Letter (message)

![]()

This article is about the written message letter, for further information see Letter (disambiguation).

The letter (from the 12th century originally as sentbrief in the current meaning, from Latin brevis libellus or in the 6th century from Late Latin breve' "short letter, document", to brevis 'short') is a message recorded on paper, usually delivered by a messenger and containing a personal message intended for the recipient. A letter is folded (Faltbrief), is as letter, Briefchen or Brieflein also a (pharmaceutical) name for bag or Apothekerbriefchen, or sent in an envelope (Umschlagbrief). In addition, it can also refer to a letter.

The letter usually consists of the indication of the place and date of writing, the salutation, the text and the closing formula. The envelope usually contains information about the sender, the recipient's address and, if mailed, postage paid.

The letter is a cultural product which has as its prerequisite the overcoming of illiteracy and which takes the development of written language as its basis. Its use as a communicative means presupposes a writing and reading competence (for example, as writing in a visual-graphic perception in the sense of writing, reading or the use of writing materials and writing carriers).

With the development of modern communication technologies, letters written on paper have increasingly lost their significance in recent decades.

Rudolf Epp: The Love Letter; c. 1896

Willem van Mieris: Reading old man, 1729

Personal letter

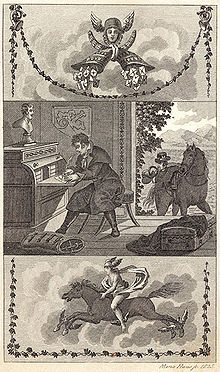

Hastiger Briefschreiber und Postillon, New non-profit letter writer for the bourgeois business life, Berlin 1825

"Post and Travel Map of the Ways through France" (1703).

Letters require writing materials, quills.

History

The beginnings of writing such a message go back to the Babylonians, who carved messages into clay tablets. In ancient Egypt, on the other hand, papyri were used to write letters. In ancient Greece and Rome, wooden tablets coated with wax were used for this purpose. Since the first writers of such communications, the purpose of a letter has hardly changed: It is still a means of expressing public opinion (e.g. letters to the editor in a newspaper), a literary form (cf. Goethe's epistolary novel "The Sorrows of Young Werther", the Pauline letters of the New Testament of the Bible) as well as an instrument for the dissemination of official (e.g. letters of the ministry of culture) and transmission of personal messages (e.g.: love letter). As early as the early modern period, the letter also developed into a collector's item; one of the largest collections preserved in Germany since then is that of Christoph Jacob Trew.

Letters are studied in the humanities according to historical, literary and cultural aspects. A pioneer of German letter research was the librarian and cultural scientist Georg Steinhausen, whose Geschichte des deutschen Briefes appeared in two volumes in 1889-1891.

History of the letter and the post in 18th century France

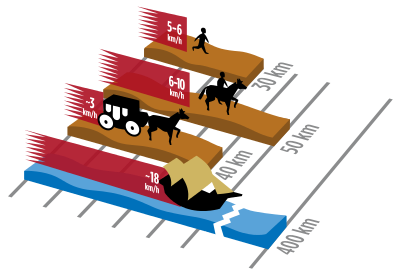

The letter transport system in the 18th century could, generally speaking, make use of different means of transport. These served a postal data exchange with different transport speeds.

A correspondence presupposes on the one hand the appropriate writing material as well as writing carriers and on the other hand the transport of the written texts etc. from one place to another. The postage letters (i.e. the recipient paid the transport fee) represented the rule. Postage means unpaid fee. As early as the 16th century, people in France noted en diligence (translated as "with haste", also "with care") on postal items. It is from this remark that French stagecoaches got their designation diligences. At the end of the 18th century, the steel quill was developed, which was set in a holder called a quill pen. Before that, quills were common and were gradually replaced.

Until the development of chlorine bleach (Eau de Javel 1789 by Claude-Louis Berthollet), the only available fibre raw materials for paper production were the light-coloured rags made from linen, hemp or very rarely cotton. In combination with spinning and ropemaking waste, this was used to produce so-called rag paper.

The main means of travel and transport available in the 18th century were movement on foot, independent horseback riding, travel in a carriage (stagecoach) or via waterways. In 1671, the Pajot and Rouille families established the first post office, premier centre Postal de Paris, in the centre of Paris (Paris City Post Office) at 34 rue des Bourdonnais opposite № 9 and 11 rue des Déchargeurs. They were Ferme générale des Postes under Louis XIV.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the letter post appeared, financed by contributions from the surintendant général des postes. A price was charged for the letter, which was paid by the recipient. Letters travelled from one postal station to the next, interrupted by relay stations where horses were changed. The mail transports were accompanied by a postillon. He was responsible for guiding them to each next station and then returned the horses to the original relay station alone. The distance of the relay stations averaged 7 French miles or 28 km, hence the famous seven-mile boots in Charles Perrault's tale Le Petit Poucet.

Postal and travel routes through France

In the 18th century, the average distance between two relay stations was 16 kilometres. A letter sent from Paris took 2 days and 8 hours to Lyon and just over 4 days to Marseille. There were about 1400 postal stations at that time. In 1760, Claude Humbert Piarron de Chamousset (1717-1773) founded a post office in Paris. With 200 postmen, facteurs - they drew attention to themselves with rattles - he ensured mail delivery and assured distribution within three days.

The "newspaper" letter

In the 16th century, a form of letter became common in Europe that approximated the newspaper (and has parallels to the social network on the Internet): "In order to send his messages to larger circles at once, the letter writer soon no longer addressed his letter to just one individual, but in the main to a larger number of like-minded people," noted the newspaper chronicler Ludwig Salomon in 1906. These letters consisted of two parts: the "intimate" part, which was in its own envelope inside the larger envelope, and a semi-public part placed loosely in the envelope, which the addressee was supposed to pass on to acquaintances and like-minded people if he thought it was interesting. This targeted distribution of news to a manageable circle gave rise to decentralized discussion circles and growing social networks among the correspondents of the time. The semi-public letter components were called Avise, Beylage, Pagelle, Zeddel, Nova, and finally just Zeitung. "The form in which the writers of these 'newspapers' reported their news was almost always purely relatoric" - that is, one of context, nothing hard researched, rather a collation of news and opinion.

The letter as a historical source

From the point of view of historiography, only the private letter is a "letter". If the author or the recipient is an official person or an institution, then the writing belongs to the documents or files. An "open letter", which in reality is addressed to the general public, belongs to literary works. However, because of the many mixed forms (e.g. business letters that also contain private matters), this terminology is not always compelling, even among historians.

Letters used to be very expensive and tended to be sent by officials or rich merchants; from the 18th century onwards, correspondence spread to wider circles of the upper classes. This century is also called the century of letters. Only occasionally, in important matters, did ordinary people also have letters written. In addition there was the profession of the letter writer. Often clichéd phrases were used, whereby much individuality was lost.

Since the 19th century, historical scholarship has also used surviving correspondence. In the 20th century, interest in everyday history and the history of the "little people" increased, so that the mail of these people also came increasingly into focus. Examples of this are soldiers' letters home from the world wars, which are not (only) of interest because of the individual fates, but because one would like to base statements about the life and mentality of larger groups of people on them.

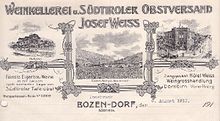

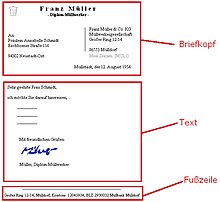

The letterhead

Letterhead refers to the elements usually pre-printed at the top of the first page of a paper letter. While they have always been limited to a few dates on private stationery and hardly show any decorative motifs (at most, for example, an embossed coat of arms), the elaborately designed letterheads of companies are definitely of historical interest. The simple beginnings date back to the beginning of the 19th century. With the increase in the movement of goods and the depersonalization of commercial dealings, it became increasingly important to have a representative external form for correspondence. Technically, this need was met by the rapid press patented in 1813 and an upswing in lithography from 1820 onwards. In addition to ornamental and allegorical decoration, popular motifs in the second half of the 19th century were above all factory views and decoratively arranged reproductions of prize medals.

Letterheads of public institutions are usually marked with the official coat of arms at the top centre or top right.

Postal

Until the 19th century, folded sheets were the usual form of a letter, while a special envelope was the exception. The form of a folded folio sheet became the normal size of the letter, about 9 × 17 cm, the average weight was about 1 lot or ½ ounce = about 15 g. All letters had to be sealed (abolished in 1849). The Post Office was not liable for the loss of a letter. The purpose of sealing was to protect the secrecy of the letter. The fee was negotiated individually from post office to post office, rarely were there fixed rates.

In the Kingdom of Westphalia, all shipments were to be calculated in francs and centimes. Since 1 November 1810, payment was based on distance and weight. The simple letter was allowed to weigh 8 g, consignments over 60 g were to be carried by the Fahrpost.

In the Duchy of Brunswick in 1814 the single letter weight was 1 lot, the price increased with each lot and the distance. In 1834, the single letter was only allowed to weigh ¾ lot, and the price increased from 1 lot by ½ lot for each ½ lot. Letters over 4 lots were to be carried by the driving post. From 1855 the simple letter was not allowed to weigh a full lot, the distance no longer mattered. From 1863, 1 groschen was payable for each 1 lot. In 1865 there were only two weight levels, up to 1 post lot = 1 groschen, up to 15 = 2 groschen.

In Prussia, the Posttaxregulativ of 1825 regulated letter postage according to distance and weight. A single letter was allowed to weigh ¾ lot. Letters weighing more than 2 lots belonged to the transport mail. In 1860, the letter weight was limited to 15 g (250 g) for domestic and club traffic. From 1861, single letter postage applied up to 1 lot, double letter postage up to 15 lots.

From 1830, commercially produced envelopes came onto the market, and they were produced by machine from 1840. In 1849, letters no longer needed to be sealed. In 1850 postage stamps were introduced, and in 1851 envelopes with imprinted stamps were added.

In the North German postal district, up to 1 lot = 1 Sgr. up to 15 lots = 2 Sgr. In the Reichspost 1875, up to 15 g = 10 Pfg. and over 15 g = 20 Pfg. The single letter weight increased to 20 g in 1900. At the same time, cardboard boxes and rolls were permitted.

Newly introduced were:

- 1897 official map letters as official form.

- 1908 Window envelopes.

- 1922 Official file letters up to 500 g.

- 1923 the maximum weight for letters was raised from 250 g to 500 g.

After the Second World War, the maximum weight was raised from 500 g to 1 kg in 1947. From 1948 to 1956, almost all items in the western zones or the Federal Republic had to be franked with the Notopfer Berlin tax stamp in addition to the postage. On 1 March 1963, standard letter items were offered at a special rate. In 1993, 4 basic products (standard, compact, large and maxi letter) were introduced by the Deutsche Bundespost. A standard letter has a maximum weight of 20 g and cost € 0.80 in 2020.

In today's world, letters are usually transmitted via postal services such as Deutsche Post, and their contents are protected by an envelope and the secrecy of correspondence. They should, but do not have to be sealed. Letters are usually prepaid (franked) by the sender. This is done by affixing postage paid indicia in the form of stamps, postmarks or imprints from the postal service provider. In addition, a postal address of the recipient must be written on the envelope, and if necessary also the address of the sender. This enables letters to be returned smoothly in the event that the recipient refuses to accept them or cannot be identified. Special forms of delivery are the German certificate of delivery, the Austrian return receipt letter and the internationally usable registered letter.

Due to the increased use of electronic mail and e-Postbrief, the importance of the classic letter has been declining for years. In 2008, Deutsche Post transported 16 billion letter items, but in 2017 the figure was only 12.7 billion. 92% of these were business letters.

Company letterhead of the winery Josef Weiss in Bozen-Dorf, used 1913

Letterhead of the Bavarian Prime Minister Söder (in official function)

Schematic representation of locomotion around 1800 - and thus also of the transport of letters. At 2 km/h, the carriage moved much more slowly than the messenger on foot, with a greater range (40 km instead of 30 km per day). The sailing ship had a speed of 18 km/h, which was only three times higher than the horse, but its range was on average about 400 km - that of the rider only 50 km.

Representation of a sample letter with letterhead, text and footer

Tax stamp "Notopfer Berlin

.jpg)

The Golden Letter of the Burmese King Alaungphaya from 1756 to the British King George II.

Standards

![]()

This paragraph presents the situation in Germany. Help to describe the situation in other countries.

The letterhead as well as the design of business letters is regulated in Germany by the German Institute for Standardization with the standard DIN 5008.

In cases where the address of the recipient has changed and a redirection order has been issued, letters with an outdated delivery address can also be redirected or forwarded to the recipient.

In the event of loss of the item, no liability is assumed in the case of an ordinary letter, see also the Post Office's obligation to pay compensation.

Electronic mail

Since the 1990s, traditional correspondence has been increasingly supplemented by e-mail, which has some considerable advantages (speed, price), especially for business correspondence. For the transmission of important texts (e.g. love letters, contracts, diplomatic notes), the letter form is still common. Since the advent of e-mail, conventional mail has also been jokingly called "snail mail" or "sack mail".

A special form of the letter is the advertising letter or the advertising mailing, also called mailing.

E-Postbrief

Deutsche Post's E-Postbrief was a hybrid mail service with an associated website for the exchange of electronic messages via the Internet. It was in competition with the legally regulated De-Mail process and had to be discontinued following a court ruling.

E-Postbrief

Search within the encyclopedia