Linear Pottery culture

![]()

This article is about LBK - for ALK see Alföld linear ceramics.

The Linear Pottery Culture, also known as Linear Bandkeramische Kultur or Bandkeramische Kultur, technical abbreviation LBK, is the oldest farming culture of the Neolithic period in Central Europe with permanent settlements. The introduction of this culture, also called Neolithic, subjected the pre-existing cultures to a comprehensive change; this is accordingly referred to as Neolithization, the epoch beginning with the LBK as the Early Neolithic. The historian Friedrich Klopfleisch introduced the term "Bandkeramik" into the scientific discussion in 1883, derived from the characteristic decoration of the ceramic vessels, which show a band pattern of angular, spiral or wavy lines.

With the emergence of the Linear Pottery culture came a series of technical-instrumental and economic innovations, such as pottery production, improved tool and implement manufacture, sedentarization, agriculture, animal husbandry, house and well construction, and the construction of ditchworks. It was a period of economic change from an appropriative, extractive form of economy to a food-producing economy, which was accompanied by the emergence of immobile property and stockpiling for group members.

In Anglo-Saxon literature, Linear Pottery is referred to as English Linear Pottery culture or Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics or as English Incised Ware culture. Other terms, though more of the general type are: "first European farming population/farmers" also as English European Neolithic farmers (ENFs) or Early European farmers (EEF) and, referring to their original origin, also as "Anatolian Neolithic farmers", English Anatolian Neolithic farmers (ANFs).

Distribution of the regionally earliest archaeological culture with pottery (c. 6000-4000 BC, c. 7,500-5,500 BP): Western LBK Alföld linear ceramics or eastern LBK cardial or impression culture Ertebølle culture, Mesolithic culture Dnepr Don Culture Vinča culture La Almagra Culture Dimini culture, previously Sesklo culture Karanovo Culture Cambrian culture, Mesolithic culture Note: The map is inaccurate and needs revision; it only gives the approximate territorial conditions of individual cultures. Some cultures are missing.

Origin of the band ceramics

The Linear Pottery reached the northern loess frontiers in Central Europe from 5600 to 5500 B.C. According to some common doctrines, it emerged from the Starčevo-Körös cultural complex. This is how especially the earliest Bandkeramic settlements in Transdanubia, excavated in recent years, are interpreted. The vessels of the oldest Bandkeramik are characterized by flat-bottomedness and organic leanness, they strongly resemble the late Hungarian Starčevo pottery. Around 5200 B.C., a different style asserts itself, the ceramics are now round-bottomed and inorganically magmented. Settlements of this transitional stage were found, for example, at Szentgyörgyvölgy-Pityerdomb (small area of Lenti), Vörs-Máriaasszonysziget (Lake Balaton) and Andráshida-Gébarti-tó (near Zalaegerszeg). The research group led by Barbara Bramanti (Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz) examined ancient DNA from banded ceramic skeletons. The findings suggest that the bearers of the Linear Pottery migrated from the Carpathian Basin to Central Europe about 7500 years ago. From there, the Bandkeramics could have spread in two directions, firstly via Bohemia and Moravia along the Elbe to central Germany, and secondly via Lower Austria along the Danube to southwest Germany and further along the Rhine.

According to this immigration hypothesis, there is no anthropological continuity from Europeans of the Late Mesolithic to the Linear Pottery. Neither they nor the Bandkeramics are to be seen as ancestors of today's European population (see the section The Bandkeramics and the Question of the Ancestors of Modern Europeans). A 2010 study even found matches between the DNA of Bandkeramic graves from Derenburg (Saxony-Anhalt) and the present-day population of the Near East. So there, at the site of the Neolithic Revolution, the ancestors of the Bandkeramics would have to be sought.

The described immigration hypothesis did not remain unchallenged: The archaeologist Claus-Joachim Kind (1998) argued that the Bandkeramikers could be an autochthonous development in the European Neolithic. Thus, flint artefacts in the oldest Bandkeramik pointed to Mesolithic traditions. Also, the similarities between ceramics from the oldest Linear Pottery and those from the Starčevo-Körös cultural complex are low; this rules out immigration from those cultures.

An autochthonous, then probably partly multilocally developed Linear Pottery culture could have been established at the respective site by vertical cultural transfer (i.e. a certain relationship between tradition and innovation); however, this does not fit very well with the striking uniformity of the culture in its distribution area. This uniformity suggests a horizontal cultural transfer by transmigration, i.e. indigenous Mesolithic populations may have adopted the Neolithic way of life from migrating groups (without perishing because of it). A corresponding further doctrine points particularly to the continuity of material culture. Thus, the flint implements of oldest Linear Pottery settlements showed Mesolithic traits, which is evident in "faceted impact surface remains" (faceted SFR) both in certain shapes (cross-cutters, trapezoids, etc.) and in the preparation of the impact surfaces. The Bandkeramik also detaches itself from a differently shaped religious background, as Clemens Lichter (2010) notes. For example, the newly appearing circular grave systems did not exist in the Starčevo-Körös complex.

It is unclear what share the so-called La Hoguette group had, which was spread from Normandy (where the eponymous site is located) to the Main-Neckar region. This culture is assumed to have had a pastoral livelihood, i.e. non-sedentary sheep or goat herders, who maintained strong economic links with the Linear Pottery since the spread of the LBK. The La Hoguette group can be derived from the Cardial or Impresso culture, an early Neolithic culture that can be chronologically placed before the Starčevo-Körös complex and was widespread along the coasts of the western Mediterranean. From the mouth of the Rhone it spread northwards around 6500 BC, reaching the Rhine and its tributaries as far as the Lippe about 300 years before the Bandkeramik. The proportion of domestic animal bones in the finds of the La Hoguette culture is significantly greater than that of the Linear Pottery, who conversely practised much more agriculture. Since there is evidence of intensive contact between the two cultures, it is quite conceivable that the La Hoguette herders and the Bandkeramik farmers profited economically from each other.

Bandkeramische Gefäße aus Mitteldeutschland im Bestand der ur- und frühgeschichtlichen Sammlung der Universität Jena, which Friedrich Klopfleisch used in 1882 to define the Bandkeramische Kultur.

Origins and spread of Neolithic agriculture in the period

Ecological framework and economy

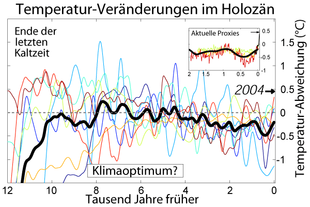

According to Schmidt et al. (2004), a warm, maritime climate with relatively high precipitation is assumed for Central Europe during the Linear Pottery Culture. Their interpretations were revised on the basis of the dendrochronological findings of Holm (2011). The warm optimum called the Atlantic, also called the "Holocene Optimum", lasted in northern Europe from about 8000 to 4000 B.C. The Atlantic was the warmest and wettest period of the Blytt-Sernander sequence, according to another source also the warmest epoch of the last 75,000 years. Both average summer and winter temperatures were 1-2 °C higher than in the 20th century; winters in particular were very mild.

In Europe, the Atlantic period showed regional temporal differences, and there were also brief interruptions. One such temporally sharply delimited climate change is the Misox Oscillation around 6200 years B.C. During this, it became colder by about 2 °C within a few decades in Middle Stone Age Central Europe. The Misox Oscillation coincides with the last discharge of Lake Agassiz into Hudson Bay. This enormous freshwater input into the North Atlantic largely suppressed the formation of higher-salinity water, which sinks because of its higher density. The resulting impairment of thermohaline circulation (convection) in the North Atlantic primarily weakened the North Atlantic Current as the northern branch of the Gulf Stream. The northward heat transport decreased, and in northern Europe a regionally varying but considerable cooling and drying set in. Something similar was also observed at the same time in the Near East, especially in the Fertile Crescent (see also Preceramic Neolithic). The climatic consequences of the Misox fluctuation can be traced in the vegetation development of Europe for a good hundred years. A hydroclimate reconstruction by Joachim Pechtl and Alexander Land (2019) showed an extraordinarily high frequency of severe dry and wet spring-summer seasons throughout the LBK epoch. Furthermore, the study was able to provide evidence for a particularly high degree of annual fluctuation in the period from 5400 to 5101 BC and lower fluctuations until 4801 BC. Nevertheless, the authors were cautious in their interpretation of the significant influence of the regional climate on the population dynamics of the LBK, which had begun around the year 4960 BC.

With the development of a warm and humid period and an increase in average temperatures, dense mixed oak forests with demanding hardwood species spread. In addition to oak and lime, elms, birches, pines, various maples, willows, hazels as well as forest grasses and herbs occurred. Hornbeam and fir recolonized these areas not too long ago.

How can the deciduous forest in the Atlantic climate stage on loess soil be reconstructed? It was not an impenetrable forest with a strong undergrowth, but it was a forest that had only a small undergrowth. Elm and lime, which together with the oak determined the composition of the tree population, are characterised by a typically dense, branched tree crown, so that some undergrowth could only develop at the beginning of spring. The oak, on the other hand, has a much more open canopy, so that one has to imagine more semi-shade-loving plants under it.

Pollen analysis of soil samples shows the changes in the proportion of various woody plants in northern Central Europe associated with the Linear Pottery. The primeval oak forests offered the Linear Pottery people favourable conditions for settlement and forest grazing. The Linear Pottery people gained settlement and arable land by (partial) clearing and felled oaks to obtain wood for houses or palisades. It seems that they already made use of ringing and practised sluice building. In the course of time the number of oak and lime pollen decreased, while birch, hazelnut and ash pollen became more frequent; it is assumed that the above-mentioned clearings contributed to this change in the vegetation pattern. Elm in particular is of great importance as a source of food for livestock (forest pasture). The elm must have been one of the leading wood species in the valleys of the loess areas, because the higher degree of humidity of the soil is more favourable for this tree species than in the loess plains.

Multiple analyses of relict soils (palaeosols) as well as of the deposits contained in them provide information on palaeoenvironmental conditions. Such investigations showed that in many cases the Neolithic or Linear Pottery settlement was preceded by a steppe climate with black earth formation (chernozem). Humic acids and humins, which form the basis of the clay-humus complexes of the soil, are particularly important for sufficient plant nutrition, because humic substances can adsorb and thus store ions very well. Soils rich in grey and brown humic acids, in combination with the cold-age loess deposits or black earths, were a major reason for sustained agricultural yields. The mild, summer-warm climate of the Atlantic with its reliable weather patterns was a further prerequisite for the high agricultural productivity and the successful assertion of Neolithic cultures in Central Europe. However, parabraun soils were also encountered.

During this general climate change, Neolithic cultures first settled the low-lying loess areas. The rural settlement sites of the Linear Pottery people spread mainly along the smaller to medium-sized, branched and meandered river courses; in the case of the smaller river courses or streams, their upper reaches and headwaters were preferred. In the case of larger watercourses, the Linear Pottery people sought out the edges of the low terraces, i.e. slopes (relief energy) in the transitional area between alluvial landscapes and the flood-protected hinterland; they lived there in longhouses, mostly in group settlements of five to ten farmsteads. Cultivable loess soils were preferred, as were areas or microclimates with moderate rainfall and maximum warmth. There are indications that it was not the watercourses themselves that promoted settlement, but other factors occurring in the areas concerned, such as the loess soil, which influenced settlement, because conversely the landscapes on both sides of the river, which were largely covered with sandy soils, tended to inhibit settlement.

In the lowlands, the main stream of the rivers is usually accompanied by many tributaries due to the low flow velocity, and the surrounding landscape up to the natural high banks of the valley margins is constantly changed by the dynamics of the water flow. In these flood plains, floodplains are created, which are characterised by the constant alternation of flooding and drying out.

These preferences can also be well related to the climatic changes during the settlement history of the Linear Pottery: In large parts of their settlement area, microclimatic changes occurred from rather dry-warm to wetter conditions. After such changes, the Neolithic people chose other settlement sites, because increased rainfall led to more violent floods occurring in narrower periods (flowing water type), from which the Linear Pottery settlements in the upper third of a slope were better protected.

Typically, more differentiated vegetation communities were found on the fertile loess sites, such as the winter lime-oak-hornbeam forest and the woodruff-beech forest. Here, depending on the season, forest grazing (hute) and leaf haymaking (Schneitelwirtschaft) were practiced. According to Ulrich Willerding (1996), cattle grazing in the forest was mainly reserved for summer fodder production, while the production of leaf hay was used for winter storage. In this respect, Linear Pottery forest clearing and grazing for agriculture and livestock farming are the beginning of the anthropogenic change of the dominant ecosystem, the forest history of that epoch.

The fauna included forest-typical mammals such as wild boar, roe deer, bison, elk and red deer. Typical predators included badgers, lynxes, foxes, wolves and brown bears. The proportion of bones from wild animals varies greatly in the individual settlements, but decreases from the early cultures to the later ones.

Arable farming or crop production

·

Cultivated einkorn with husks (Triticum monococcum)

·

Pea plant

(Pisum sativum)

·

Lentil vetch

(Vicia ervilia)

·

bolls

With paleo-ethnobotanical evaluations of the soil samples the cultivated plants could be determined, was proven:

- Emmer (Triticum dicoccum) and einkorn (Triticum monococcum)

- Naked and spelt barley (Hordeum vulgare)

- Trespe species, such as the grass species named Bromo lapsanetum praehistoricum by Karl-Heinz Knörzer in 1971, were typical companions of emmer and einkorn; trespe is a sweet grass species, its seeds made up about one third of the large-grained grass fruits in many samples besides einkorn and emmer, so that it can be assumed that trespe was not regarded as a "weed" but was consumed

- Peas (Pisum sativum)

- Lentil vetch (Vicia ervilia)

- Lentils (Lens spec. ) and linseed (Linum spec. ) were also known, as were celery (Apium graveolens), mustard seeds (Sinapis arvenis), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and thistle (Origanum vulgare).

Another source also mentions spelt (Triticum aestivum subsp. spelta) and restricts flax cultivation to the species Linum usitatissimum (common flax). Isolated finds prove the use of rough wheat (synonym: naked wheat; Triticum turgidum L. ), panicum miliaceum (Panicum miliaceum) and oats (Avena spec. ).

All listed cereals can be sown as winter cereals in autumn or as summer cereals in spring. The harvest was then staggered in the summer. A distinction is made between spelt cereals (emmer, einkorn, spelt barley, spelt) and naked cereals (naked wheat) according to the type of grain hull. In the case of spelt cereals, the husks enclosing the grain are more or less firmly attached to it. In the case of naked grain, on the other hand, they are loose and fall off during threshing. The advantage of spelt cereals is that they tolerate primitive storage better; the disadvantage is that the grains have to be dehusked before milling; for this, however, they must be completely dry.

Summarizing and semi-quantifying, the Linear Pottery cultivated most frequently the spelt wheat species emmer and einkorn in the loess soils. Less common were the cultivation of naked and spelt barley. Other cereals such as spelt, oats, rye and millet were only found in isolated cases.

The Linear Pottery cultivated other plants than the Cardial or Impresso culture (see above the section Origin of the Linear Pottery). Only when both currents met later in the Main-Neckar-Rhine area did poppy cultivation reach the Linear Pottery. This can be assumed to have been the case since about the Early Linear Pottery. Only in the Late Linear Pottery Binkelweizen (Triticum compactum) became important. Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) was collected as a wild fruit. The knowledge about the food supply is of central importance for the reconstruction of the living conditions of the inhabitants of Linear Pottery settlements; among other things Black elder (Sambucus nigra), crab apple (Malus sylvestris), blackberries (Rubus fruticosus), wild strawberries (Fragaria vesca), beechnuts (Fagus sylvatica), blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), cornelian cherries (Cornus mas), or poppies (Papaver somniferum).

In addition to geoclimatic research, the listed geoecological research also points to a very mild climate during the spread of the Bandkeramic culture in Central Europe.

Cultivation techniques and soils

The Linear Pottery people were probably hoe farmers in the sense of Eduard Hahn (1914), whereas Lüning assumes the use of the plough. In cultures practicing hoe cultivation, the digging stick is the most important tool; however, this has so far only been attested for the later Egolzwil culture.

In 1998, Manfred Rösch was able to demonstrate an increase in both the density and the species richness of spontaneous accompanying vegetation in cultivated plant stands (so-called "weeds") through botanical analysis of soil samples in various southern German Linear Pottery settlement sites. These data are consistent with summer-only cropping. However, whether the increase in associated vegetation is indicative of fallow or perhaps just grazing cannot be discerned from the evidence. The mass occurrence of some weeds and the evidence for a poorer nitrogen supply of the soils suggest that the agricultural production conditions deteriorated during the course of the Linear Pottery culture.

Arable farming and early calendar systems

For agriculture, even more than for animal husbandry, it was important to be able to determine the times for sowing and harvesting independently of the specific weather conditions. Early calendar systems are generally based on observations of nature and weather. The course of the year is divided into repeating corresponding phenomena without counting them. An observational calendar is based on natural, usually astronomical events (such as the position of the sun, the phases of the moon, the rise or position of certain stars). With the occurrence of a certain defined celestial event (such as the new moon or the equinox in the Central European spring), a new cycle is initiated.

In cultures such as the Bandkeramian, which practiced agriculture, the calendrical recording of the seasons becomes necessary. Therefore, parallel to the transition from a Mesolithic to a Neolithic society or from a hunter-gatherer society to a sedentary way of life, a transition from the lunar to the solar calendar is assumed (see in this regard the Stichbandkeramik and the circular excavation site of Goseck).

Game or hunting animals, pets

Wildlife, wildlife use

On the other hand, the ratio of domestic to hunted wild animals in the settlements was regionally very different. In different ways, all these farm animals provided not only meat but also skin, horn, hides, sinews and bones as sought-after raw materials for slaughter.

In the oldest Linear Pottery settlements, c. 5700/5500 to c. 5300, the evaluation of the animal bones found, for example by Stephan (2003), suggested that in certain areas the Linear Pottery settlers certainly built on the technological traditions of the indigenous Mesolithic hunters, fishermen and gatherers. During excavations in an early Linear Pottery settlement at Rottenburg-Fröbelweg, animal bones were recorded qualitatively and quantitatively. However, in addition to domestic and farm animals representing the usual range of species from the Linear Pottery onwards, such as cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and dogs, it became apparent that they were only represented in low frequencies. Thus, they do not seem to have made a major contribution to the meat supply of the settlement inhabitants. In contrast, the hunting of the then common wild mammals red deer, roe deer and wild boar was of striking importance. According to Stephan (2003), high proportions of wild animals were also observed in other, though not all, contemporaneous sites in southern Germany. According to Schmitzberger (2009), bones of four species - red deer, roe deer, wild boar and aurochs - together accounted for 89% of all wild animal finds identified to date. On the other hand, wild horses, European wild asses, elk and bison were certainly also sought-after prey, but due to the rarity of their bones in the find material, they were apparently more difficult for LBK hunters to reach in the terrain studied.

Bandkeramic pets

The composition of the bone finds of domestic animals in the early Linear Pottery hamlets was on average relatively uniform; about 55% domestic cattle (Bos taurus), 33% sheep / goats (Capra aegagrus hircus) and 12% domestic pigs (Sus scrofa).

The immigration hypothesis for the origin of the Bandkeramics suggests that the farm animals (and seed plants) were not created by domestication or breeding from the Central European wild stock, but were brought with them. Analyses of mitochondrial DNA show that pigs in Central Europe came from the areas of present-day Turkey and Iran. It can also be confirmed that all European cattle are descended from the Eurasian subspecies of the aurochs (Bos primigenius taurus), whose original home is in Anatolia and the Near East; they are therefore not descended from tamed European aurochs.

Domestic Cattle

Domestication into domestic cattle already took place before the 9th millennium BC, i.e. in the Epipalaeolithic. Evidence shows that from 8300 B.C. onwards, cattle arrived together with farmers on Cyprus, which had been cattle-free until then; studies of the mitochondrial DNA of recent domestic cattle also show that the current haplotypes of Central European domestic cattle breeds resemble those of Anatolian cattle breeds.

However, it is as yet uncertain whether the present distribution pattern of domestic cattle in Europe dates back to the early Neolithic epoch. There is evidence of gene flow between Near Eastern Anatolian populations in the early phase of the European Neolithic, but this is limited to the period after 5000 BC. This is interpreted as evidence of long-distance trade. Accordingly, eastern populations domesticated from the mid-9th millennium BC reached western Anatolia and the Aegean region before 7000 BC, and after 6400 BC genetic diversity declined with westward migration. The Neolithic settlers thus reached the southern Mediterranean, but also southern France, by boat, but initially with very few (female) livestock. Without any significant gene flow from the native bovids, their descendants reached Central Europe around 5500 BC, and Northern Europe around 4100 BC. Especially during the immigration to Central Europe, genetic diversity was again lost.

Furthermore, it is documented that band ceramics often castrated their bulls. Oxen are less aggressive and more tractable than bulls, also less muscular than those, but more muscular than cows. Because the growth plates close later in castrated male mammals, steers grow much longer than bulls and become larger than those. The delayed closure of the growth plate also affects the bony basis of the horn, the horny cone (processus cornualis), which forms the frontal bone in horn-bearing ruminants. Therefore, oxen can be distinguished from bulls by the horn cones.

The Bandkeramics apparently used the cemented milk of their cattle. However, the level of milk production of Neolithic cows differed markedly from that of modern cattle. For example, small, funnel-shaped vessels with perforated walls appeared at sites, which strongly resemble modern cheese-making devices. A working group led by Mélanie Salque (2013) was also able to detect milk fat in pottery sherds from Linear Pottery production. The emergence of lactase persistence (the ability of adults to digest milk) is also linked to the Linear Pottery culture.

The undergrowth of the contemporary mixed oak forests provided domestic cattle with rather sparse food, so that larger forest areas were required if the animals were to cover their ongoing energy needs through grazing. This resulted in a critical size of herd kept for each Bandkeramic settlement. This varied with the location, but also with the type of farming, such as long-distance grazing with winter use of deciduous fodder or animal husbandry close to the settlement, made possible by improved arable farming.

Bandkeramic sheep

Probably, according to Jens Lüning et al., the "bandkeramic sheep" did not yield sufficient wool as a secondary product. This is because the development of the sheep's coat from wild sheep to a woollier coat with fewer prickly hairs took place over a longer period of time (towards the end of the Neolithic). It is possible, however, that the people of the Neolithic gradually used the shed fur hairs that accumulated during the seasonal change of coat to produce yarn and fabric.

Bandkeramic domestic pigs

Although the keeping of pigs seems to have been of less importance in a comparison of the Linear Pottery households, the finds (bones, sculptures, idols) in some hamlets suggest a higher rate of use of these domestic animals.

Bandkeramic dogs

Already in the settlements of the rural, bandkeramic cultures of Central Europe there were dogs, which were found in graves and settlements, such as in the Swabian Vaihingen an der Enz. These are not supposed to be wolf-like dogs, but medium-sized breeds. In 2003, a separately buried peat dog (Canis palustris) was found in the Bandkeramic settlement of Zschernitz in Saxony. The dog from Zschernitz had a shoulder height of about 45 cm, which is compared to the size of today's Spitz. It can be assumed that the Neolithic dog breeds of the Bandkeramics already had the ability to differentiate between domestic and farm animals on the one hand, which had to be protected or kept intact, and huntable game on the other. Also, the loss of the (wolfish) flight behaviour in case of imminent danger and the lack of aggression behaviour despite the predator-prey relationship in the human communities in the canine behavioural repertoire was one of the essential prerequisites for the differentiation of the Neolithic domestic dogs from the wolf. Since the Middle Stone Age the dog was domesticated so Raetzel-Fabian (2000).

Possible livestock diseases and adverse health effects

For questions of hygiene, it appears significant that livestock farming expanded the spectrum of possible pathogens. A change in the microbiome surrounding humans began as a result of the closer coexistence of LBK and their farm animals or the corresponding cultural successors. Thus, the so-called zoonosis can be transmitted from humans to animals (anthropozoonosis) or from animals to humans (zooanthroponosis). Thus, cattle are susceptible to bacterial zoonoses such as tuberculosis, salmonellosis, brucellosis or anthrax and are therefore possible vectors of these diseases. The nematode (Trichinella spiralis) can infest cattle, other mammals and also humans. Other parasites such as the large liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) also infect humans as well as cattle; the same applies to eukaryotic protozoa such as cryptosporidia. Cattle are even intermediate hosts of a human parasite, the bovine tapeworm (Taenia saginata). Bovine brucellosis is a so-called mating disease. It is caused by the bacterium Brucella abortus of the genus Brucella when it infects domestic cattle. Cattle are the main host, while almost all mammals including humans and poultry are secondary hosts. Bovine haemorrhagic septicaemia caused by the pathogen Pasteurella multocida can also affect humans, albeit non-specifically. On the other hand, leptospirosis of cattle, as Weil's disease, can be quite dangerous for humans.

Regarding other health impairments, a study by Klingner (2016) on a total of 112 adult individuals of the LBK from Wandersleben (Thuringia) found skeletal evidence that would indicate diseases related to domestic smoke production at the fireplaces; chronic exposure to smoke gas. But there was also strong evidence for cases of tuberculosis in the finds.

Unbalanced vegetarian diets favored alteration of the oral cavity microbiome or dental biofilm and were associated with increased incidence of dental caries.

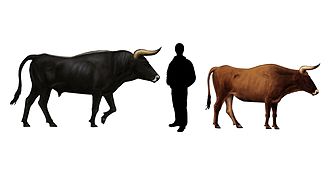

Living reconstruction and size proportions of an aurochs (Bos primigenius), the wild ancestral form of the domestic cattle (Bos taurus):on the left a bull: 170-185 cmin the middle a band ceramist: 170 cm on the right a cow: about 165 cm

Linseed (Linum usitatissimum)

Dirmstein's Loess Wall

Turning left stumps and root systems (modern image, as indicated by the smooth break edge and step); the result was an anthropogenic clearing of the woods

Reconstruction of the earth's temperature course at the end of the last cold period and in the following 12,000 years. The heyday of the Linear Pottery culture was between 5500 and 4500 BC.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Linear Pottery culture?

A: The Linear Pottery culture was an important culture in the Neolithic of Europe, from 5500–4500 BC.

Q: What is the abbreviation for the Linear Pottery culture?

A: The abbreviation for the Linear Pottery culture is LBK.

Q: What is another name for the Linear Pottery culture?

A: The Linear Pottery culture is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics or Incised Ware culture.

Q: Where is the most evidence for the Linear Pottery culture found?

A: The most evidence for the Linear Pottery culture is found in Central Europe.

Q: What is the significance of the Linear Pottery culture?

A: It is important evidence for early farming in Europe.

Q: What kind of pottery is associated with the Linear Pottery culture?

A: The pottery associated with the Linear Pottery culture has simple cups, bowls, vases and jugs, without handles, and had line patterns on them.

Q: What was the purpose of the pottery in the Linear Pottery culture?

A: The pottery was made as kitchen dishes, or for carrying food and drink.

Search within the encyclopedia