Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (in short: Kyoto Protocol, named after the location of the conference Kyōto in Japan) is an additional protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted on 11 December 1997 with the aim of protecting the climate. The agreement, which entered into force on 16 February 2005, set binding targets for greenhouse gas emissions - the main cause of global warming - in industrialised countries for the first time under international law. By early December 2011, 191 countries and the European Union had ratified the Kyoto Protocol. The USA refused to ratify the Protocol in 2001; Canada announced its withdrawal from the agreement on 13 December 2011.

Participating industrialised countries committed to reduce their annual greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5.2 percent compared to 1990 levels within the so-called first commitment period (2008-2012). These emission reductions were achieved. There were no fixed reduction quantities for newly industrializing and developing countries.

After five years of negotiations - from the UN Climate Change Conference in Bali in 2007 to the UN Climate Change Conference in Doha in 2012 - the Parties agreed on a second commitment period ("Kyoto II") from 2013 to 2020. The main points of contention were the scope and distribution of future greenhouse gas reductions, the inclusion of newly industrializing and developing countries in the reduction commitments, and the amount of financial transfers. The second commitment period will come into force 90 days after it has been accepted by 144 Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. With acceptance by Nigeria on October 2, 2020, it will be in force for a few hours at the end of 2020. For the period after 2020, the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed on the Paris Agreement.

The increase in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere is mainly due to human activities, in particular the burning of fossil fuels, livestock farming and deforestation. The greenhouse gases regulated by the Kyoto Protocol are: Carbon dioxide (CO2, serves as a reference value), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (laughing gas, N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs/HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs/PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6); explicitly excluded are those greenhouse gases already regulated by the Montreal Protocol. The agreement could do little to change the overall growth trend of these key GHGs. Emissions of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide continue to rise; for example, CO2 emissions in 2019 were the highest ever determined. Emissions of various hydrocarbons have stabilised for other reasons, such as the protection of the ozone layer as a result of the Montreal Protocol.

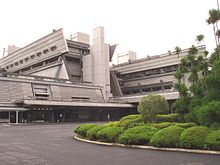

The Japanese city of Kyōto, the negotiating site of the climate protection protocol named after it.

Previous story

1992: Rio and the Framework Convention on Climate Change

In June 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) took place in Rio de Janeiro. Delegates from almost all governments as well as representatives of numerous non-governmental organizations traveled to Brazil for the world's largest international conference to date. Several multilateral environmental agreements were agreed in Rio, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In addition, Agenda 21 was intended to promote increased efforts to achieve greater sustainability, particularly at regional and local level, which henceforth also included climate protection.

The Framework Convention on Climate Change enshrines in international law the binding goal of preventing dangerous and human-induced interference with the Earth's climate system. It had already been adopted at a conference in New YorkCity from 30 April to 9 May 1992 and was then signed by most states at UNCED. Two years later, on 21 March 1994, it entered into force.

The Convention establishes a precautionary principle according to which concrete climate protection measures should be taken by the community of states even if there is not yet absolute scientific certainty about climate change. In order to achieve its goal, the Convention provides for the adoption of supplementary protocols or other legally binding agreements. These should contain more concrete commitments on climate protection and be structured according to the principle of "common but differentiated responsibilities" of all Parties, which implies that "developed country Parties [should] take the lead in addressing climate change and its adverse effects".

1995: The "Berlin Mandate" at COP-1

One year after the Framework Convention on Climate Change came into force, the first UN Climate Change Conference was held in Berlin from 28 March to 7 April 1995. At this Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the so-called COP-1, the participating states agreed on the "Berlin Mandate". This mandate included the establishment of a formal "Ad hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate" (AGBM). This working group was tasked with drafting a protocol or other legally binding instrument between the annual climate conferences that would include fixed reduction targets and a timeframe for achieving them. In line with the principle of 'common but differentiated responsibilities' enshrined in the Framework Convention on Climate Change, emerging economies and developing countries were already excluded from binding reductions at this stage. In addition, the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice (SBSTA) for scientific and technical issues and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) for implementation issues were established, and Bonn was chosen as the seat of the Climate Secretariat.

The then Federal Environment Minister Angela Merkel played a key role in the German delegation's far-reaching promise to commit itself at an early stage to the largest single contribution to greenhouse gas reduction among all industrialized countries. This early commitment is seen as a decisive factor in getting countries that were initially opposed to legally binding emission reductions on board by 1997.

1996: The "Geneva Declaration" at COP-2

In the run-up to the second Conference of the Parties in Geneva in July 1996, the Working Group on the Berlin Mandate, chaired by the Argentine Raúl Estrada Oyuela, had already held three preparatory meetings. In Geneva itself, the fourth meeting took place at the same time as COP-2. After a complicated voting process, the ministers and other negotiators present agreed on the Geneva Ministerial Declaration. In it, the conclusions of the Second IPCC Assessment Report, completed in 1995, were made the scientific basis for the further process of international climate protection policy, and the pending elaboration of a legally binding regulation on the reduction of greenhouse gases was reaffirmed. Resistance to explicit reduction targets that had been openly voiced at the Berlin Conference by the USA, Canada, Australia and especially the OPEC states was thus overcome.

1997: Last meeting of the working group on the Berlin Mandate

In the months leading up to the third climate conference in Kyoto, various components and drafts of a future climate protection protocol had been discussed in the meetings of the above-mentioned working group on the Berlin Mandate. In March 1997 at AGBM-6, for example, the EU had ventured an advance and proposed a 15% reduction in the three greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide in the industrialized countries by 2010. Within the influential group of industrialized non-member states of the EU, called JUSSCANNZ (consisting of Japan, the USA, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, Norway and New Zealand), the USA in particular was interested in the greatest possible flexibility within the future climate regime. Among other things, they introduced the proposal of emissions budgets into the debate, according to which emissions not used in one year but conceded could be counted towards a later year if a fixed reduction had not yet been achieved.

The JUSSCANNZ group hesitated to present concrete reduction targets and came under increasing pressure from the EU with another proposal. By 2005, according to the decision of the EU environment ministers in June 1997, the EU, together with other industrialized countries, would agree to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 7.5 %. The EU countries' renewed initiative was presented at the seventh AGBM meeting in August. In order to see their views reflected in a draft treaty text, JUSSCANNZ members now also had to make concrete proposals. The last opportunity to do so was the eighth meeting of the Working Group on the Berlin Mandate in October 1997, which was also the last official AGBM meeting before the Climate Change Conference in Kyoto in December. There, Japan presented its proposal for a maximum 5% reduction in the period 2008-2012 compared to 1990, with the possibility of downwardly deviating exceptions. The developing countries, on the other hand, exceeded the EU's offer by calling for a 35% reduction by 2020 and, at OPEC's request, the establishment of a compensation fund.

But the decisive factor was the USA and President Bill Clinton's proposal, which was broadcast on television to Bonn. It did not envisage any reduction for the period 2008-2012, but only a stabilisation of emissions at 1990 levels and a later conceivable, unquantified reduction. Clinton also called for the establishment of the "flexible instruments" of emissions trading and Joint Implementation (see below). Although less important points such as the location and equipment of the Secretariat, the subsidiary bodies and dispute settlement had been clarified, there was still disagreement on the central issue of the negotiations. It was thus up to the final conference of the negotiating cycle in Kyoto to produce a result.

At COP-2 in Geneva in 1996, important steps were taken to set the course for the second and final year of negotiations before the decisive conference in Kyoto in 1997.

The 1992 World Summit on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro produced the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the international legal framework for the Kyoto Protocol, which is based on it.

The 1997 World Climate Summit in Kyoto

In the two years following the decision on the Berlin Mandate, the working group set up for this purpose drew up the main features of the Protocol, which was then ready for final negotiation at the third Conference of the Parties, COP-3, in Kyoto in December 1997. The conference was huge: nearly 2,300 delegates had been sent from the 158 Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change and 6 observer states, non-governmental and other international organizations had sent 3,900 observers, and over 3,700 media representatives were present. The total number of people present thus amounted to almost 10,000. From 1 to 10 December, according to the timetable, the delegates had the opportunity to resolve the many unresolved issues of future climate policy.

The conference was divided into three parts. One day before the start of the COP, the eighth meeting of the AGBM of October 1997, which had not yet been formally concluded, was continued and ended on the same day largely without results. During the first week of the Kyoto negotiations proper, delegates were then expected to resolve as many outstanding issues as possible, and the remainder was left to the three-day meeting of the relevant national technical ministers at the end of the negotiating round.

The round of negotiations, originally scheduled to last ten days, developed into one of the most dynamic and unmanageable international environmental conferences ever held. In addition to the almost incidental discussions concerning the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the actual COP-3, a "Committee of the Whole" (COW) was established to conduct the climate protection protocol negotiations. As at the meetings of the AGBM, it was chaired by Raúl Estrada Oyuela. The COW in turn established several subsidiary negotiating rounds on institutional issues or the role and concerns of developing countries, as well as numerous informal groups that discussed topics such as carbon sinks or emissions trading.

The negotiations dragged on far beyond the planned time frame. It was not until 20 hours after their scheduled conclusion that the conference was actually declared over. At this point, the most important delegates had negotiated for 30 hours without sleep and with only short breaks, having hardly had a chance to rest in the days and nights before. In the end, a consensus was reached on the most important issues, including in particular precisely quantified reduction targets for all industrialised countries. However, many other critical points could not be resolved, but were postponed to meetings to be held at a later date.

Reduction targets adopted

The industrialised countries listed in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol committed themselves to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5.2% below base year levels in the first commitment period, the period from 2008 to 2012. Annex A of the Protocol lists six greenhouse gases or groups of greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4, HFCs, PFCs, N2O, SF6) to which the commitments were to apply. The base year was usually 1990, but there were two possibilities for deviation: firstly, some economies in transition set earlier base years for CO2, CH4 and N2O (for example, Poland set the year 1988 and Hungary the average of the years 1985-1987). Secondly, the year 1995 could also be selected as the base year for F-gases (HFCs, PFCs, SF6), which was used by Germany and Japan, for example.

The targets for individual countries (see table "Emission reductions of the first commitment period") depended primarily on their economic development. For the 15 states that were members of the European Union (EU-15) at the time the Kyoto Protocol was signed, a total reduction in emissions of 8 % was envisaged. In accordance with the principle of burden sharing, these 15 EU member states divided the average reduction target among themselves. Germany, for example, committed to a 21% reduction, the UK to a 12.5% reduction, France to stabilise at 1990 levels and Spain to limit its emissions growth to 15%.

The group "economies in transition" refers to the former socialist states or their successor states in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. These states either committed themselves, as in the case of Russia and Ukraine, not to exceed the emission level of the base years, or, as in the case of the Czech Republic and Romania, decided on a reduction of up to 8 %. Due to the economic collapse in 1990, these transition countries were still far from the emission levels at the start of the first commitment period. For emerging economies such as the People's Republic of China, India and Brazil, as well as for all developing countries, no limits were foreseen due to their low per capita emissions and in line with the provisions of the Framework Convention on Climate Change on "common but differentiated responsibilities" (see above). Malta and Cyprus were not listed in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol and were therefore also not obliged to make emission reductions.

The CO2 emissions of international aviation and international maritime shipping, which are growing twice as fast as those of other sectors and ranked seventh in a comparison of countries in 2005, even ahead of Germany, are not subject to any reduction commitments. The Protocol merely states that efforts should be continued within the framework of the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization, respectively.

The agreed reduction targets immediately drew criticism. Environmentalists in particular felt that the Protocol's reduction targets did not go far enough. Representatives of the business community, on the other hand, feared the high costs of implementing the Protocol.

The Kyoto International Conference Center in the northeastern district of Sakyō-ku, seen here from the outside, housed participating delegates for 11 days during the working sessions.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Kyoto Protocol?

A: The Kyoto Protocol is a plan created by the United Nations for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that tries to reduce the effects of climate change, such as global warming.

Q: What does the Kyoto Protocol ask countries to do?

A: The plan says that countries that adopt (follow) the Kyoto Protocol have to try to reduce how much carbon dioxide (and other "greenhouse gases" that pollute the atmosphere) they release into the air.

Q: Who created the Kyoto Protocol?

A: The Kyoto Protocol was created by the United Nations.

Q: Why was it created?

A: It was created in order to reduce the effects of climate change, such as global warming.

Q: What types of gases are included in this protocol?

A: The protocol includes carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that pollute the atmosphere.

Q: How do countries follow this protocol?

A: Countries must try to reduce how much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases they release into the air in order to follow this protocol.

Q: Is there any enforcement mechanism for following this protocol?

A: No, there is no enforcement mechanism for following this protocol; it relies on each country's voluntary commitment to reducing their emissions of greenhouse gases.

Search within the encyclopedia