Coccinellidae

![]()

Fraunkäfer is a redirect to this article. See also: ladybugs.

The ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae) are a globally distributed family of hemispherical, flying beetles whose coverts usually have a varying number of conspicuous spots. Many species feed on aphids and scale insects.

Ladybirds are popular among the population and have a wide variety of names in the respective local vernacular. One of the reasons for their popularity is that they are useful in horticulture and agriculture, as they eat up to 3000 plant lice or spider mites in their larval period alone, depending on the species. They are variable in appearance, which makes them difficult to identify. The same species can appear in dozens of pattern variations. Some, such as the alfalfa lady beetle, even reach over 4000 counted variants. In the past, these variants within the same species were given their own names, for example in the case of the two-spotted ladybird (Adalia bipunctata) with over 150 names, but these are no longer used today and are scientifically meaningless. In some subgroups - for example within the Tribus Scymnini - an identification can be difficult and reliable only on the basis of an examination of the genital organs. Besides the genitalia, the head capsule, the head shield and the antennae are often reliable distinguishing features of similar species.

The beetles can fly well and reach 75 to 91 wing beats per second. Some species such as the light ladybird (Calvia decemguttata) are attracted by artificial light at night. This suggests nocturnal dispersal flights.

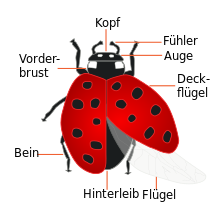

Body structure of the ladybird

.jpg)

Seven point when launching from a plant

Features

The body size of the strongly curved, short, hemispherical or oval beetles varies from 1 to 12 millimeters. The head, the chest and the underside are usually black. However, there are also beetles with light brown or rusty brown undersides. The color of the head usually depends on the color of the rest of the body and can be very different. The antennae are relatively long, usually eleven-limbed and club-shaped at the end. In some species groups the number of antennae is reduced. For example, the antennae of the Chilocorini have only eight or nine members and are therefore shorter. The ends of the mandibles of Central European species are hatchet-shaped. The mandibles are generally extremely variable between the different species, as the animals have adapted themselves to the particular food. Some species have a hairy body, but the upper wings of the best-known species are without structure and entirely smooth. In some species (for example, Chilocorini), the edge of the bracts is more or less curved upwards.

The legs are similar in construction to those of other beetles. The tarsi also consist of four limbs, but the second is strongly lobed and the third is often small. Only in a few species there is a reduction to three tarsal members.

Coloring

The body color can vary from light beige to yellow, orange, all shades of brown, pink, red and black. The best known representatives of the ladybirds have red, yellow, black or brown cover wings. The best known ladybird in Germany, the seven-spot ladybird (Coccinella septempunctata), owes its colour to lycopene, which also colours tomatoes red, and α- and β-carotene, which are also important for the colouring of most other species. The black color is produced by a melanin. In newly hatched animals, their coloration does not show until after a few hours. They are almost white or yellowish at first, and the chitin has not yet hardened. In the species Sospia vigintiguttata, the beetles are brown in the first year and only turn black during overwintering. Environmental influences affect the discoloration. It can occur from temperatures below 20 °C and is accelerated by high humidity and reduced by strong light irradiation.

In some species, different colorations also occur within the species, for example, there is the two-spotted ladybird beetle red with black spots, but also more rarely reversed as a black beetle with red spots (melanism). In maritime, humid areas and in large agglomerations with pronounced industry, significantly more black forms develop. This also suggests environmental influence. The black forms are more dominant than the red forms and therefore give birth to more dark offspring. The red form of the two-spotted ladybird has a higher chance of survival during hibernation, but the black forms reproduce better and compensate for the losses. The reason for this is that the beetles, like all insects, are poikilothermic. This means that their body temperature depends on the ambient temperature. Black colored body parts absorb more than red colored body parts. When illuminated, the body temperature of the black variant is about 5.5 °C, that of the red variant about 3 °C above the ambient temperature of 18 °C. This also accelerates the metabolic activity of the animals. In winter, however, this is a disadvantage because of the large temperature fluctuations. This is the reason for the higher mortality.

The striking coloration serves as a warning signal to predators. In addition, ladybugs have an unpleasant, bitter taste that makes them unattractive. In case of danger, they can also secrete a yellowish secretion from an opening in the joint membranes (reflex bleeding). On the one hand, this defensive secretion drives away enemies with its unpleasant odor, and on the other hand, it contains toxic alkaloids (coccinelline). At the same time, the ladybirds play dead (thanatosis) and retract their legs into small depressions (hollows) on the underside of the body. In certain species of Epilachnini, the yellow liquid is secreted from special dermal glands.

Points

The characteristic feature of ladybirds is the symmetrically arranged dots on their mating wings. They are usually black, but there are also beetles bearing light, red or brown dots, with species having 2, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22 and 24 dots. Within individual species, the dots may also vary. Either the beetles have none, or the dots blend together so that almost the entire body is black. Contrary to a common misconception, the number of dots does not indicate the age of the beetle; rather, the number of dots is characteristic of each species and does not change during the beetle's life. Within the close relatives of individual species (such as in the genus Coccinella) the dot variations are similar.

Larvae

The appearance of the larvae is very diverse depending on the species. Most of them are elongated and plump. Their length varies between 1.5 and 15 millimeters. Most are blue-grey, brown or yellow in colour and have yellow, orange or red spots. They have black or red warts distributed over their bodies, from which bristly hairs or spines emerge. Often their coloration can be used to infer the adult beetle. For example, the larva of the twenty-two-spotted ladybird beetle is yellow and black-spotted like the beetle. Except for the stethorini, they are covered with a layer of wax that protects them from ants, among other things. The larvae of some species (such as those of the seven-spotted ladybird) have relatively long legs and thus resemble "miniaturized dragonfly larvae".

Sexual dimorphism

In most species of ladybirds the sexes differ very little. The males are generally somewhat smaller and lighter than the females, but the values are too close together and vary so much that no determination can be made in this way. The fifth abdominal limb (sternite) of the females is somewhat more pointedly shaped than that of the males, but there are also species where not only the physique but also the coloration is different. This is the case with many species of the genus Scymnus or the fourteen-spotted ladybird (Propylea quatuordecimpunctata). There are also colour differences in the conifer ladybird (Aphidecta obliterata). The males are monochromatic brown, only the females develop differently pronounced dark areas on the mating wings.

The larva of an Asian ladybird during metamorphosis.

Freshly skinned ladybird larva

larva of the twenty-two-spot (Psyllobora.vigintiduopunctata)

Twenty-four spot (Subcoccinella vigintiquatuorpunctata)

Ladybug without points

Twenty-two point

Nutrition

The main food of many ladybird species and their larvae are aphids and/or scale insects. If the supply is large enough, they eat up to 50 per day and several thousand during their entire life. The beetles are therefore counted as beneficial insects and are bred for biological pest control. The food spectrum also includes spider mites, bugs, fringe winged beetles, beetle larvae, leaf wasps and occasionally even butterfly larvae. However, there are also species that feed on plants and thus are sometimes pests themselves (subfamily Epilachninae, including the twenty-four-spot ladybird). Still other species live on powdery mildew or mold (Tribus Halyziini and Psylloborini, including the sixteen-spotted ladybird and the twenty-two-spotted ladybird). When food is scarce, intrinsically predatory species sometimes resort to plant foods. This is often fruit, but also pollen. The larvae of Bulaea lichatschovi feed exclusively on pollen.

In the final larval stage, the larvae consume most of the food. This stage is accelerated by a high ambient temperature. This makes them, especially those of the genus Coccinella, more voracious, but altogether they consume fewer aphids, although these then multiply more strongly anyway because of the better conditions for them. On the other hand, in poor "aphid conditions" the Coccinella can contribute to the complete disappearance of the aphids. However, the number of hunters and prey regulates itself. Since the ladybird larvae react very sensitively to a lack of food, after a year with many aphids and the resulting many beetles, few beetles appear the following year because there is too little prey to ensure the development of all new larvae.

Ladybirds and especially their larvae are also cannibals. Especially in mass occurrences, the animals eat each other. The first hatching larvae also regularly eat their not yet hatched conspecifics, whereby often more than half of the eggs are lost.

grub feeding

Fourteen-spot (Propylea quatuordecimpunctata) feeding on an aphid

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the scientific name for lady beetles?

A: The scientific name for lady beetles is Coccinellidae.

Q: What type of fluids do they use to protect themselves?

A: Lady beetles use noxious fluids based on cyanide to protect themselves.

Q: How many species of lady beetle are there in the world?

A: There are over 5,000 species of lady beetle found worldwide.

Q: What do lady beetles typically feed on?

A: Lady beetles typically feed mainly on true bugs from the Hemiptera family, such as aphids and scale insects.

Q: How were Harmonia axyridis (or harlequin ladybugs) introduced into North America?

A: Harmonia axyridis (or harlequin ladybugs) were introduced into North America from Asia in 1988 to control aphids.

Q: When did Harmonia axyridis reach the UK?

A: Harmonia axyridis reached the UK in 2004.

Q: Are native species being out-competed by Harmonia axyridis in North America? A: Yes, native species are being out-competed by Harmonia axyridis in North America.

Search within the encyclopedia