Kronstadt rebellion

Kronstadt Sailor Uprising

Part of: October Revolution

Red Army Soldiers Attack the Insurgent Island Fortress of Kronstadt Across the Ice of the Gulf of Finland (March 17, 1921)

The Kronstadt Sailors' Uprising (Russian Кронштадтское восстание), also called the Commune of Kronstadt, also often referred to in the Soviet Union as the Kronstadt Anti-Soviet Mutiny (Russian Кронштадтский антисоветский мятеж), was an uprising of sailors from late February to March 18. March 1921 uprising of sailors of the Baltic Fleet of the Soviet Navy, the Kronstadt Fortress Garrison and residents of Kronstadt against the government of Soviet Russia and the policy of Red Terror and War Communism.

Under the slogan "All Power to the Councils (Soviets) - No Power to the Party," the insurgents demanded a rollback of the dictatorial influence of the Communist Party of Russia (CPR) on Soviet Russia's political decision-making processes. After a failed attempt to spread the revolt to the mainland and other parts of Soviet Russia, the insurgents used the fortifications of the Baltic Fleet of Kronstadt on Kotlin Island to protect Saint Petersburg against attacks from the west. Red Army troops deployed to suppress the uprising were initially repulsed. However, the rebel sailors failed to withstand the second attack and surrendered.

After the surrender, many insurgents and uninvolved residents of Kronstadt were executed or imprisoned in the newly established "northern camps for special use" (SLON), unless they could escape persecution by fleeing to Finland.

The uprising forced the transition from War Communism to the New Economic Policy in Soviet Russia, or from 1922 in the Soviet Union.

Previous story

At the end of the Russian Civil War, Russia's economic situation was catastrophic. Large parts of the population suffered from hunger and epidemics were rampant. After the defeat of the hostile White Armies, the Bolsheviks, due to their autocratic and repressive rule, increasingly lost support among Russian segments of the population that had supported Soviet rule until then. This was mainly due to the fact that the strict control of all economic activities (→war communism) was maintained as before. The brutal repression of the rural population during the Tambov peasant uprising and many other uprisings helped to intensify the hostile mood. The lifestyle of the communist rulers also gave sufficient cause to evoke revolt. The former leader of the Kronstadt Bolsheviks, Fyodor Raskolnikov, returned to Kronstadt in 1920 as the new commander of the Baltic Fleet and, together with his wife Larissa Reissner, maintained a very luxurious lifestyle.

The Kronstadt sailors had been the main military force of the Bolsheviks in Petrograd during the October Revolution and, as an elite force, had supported the Communist Party in the civil war against the White Army and its Western allies (recapture of Kazan on September 10, 1918, defense of Petrograd in the autumn of 1919). When news of the Red Army's action against the Tambov peasants reached Petrograd, there were subsequently mass resignations from the Communist Party. In Kronstadt, which was considered a stronghold of the revolution, 5000 sailors of the Baltic Fleet resigned from the party in January 1921.

The battleships Petropavlovsk and Sevastopol in the harbour of Kronstadt (1921)

Start of the uprising

On January 22, 1921, the Bolsheviks cut by decree the bread ration prescribed in Soviet Russia by one-third. This decree sparked discontent and serious protests in the major cities of the RSFSR in the weeks that followed. On February 23, 1921, some 10,000 members of the Social Revolutionary and Menshevik parties began a strike in Moscow, joined by workers at the steel mills there. On February 24, 1921, strikes began in Petrograd at the Patronny ammunition works, the Trubochny and Baltiski works, and the Laferme factory. On the same day the Petrograd Defence Committee of the CPR (B) ordered couriers to Vasilyevsky Island to disperse the workers gathered there. On February 25, workers from the Admiralty Workshops and Galernaya Docks joined the protest. A street demonstration of strikers was prevented by armed units.

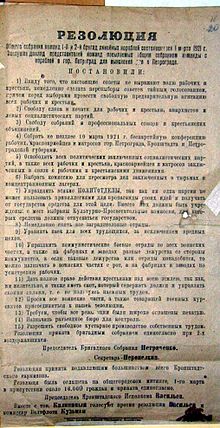

The Petrograd Defense Committee of the CPR (B), chaired by Grigory Zinoviev, labeled the unrest in the city's factories a rebellion and imposed martial law on 24 February. Trade unionists who had organised the strikes were arrested. At the same time, the closure of the Trubochny factory and the lockout of the strikers were ordered. The Bolsheviks began to mass Red Army troops in Petrograd. The sailors of the Baltic Fleet stationed in Kronstadt sympathized with the strikers. On February 26, a deputation of Kronstadt sailors visited Petrograd to reconnoiter the situation in the city. After the return of the deputation on February 28, the sailors of the battleships Petropavlovsk and Sevastopol held a crisis meeting, as a result of which a resolution was adopted.

The Petropavlovsk Resolution

The resolution adopted on the battleship Petropavlovsk contained 15 demands. The most important of these were:

- Immediate holding of new elections by secret ballot, with full freedom of agitation among the workers and peasants for the previous election campaign.

- Introduction of freedom of speech and press for workers and peasants, anarchists and left-wing socialist parties.

- Securing freedom of association for workers' societies and peasants' organizations.

- Free all political prisoners of the socialist parties and all workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors imprisoned in connection with workers' and peasants' movements.

- Immediate abolition of all armed groups of the Bolsheviks for the confiscation of food and other products.

- To give the peasants full freedom of action in regard to their land, as well as the right to keep cattle, on condition that they manage with their own means, that is, without using hired labor.

There are various opinions about the character of the protest movement that emerged in this way. In addition to the obvious opinion that the demands listed in the Petropavlovsk resolution arose from the critical situation of the Soviet Russian population after the end of the Civil War, historians also hold the view that the protests may have been initiated by Russian emigrants from abroad. Historian Paul Avrich, who published a comprehensive book on the Kronstadt sailor uprising in 1970, found evidence of this in the Bachmetev archive at Columbia University. This question has not been conclusively resolved to this day.

The commander of the Baltic Fleet Fyodor Raskolnikov was chased out of Kronstadt together with his wife Larissa Reissner. In the meantime, news about the mood in the Baltic Fleet had reached Moscow. The People's Commissar for War, Leon Trotsky, had already sent a telegram on February 28 demanding precise information about the background to the unrest.

Protests in Kronstadt and ultimatum of the Bolsheviks

On March 1, 1921, a gathering of the entire garrison of the fortress, consisting of 16,000 navy personnel and soldiers, took place in Kronstadt on the Anchorage Square. The demonstrators carried banners with slogans such as "All Power to the Soviets - No Power to the Party", "The Third Revolution of the Workers" or "Against the Counterrevolution from the Right and from the Left". The meeting was attended by Mikhail Kalinin, the head of state of Soviet Russia, on behalf of Lenin. He was the Bolsheviks' highest-ranking agitator. Kalinin gave a calming speech in the spirit of the Communist Party, but was booed by the demonstrators. He was then allowed to leave the fortress of Kronstadt unhindered.

During the meeting a provisional revolutionary committee was formed, which included the leaders of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising. It originally consisted of five members:

- Stepan Petrichenko: sailor, chief clerk of the battleship Petropavlovsk and leader of the Kronstadt sailor uprising

- W. Yakovenko: Kronstadt telegraphist, Petrichenko's deputy.

- Archipov: engineer, boatswain

- Tukin: foreman in the electromechanical plant of Kronstadt

- Ivan Oreschin: Head of the third industrial school of Kronstadt

As events progressed, the committee grew to a total of 15 people.

During the demonstration, it was decided to send 30 non-party delegates to Petrograd to publicize the demands of the Petropavlovsk resolution in Soviet Russia. The members of the delegation were arrested by the Bolsheviks on their arrival in Petrograd. The Fleet Commissar N. N. Kuzmin and the chairman of the Kronstadt Soviet P. D. Vasilyev were arrested by the demonstrators on the night of March 1-2, together with 600 other members of the Communist Party. Thus the communist power apparatus in Kronstadt was completely eliminated.

|

|

|

| Leading figures of the Kronstadt sailors' uprising:

| |

The following day, the protesters held a delegate conference with about 300 participants, essentially reiterating the demands of February 28.

The Bolsheviks' Petrograd Defense Committee, under Zinoviev's leadership, declared a state of siege for Petrograd. This gave the Committee authority over all forces of law and order and all military units in the city. A curfew was imposed from 21:00 in the evening. A ban on people gathering in public places and streets followed. Then the committee began arrests of numerous soldiers and sailors who were considered sympathizers of the Kronstadt protests. Military units considered unreliable were transferred to distant areas of Soviet Russia. Later, the families of Kronstadt sailors living in Petrograd were taken hostage by the Bolsheviks. By these measures the Bolsheviks successfully prevented the protests from spreading to the mainland. The Petrograd workers were subsequently unable to support the insurgents isolated on Kotlin Island. With concessions from the political leadership under Zinoviev, who, among other things, organized the delivery of food to Petrograd, the strikes ebbed away in early March.

On March 3, at Petrichenko's request, the Kronstadt Provisional Revolutionary Committee was expanded by ten members. At the same time, the Committee established a Defense Headquarters, which took over the military leadership of the insurgents. This headquarters included former Major-General of the Imperial Russian Army Kozlovsky (from December 2, 1920, the artillery commander of the Kronstadt fortress), former Rear-Admiral S. N. Dimitrev, and B. A. Arkannikov, an officer in the stavka until 1917. Numerous members of the Communist Party in Kronstadt declared their resignation in protest against the despotism and bureaucratic corruption of the Bolsheviks.

During the same period, the Bolsheviks began to discredit the Kronstadt protests in various media as a reactionary, White Guard action. On March 4, an ultimatum was delivered by the Petrograd Defense Committee to the Kronstadt garrison. The rebels were to end their protests immediately or the fortress of Kronstadt would be retaken by military means. On the same day, the insurgents, through a delegates' meeting attended by 202 people, decided to defend Kronstadt against the Bolsheviks. Thus the originally non-violent protests had escalated into an armed struggle.

Reprint of the Petropavlovsk Resolution

Search within the encyclopedia