Libyan Civil War (2011)

![]()

This article is about the Libyan civil war in 2011. For the currently ongoing conflict, see Civil war in Libya since 2014.

First Libyan Civil War

Part of: Arab Spring

The 2011 civil war in Libya, also known as the February 17 Revolution, broke out in February of that year in the wake of the Arab Spring. It began with demonstrations against Muammar al-Gaddafi's rule and intensified after unrest in Tunisia, Egypt and Algeria. The official date of the start of the revolution is February 17, 2011. The political conflict escalated into military conflict and divided the country's leadership. Parts of the diplomatic corps and the armed forces joined the opposition. A National Transitional Council emerged and took control in the east of the country.

After the United Nations authorized the international community to take military action to protect civilians in Libya in Resolution 1973, the United States, United Kingdom, and France began an air and naval blockade and airstrikes on government forces and military installations on March 19, 2011, as part of the International Military Operation in Libya. The airstrikes supported opposition ground forces in capturing towns in the west of the country. A few days after opposition forces captured Tripoli in August 2011, the Transitional Council was moved to the capital.

On October 20, after weeks of fighting, Gaddafi's native city of Sirte was captured. In the process, Gaddafi, whose whereabouts had been unknown since the fall of Tripoli, was captured and killed under unexplained circumstances. According to the Transitional Council's account, Gaddafi died in the hours afterward from a bullet to the head that struck him in crossfire between supporters and opponents as he was being transported to the hospital. The autopsy result leaves questions unanswered, and a no-doubt account of the circumstances of his death has yet to be given. Both the UN Human Rights Council and the International Criminal Court are calling for the circumstances of Gaddafi's death to be clarified. On 23 October, the Transitional Council declared the country fully liberated.

At the end of the war, the number of war dead was estimated at between 10,000 and 50,000. According to Libyan government figures from 2013, about 10,000 people died during the civil war in Libya, about 5,000 each for Gaddafi supporters and rebels. The numbers are much lower than those previously reported by the new health ministry (30,000 dead on the rebel side alone). Around 60,000 Libyans were injured and need medical treatment.

Since the end of the civil war, large parts of the country have been under the control of revolutionary brigades that do not report to the National Transitional Council. Political observers speak of a power struggle between the revolutionary brigades and the Transitional Council. In February 2012, there was fighting between the revolutionary brigades, which no one intervened against.

In January 2012, torture was reported in prisons, most of which, however, are not under the control of the Transitional Council. According to a report by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), around 8,000 people were still being detained as a result of the war in September 2013, mostly in detention centres not under government control, where torture is frequent. The only reason for detention is often membership of an ethnic group or tribe, to which loyalty to Gaddafi is attributed.

The year 2014 marked the beginning of the continuation of the warlike clashes between the Council of Deputies and the New General National Congress.

Since the beginning of the uprisings against the Gaddafi regime, opposition forces mostly used the former flag of the United Kingdom of Libya.

Muammar al-Gaddafi at the African Union Summit, 2009

Background

Libya was ruled since 1969 by the authoritarian Muammar al-Gaddafi, who exercised his power indirectly, in a permanent revolutionary leadership established parallel to the state structures. With its oil resources, the Maghreb state led the African continent in the Human Development Index, with scores comparable to Bulgaria, Brazil or Russia, but was among the countries with the most widespread corruption. The Reporters Without Borders organization listed Libya 160th out of 178 countries in its 2010 press freedom ranking. Arbitrary arrests, ill-treatment and torture of opposition figures were commonplace. The unemployment rate was officially reported at 20.7 percent, while other estimates put it at 30 percent (2001). At the same time, before the mass exodus in February 2011, the number of migrant workers employed in the country was estimated at about 1.7 million, which represented a quarter of the total population. Although Libya clearly topped the UN education index among African countries, ahead of South Africa, the main reason for the high unemployment rate compared to other Maghreb countries was seen to be the lack of skilled labour, it was suggested that this was due to an inadequate education system and low productivity among the local population. Presumably, this was related to the rapid opening of markets by the Gaddafi regime since the end of economic sanctions in 2003. Libya led Africa in school enrolment, even ahead of the US, France or Sweden. Due to the oil resources in the country, there was an extremely wealthy upper class; the Gaddafi family's fortune was estimated to be between $80 billion and $150 billion at the time of their rule. Libya is a member of OPEC and was one of Europe's most important suppliers of gas and oil.

Historical power structures and regional contrasts

After the Second World War, Great Britain and France occupied Libya and tried to prevent its independence. Tripolitania and Kyrenaika were under a British military government, Fessan under a French one. In 1946 Idris al-Mahdi al-Senussi returned to Cyrenaica from his exile in Egypt and called a national congress in 1948, at which major differences arose between the Egyptian-oriented eastern Libyan nationalists and the Tripolitan representatives. Finally, on 1 June 1949, he declared himself Emir of "Independent Cyrenaika". Britain recognized the Independent Cyrenaica. Because they did not accept the exclusion of Tripolitania, the United Nations had a constitutional plan for Libya drawn up and elections prepared. On this basis, a unified Libya became independent under its constitutional king, Idris I, on January 1, 1951. However, Great Britain and the USA still maintained military bases, which were only closed by the Gaddafi regime in 1970 (Royal Air Force Station El Adem and Wheelus Air Force Base).

Libyan society is characterized by tribal structures. The tribes of eastern Libya's Cyrenaica were historically strongly oriented towards the Senussi order, which Idris I had presided over. The Senussi dynasty was deeply rooted in Cyrenaica and had strong support among the tribes there.

On September 1, 1969, the Libyan military putsched itself into power under a revolutionary council, whose leadership was assumed by Colonel Gaddafi. Eastern Libyans were distanced from the abolition of the monarchy and the subsequent reform policy. Identification with the new form of government was much lower than in Tripolitania, the more populous western part of the country.

Nevertheless, since 1969 Libya's political ruling class has come predominantly from Cyrenaica. However, Gaddafi filled important positions in the state and security apparatus with members of his own clan and entered into alliances with other large tribes, which were rewarded with posts. The government's preference for other tribes and the resulting unequal distribution of oil wealth led to discontent, particularly in Cyrenaika, which repeatedly manifested itself in violent clashes. Since the 1990s, there have been repeated distribution struggles and attempted coups.

Religious motives

The insurgency was linked to Islamic extremism by Libyan revolutionary leader Gaddafi and Libyan state television, which he controlled. In a speech on February 24, 2011, shortly after the revolt began, Gaddafi said the uprisings were inspired by the extremist organization al-Qaida. Foreign terrorists, he said, had given Libyan youth drinks laced with hallucinogenic pills, inciting them to demonstrate.

Gaddafi's government had been confronted with religiously motivated opposition since the 1980s. This was especially true in the east of the country, where demonstrations against Gaddafi's government were widely attended at the beginning of the uprising. According to a U.S. Embassy report, the interpretation of faith in Cyrenaica is more conservative than in other parts of the country. While Gaddafi initiated a course of political and economic liberalization in 1988, he opposed the "religious tendency to hijack politics." The religiously motivated opposition sometimes took on violent forms. During Ramadan in 1989, for example, armed attacks on mosque visitors accused of being too close to the government have been documented. The extremist organization Libyan Islamic Fighting Group carried out an armed insurgency in the east of the country beginning in June 1995. According to a former British intelligence agent, Britain's MI6 allegedly assisted the group in the 1996 assassination attempt on Gaddafi. According to media reports, members of this group joined the armed struggle against Gaddafi's government.

The military and political leaders of the insurgents nevertheless rejected any connection to extremism. Western observers from the countries intervening militarily in Libya also disputed Gaddafi's statements. NATO General James Stavridis stated in a U.S. Senate hearing that militant groups had not played a significant role in the uprising, according to available intelligence. U.S. Chief of Staff Mike Mullen also said he did not detect any al-Qaida presence among the insurgents.

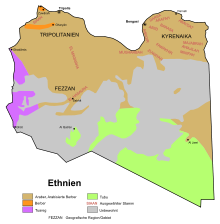

The three historical governorates of Libya (1943-1963)

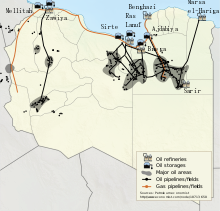

Oil and gas reserves, pipelines and refineries in Libya 2011

Ethnic groups and tribes in Libya (according to 1974 CIA data): Arab and Arabized Berber Berber Tuareg Tubu uninhabited

History

→ Main article: Chronicle of the civil war in Libya (2011)

Demonstrations

The first protests took place in mid-January 2011. At the end of January, the Libyan writer and opposition activist Jamal al-Hajji called for protests against the regime and was arrested shortly afterwards. On February 6, 2011, Abdul Hakim Ghoga, Medhi Kashbur and two other lawyers from Benghazi were allowed by Gaddafi to enter his tent in Tripoli. With "So you're with the Facebook kids now, too," Gaddafi is said to have opened the conversation. Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak deserved their fate for not listening to their people and imposing their sons as successors, Gaddafi is reported to have said. The delegation called for freedom of the press, freedom of expression and a constitution, saying Libyan youth needed housing, a good education and jobs. Gaddafi disagreed: "All the people need is food and drink".

On February 15, following calls on the Internet, demonstrators gathered in various cities in Libya to protest, chanting slogans against "the corrupt rulers of the country" or "There is no God but Allah, Muammar is an enemy of Allah." The protests had been led by relatives of those killed in the Abu Salim prison massacre fifteen years earlier, after their lawyer Fathi Terbil was arrested. Violent clashes with security forces broke out in Benghazi, Tripoli, Al-Baida and several other cities. A day of rage was declared for February 17 by the opposition led by Abdul Hakim Ghoga; demonstrations took place in all major Libyan cities. Dozens of demonstrators were killed. According to eyewitness reports, groups of armed mercenaries targeted the population with heavy weapons, and special police units fired into the crowd from rooftops. Tanks were also reportedly used against civilians. The regime blamed foreign rioters for the violence.

Expansion to the uprising and collapse of the regime in parts of the country

→ Main article: Libyan National Liberation Army

In the following days, the violent clashes escalated into civil war-like conditions. Occasionally, security forces and army officers defected to the insurgents. Benghazi, the most important and largest city in eastern Libya, fell into the hands of insurgents on February 20. Various other cities followed, so that after about a week of fighting, practically the entire region of Cyrenaika was controlled by the rebels.

In several cities in Tripolitania, however, the armed uprisings by government troops have been put down for the time being. One exception was Misrata, the country's third-largest city, which had been controlled by the rebels since April 2011 after fierce fighting. The Gaddafi regime's troops were driven out of the city, but were able to prevent the insurgents from advancing further towards Tripoli for some time. Another rebel stronghold, the Jabal Nafusa in the border region with Tunisia, was also the scene of changing battles.

Counterattacks by the Libyan government and alleged mercenary operations

Reinforced by suspected mercenary troops, the Libyan army, which had been put on the defensive in many cities at the beginning of the conflict, had fought back with extreme force. There were attacks by the Libyan air force on rebel strongholds in which numerous civilians were killed. According to the insurgents, these operations were essentially carried out by several thousand black African mercenaries flown in by Gaddafi for this purpose.

In embattled cities such as Tripoli and Misrata, snipers are said to have fired indiscriminately on civilians. In early March, government forces launched an offensive that retook eastern Libyan coastal towns such as Ras Lanuf, Brega and Ajdabiya. On March 19, Libyan government forces had advanced to Benghazi and launched an attack on the rebel stronghold. Calls for the international community to intervene had become increasingly urgent. The international military operation began that day with the deployment of French fighter jets over Benghazi in Opération Harmattan, destroying the heavy weapons on the side of the Gaddafi units and helping the rebels beat back the attack.

Corresponding reports spread via Twitter and found great resonance in the international media via Al Jazeera and al-Arabiya. An investigative report by the UN Commission on Human Rights confirmed the involvement of a smaller number of war participants of foreign origin on both sides, but in no case could it identify mercenary activities as defined by the UN conventions. Many of those arrested or executed as suspected mercenaries were said to be dark-skinned Libyans or migrant workers from sub-Saharan countries. At the end of June, Amnesty International's Donatella Rovera stated that no evidence of the existence of mercenaries had been found during investigations in recent months, calling it a "persistent myth". Contrary to this statement, various media report that numerous foreign fighters are fighting on the side of Gaddafi's troops against the Libyan opposition.

Development of the situation after the start of the international military operation

→ Main article: International military operation in Libya 2011

On 17 March, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1973 authorising the establishment of a no-fly zone over Libya and the protection of the civilian population by military means. Massive air strikes followed, particularly by the French and US air forces, against advancing Libyan forces and strategic targets throughout the country. The Libyan army's advance on the rebel stronghold of Benghazi was thus halted. In addition, Libyan air defenses were largely disabled, leaving airspace controlled by allied forces. Days later, rebels were able to recapture strategically important cities such as Ajdabiya and Brega. International air strikes played a significant role in the success of the recapture. The advance of the troops, which consisted largely of militarily untrained volunteers, was repeatedly beaten back despite air support. After the recapture of Ras Lanuf and Brega by government troops and a failed advance by the Libyan army on Ajdabiya, a stalemate developed between government troops and rebels.

In particular, the city of Misrata, which has been surrounded by government troops since 3 April, came into the focus of world attention. The besieged city was under heavy fire for weeks due to the continued attacks of the government troops slowly advancing towards the city centre, and the collapse of the food supply for the population and the medical care for the countless wounded became apparent. The government troops withdrew again to the outskirts of the city on April 23 because of fierce defensive fighting. They continued their attacks from a distance for weeks, firing rockets into the city, but in turn were better able to take fire from NATO forces than in the confusing house-to-house fighting.

In the mountainous region of Jabal Nafusa, which is mainly inhabited by Berbers and is in part only a little more than a hundred kilometres from the capital Tripoli, the rebels succeeded in April in bringing the important border crossing to Tunisia under their control despite ongoing counterattacks. Not only aid supplies but also weapons and volunteers from Gaddafi-controlled regions reached the mountainous region via this supply line. By the summer, after fierce fighting, the rebels had largely driven the pro-government forces out of the mountain towns and onto the plains below. Stable control of an area so close to the capital was a crucial prerequisite for the further advance on Tripoli in August.

As the war progressed, NATO airstrikes acted as support for the capture of more positions from the Gaddafi regime by opposition forces.

Occupation of Tripoli

The capital Tripoli initially remained under the control of the Gaddafi government. During the fighting, Gaddafi repeatedly referred to the insurgents in televised speeches as criminals, Islamist terrorists and drug addicts. He announced that he would die as a martyr if necessary and would never step down voluntarily.

On August 20, 2011, an uprising that had been in preparation for some time began in Tripoli under the code name "Operation Mermaid Dawn"; at the same time, rebel troops advanced from the Nafusa Mountains towards Tripoli. They were significantly supported by fighters from Tripoli and az-Zawiya who were familiar with the area. The date is doubly symbolic, firstly because a conquest of Tripoli was to be achieved before the end of Ramadan on 29 August, and secondly because 20 August is traditionally celebrated as the anniversary of the Battle of Yarmuk, in which an Arab army won a decisive victory over the superior Eastern Roman army in 636.

On 21 August, the rebels managed to advance into Tripoli, meeting minimal military resistance and often being welcomed by the population. NATO had helped prepare and flank the advance with airstrikes. While the media reported the progressive capture by the rebels, the status of some parts of the city remained unclear. For example, Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi spoke freely to journalists at the Rixos Hotel on August 23, despite the fact that the National Transitional Council had announced his arrest. The Rixos Hotel, where the government had held press conferences and where many journalists were still staying, remained under control of the regime supporters for a long time.

The fighting in Tripoli was concentrated in the center, where soldiers of Gaddafi's regime supporters defended Bab al-Aziziya until the evening of August 23. How long Muammar al-Gaddafi, his sons and important regime representatives had remained there remained unclear.

The Gaddafi regime lost control of Tripoli to the Transitional Council towards the end of August 2011. Meanwhile, in the rest of Libya, the rebels had captured almost all the major northern cities. By early October, only the cities of Bani Walid and Sirte, Gaddafi's hometown, remained in the hands of Gaddafi supporters.

Ibrahim Abu Sahima, the head of the new government's committee to search for victims of Muammar Gaddafi's rule, announced on 25 September 2011 that investigators from the National Transitional Council in Tripoli had found a mass grave containing the remains of 1270 people. These are said to be former inmates of Abu Salim prison, where a massacre occurred in June 1996 following protests by detainees. Sahima announced that the Transitional Council would ask for international help in identifying the dead. The bodies had been doused with acid, apparently to destroy evidence of the massacre. Both Jamal Ben Nur of the Libyan Transitional Council's Justice and Human Rights Ministry and a CNN crew that was on the scene spoke of "bones too big for human bones" and "animal bones," respectively. Neither mentioned the use of acid.

Occupation of the remaining cities of Libya until the fall of Sirte

Towns in Fessan and Tripolitania controlled by Gaddafi supporters were occupied by troops of Gaddafi's opponents, sometimes for a long time fought over, often supported by NATO air forces. Ghadames on the Tunisian border was taken on 29 August, the desert city of Sabha on 22 September, Bani Walid on 17 October, and the last city to be taken on 20 October, after weeks of fighting, was Gaddafi's birthplace Sirte.

Gaddafi, who had holed up in his hometown of Sirte after the fall of Tripoli, attempted to flee the besieged city in a convoy of cars on October 20. After the convoy was heavily shelled by NATO aircraft, the Transitional Council announced that day that Gaddafi had been captured wounded but had died shortly afterwards under as yet unexplained circumstances. The autopsy report said the cause of death was a gunshot wound to the head, which occurred after his capture on the way to the hospital in crossfire between supporters and opponents of Gaddafi. Gaddafi's military chief Abu Baker Junis Jabr was also killed. The UN Human Rights Council is calling for the circumstances of Gaddafi's death to be clarified. The tentative assumed location of his discovery and capture: 31.19562° N, 16.52141° E31.19562276166716.52140975.

Situation after the civil war

→ Main article: Civil war in Libya since 2014

![]()

Parts "elections [...] to be held in June 2012" seem to be out of date since July 2012.

Please help to research and insert

the missing information.

Wikipedia:WikiProject events/past/missing

Since the end of the civil war, more than 6,000 people have been arrested, so far without any official charges or prospect of a trial. In the detention centres in the city of Misrata, which are not under the control of the National Transitional Council but of the local revolutionary brigade, prisoners are tortured. The aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières recorded torture injuries in a total of 115 detainees. The torture interrogations, some of which were fatal, were conducted by the military intelligence service NASS. Local authorities had ignored the aid agency's calls for an end to torture. After the torture death of the former Libyan ambassador to France in Sintan became known, Justice Minister Ali Hamida Ashur said those responsible would be brought to justice; the prisons affected by allegations of torture were mostly not under the control of the Transitional Council. Amnesty International published several reports on systematic torture by rebel forces in irregular detention facilities. The black African population in particular was the target of rebel reprisals.

On 23 January 2012, the capture of large parts of the city of Bani Walid by 'Gaddafi supporters' was reported. Arrests of former Gaddafi supporters allegedly ordered by the National Transitional Council were cited as the trigger for the uprising. The following day, it was denied that Bani Walid was now controlled by supporters of Gaddafi. The city had merely wanted its own local government. They had resisted interference from the capital. After consultations with tribal representatives in Bani Walid, Usama al-Juwaili, the defense minister of the National Transitional Council, recognized the local government.

Almost simultaneously, opponents of Gaddafi violently stormed the headquarters of the National Transitional Council in Benghazi. The reason given was dissatisfaction with the lack of transparency of the Transitional Council. The head of the Transitional Council, Mustafa Abd al-Jalil, then spoke of a dilemma: "Either we counter this violence with a heavy hand. That would lead to a military confrontation, which we don't want. Or we split, and there will be a civil war!"

Usama al-Juwaili wants to integrate the revolutionary brigades into the regular Libyan armed forces, the police and other institutions of the new government. However, there is often fighting between revolutionary brigades from different parts of the country against which the government does not intervene; for example, at the beginning of February 2012 in Tripoli near the city center between the brigades from Misrata in the east and Sintan in the west of the country. The reason is believed to be disputes over spheres of influence. In November 2011, representatives of the brigades declared that they wanted to keep their weapons until a new constitution was in force.

As recently as August 2011, elections to a constituent assembly were announced to take place in June 2012. The draft electoral law provides for numerous restrictions aimed at excluding supporters of Gaddafi from running for office. The law was passed in Tripoli on 29 January. According to the law, 136 seats of the Constituent Assembly are to be allocated to candidates of political parties and 64 seats to independent candidates. According to a member of the Transitional Council, the fact that 2/3 of the seats are to go to candidates of political parties is due to pressure from the Muslim Brotherhood; it is the only political grouping that can count on a majority in the elections.

On January 10, 2012, Transitional Council Foreign Minister Ashur Bin Hajal confirmed that Libya had received $20 billion of the funds frozen due to US sanctions. It is not confirmed whether the money was deposited with the Central Bank of Libya. In total, around 150 billion US dollars are said to have been frozen. The UN Security Council had lifted the sanctions on December 17, 2011. The absence of funds in Libya is causing discontent in the country. Businessmen are asking "where the money has gone".

The IMF warned on 30th January that the government's finances were still in a "dangerous" state. There is a $10 billion deficit in the 2012 budget, and the government is struggling to pay salaries and energy bills. According to the head of the Transitional Council, oil revenues in the past five months amounted to only $5 billion, but the cost of salaries and energy is $14 billion per year. Of the 100 billion US dollars frozen and released by the sanctions, only 6 billion US dollars are back in the country; they are working on getting the rest. At the same time, the organisational structures are being prepared together with the local councils so that public employees can be paid as soon as the money is available.

In early March, tribal leaders and militias in eastern Libya declared the region of Barqa, or Cyrenaika, semi-autonomous in the face of opposition from the central government. Contrary to the restoration of the original major province, they additionally laid claim to parts of the Fezzan oil region.

The courthouse square in Benghazi served as a central meeting and rally point. The walls are hung with photos of the fallen, with mourners constantly passing by - April 2011.

Libyan car with self-modified license plate, "Libya" was pasted over "Jamahiriya", in Zarzis (Tunisia)

Questions and Answers

Q: When did the Libyan Civil War begin?

A: The Libyan Civil War began in February 2011.

Q: What was the inspiration behind the Libyan uprising?

A: The Libyan uprising was inspired by the uprisings in neighbouring countries like Tunisia and Egypt.

Q: How did Muammar Gaddafi respond to the rebellion?

A: Muammar Gaddafi sent troops and tanks to break up the rebellion.

Q: Who started bombing during the Libyan Civil War?

A: Al-Qaeda started bombing during the Libyan Civil War.

Q: What did the rebels do during the Libyan Civil War?

A: The rebels in Libya began forming their own government.

Q: When did Muammar Gaddafi die?

A: Muammar Gaddafi died in October during the Libyan Civil War.

Q: How many people died during the Libyan Civil War?

A: Thousands of people died during the Libyan Civil War.

Search within the encyclopedia