira and Bet Dwarka. The trade network, which provided great prosperity to the inhabitants, extended across the borders to Bahrain and Sumer.

Years of decay

While the debate about the end of the Indus culture continues, archaeological evidence from the ASI suggests that Lothal perished due to natural disasters such as floods and storms. Around 2000-1900 BC, a powerful flood inundated the city and destroyed most of the houses, severely damaging walls and platforms. The Acropolis and the Residence were razed to the ground and subsequently populated by common merchants and makeshift new houses. The most serious consequence was the altered course of the river, which prevented access to the ships and the port.

Although the ruler left the city, the people built a shallow entrance to the river to let small ships in. People built new houses without removing the debris from the flood, which made housing quality suffer and later damage more likely. Public sewers were replaced with drainage vessels. Citizens rebuilt public baths and kept fire worship. With a poorly organized government and no outside influence or central government, it was not possible to reasonably repair or maintain the public facilities. The storehouse was never adequately repaired and supplies were stored in wooden tents where they were threatened by floods and fires.

The economy of the city changed. The volume of trade dropped considerably, but not catastrophically, and resources were less plentiful. Independent businesses collapsed, resulting in a merchant-centered system of factories where hundreds of craftsmen worked for the same supplier and financier. The bead factory had ten parlors and a large work yard. The coppersmiths had five furnaces and tiled basins where several artists could work.

The declining prosperity of the city, lack of resources and poor administration increased the woes of the flood and storm-ravaged residents. Increasing salinization of the soil made the land barren, as is evident in the neighboring towns of Rangpur, Rojdi, Rupar, and Harrapa in Punjab, and Mohenjo-Daro and Chanhudaro in Sindh. In 1900 BC, a flood destroyed the flagging city in one fell swoop. Archaeological analysis shows that the basin and harbour were clogged with silt and debris and the buildings were destroyed to the ground. The flood affected the entire region of Saurashtra, Sindh and southern Gujarat, as well as the upper reaches of the Indus and Satluj rivers, where many towns and villages were washed away. The population fled inland.

Later Indus culture

According to archaeological evidence, the area continued to be inhabited, albeit by a smaller population with no urban way of life. The few people who returned to Lothal were unable to rebuild and repair their city. Nevertheless, they stayed and held on to their religious traditions, living in simple houses and reed huts. That they were Harrappa people is shown by the analysis of their remains in the cemetery. While the trade and resources of the city had almost completely disappeared, the people retained various idiosyncrasies of writing, pottery and other products.

Around this time, ASI archaeologists record a mass exodus from Punjab and Sindh to Saurashtra and the Sarasvati valley (1900-1700 BC). Hundreds of ill-equipped settlements have been attributed to these people, called late Harappa people, a totally deurbanized culture characterized by rising illiteracy, monotonous economy, inadequate administration and poverty. Although the Indus seals fell into disuse, the system of weights with a unit of 8.573 grams remained.

Between 1700 and 1600 BC, trade was revived. In Lothal there was mass production of ceramics such as bowls, plates and jugs. Traders used native materials such as chalcedony instead of silica for stone blades. Polished sandstone weights replaced the previous hexagonal weights. The sophisticated Indus script was simplified by ridding it of pictographs and reducing pictorial elements to wavy lines, loops, and fronds.

The archaeological site of Lothal

The structure with bathroom and toilet in the houses of Lothal

An old well and the drainage channels of the city

Search within the encyclopedia